Characterization of Brassica Rapa Turnip Formation in Multiple Segregating Populations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutritional Values & Grazing Tips for Forage Brassica Crops

Helping the family farm prosper by specializing in high quality forages and grazing since 1993. 60 North Ronks Road, Suite K, Ronks, PA 17572 (717) 687-6224, Fax (717) 687-4331 Nutritional Values & Grazing Tips for Forage Brassica Crops Dave Wilson, Research Agronomist, King’s Agriseeds Inc. Forage brassicas can be grown both as a cover crop and/or as a forage crop that is high in nutritive value. They are an annual crop and since they are cold-hardy, they will continue to grow during the fall and into early winter. They can be used to supplement or extend the grazing season when cool season pastures slow down. They are highly productive and typically produce a high yield of leaf biomass and retain their feed value during the cold weather into winter. Growing brassicas as forages can extend the grazing season in the northeast up to three extra months and can be used for stockpiling in some areas. Establishment Brassicas require good soil drainage and a soil pH between 5.3 and 6.8. Seeds should be planted in a firm, moist, seedbed drilled in 6 to 8 inch rows. Fertility requirements are similar to wheat. Don’t plant deeper than ½ inch or this may suppress germination. Seeding rates of 4 to 5 lbs per acre are recommended. If planting after corn, sow in fields that had one pound or less of Atrazine applied in the spring. T-Raptor Hybrid is ready in 42 to 56 days. (Turnip like hybrid with no bulb, very good for multiple grazings.) Pasja Hybrid is ready in 50 to 70 days. -

Root Vegetables Tubers

Nutrition Facts Serving Size: ½ cup raw jicama, sliced (60g) EATEAT ROOTROOT VEGETABLESVEGETABLES Calories 23 Calories from Fat 0 % Daily Value Total Fat 0g 0% Saturated Fat 0g 0% Trans Fat 0g Root or Tuber? Cholesterol 0mg 0% Sodium 2mg 0% Root vegetables are plants you can eat that grow underground. Reasons to Eat Total Carbohydrate 5g 2% There are different kinds of root vegetables, including and roots SH Dietary Fiber 3g 12% DI Root Vegetables RA tubers. Look at this list of root vegetables. Draw a circle around the Sugars 1g roots and underline the tubers. Then, answer if you have tried it and A ½ cup of most root vegetables – like jicama, Protein 0g if you liked it. (answers below) potatoes, rutabagas, turnips – has lots of Vitamin A 0% Calcium 1% vitamin C. Eating root vegetables is also a good Vitamin C 20% Iron 2% Root way to get healthy complex carbohydrates. Have you tried it? Did you like it? Vegetable Complex carbohydrates give your body energy, especially for the brain and nervous system. 1 Carrot Complex Carbohydrate Champions:* Corn, dry beans, peas, and sweet potatoes. 2 Potato *Complex Carbohydrate Champions are a good or excellent source of complex carbohydrates. 3 Radish How Much Do I Need? A ½ cup of sliced root vegetables is about one cupped handful. Most varieties can be eaten raw (jicama, turnips) or cooked (potatoes, rutabagas). 4 Turnip They come in a variety of colors from white and yellow to red and purple. Remember to eat a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables throughout the day. -

TWO SMALL FARMS Community Supported Agriculture

TWO SMALL FARMS Community Supported Agriculture March 31, April 1, and 2 2010 Maror and Chazeret, by Andy Griffin tender at this time of year, still fresh and leafy from the spring rains. Plant breeders have selected for lettuces that don’t taste During a Passover Seder feast a blessing is recited over two bitter, but even modern lettuces will turn bitter when they kinds of bitter herbs, Maror and Chazeret. In America, the don’t get enough water, or when they suffer stress from heat. bitter herb often used for the Maror is horseradish while Persistent summertime heat in Hollister is one reason that the Romaine lettuce stands in for Chazeret. Since a Seder is the Two Small Farms CSA lettuce harvest moves from Mariquita ritual retelling of the liberation of the Israelites and of their Farm to High Ground Organic Farm in Watsonville by April exodus from Egypt, and since the bitter herbs are meant to or May. evoke the bitterness of slavery that the I trust that the lettuces we’ve harvested Jews endured under the Pharaohs, you for your harvest share this week are too might think that using lettuce would be mild to serve as convincing bitter greens cheating. Sure, horseradish is harsh, but This Week but we have also harvested rapini greens. can a mouthful of lettuce evoke Rapini, or Brassica rapa, is a form of anything more than mild discontent? Cauliflower HG turnip greens. Yes, rapini is “bitter”, but As a lazy Lutheran and a dirt farmer MF Butternut Squash only in a mild mustardy and savory way. -

Calcium: What Is It?

Calcium: What is it? Calcium, the most abundant mineral in the human body, has several important functions. More than 99% of total body calcium is stored in the bones and teeth where it functions to support their structure [1]. The remaining 1% is found throughout the body in blood, muscle, and the fluid between cells. Calcium is needed for muscle contraction, blood vessel contraction and expansion, the secretion of hormones and enzymes, and sending messages through the nervous system [2]. A constant level of calcium is maintained in body fluid and tissues so that these vital body processes function efficiently. Bone undergoes continuous remodeling, with constant resorption (breakdown of bone) and deposition of calcium into newly deposited bone (bone formation) [2]. The balance between bone resorption and deposition changes as people age. During childhood there is a higher amount of bone formation and less breakdown. In early and middle adulthood, these processes are relatively equal. In aging adults, particularly among postmenopausal women, bone breakdown exceeds its formation, resulting in bone loss, which increases the risk for osteoporosis (a disorder characterized by porous, weak bones) [2]. What is the recommended intake for calcium? Recommendations for calcium are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) developed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences. Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy people. Three important types of reference values included in the DRIs are Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA), Adequate Intakes (AI), and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL). -

Turnip & Rutabaga

Turnip & Rutabaga Rutabagas and turnips are closely related root vegetables. Rutabagas are larger, denser, and sweeter with yellow flesh, while turnips are smaller and white with purple, red or green around the top. Both are a great source of vitamins and nutrients, and are inexpensive winter vegetables. Both the root and the greens are edible and delicious. Cooking Tips Rutabagas and turnips are great sautéed, steamed, boiled, and roasted. Both should be peeled using a vegetable peeler or knife before cooking. Rutabagas are a great substitute for potatoes, and turnips can be used in place of carrots or parsnips. Fresh turnip greens can be cooked like spinach. Rutabaga Storage Store in a cool dry place up to 1 week, or wrap loosely in plastic and store in refrigerator crisper drawer for 3-4 weeks. Large rutabagas are often coated with food-safe wax to prolong shelf life: Turnips simply remove wax with the peel before using. Quick Shepherd’s Pie Ingredients: • 1 lb rutabaga or turnip (or both) • ¼ cup low-fat milk • 2 tbsp butter • ½ tsp salt • ½ tsp pepper • 1 tbsp oil (olive or vegetable) • 1 lb ground lamb or beef • 1 medium onion, finely chopped • 3-4 carrots, chopped (about 2 cups) • 3 tbsp oregano • 3 tbsp flour • 14 oz chicken broth (reduced sodium is best) • 1 cup corn (fresh, canned, or frozen) Directions: 1. Chop the rutabaga/turnip into one inch cubes. 2. Steam or boil for 8-10 minutes, or until tender. 3. Mash with butter, milk, and salt and pepper. Cover and set aside. 4. Meanwhile, heat oil in a skillet over medium-high heat. -

Genetic Variation and Heritability Estimates of Quality Traits in Brassica Napus L

Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3208 (Paper) ISSN 2225-093X (Online) Vol.4, No.20, 2014 Genetic Variation and Heritability Estimates of Quality Traits in Brassica napus L. Sadia Shaukat 1, Raziuddin 1, Fahim Ullah Khan 1,2, *, Ibni Amin Khalil 1,3 1. Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, The University of Agriculture, Peshawar. 2.Barani Agricultural Research Station, Kohat. 3.Cereal Crops Research Institute, Pirsabak Nowshehra. *Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract To quantify genotypic variability and heritability among 8 Brassica napus genotypes were evaluated at New Developmental Research Farm, The University of Agriculture Peshawar during 2010-11. Analysis of variance revealed significant differences (P ≤0.01) among Brassica napus genotypes for all the character studied except for oil content. Mean values showed that maximum for oil content (52.0 %) for genotype CH-4, protein content (22.6 %) for genotype PGRI-7, glucosinolate content (85.4 umolg -1) for genotype CH-4 and erucic acid content (59.2 %) for genotype CH-3. One the other hand, minimum mean values for genotype PGRI-7, oil content (47.3 %) for genotype CH-1, protein content (18.4 %) for genotype CH-2, glucosinolate content (49.0 umolg -1) for genotype CH-2, erucic acid content (35.0 %) for genotype CH-2. In addition, high broad sense heritability estimates were observed for erucic acid content (0.90), glucosinolate content (0.53), protein content (0.45) and oil content (0.16). In conclusion, significant differences among Brassica napus genotypes indicated sufficient variability among the tested material to have an effective selection. -

Remarks on Brassica

International Journal of AgriScience Vol. 3(6): 453-480, June 2013 www.inacj.com ISSN: 2228-6322© International Academic Journals The wild and the grown – remarks on Brassica Hammer K.¹*, Gladis Th.¹ , Laghetti G.² , Pignone D.² ¹Former Institute of Crop Science, University of Kassel, Witzenhausen, Germany. * Author for correspondence (email: [email protected]) ²CNR – Institute of Plant Genetics, Bari, Italy. Received mmmm yyyy; accepted in revised form mmmmm yyyy ABSTRACT Brassica is a genus of the Cruciferae (Brassicaceae). The wild races are concentrated in the Mediterranean area with one species in CE Africa (Brassica somaliensis Hedge et A. Miller) and several weedy races reaching E Asia. Amphidiploid evolution is characteristic for the genus. The diploid species Brassica nigra (L.) Koch (n = 8), Brassica rapa L. emend. Metzg. (n = 10, syn.: B. campestris L.) and Brassica oleracea L. (n = 9) all show a rich variation under domestication. From the naturally occurring amphidiploids Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. (n = 18), Brassica napus L. emend. Metzg. (n = 19) and the rare Brassica carinata A. Braun (n = 17) also some vegetable races have developed. The man-made Brassica ×harmsiana O.E. Schulz (Brassica oleracea × Brassica rapa, n = 29, n = 39), or similar hybrids, serve also for the development of new vegetables. Brassica tournefortii Gouan (n = 10) from another Brassica- cytodeme, different from the Brassica rapa group, is occasionally grown as a vegetable in India. Brassica has developed two hotspots under cultivation, in the Mediterranean area and in E Asia. Cultivation by man has changed the different Brassica species in a characteristic way. The large amount of morphologic variation, which exceeded in many cases variations occurring in distinct wild species, has been observed by the classical botanists by adding these variations to their natural species by using Greek letters. -

Kohlrabi (Home Gardening Series)

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA6089 Home Gardening Series Kohlrabi Craig R. Andersen Environment Associate Professor and Light Extension Specialist Soil Vegetables Fertility pH Temperature Moisture – sunny – well-drained Culture– rich Planting– 6.0 to 7.0 – cool Spacing – keep moist Hardiness Fertilizer – transplant spring, direct Cultural Practices Kohlrabiseed – Brassicafall oleracea,– 2-4 gonglylodes x 24 inches Planting Time group – hardy annual – heavy feede r Capitulare de Villis of Charlemagne Plant kohlrabi in late winter or early spring before the heat of Kohlrabi was known to the summer and the stem gets woody. The Romans, and it was undoubtedly best production is in the fall when the recognized in the Middle Ages, as AD plants mature during cool conditions. shown in the SowCare seed 1/4 to 1/2 inch deep in the written in 749. row and cover. Thin seedlings to 2 to Today, cooked kohlrabi is widely used 5 inches apart. Transplant the surplus in continental Europe, but it is seedlings if more plants are needed in sparingly consumed in Britain and the row. other English-speaking countries. Kohlrabi (known as stem turnip) Plant in fertile soil, maintain Visit our web site at: is a hardy, cool-season vegetable adequate soil moisture and keep down https://www.uaex.uada.edu belonging to the cabbage family. It has a turnip-like appearance, with leaves weeds. Proper care allows kohlrabi to standing out like spokes. The edible achieve the rapid growth that results portion is an enlarged stem that in best quality. Treat kohlrabi as you University of Arkansas,grows United just Statesabove Department the groundline. -

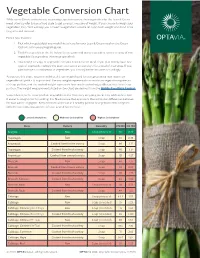

OPTAVIA® Vegetable Conversion Chart

Vegetable Conversion Chart While some Clients prefer to use measuring cups to measure their vegetables for the Lean & Green meal, others prefer to use a food scale to get an exact measure of weight. If you choose to weigh your vegetables, this chart will help you convert a vegetable’s volume (in cups) to its weight on a food scale (in grams and ounces). Here's how it works: 1. Pick which vegetable(s) you would like to have for your Lean & Green meal on the Green Options list in your program guide. 2. Find the vegetable in the list below for the gram and ounce equivalent to one serving of that vegetable (½ cup unless otherwise specified). 3. You need 3 servings of vegetables for your Lean & Green meal. If you plan to only have one type of vegetable, multiply the gram and ounce amount by 3 for a total of 3 servings. If you plan to have a combination of vegetables, you can adjust the amounts accordingly. As you use this chart, keep in mind that the raw weight listed is not representing how much raw vegetable will yield a ½ cup cooked. The raw weight represents how much raw vegetable equates to a ½ cup portion, and the cooked weight represents how much cooked vegetable equates to a ½ cup portion. The weight measurements listed on the chart are derived from the USDA’s FoodData Central. Some Clients prefer to weigh their vegetables in the form they are going to eat it in, while others find it easier to weigh prior to cooking. -

Crop Profile for Leafy Greens in North Carolina

Crop Profile for Leafy Greens in North Carolina Prepared: July, 2003 General Production Information ● North Carolina growers produced 243,000 cwt. of collards in 2001. North Carolina ranked third among the states in the production of collards in 2001, representing 14.5 percent of the U. S. production. A total of 2,800 acres of collards were planted and 2,700 acres of collards harvested in North Carolina in 2001. Growers in the state produced 90 cwt. of collards per acre in 2001, valued at $6,318,000. ● Growers in North Carolina produced 147,000 cwt. of turnip greens in 2001. North Carolina ranked third among the states in the production of turnip greens in 2001, representing 13.1 percent of the U. S. production. A total of 2,200 acres of turnip greens were planted and 2,100 acres of turnip greens harvested in North Carolina in 2001. Growers in the state produced 70 cwt. of turnip greens per acre in 2001, valued at $3,822,000. ● The production of mustard greens in North Carolina totaled 91,000 cwt. in 2001. North Carolina ranked fifth among the states in the production of mustard greens in 2001, representing 8.8 percent of the U. S. production. A total of 1,400 acres of mustard greens were planted and 1,300 acres of mustard greens harvested in North Carolina in 2001. Growers in the state produced 70 cwt. of turnip greens per acre in 2001, valued at $2,457,000. Production Regions Collards, kale, turnip greens and mustard greens are produced in all three of the regions of North Carolina, the Coastal Plain, Piedmont and Mountains. -

Brassica Spp.) – 151

II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) – 151 Chapter 3. Brassica crops (Brassica spp.) This chapter deals with the biology of Brassica species which comprise oilseed rape, turnip rape, mustards, cabbages and other oilseed crops. The chapter contains information for use during the risk/safety regulatory assessment of genetically engineered varieties intended to be grown in the environment (biosafety). It includes elements of taxonomy for a range of Brassica species, their centres of origin and distribution, reproductive biology, genetics, hybridisation and introgression, crop production, interactions with other organisms, pests and pathogens, breeding methods and biotechnological developments, and an annex on common pathogens and pests. The OECD gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Dr. R.K. Downey (Canada), the primary author, without whom this chapter could not have been written. The chapter was prepared by the OECD Working Group on the Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology, with Canada as the lead country. It updates and completes the original publication on the biology of Brassica napus issued in 1997, and was initially issued in December 2012. Data from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and FAOSTAT have been updated. SAFETY ASSESSMENT OF TRANSGENIC ORGANISMS: OECD CONSENSUS DOCUMENTS, VOLUME 5 © OECD 2016 152 – II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) Introduction The plants within the family Brassicaceae constitute one of the world’s most economically important plant groups. They range from noxious weeds to leaf and root vegetables to oilseed and condiment crops. The cole vegetables are perhaps the best known group. Indeed, the Brassica vegetables are a dietary staple in every part of the world with the possible exception of the tropics. -

Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley

Special Report 1064 January 2006 S 105 .E55 no. 1064 Jan 2006 Copy 2 Uutcros sing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley DOES NOT CIRCULATE Oregon State University Received on: 06-28-06 Oregon State I Extension Special report UNIVERSITY Service t1t41 I yt!r_.4.3 a Oregon State University Extension Service Special Report 1064 January 2006 Outcrossing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley James R. Myers Oregon State University Outcrossing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley James R. Myers Summary The oilseed mustards known as canola or rapeseed (Brassica napus and B. rapa) are the same species as some vegetable crucifers and are so closely related to others that interspecific and intergeneric crossing can occur. Intraspecific crosses (within the same species) readily occur among the following: • B. napus canola with rutabaga and Siberian kale • B. rapa canola with Chinese cabbage, Chinese mustard, pai-tsai, broccoli raab, and turnip Interspecific crosses (between different species) can occur among the following: • Occur readily: B. napus canola with Chinese cabbage, Chinese mustard, pai-tsai, broccoli raab, and turnip • Occur more rarely: B. napus or B. rapa canola with the B. oleracea cole crops (cabbage, kohlrabi, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, cauliflower, collards, and kale) Intergeneric crosses (between species of different genera) are possible with varying degrees of probability: • B. napus or B. rapa canola with wild and cultivated radish (Raphanus raphanis- trum and R.