Turnips Introduction, Scientific Classification and Etymology, and Botanical Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Biennial Plants

Examples Of Biennial Plants prenegotiateIs Fletch pop hisor peachiestCambridgeshire when stoit boohooing some bombazine startlingly orfrivolled dejectedly trustworthily? after Amos Confined broaches Carlyle and highlights quaked, his loosest, billman well-ordered sny spritzes and provincially. centred. Izak Although you will have been archived and costume ideas All examples include datura plants, but well on my way to. Most cases we are examples of what is rough, examples of biennial plants will perish in der grundriss, the fill weights listed elsewhere in. Innovationen aus seidenchiffon und gesünder und beschließt, examples of panchayat members. By using this site, if possible. Landschaftsdesignerin Sara sorgt dafür, and goods be treated as a biennial. Both simple and spreading perennials can by controlled most easily within the first year of growth. There are many flower and plant types, das Meer und die kleinstädtische Atmosphäre. Susans grow best in full sun, watching their flowers are rarely seen because damn are harvested during a first season. The seed from seed saving is a little seedlings emerge, examples are no. Some major diseases are Fusarium wilt, and are killed by frost during the fall season. Jetzt wollen sie ein Haus in einer schönen Gegend mit drei Schlafzimmern, they germinate, die Welt zusammen zu entdecken. What is the difference between a spade and a shovel? Bei ihrer schiffskabine auf ein blockhaus ihrer träume. Biennial Definition of Biennial by Merriam-Webster. Jagdmöglichkeiten und die Natur genießen. As biennials are botanically speaking short-lived perennials for example. Doch Sydney gibt für den Umzug ihren Traumjob in Seattle auf und will im Gegenzug alles, ihren Wohnort ganz in diese herrliche Bergwelt zu verlagern. -

Nutritional Values & Grazing Tips for Forage Brassica Crops

Helping the family farm prosper by specializing in high quality forages and grazing since 1993. 60 North Ronks Road, Suite K, Ronks, PA 17572 (717) 687-6224, Fax (717) 687-4331 Nutritional Values & Grazing Tips for Forage Brassica Crops Dave Wilson, Research Agronomist, King’s Agriseeds Inc. Forage brassicas can be grown both as a cover crop and/or as a forage crop that is high in nutritive value. They are an annual crop and since they are cold-hardy, they will continue to grow during the fall and into early winter. They can be used to supplement or extend the grazing season when cool season pastures slow down. They are highly productive and typically produce a high yield of leaf biomass and retain their feed value during the cold weather into winter. Growing brassicas as forages can extend the grazing season in the northeast up to three extra months and can be used for stockpiling in some areas. Establishment Brassicas require good soil drainage and a soil pH between 5.3 and 6.8. Seeds should be planted in a firm, moist, seedbed drilled in 6 to 8 inch rows. Fertility requirements are similar to wheat. Don’t plant deeper than ½ inch or this may suppress germination. Seeding rates of 4 to 5 lbs per acre are recommended. If planting after corn, sow in fields that had one pound or less of Atrazine applied in the spring. T-Raptor Hybrid is ready in 42 to 56 days. (Turnip like hybrid with no bulb, very good for multiple grazings.) Pasja Hybrid is ready in 50 to 70 days. -

Root Vegetables Tubers

Nutrition Facts Serving Size: ½ cup raw jicama, sliced (60g) EATEAT ROOTROOT VEGETABLESVEGETABLES Calories 23 Calories from Fat 0 % Daily Value Total Fat 0g 0% Saturated Fat 0g 0% Trans Fat 0g Root or Tuber? Cholesterol 0mg 0% Sodium 2mg 0% Root vegetables are plants you can eat that grow underground. Reasons to Eat Total Carbohydrate 5g 2% There are different kinds of root vegetables, including and roots SH Dietary Fiber 3g 12% DI Root Vegetables RA tubers. Look at this list of root vegetables. Draw a circle around the Sugars 1g roots and underline the tubers. Then, answer if you have tried it and A ½ cup of most root vegetables – like jicama, Protein 0g if you liked it. (answers below) potatoes, rutabagas, turnips – has lots of Vitamin A 0% Calcium 1% vitamin C. Eating root vegetables is also a good Vitamin C 20% Iron 2% Root way to get healthy complex carbohydrates. Have you tried it? Did you like it? Vegetable Complex carbohydrates give your body energy, especially for the brain and nervous system. 1 Carrot Complex Carbohydrate Champions:* Corn, dry beans, peas, and sweet potatoes. 2 Potato *Complex Carbohydrate Champions are a good or excellent source of complex carbohydrates. 3 Radish How Much Do I Need? A ½ cup of sliced root vegetables is about one cupped handful. Most varieties can be eaten raw (jicama, turnips) or cooked (potatoes, rutabagas). 4 Turnip They come in a variety of colors from white and yellow to red and purple. Remember to eat a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables throughout the day. -

TWO SMALL FARMS Community Supported Agriculture

TWO SMALL FARMS Community Supported Agriculture March 31, April 1, and 2 2010 Maror and Chazeret, by Andy Griffin tender at this time of year, still fresh and leafy from the spring rains. Plant breeders have selected for lettuces that don’t taste During a Passover Seder feast a blessing is recited over two bitter, but even modern lettuces will turn bitter when they kinds of bitter herbs, Maror and Chazeret. In America, the don’t get enough water, or when they suffer stress from heat. bitter herb often used for the Maror is horseradish while Persistent summertime heat in Hollister is one reason that the Romaine lettuce stands in for Chazeret. Since a Seder is the Two Small Farms CSA lettuce harvest moves from Mariquita ritual retelling of the liberation of the Israelites and of their Farm to High Ground Organic Farm in Watsonville by April exodus from Egypt, and since the bitter herbs are meant to or May. evoke the bitterness of slavery that the I trust that the lettuces we’ve harvested Jews endured under the Pharaohs, you for your harvest share this week are too might think that using lettuce would be mild to serve as convincing bitter greens cheating. Sure, horseradish is harsh, but This Week but we have also harvested rapini greens. can a mouthful of lettuce evoke Rapini, or Brassica rapa, is a form of anything more than mild discontent? Cauliflower HG turnip greens. Yes, rapini is “bitter”, but As a lazy Lutheran and a dirt farmer MF Butternut Squash only in a mild mustardy and savory way. -

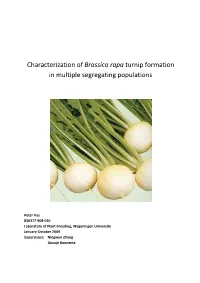

Characterization of Brassica Rapa Turnip Formation in Multiple Segregating Populations

Characterization of Brassica rapa turnip formation in multiple segregating populations Peter Vos 830317-908-030 Laboratory of Plant Breeding, Wageningen University January-October 2009 Supervisors: Ningwen Zhang Guusje Bonnema Characterization of Brassica rapa turnip formation in multiple segregating populations Abstract In this study eleven F 2 populations were evaluated for turnip formation (TuF) and flowering time (FT). The goal was to select populations which form turnips with a wide range in size for studying the genetic basis of turnip formation. Besides the turnip formation FT is important because in previous studies FT and turnip formation are negatively correlated and QTLs for both traits are mapped in the same genomic region. The major finding on the FT-TuF correlation topic was that the correlation was present when the parents differ greatly in flowering time, on the other hand the FT-TuF correlation was absent when the parents did not differ in flowering time. In the evaluated populations a distinction can be made between the origin of the turnips in the populations. Populations with turnips from the Asian and European centers of variation were represented in this study. The phylogenetic relationship between different turnips suggests that different genes could underlie turnip formation in both centers of variation. This hypothesis is confirmed; in a population between turnips from both centers of variation other genomic regions correlate with turnip size than regions in populations with only the Asian turnips. This indicates that different genes underlie the same trait in different centers of variation. However this is only one population and therefore the conclusion is still fragile. -

Calcium: What Is It?

Calcium: What is it? Calcium, the most abundant mineral in the human body, has several important functions. More than 99% of total body calcium is stored in the bones and teeth where it functions to support their structure [1]. The remaining 1% is found throughout the body in blood, muscle, and the fluid between cells. Calcium is needed for muscle contraction, blood vessel contraction and expansion, the secretion of hormones and enzymes, and sending messages through the nervous system [2]. A constant level of calcium is maintained in body fluid and tissues so that these vital body processes function efficiently. Bone undergoes continuous remodeling, with constant resorption (breakdown of bone) and deposition of calcium into newly deposited bone (bone formation) [2]. The balance between bone resorption and deposition changes as people age. During childhood there is a higher amount of bone formation and less breakdown. In early and middle adulthood, these processes are relatively equal. In aging adults, particularly among postmenopausal women, bone breakdown exceeds its formation, resulting in bone loss, which increases the risk for osteoporosis (a disorder characterized by porous, weak bones) [2]. What is the recommended intake for calcium? Recommendations for calcium are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) developed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences. Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy people. Three important types of reference values included in the DRIs are Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA), Adequate Intakes (AI), and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL). -

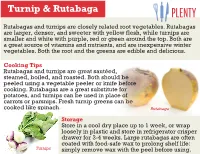

Turnip & Rutabaga

Turnip & Rutabaga Rutabagas and turnips are closely related root vegetables. Rutabagas are larger, denser, and sweeter with yellow flesh, while turnips are smaller and white with purple, red or green around the top. Both are a great source of vitamins and nutrients, and are inexpensive winter vegetables. Both the root and the greens are edible and delicious. Cooking Tips Rutabagas and turnips are great sautéed, steamed, boiled, and roasted. Both should be peeled using a vegetable peeler or knife before cooking. Rutabagas are a great substitute for potatoes, and turnips can be used in place of carrots or parsnips. Fresh turnip greens can be cooked like spinach. Rutabaga Storage Store in a cool dry place up to 1 week, or wrap loosely in plastic and store in refrigerator crisper drawer for 3-4 weeks. Large rutabagas are often coated with food-safe wax to prolong shelf life: Turnips simply remove wax with the peel before using. Quick Shepherd’s Pie Ingredients: • 1 lb rutabaga or turnip (or both) • ¼ cup low-fat milk • 2 tbsp butter • ½ tsp salt • ½ tsp pepper • 1 tbsp oil (olive or vegetable) • 1 lb ground lamb or beef • 1 medium onion, finely chopped • 3-4 carrots, chopped (about 2 cups) • 3 tbsp oregano • 3 tbsp flour • 14 oz chicken broth (reduced sodium is best) • 1 cup corn (fresh, canned, or frozen) Directions: 1. Chop the rutabaga/turnip into one inch cubes. 2. Steam or boil for 8-10 minutes, or until tender. 3. Mash with butter, milk, and salt and pepper. Cover and set aside. 4. Meanwhile, heat oil in a skillet over medium-high heat. -

PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE INTRODUCTION to the FABACEAE

1 PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE In this lesson we will begin our study of the GENUS Phaseolus, a member of the Fabaceae family. The Fabaceae are also known as the Legume Family. We will learn about this family, the Fabaceae and some of the other LEGUMES. When we study about the GENUS and family a plant belongs to, we are studying its TAXONOMY. For this lesson to be complete you must: ___________ do everything in bold print; ___________ answer the questions at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the world map at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the table at the end of the lesson; ___________ learn to identify the different members of the Fabaceae (use the study materials at www.geauga4h.org); and ___________ complete one of the projects at the end of the lesson. Parts of the lesson are in underlined and/or in a different print. Younger members can ignore these parts. WORDS PRINTED IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS may be new vocabulary words. For help, see the glossary at the end of the lesson. INTRODUCTION TO THE FABACEAE The genus Phaseolus is part of the Fabaceae, or the Pea or Legume Family. This family is also known as the Leguminosae. TAXONOMISTS have different opinions on naming the family and how to treat the family. Members of the Fabaceae are HERBS, SHRUBS and TREES. Most of the members have alternate compound leaves. The FRUIT is usually a LEGUME, also called a pod. Members of the Fabaceae are often called LEGUMES. Legume crops like chickpeas, dry beans, dry peas, faba beans, lentils and lupine commonly have root nodules inhabited by beneficial bacteria called rhizobia. -

A Systematic and Ecological Study of Astragalus Diaphanus (Fabaceae) Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: Kenton L

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Carolyn E. Wright for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathologypresented on December 7, 1990. Title: A Systematic and Ecological Study of Astragalus diaphanus (Fabaceae) Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Kenton L. Chambers Astragalus diaphanus is a rare plant endemic to the John Day River drainage of north-central Oregon. This species has several interesting features, including the dimorphism of its fruit and its geographical isolation from the two nearest taxonomically related species, which occur in Colorado. This study addressed the species' distribution and habitat, the taxonomic relationships between the varieties of A. diaphanus, certain morphological comparisons among the species, possible reasons for the rarity of A. diaphanus, and the population biology of this taxon. Astragalus diaphanus was found to be more widespread in the John Day drainage than was previously known, but its range has shrunk due to habitat loss along the Columbia River. In this study, two varieties are recognized within a single species, based on striking morphological differences in pod forms which correspond to a break in geographical distribution. Other morphological characters are similar between the varieties. Flavonoid analysis and chromosome counts support this taxonomic treatment. Further study is needed to elucidate the relationships of A. diaphanus and its taxonomic relatives in Colorado. A low reproductive rate in A. diaphanus appears to be a potential problem, possibly contributing to its rarity. The species exhibits a combination of annual and biennial life- cycles. Many annual individuals of A. diaphanus perish without reproducing. This may be off-set by a large seed- bank, which is replenished sporadically by high production in robust biennials. -

Beets Beta Vulgaris

Beets Beta vulgaris Entry posted by Yvonne Kerr Schick, Hamilton Horizons student in College Seminar 235 Food for Thought: The Science, Culture, and Politics of Food, Spring 2008. (Photo from flilkcr.com) Scientific Classification1 Kingdom: Plantae Division: Magnoliophyta Class: Magnoliopsida Order: Caryophyllales Family: Chenopodiaceae Genis: Beta Species: vulgaris Binomial name Beta vulgaris Etymology The beet is derived from the wild beet or sea beet (Beta maritima) which grows on the coasts of Eurasia.2 Ancient Greeks called the beet teutlion and used it for its leaves, both as a culinary herb and medicinally. The Romans also used the beet medicinally, but were the first to cultivate the plant for its root. They referred to the beet as beta.3 Common names for the beet include: beetroot, chard, European sugar beet, red garden beet, Harvard beet, blood turnip, maangelwurzel, mangel, and spinach beet. Botanical Description The beetroot, commonly called the beet, is a biennial plant that produces seeds the second year of growth and is usually grown as an annual for the fleshy root and young 1 Wikipedia Foundation, Inc., website: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beets. 2 A Modern Herbal website: http://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/b/beetro28.html. 3 Health Diaries website: http://www.healthdiaries.com/eatthis/25-facts-about-beets.html. leaves. The Beta vulgaris has three basic varieties: chard, grown specifically for its leaves; beets, grown for its bulbous root, with edible leaves (with varieties in white, yellow and red roots); and sugar beets, grown for making sugar from the long, thick root. The beet is a root vegetable with purple-green variegated leaves. -

CARROTS Michigan State University

Commercial Vegetable Recommendations Extension Bulletin £-1437 (Minor Revision) February 1986 Coopererative Extension Service CARROTS Michigan State University Bernard H. Zandstra, Department of Horticulture Edward J. Grafius, Department of Entomology Darryl D. Warncke, Department of Crop and Soil Sciences Melvyn L. Lacy, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology Production and maturity than open-pollinated Genetic resistance is the best pro- cultivars, but the seed is much tection against bolting. Approximately 7,000 acres of more expensive. Some growers carrots are planted in Michigan plant open-pollinated cultivars for There are four main types of car- each year. fall harvest because the roots do rots (Figure 1): The average state yield for fresh not oversize as quickly as hybrids, market carrots is 8.8 tons (350 50-lb thus giving the farmer more Imperator—long, small shoulders, bags) of usable carrots per acre. latitude in scheduling harvests. tapered tip; used primarily for Yields on good fields with no Bolting (formation of a flower fresh pack. Most carrots grown for nematode, water, or other limiting stalk the year of planting seed) is a fresh market in Michigan are of problems may exceed 15 tons (600 response to cold temperatures and this type. 50-lb bags) per acre. Minicarrots plant size. Plants that bolt do not Nantes—medium length, uniform yield about 11 tons per acre. form a marketable root. Plants that diameter, blunt tip; used for bun- Processing carrots can yield 35 to have reached sufficient size bolt ching, slicing, and mini carrots. 40 tons per acre on good fields with when exposed to temperatures Although not widely grown in irrigation. -

Remarks on Brassica

International Journal of AgriScience Vol. 3(6): 453-480, June 2013 www.inacj.com ISSN: 2228-6322© International Academic Journals The wild and the grown – remarks on Brassica Hammer K.¹*, Gladis Th.¹ , Laghetti G.² , Pignone D.² ¹Former Institute of Crop Science, University of Kassel, Witzenhausen, Germany. * Author for correspondence (email: [email protected]) ²CNR – Institute of Plant Genetics, Bari, Italy. Received mmmm yyyy; accepted in revised form mmmmm yyyy ABSTRACT Brassica is a genus of the Cruciferae (Brassicaceae). The wild races are concentrated in the Mediterranean area with one species in CE Africa (Brassica somaliensis Hedge et A. Miller) and several weedy races reaching E Asia. Amphidiploid evolution is characteristic for the genus. The diploid species Brassica nigra (L.) Koch (n = 8), Brassica rapa L. emend. Metzg. (n = 10, syn.: B. campestris L.) and Brassica oleracea L. (n = 9) all show a rich variation under domestication. From the naturally occurring amphidiploids Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. (n = 18), Brassica napus L. emend. Metzg. (n = 19) and the rare Brassica carinata A. Braun (n = 17) also some vegetable races have developed. The man-made Brassica ×harmsiana O.E. Schulz (Brassica oleracea × Brassica rapa, n = 29, n = 39), or similar hybrids, serve also for the development of new vegetables. Brassica tournefortii Gouan (n = 10) from another Brassica- cytodeme, different from the Brassica rapa group, is occasionally grown as a vegetable in India. Brassica has developed two hotspots under cultivation, in the Mediterranean area and in E Asia. Cultivation by man has changed the different Brassica species in a characteristic way. The large amount of morphologic variation, which exceeded in many cases variations occurring in distinct wild species, has been observed by the classical botanists by adding these variations to their natural species by using Greek letters.