To Read the Full Transcription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

References to Ffrench Mullen in the Allen Library

Dr. Kathleen Lynn Collection IE/AL/KL/1/7 25 June 1910 1 item; 2pp Empty envelope addressed to ‘Miss M. ffrench Mullen, 9 Belgrave Road, Rathmines, Dublin, Ireland.’ A list of names and numbers is written on the back of the envelope. IE/AL/KL/1/14 30 April 1916 1 item Handwritten last will and testament of Constance Markievicz. ‘I leave to my husband Casimir de Markievicz the sum of £100 pounds, to my stepson Stanislas de Markievicz the sum of £100 to Bessie Lynch who lived with me £25. Everything else I possess to my daughter, Medb Alys de Markievicz.’ Michael Mallin and Madeleine ffrench Mullen witnessed it. [Provenance: Given by Dr. Lynn, 10 September 1952]. IE/AL/KL/1/28 12 August 1916 1 item; 2pp Handwritten letter from Constance Markievicz, Holloway Jail to Madeleine ffrench Mullen. Constance Markievicz thanks her for the present and tells her ‘Mrs. Clarke is wonderful, with her bad health, its marvellous how she sticks it out at all. Give Kathleen and Emer my love and thank Emer for fags she sent me. I hope K is well; I heard that she was back from her holiday, but not going about much. I am all right again, gone up in weight and all the better for my enforced rest! …now goodbye much love to you and yours and my soldier girls.’ IE/AL/KL/1/30/1-2 7 November 1916 2 items Envelope and handwritten letter from Eva Gore Booth, 33 Fitzroy, Square, London to Dr. Lynn and Madeleine ffrench Mullen. -

Irish History Newsletter #5

Irish Women Rise LAOH Irish History Newsletter Nurses and Doctors of the Easter Rising LAOH ISSUE #5 !1 Margaret Keough Paul Horan, Assistant Professor of Nursing at Trinity College was studying his own family's participation in the Easter Rising when he stumbled on Margaret Keogh's story. He shares his research in an article in the Irish Mirror April 13, 2015. She was referred as the first martyr by Volunteer Commander Eamon Ceannt. She never made it to the history books. The British were in charge of the propaganda and wanted to hide the story of a uniformed nurse being shot by a British soldier. It is sad that the Irish did not tell the story but at the time they had their executed leaders stories to be told. Margaret Keough was a nurse working at the South Dublin Union who rushed to help the wounded at the time of her death on April 24,1916. She was shot by a British soldier as she was attending to the patients. Paul Horan is quoted in the article: "She would have been wearing her uniform so I find it very distasteful. I understand that people might get shot in the crossfire but the notion that a nurse in full uniform going to attend a casualty, was shot, that's cold-blooded murder." LAOH ISSUE #5 !2 Elizabeth O'Farrell Elizabeth O'Farrell remembered in an article for An Phoblacht that "she worked for Irish freedom from her sixteenth year " In 1906, she joined Inghindhe na hEireann and in 1914 joined the Cumann na mBan. -

View/Download

PART EIGHT OF TEN SPECIAL MAGAZINES IN PARTNERSHIP WITH 1916 AND COLLECTION Thursday 4 February 2016 www.independent.ie/1916 CONSTANCE MARKIEVICZ AND THE WOMEN OF 1916 + Nurse O’Farrell: airbrushed from history 4 February 2016 I Irish Independent mothers&babies 1 INTRODUCTION Contents Witness history 4 EQUALITY AGENDA Mary McAuliffe on the message for women in the Proclamation from GPO at the 6 AIRBRUSHED OUT Nurse Elizabeth O’Farrell’s role was cruelly excised from history heart of Rising 7 FEMALE FIGHTERS Joe O’Shea tells the stories of the women who saw 1916 action WITH its central role newlyweds getting their appeal to an international 8 ARISTOCRATIC REBEL in Easter Week, it was photos taken, the GPO audience, as well as Conor Mulvagh profiles the inevitable focus would has always been a seat of those closer to Dublin 1 enigmatic Constance Markievicz fall on the GPO for the “gathering, protest and who want a “window on Rising commemorations. celebration”, according to Dublin at the time” and its 9 ‘WORLD’S WILD REBELS’ And with the opening of McHugh. When it comes residents. Lucy Collins on Eva Gore- the GPO Witness History to its political past, the As part of the exhibition, Booth’s poem ‘Comrades’ exhibition, An Post hopes immersive, interactive visitors will get to see to immerse visitors in the centre does not set out to inside a middle-class 10 HEART OF THE MATER building’s 200-year past. interpret the events of the child’s bedroom in a Kim Bielenberg delves into the According to Anna time. -

1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL 2 Liberty • 1913 Lockout Special

October 2013 ISSN 0791-458X 1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL 2 Liberty • 1913 Lockout Special HE 1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL has been published to coincide with the SIPTU Highlights Biennial National Delegate Conference T which takes place in the Round Room, Mansion House in Dublin from Monday 7th October, 2013. 7 The Lockout Special is dedicated to those who gave their lives and 8-9 My granddad liberty during the historic labour struggle in Dublin one hundred years Jim Larkin ago and to the courageous workers and their families who endured Connolly still such hardship as they fought for the right to be members of a trade inspires An interview with Stella Larkin McConnon union. In this special edition of Liberty we reproduce many images, includ- James Connolly Heron ing original photographs depicting the determination of the 20,000 recalls the ideals of his locked out workers during those months from August 1913 to January great –grandfather 1914 when employers, supported by a brutal police force and the main- 10-11 stream media, sought to starve them and their families into submis- sion. The women of 1913 The horrific social conditions in Dublin at the time, which 13 Women’s role in the Lockout and contributed greatly to the anger of the city’s exploited general workers, Rosie Hackett in her own words are also recalled while similar confrontations between labour and The unfinished capital in other towns and cities across the country during the period business of 1913 are recounted. The significant role of women during the Lockout is examined while Fintan O’Toole on why 14 the battle with the Catholic Church over the controversial effort to send the issues at stake in the The divine mission of discontent the hungry children of hard pressed families to supporters in England Lockout are still alive is also revisited. -

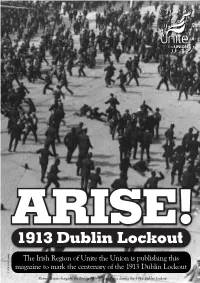

The Irish Region of Unite the Union Is Publishing This Magazine to Mark

5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 1 The Irish Region of Unite the Union is publishing this magazine to mark the centenary of the 1913 Dublin Lockout © RTÉ Stills Library Picture: Baton charge by the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the 1913 Dublin Lockout 5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 2 Page 2 June 2013 Larkininism and internationalism This is an edited version of a lecture delivered by Unite General Secretary Len McCluskey to a meeting organised by Unite with the support of the Dublin Council of Trade Unions and Dublin Community Television. The event took place in Dublin on May 29th 2013 A crowd awaits the arrival of the first food ship from England, 28 September 1913 (Irish Life magazine). Contents Page2: Len McCluskey – Larkinismandinternationalism Page7: Jimmy Kelly – 1913–2013:Forgingalliancesofthediscontented Page9: Theresa Moriarty – Womenattheheartofthestruggle Page11: Padraig Yeates – AveryBritishstrike 5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 3 June 2013 Page 3 It is a privilege for me to have this opportunity workers,andgovernmentsunableorunwillingto IamproudthatUniteisleadingbyexample.Weare to speak about a man – from my own city – bringaboutthereformpeoplesodesperatelyneed. committedtobuildinganewsenseofoptimismfor who I consider a personal hero. ourmovement,whetherthatisathomethroughour Acrosstheworld,multilateralinstitutionsandthe communitymembershipbringingtheunemployed Iwanttotouchonanumberofthemesrelatingto agreementsthatemanatefromthemarelittle -

History Rosie Hackett 1911 Census and 1916

Evidence and Enquiry: Using the 1901 and 1911 census forms in the History classroom, 2016 edition Examining the 1911 census record of Rosie Hackett Section One: Locating the census record. To find the census form for Rosanna Hackett in 1911. 1. Go to www.census.nationalarchives.ie . 2. Click on “Search the census records for Ireland 1901 and 1911”. 3. Choose the census year, 1911. 4. Write in the name Hackett on the surname line. 5. Write in Rosanna on the Forename line. 6. Click the name Dublin in the drop-down list on the county line. 7. Write in the name North Dock in the DED line. 8. Click search. 9. Click on the name Rosanna Hackett. 10. To see all of the personal information about her family, click on the box for the heading, “show all information”. 11. Below the typed family information, you can view the four original forms relating to her family - the household return (Form A), the enumerator's abstract (Form N), the house and building returns (Form B1), and the Out-Offices Return (Form B2). 12. If the number 2 appears underneath any of these forms, click on the number. It will open up the reverse side of the form. CSO 2016 E History Rosie Hackett in 1911 and 1916 2nd draft 1 Section Two: The 1911 census form of Rosanna Hackett The following is a transcript of the information on Rosanna Hackett on the 1911 census form, under the heading, “Residents of a house 3 in Abbey Street, Old (North Dock, Dublin)” Surname Christian Age Sex Relation to Religion Birthplace Occupation name head Head of Roman Caretaker in Gray Patrick 42 Male -

Irish Women Rise in 1916

Irish Women Rise in 1916 Women Active in the Easter Rising and their Garrison General Post Office City Hall Unknown Garrison Winifred Carney Brigid Brady Nano Aiken Brigid Carron Mrs. Connolly Eli's Aughney Nellie Ennis Brigid Davis Kathleen Barrett Nora Gavan Bessie Lynch Kitty Barrett Julia Grennan Dr. Kathleen Lynn Kitty Brown Mrs. Joe McGuinness Helena Molony Martha Brown Mary Mcloughlin Annie Norgrove Eileen Byrne Sorcha Mcmahon Emily Norgrove May Carron Florence Meade Mollie O'Reilly May Derham Carrie Mitchell Jennie Shanahan Emily Elliott Pauline Morkan M. Elliott Elizabeth O'Farrell St Stephens Green/Surgeons Ellen Ellis Molly O'Sullivan Chris Caffery M. Fagan Dolly O'Sullivan Countess deMarkievicz Kathleen Fleming Aine Ryan Mary Devereux Brigid Foley Min Ryan Madeleine French Mullen Katie Foley Phyllis Ryan Nellie Gifford Nora Foley Eilis niRiain Brigid Gough May Gahan Martha Walsh Rosie Hackett Patricia Hoey Kate Walsh Mary Hyland Sarah Kealy Mrs. Joe Walsh Maggie Joyce Martha Kealy Annie Kelly May Kelly Four Courts Lily Kempson K. Lane Mrs. Conlon Margaret Ryan Mrs. Lawless Anna Fay Kathleen Seery Catherine Liston Julie Grennan Margaret Skinnider Mary Liston Mrs. Hayes Brigid Lyons Kathleen Kenny GPO/St. Stephens Green Kathleen Maher Brigid Martin Mary McGloughlin G. Milner Rose McGuinness Hanna Sheehy Seffington Jenny Milner Phyllis Morkan Mary Moore Lily Murnane Bolands May Murray Mrs. Murphy Josephine Purgield Brigid Murtagh Mrs. Parker Courier Maire ni Shiublaigh B. Walsh Peg Cuddihy Lily O'Brennan Eileen Walsh Maria Perolz Nara Daly Distillery Marrowbone Lane Louisa O'Sullivan Katie Byrne Leslie Price Winnie Byrne Matilda Simpson May Byrne Lucy Smith Annie Cooney Josephine Spicer Eileen Cooney D. -

Women in the Irish Revolution

Women in the Irish Revolution Mary Smith Anyone who knows anything and socially from the devastating effects of about history knows also that famine fifty years earlier. It was a predom- great social upheavals are impos- inately rural and agricultural society with sible without the feminine fer- a poorly developed industrial infrastructure, ment. - Karl Marx1 apart from Belfast, where the success of the ship-building industry in particular under- In the introduction to her book Un- pinned loyalty to union with Britain. In manageable Revolutionaries; women and the south, the emerging Catholic middle Irish nationalism, the historian Dr Margaret and upper classes were socially conservative, Ward states that: ‘...writing women into his- heavily influenced by, and reliant upon, the tory does not mean simply tagging them church3. They (correctly) perceived them- onto what we already know; rather, it forces selves as being ‘held back’ by the union with us to re-examine what is currently accepted, Britain and aspired to Home Rule. The Irish so that a whole people will eventually come Parliamentary Party or Home Rule Party into focus...’2 This article is an attempt to was the expression of their nationalist as- sharpen the focus on events relating to the pirations. Rising in Dublin 1916, by recounting the role played by women. What it seeks to do specifically is: Life for working class men and women was harsh. Poverty and emigration were rife; • briefly outline the role played by Dublin city had reputedly the worst slums women in the Easter Rising itself and in Europe. The minimum working age was the political events and movements eight years old. -

7 Women of the Labour Movement

Seven Women of the Labour Movement 1916 Written and researched by Sinéad McCoole. List of women of the Irish Citizen Army: Garrison of the General Post Office: City Hall Garrison: Winifred Carney; Dr Kathleen Lynn, Helena Molony, Garrison of St Stephen’s Jennie Shanahan, Green/College of Surgeons: Miss Connolly (Mrs Barrett), Bridget Brady, Countess de Markievicz, Mollie O’Reilly (Mrs Corcoran), Mary Devereux (Mrs Allen), Bridget Davis (Mrs Duffy), Nellie Gifford (Mrs Donnelly), Annie Norgrove (Mrs Grange), Margaret Ryan (Mrs Dunne), Emily Norgrove, (Mrs Hanratty), Bridget Gough; Bessie Lynch (Mrs Kelly); Madeleine ffrench Mullen, Rosie Hackett, Imperial Hotel Garrison: Mrs Joyce, Chris Caffery (Mrs Keeley), Martha Walsh (Mrs Murphy). Annie Kelly, Mary Hyland (Mrs Kelly), Lily Kempson, Mrs Norgrove, Kathleen Seerey (Mrs Redmond), [Source: RM Fox, The History of the Irish Citizen Army, James Duffy Margaret Skinnider; & Co Ltd, 1944.] In 1900, as the new century dawned, large numbers of women were beginning to take part in active politics. They came from diverse backgrounds and united in common causes such as the rights of workers. These women were activists and workers at a time when it was both ‘unladylike’ and ‘disreputable’ for them to take part in politics. They suffered poverty, imprisonment, ill-heath and, in some cases, premature death because of their stance. In 1911 the Irish Women Workers’ Union was established. James Connolly wrote: “The militant women who without abandoning their fidelity to duty, are yet teaching their sisters to assert their rights, are re-establishing a sane and perfect balance that makes more possible a well ordered Irish nation’’ Inspired by the leadership of James Larkin and James Connolly strikes became more frequent until 1913 when over 20,000 workers took part in what became known as the Lock Out. -

1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL 2 Liberty • 1913 Lockout Special

October 2013 ISSN 0791-458X 1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL 2 Liberty • 1913 Lockout Special HE 1913 LOCKOUT SPECIAL has been published to coincide with the SIPTU Highlights Biennial National Delegate Conference T which takes place in the Round Room, Mansion House in Dublin from Monday 7th October, 2013. 7 The Lockout Special is dedicated to those who gave their lives and 8-9 My granddad liberty during the historic labour struggle in Dublin one hundred years Jim Larkin ago and to the courageous workers and their families who endured Connolly still such hardship as they fought for the right to be members of a trade inspires An interview with Stella Larkin McConnon union. In this special edition of Liberty we reproduce many images, includ- James Connolly Heron ing original photographs depicting the determination of the 20,000 recalls the ideals of his locked out workers during those months from August 1913 to January great –grandfather 1914 when employers, supported by a brutal police force and the main- 10-11 stream media, sought to starve them and their families into submis- sion. The women of 1913 The horrific social conditions in Dublin at the time, which 13 Women’s role in the Lockout and contributed greatly to the anger of the city’s exploited general workers, Rosie Hackett in her own words are also recalled while similar confrontations between labour and The unfinished capital in other towns and cities across the country during the period business of 1913 are recounted. The significant role of women during the Lockout is examined while Fintan O’Toole on why 14 the battle with the Catholic Church over the controversial effort to send the issues at stake in the The divine mission of discontent the hungry children of hard pressed families to supporters in England Lockout are still alive is also revisited. -

Women & the 1916 Rising

WOMEN & THE 1916 RISING An educational resource Niamh Murray, 2016. Preface This pack is intended to provide some basic information on the women who participated in the 1916 Easter Rising. Each profile contains brief information about the woman’s role in the Rising and what happened to her in the aftermath. Included in each profile is an interesting fact about each woman, not related to the Rising, which may inspire further research. Women and the Rising: Background Roughly 270-300 women took part in the events of Easter Week. The women who participated in the Rising were either members of The Irish Citizen Army or Cumann na mBan. During the Rising, women were represented in all garrisons, except Boland’s Mills. Its Commandant, Eamon de Valera, refused to allow women have any role in events. Margaretta Keogh, a nurse, was the only woman to be killed during the Rising. She was shot accidentally when she went to help an injured man near the South Dublin Union garrison. The Irish Citizen Army James Connolly, leader of the Irish Citizen Army was a firm supporter of women’s suffrage and believed women should be treated equally, hence the women in the ICA played a larger role in the Rising than those in Cumann na mBan. Some of them were armed and two of them held rank positions (Markievicz as Lieutenant & Lynn as Captain). The majority of the ICA women were stationed in St. Stephen’s Green/Royal College of Surgeons and City Hall during Easter Week. Cumann na mBan Women were not allowed join the Irish Volunteers, so a group of women who wanted to take an active role in the nationalist struggle, decided to set up their own organisation. -

An Introduction to the Bureau of Military History 1913 - 1921

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE BUREAU OF MIliTARY HISTORY 1913 - 1921 by j ENNIPIlR D OYLE F RAl\'CES CUI RKE EfBHUS COi\'j\'iiUGHTOl\' OR;\'A SOMERVIllE Military Archives Cathal Brugha Barracks Rathm.ines Dublin 6 COller: Burial <if TholllosAshc) GlnsllflJill ) 30 Scprcl/IIJcr 1917. (C D 227/35/ 3) Copyright © Military Archives, 2002 All fights reserved. No part of this publicarioll lllay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system , or transmitted in any fo rlll or by any means, electronic. mechanical , photocopying, recording or otherwise "'''Iehom prior permission from the pllblishers. An Introduction to The Bureau of Military History 1913 - 1921 FOREWORD The origins of rhL' collecti on of archi val material described as the Bureau of Military History 19'13- J 921 are expbined in SO Il'lt:! d l.:., taii in the first chaptL' r of this publica tion. As the ride implies. this bookkt has bc~n produced to act as an inrroduction to the coll ec tion. Hopefull y it will SL'n-c as such and will assist ;lIld encourage student'i of this period of our hi story. As a result of vario lls initiatives the Governlllent decided to re lease the coll ection to the Miliwry Archivt's. After all , rh e impcms fo r the project came frOI11 within the D efence Forces in rhe forties and Illllch m:uaial of a complementary 1lJ.n1re such as 'The Collins papers' and Deparnnenral files art' in the keeping of Mili tary Archives. This bookJet is intended to give readers a fla vour of dl C material donated ro the Bureau by associates :l11d members of various political, social :md cultural groups and other individuals im·olvt'd in dll' ('vems of the timt'.