Hawk Nest Site Assessment (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knowledge Document on the Impact of Priority Wetland Weeds

Knowledge document on the impact of priority wetland weeds Step 2 – Impacts of priority wetland weeds Client Report for DELWP, Integrated Water and Catchments Division Arthur Ryah Institute for Environmental Research Acknowledgements This project has been undertaken with funding from Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) Water and Catchments Group. Pam Clunie (Arthur Rylah Institute; DELWP) and Doug Frood (Pathways Bushland & Environment) provided valuable assistance in determining the scope of the project and filtering the wetland weed list. Phil Papas and Di Crowther (Arthur Rylah Institute; DELWP) are thanked for reviewing the draft. Author Weiss, J. and Dugdale, T. 2017. Knowledge document of the impact of priority wetland weeds: Step 2 – Impacts of priority wetland weeds. Report prepared for Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) Water and Catchments Group by Agriculture Victoria. Photo credit Sagittaria platyphylla, Sagittaria, Delta Arrowhead (Anonymous, Agriculture Victoria, DEDJTR) © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-1-76047-452-2 (print) ISBN 978-1-76047-453-9 (pdf) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

(Cruciferae) – Mustard Family

BRASSICACEAE (CRUCIFERAE) – MUSTARD FAMILY Plant: herbs mostly, annual to perennial, sometimes shrubs; sap sometimes peppery Stem: Root: Leaves: mostly simple but sometimes pinnately divided; alternate, rarely opposite or whorled; no stipules Flowers: mostly perfect, mostly regular (actinomorphic); 4 sepals, 4 petals often forming a cross; 6 stamens with usually 2 outer ones shorter than the inner 4; ovary superior, mostly 2 fused carpels, 1 to many ovules, 1 pistil Fruit: seed pods, often used in classification, many are slender and long (Silique), some broad (Silicle) – see morphology slide Other: a large family, many garden plants such as turnip, radish, and cabbage, also some spices; often termed the Cruciferae family; Dicotyledons Group Genera: 350+ genera; 40+ locally WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive Flower Morphology in the Brassicaceae (Mustard Family) - flower with 4 sepals, 4 petals (often like a cross, sometimes split or lobed), commonly small, often white or yellow, distinctive fruiting structures often important for ID 2 types of fruiting pods: in addition, fruits may be circular, flattened or angled in cross-section Silicle - (usually <2.5x long as wide), 2-valved with septum (replum) Silique - (usually >2.5x long as wide), 2- valved with septum (replum) Flowers, Many Genera BRASSICACEAE (CRUCIFERAE) – MUSTARD FAMILY Sanddune [Western] Wallflower; Erysimum capitatum (Douglas ex Hook.) Greene var. capitatum Wormseed Wallflower [Mustard]; Erysimum cheiranthoides L. (Introduced) Spreading Wallflower [Treacle Mustard]; Erysimum repandum L. (Introduced) Dame’s Rocket [Dame’s Violet]; Hesperis matronalis L. (Introduced) Purple [Violet] Rocket; Iodanthus pinnatifidus (Michx.) Steud. Michaux's Gladecress; Leavenworthia uniflora (Michx.) Britton [Cow; Field] Cress [Peppergrass]; Lepidium campestre L.) Ait. -

Laurentian Mixed Forest Province, Cliff/Talus System Summary

CT Cliff and Talus System photo by M.D. Lee MN DNR Lake County, MN General Description Communities in the Cliff/Talus (CT) System are present on cliffs or talus slopes on steep- sided knobs, in river gorges, along lakeshores, and in other settings with sheer bedrock exposures. Often, cliffs and talus slopes are associated with one another because talus slopes are composed of rock fractured either from cliffs or from exposed bedrock on steep hillsides. The vegetation of CT communities is generally open. Lichens and moss- es are the dominant life forms, with vascular plants sparse or patchy because of scarcity of soil. In this classification, cliff communities are grouped by moisture and light regimes and by bedrock type, which are the major determinants of species composition. Cliff habitats range from warm and dry to cool and wet depending on cliff aspect, proximity to streams or lake shores, and presence of groundwater seepage on the cliff face. In the Laurentian Mixed Forest (LMF) Province, cliffs are formed most commonly of igneous bedrock, although cliffs on metamorphic rock are also common. Talus communities are classified according to amount of woody plant cover and moisture regime. In the LMF Province, CT communities are restricted mostly to the North Shore High- lands and Border Lakes subsections in NSU, where Precambrian bedrock is frequently at or just below the surface and topography is often rugged. Scattered cliffs are present in WSU and are likely in the Laurentian Uplands Subsection in NSU and the Littlefork- Vermilion Uplands Subsection in Northern Minnesota & Ontario Peatlands MOP, primar- ily along lakes and streams where water has exposed the underlying bedrock. -

Circumneutral Mixed Shrub Wetland System

Circumneutral Mixed Shrub Wetland System: Palustrine Subsystem: Shrubland PA Ecological Group(s): Basin Wetland Global Rank: G4G5 State Rank: S3 General Description This shrub-dominated wetland community occurs in a variety of palustrine settings, including the upland edge of marshes, at the wetter edge of red maple wetlands, in small upland depressions, stream floodplains, and at the base of slopes. The community may represent a successional stage between abandoned agricultural land and a forest community. The substrate is generally very poorly drained shallow peat or mineral soil with a thin organic layer. These wetlands are generally seasonally flooded and may remain saturated for much of the growing season. Nutrient enrichment is generally the result of discharge from groundwater or inflow from the surrounding watershed. The pH of these systems is broadly circumneutral to somewhat calcareous, and calciphiles may be present. Many of these wetlands were or currently are influenced by beaver activity or other impoundments. Grazing (past and present) and previous land use history (e.g., farming) may also be a factor. Community size ranges from small inclusions to extensive acreage. The community is characterized by a substantial tall-shrub layer that may be dominated by a single shrub species or a patchwork of mixed shrubs. Shrub species typically found in this community include: smooth alder (Alnus serrulata), speckled alder (A. incana ssp. rugosa), ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), willows (Salix spp.), American elder (Sambucus canadensis), dogwoodc (Cornus spp.), water- willow (Decodon verticillatus), buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), viburnum (Viburnum spp.), meadow-sweet (Spiraea spp.), and swamp rose (Rosa palustris). Scattered seedling/sapling sized trees may be present such as red maple (Acer rubrum). -

Links Between Genetic Groups, Indole Alkaloid Profiles and Ecology Within the Grass-Parasitic Claviceps Purpurea Species Complex

Toxins 2015, 7, 1431-1456; doi:10.3390/toxins7051431 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article Links between Genetic Groups, Indole Alkaloid Profiles and Ecology within the Grass-Parasitic Claviceps purpurea Species Complex Mariell Negård 1,2, Silvio Uhlig 1,3, Håvard Kauserud 2, Tom Andersen 2, Klaus Høiland 2 and Trude Vrålstad 1,2,* 1 Norwegian Veterinary Institute, P.O. Box 750 Sentrum, 0106 Oslo, Norway; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.N.); [email protected] (S.U.) 2 Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1066 Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway; E-Mails: [email protected] (H.K.); [email protected] (T.A.); [email protected] (K.H.) 3 Department of the Chemical and Biological Working Environment, National Institute of Occupational Health, P.O. Box 8149 Dep, 0033 Oslo, Norway * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-2321-6247. Academic Editor: Christopher L. Schardl Received: 3 January 2015 / Accepted: 22 April 2015 / Published: 28 April 2015 Abstract: The grass parasitic fungus Claviceps purpurea sensu lato produces sclerotia with toxic indole alkaloids. It constitutes several genetic groups with divergent habitat preferences that recently were delimited into separate proposed species. We aimed to 1) analyze genetic variation of C. purpurea sensu lato in Norway, 2) characterize the associated indole alkaloid profiles, and 3) explore relationships between genetics, alkaloid chemistry and ecology. Approximately 600 sclerotia from 14 different grass species were subjected to various analyses including DNA sequencing and HPLC-MS. -

Morphologically and Physiologically Diverse Fruits of Two Lepidium

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.23.887026; this version posted December 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Morphologically and physiologically diverse fruits of two Lepidium species differ 2 in allocation of glucosinolates into immature and mature seed and pericarp 3 4 Said Mohammed1,#a¶, Samik Bhattacharya1¶*, Matthias A. Gesing2¶, Katharina Klupsch3, 5 Günter Theißen3, Klaus Mummenhoff1&, Caroline Müller2& 6 1 Department of Biology, Botany, University of Osnabrück, Barbarastraße 11, D-49076 7 Osnabrück, Germany 8 2 Faculty of Biology, Department of Chemical Ecology, Bielefeld University, 9 Universitätsstraße 25, D-33615 Bielefeld, Germany 10 3 Matthias Schleiden Institute / Genetics, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, 11 Philosophenweg 12, 07743, Jena, Germany 12 #a Current address: Department of Biology, Debre Birhan University, Ethiopia 13 14 * Corresponding author 15 E-mail: [email protected] (SB) 16 17 ¶These authors contributed equally to this work. 18 19 Short title: Glucosinolate allocation in Lepidium seed and pericarp 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.23.887026; this version posted December 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 20 Abstract 21 The morphology and physiology of diaspores play crucial roles in determining the fate of 22 seeds in unpredictable habitats. -

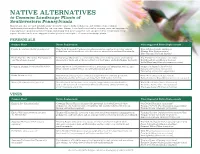

Audubon Native Alternatives Flyer V5

NATIVE ALTERNATIVES to Common Landscape Plants of Southwestern Pennsylvania Many plants that are used in landscaping offer little value to birds, pollinators, and wildlife. Some common landscaping plants such as English Ivy can even cause damage to our local ecosystem by escaping yards and aggressively replacing native plants in natural settings. Gardening with native plants is easy and protects the biodiversity of our region. Read below for some suggested native plants to use in place of common landscape plants. PERENNIALS Common Plant Native Replacement Other Suggested Native Replacements Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) 1 New York Ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis) is a nectar source for various Blue Lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica) pollinators and its seeds are a food source for many birds and small mammals. Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) Blue Vervain (Verbena haststa) Exotic Bamboo (Bambusa, Phyllostschys, Indiangrass (Sorghastrum nutans) provides cover, nesting areas, and nesting Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) and Pseudosasa species) 2 material for birds and is the larval host for the Pepper and Salt Skipper Butterfly. Bottlebrush Grass (Elymus hystrix) Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) Common Daylily (Hermerocallis fulva) 3 Butterfly Weed (Asclepsias tuberosa) is a host plant for Monarchs, Queen, and Ox Eye (Heliopsis helianthoides) Gray Hairstreak butterflies, and attracts hummingbirds. Canada Lily (Lilium canadense) Turk’s Cap Lily (Lilium superbum) Hosta (Hosta species) Blue Cohosh (Caulophyllum thalictroides) provides nectar and pollen for Coral Bells (Heuchera americana) pollinators and the berries are an important fruit source for birds. False Solomon’s Seal (Maianthemum racemosum) Mums (Chrysanthemum species) New England Aster (Aster novae-angliae) supports bees and butterflies White Wood Aster (Aster divaricatus) and is the larval host for the Pearl Crescent Butterfly. -

Phalaris Arundinacea

Phalaris arundinacea Phalaris arundinacea INTRODUCTORY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE EFFECTS AND MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDIX: FIRE REGIME TABLE REFERENCES INTRODUCTORY AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY SYNONYMS LIFE FORM Photo by John M. Randall, The Nature Conservancy, Bugwood.org AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Waggy, Melissa, A. 2010. Phalaris arundinacea. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2010, August 19]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: PHAARU NRCS PLANT CODE [282]: PHAR3 COMMON NAMES: reed canarygrass canary grass reed canary grass reed canary-grass speargrass ribbon grass http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/graminoid/phaaru/all.html[8/19/2010 12:03:24 PM] Phalaris arundinacea gardener's gaiters TAXONOMY: The scientific name of reed canarygrass is Phalaris arundinacea L. (Poaceae) [14,83,87,111,113,141,187,192,298]. A variegated type, Phalaris arundinacea var. picta L. or ribbon grass, also occurs in North America [14]. Reed canarygrass has been bred for cultivation and at least 11 cultivars have been developed [102]. Terminology used to describe reed canarygrass' phenotypic variability (e.g., strains, types, genotypes, ecotypes) is inconsistent in the literature. This review uses the terminology from the original publications unless it is unclear and/or inconsistent -

Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris Arundinacea Subsp

Invasive Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea subsp. arundinacea) Best Management Practices in Ontario ontario.ca/invasivespecies BLEED Foreword These Best Management Practices (BMPs) are designed to provide guidance for managing the invasive species of Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea subsp. arundinacea) in Ontario. Funding and leadership in the development of this document was provided by Environment Canada - Canadian Wildlife Service, and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The BMPs were developed by the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC) and partners. These guidelines were created to complement the invasive plant control initiatives of organizations and individuals concerned with the protection of biodiversity, species at risk, infrastructure, and natural lands. These BMPs are based on the most effective and environmentally safe control practices known from research and experience. They reflect current provincial and federal legislation regarding pesticide usage, habitat disturbance and species at risk protection. These BMPs are subject to change as legislation is updated or new research findings emerge. They are not intended to provide legal advice, and interested parties are advised to refer to the applicable legislation to address specific circumstances. Check the website of the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (www.ontarioinvasiveplants.ca) or Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (www.ontario.ca/invasivespecies) for updates. Anderson, Hayley. 2012. Invasive Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea subsp. arundinacea) -

Technical Note 40: Biology, History and Suppression of Reed Canarygrass

TECHNICAL NOTE USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service Boise, Idaho TN PLANT MATERIALS NO. 40 February, 2001 BIOLOGY, HISTORY, AND SUPPRESSION OF REED CANARYGRASS (Phalaris arundinacea L.) Mark Stannard, Pullman PMC Team Leader Wayne Crowder, Pullman PMC Asst. Mgr. • It is native to North America, Europe, Asia and Africa. • Reed canarygrass is perennial, rhizomatous, and effectively excludes other vegetation. • It is tremendously productive on moist soils and will sequester large amounts of soil nutrients. • It has been in use as a pasture grass since the early 1800’s in North America, and has been in use in the Pacific Northwest since the 1880’s. • It is a popular plant for pollution control of municipal & industrial waste water. • Reed canarygrass does not tolerate ponded water, repeated tillage, repeated defoliation, or dense shade. • Several herbicides will kill reed canarygrass but only one is labeled for use in wetlands. • Much of its competitiveness resides in its ability to shade out competitors and in its stand persistence. • Effective control integrates suppressing growth and filling the void to prevent reinfestation. Biology reed canarygrass to rapidly expand its local territory and a single rhizome or stem can infest an entire drainage. Reed canarygrass is a cool-season grass that primarily occurs across the northern tier states. It is native to Reed canarygrass culms are also capable of rooting and North America, northern Europe, Mongolia, Japan, China, the former Soviet Union, northern Afghanistan, and even South Africa (Tsvelev 1983). David Douglas (1830’s), David Lyall (1860), and the Fremont expedition (1844) either collected or documented the occurrence of reed canarygrass in the Pacific Northwest before 1860. -

Reed Canary-Grass Marsh System

Bluejoint – Reed Canary-grass Marsh System: Palustrine Subsystem: Herbaceous PA Ecological Group(s): Basin Wetland Global Rank: GNR State Rank: S5 General Description These marshes occur in a variety of landscape settings, from river backwaters to upland depressions. The most typical species are bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis) and reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea). Associates vary widely, but commonly include mannagrass (Glyceria spp.), rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides), three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum var. arundinaceum), Joe-Pye- weed (Eutrochium fistulosum, E. maculatum), common cat-tail (Typha latifolia), swamp dewberry (Rubus hispidus), wool-grass (Scirpus cyperinus) and other Scirpus spp. The invasive species, common reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), narrow-leaved cat-tail (Typha angustifolia) and Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), are frequently a major problem in these systems. Rank Justification Common, widespread, and abundant in the jurisdiction. Identification Dominated by bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis) and co-dominated by reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea) Soils are typically mineral soil or well-decomposed peat, with a thick root mat Water regime varies between temporarily and seasonally flooded Graminoid cover is typically dense Characteristic Species Herbs Canada bluejoint (Calamagrostis canadensis var. canadensis) Reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea) Rice cutgrass (Leersia oryzoides) Three-way