Assessing Research About the Gwangju Uprising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6/06 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising

8/1/2020 Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising Neoliberalism and the Gwangju Uprising By Georgy Katsiaficas Abstract Drawing from US Embassy documents, World Bank statistics, and memoirs of former US Ambassador Gleysteen and Commanding General Wickham, US actions during Chun Doo Hwan’s first months in power are examined. The Embassy’s chief concern in this period was liberalization of the Korean economy and securing US bankers’ continuing investments. Political liberalization was rejected as an appropriate goal, thereby strengthening Korean anti-Americanism. The timing of economic reforms and US support for Chun indicate that the suppression of the Gwangju Uprising made possible the rapid imposition of the neoliberal accumulation regime in the ROK. With the long-term success of increasing American returns on investments, serious strains are placed on the US/ROK alliance. South Korean Anti-Americanism Anti-Americanism in South Korea remains a significant problem, one that simply won’t disappear. As late as 1980, the vast majority of South Koreans believed the United States was a great friend and would help them achieve democracy. During the Gwangju Uprising, the point of genesis of contemporary anti-Americanism, a rumor that was widely believed had the aircraft carrier USS Coal Sea entering Korean waters to aid the insurgents against Chun Doo Hwan and the new military dictatorship. Once it became apparent that the US had supported Chun and encouraged the new military authorities to suppress the uprising (even requesting that they delay the re-entry of troops into the city until after the Coral Sea had arrived), anti-Americanism in South Korea emerged with startling rapidity and unexpected longevity. -

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

Status of HPV Vaccination Among HPV-Infected Women Aged 20–60 Years with Abnormal Cervical Cytology in South Korea: a Multicenter, Retrospective Study

J Gynecol Oncol. 2020 Jan;31(1):e4 https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2020.31.e4 pISSN 2005-0380·eISSN 2005-0399 Original Article Status of HPV vaccination among HPV-infected women aged 20–60 years with abnormal cervical cytology in South Korea: a multicenter, retrospective study Jaehyun Seong ,1 Sangmi Ryou ,1 Myeongsu Yoo ,1 JeongGyu Lee ,1 Kisoon Kim ,1 Youngmee Jee ,2 Chi Heum Cho ,3 Seok Mo Kim ,4 Sung Ran Hong ,5 Dae Hoon Jeong ,6 Won-Chul Lee ,7 Jong Sup Park ,8 Tae Jin Kim ,9 Mee-Kyung Kee 1 1Division of Viral Diseases Research, Center for Infectious Diseases Research, Korea National Institute of Received: Feb 1, 2019 Health, Cheongju, Korea Revised: Jun 12, 2019 2Center for Infectious Diseases Research, Korea National Institute of Health, Cheongju, Korea Accepted: Jun 19, 2019 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea Correspondence to 5Department of Pathology, Cheil General Hospital and Women's Healthcare Center, Dankook University Mee-Kyung Kee College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Division of Viral Disease Research, Center for 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, University College of Infectious Diseases Research, Korea National Medicine, Busan, Korea Institute of Health, 187 Osongsaengmyeong 7Department of Preventive Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 2-ro, Osong-eup, Heungdeok-gu, 8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea Cheongju 28159, Korea. College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 9 E-mail: [email protected] Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Cheil General Hospital and Women's Healthcare Center, Dankook University, Seoul, Korea Copyright © 2020. -

Smith Alumnae Quarterly

ALUMNAEALUMNAE Special Issueue QUARTERLYQUARTERLY TriumphantTrT iumphah ntn WomenWomen for the World campaigncac mppaiigngn fortififorortifi eses Smith’sSSmmitith’h s mimmission:sssion: too educateeducac te wwomenommene whowhwho wiwillll cchangehahanngge theththe worldworlrld This issue celebrates a stronstrongerger Smith, where ambitious women like Aubrey MMenarndtenarndt ’’0808 find their pathpathss Primed for Leadership SPRING 2017 VOLUME 103 NUMBER 3 c1_Smith_SP17_r1.indd c1 2/28/17 1:23 PM Women for the WoA New Generationrld of Leaders c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd c2 2/24/17 1:08 PM “WOMEN, WHEN THEY WORK TOGETHER, have incredible power.” Journalist Trudy Rubin ’65 made that statement at the 2012 launch of Smith’s Women for the World campaign. Her words were prophecy. From 2009 through 2016, thousands of Smith women joined hands to raise a stunning $486 million. This issue celebrates their work. Thanks to them, promising women from around the globe will continue to come to Smith to fi nd their voices and their opportunities. They will carry their education out into a world that needs their leadership. SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY Special Issue / Spring 2017 Amber Scott ’07 NICK BURCHELL c2-50_Smith_SP17.indd 1 2/24/17 1:08 PM In This Issue • WOMEN HELPING WOMEN • A STRONGER CAMPUS 4 20 We Set Records, Thanks to You ‘Whole New Areas of Strength’ In President’s Perspective, Smith College President The Museum of Art boasts a new gallery, two new Kathleen McCartney writes that the Women for the curatorships and some transformational acquisitions. World campaign has strengthened Smith’s bottom line: empowering exceptional women. 26 8 Diving Into the Issues How We Did It Smith’s four leadership centers promote student engagement in real-world challenges. -

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844

An Alabama School Girl in Paris 1842-1844 the letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and her family Nancyt/ M. Rohr_____ _ An Alabama School Girl in Paris, 1842-1844 The Letters of Mary Fenwick Lewis and Her Family Edited by Nancy M. Rohr An Alabama School Girl In Paris N a n c y M. Ro h r Copyright Q 2001 by Nancy M. Rohr All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the editor. ISPN: 0-9707368-0-0 Silver Threads Publishing 10012 Louis Dr. Huntsville, AL 35803 Second Edition 2006 Printed by Boaz Printing, Boaz, Alabama CONTENTS Preface...................................................................................................................1 EditingTechniques...........................................................................................5 The Families.......................................................................................................7 List of Illustrations........................................................................................10 I The Lewis Family Before the Letters................................................. 11 You Are Related to the Brave and Good II The Calhoun Family Before the Letters......................................... 20 These Sums will Furnish Ample Means Apples O f Gold in Pictures of Silver........................................26 III The Letters - 1842................................................................................. 28 IV The Letters - 1843................................................................................ -

International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea Tribunal International Du Droit De La Mer

INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNAL FOR THE LAW OF THE SEA TRIBUNAL INTERNATIONAL DU DROIT DE LA MER MINUTES OF PUBLIC SITTINGS MINUTES OF THE PUBLIC SITTINGS HELD ON 1, 6, 7 AND 18 DECEMBER 2004 The “Juno Trader” Case (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea-Bissau), Prompt Release PROCES-VERBAL DES AUDIENCES PUBLIQUES PROCÈS-VERBAL DES AUDIENCES PUBLIQUES DES 1ER, 6, 7 ET 18 DECEMBRE 2004 Affaire du « Juno Trader » (Saint-Vincent-et-les Grenadines c. Guinée-Bissau), prompte mainlevée For ease of use, in addition to the continuous pagination, this volume also contains, between square brackets at the beginning of each statement, a reference to the pagination of the uncorrected verbatim records. ______________ En vue de faciliter l’utilisation de l’ouvrage, le présent volume comporte, outre une pagination continue, l’indication, entre crochets, au début de chaque exposé, de la pagination des procès-verbaux non corrigés. Minutes of the Public Sittings held on 1, 6, 7 and 18 December 2004 Procès-verbal des audiences publiques des 1er, 6, 7 et 18 décembre 2004 OPENING OF THE ORAL PROCEEDINGS – 1 December 2004, p.m. PUBLIC SITTING HELD ON 1 DECEMBER 2004, 4.00 P.M. Tribunal Present: President NELSON; Judges CAMINOS, MAROTTA RANGEL, YANKOV, YAMAMOTO, KOLODKIN, PARK, MENSAH, CHANDRASEKHARA RAO, AKL, ANDERSON, WOLFRUM, TREVES, MARSIT, NDIAYE, JESUS, XU, COT and LUCKY; Registrar GAUTIER. AUDIENCE PUBLIQUE DU 1ER DECEMBRE 2004, 16 H 00 Tribunal Présents : M. NELSON, Président; MM. CAMINOS, MAROTTA RANGEL, YANKOV, YAMAMOTO, KOLODKIN, PARK, MENSAH, CHANDRASEKHARA RAO, AKL, ANDERSON, WOLFRUM, TREVES, MARSIT, NDIAYE, JESUS, XU, COT et LUCKY, juges; M. -

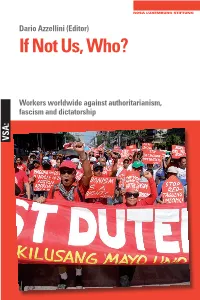

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

The GW Undergraduate Review, Volume 4

41 KEYWORDS: Korean democracy, Gwangju Uprising, art censorship DOI: https://doi.org/10.4079/2578-9201.4(2021).08 The Past and Present of Cultural Censorship in South Korea: Minjung Art During and After the Gwangju Uprising VIVIAN KONG INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, ESIA ‘23, [email protected] ABSTRACT The Gwangju Uprising provided pivotal momentum for South Korea’s path toward democracy and was assisted by the artwork by Minjung artists. However, the state’s continuous censorship of democratic art ironically contradicts with the principles that Gwangju upholds, generating the question: how does the censorship of democratic artists during and after the Gwangju Democratic Uprising affect artistic political engagement and reflect upon South Korea’s democracy? I argue that censorship of Minjung art is hypocritical in nature by providing key characteristics of democracy the South Korean state fails to meet. Minjung art intends to push for political change and has roots in the Gwangju Uprising, an event that was the catalyst in creating a democratic state, yet the state continues to suppress a democratic freedom of expression. Looking to dissolve the line between activism and art, Korean Minjung artists have been producing content criticizing the state from the 1980s to modern day despite repression from the state. Past studies and first-person accounts on Gwangju have focused separately on authoritarian censorship on art or on modern cultural censorship. This paper seeks to bridge this gap and identify the parallels between artistic censorship during South Korea’s dictatorships and during its democracy to identify the hypocrisy of the state regarding art production and censorship. -

Parent Student Handbook

PARENT-STUDENT HANDBOOK 2020-2021 www.siskorea.org 2020-2021 SCHOOL CALENDAR August (14 school days) February (18 school days) S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 11 ES New Students’/Parents’ Orientation 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 Intent Form to Parents HS & MS New Students’/Parents’ 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 11-12 Lunar Holiday (School Closed) Orientation/HS Freshman Orientation 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 15 Deadline for New Applications 12 First Day of School 12:00 p.m. Dismissal 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 22 Deadline for Return of Intent Forms 31 ES/MS Students 12:00 p.m. Dismissal 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 Elementary/Middle School 30 31 Writing Prompt 1 Samil Day (School Closed) September (19 school days) March (19 school days) Faculty Professional Development 3 End of Second Trimester (60 Days) Vision and Mission Statements S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 Elementary Open House 8 Re-Enrollment Payment Due for 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Returning Students 2 Middle School Open House 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 3 High School Open House 8 Elementary/Middle School Writing 19 Family Fun Day 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Prompt 28-30 Chuseok Holiday (School Closed) 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 ES/MS Students 12:00 p.m. -

Truth and Reconciliation� � Activities of the Past Three Years�� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �

Truth and Reconciliation Activities of the Past Three Years CONTENTS President's Greeting I. Historical Background of Korea's Past Settlement II. Introduction to the Commission 1. Outline: Objective of the Commission 2. Organization and Budget 3. Introduction to Commissioners and Staff 4. Composition and Operation III. Procedure for Investigation 1. Procedure of Petition and Method of Application 2. Investigation and Determination of Truth-Finding 3. Present Status of Investigation 4. Measures for Recommendation and Reconciliation IV. Extra-Investigation Activities 1. Exhumation Work 2. Complementary Activities of Investigation V. Analysis of Verified Cases 1. National Independence and the History of Overseas Koreans 2. Massacres by Groups which Opposed the Legitimacy of the Republic of Korea 3. Massacres 4. Human Rights Abuses VI. MaJor Achievements and Further Agendas 1. Major Achievements 2. Further Agendas Appendices 1. Outline and Full Text of the Framework Act Clearing up Past Incidents 2. Frequently Asked Questions about the Commission 3. Primary Media Coverage on the Commission's Activities 4. Web Sites of Other Truth Commissions: Home and Abroad President's Greeting In entering the third year of operation, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea (the Commission) is proud to present the "Activities of the Past Three Years" and is thankful for all of the continued support. The Commission, launched in December 2005, has strived to reveal the truth behind massacres during the Korean War, human rights abuses during the authoritarian rule, the anti-Japanese independence movement, and the history of overseas Koreans. It is not an easy task to seek the truth in past cases where the facts have been hidden and distorted for decades. -

Nationalism in Crisis: the Reconstruction of South Korean Nationalism in Korean History Textbooks (Han’Guksa)

Nationalism in Crisis: The Reconstruction of South Korean Nationalism in Korean History Textbooks (Han’guksa) by Yun Sik Hwang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Yun Sik Hwang 2016 Nationalism in Crisis: The Reconstruction of South Korean Nationalism in Korean History Textbooks (Han’guksa) Yun Sik Hwang Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2016 Abstract South Korea has undergone considerable transitions between dictatorship and democracy under Korea’s extraordinary status as a divided nation. The nature of this division developed an intense political contestation in South Korea between the political Left who espouse a critical view of top-down national history, and the Right who value the official view of South Korea’s national history. Whether it is a national history or nationalist history, in terms of conceptions of national identity and nationalism in relation to Korean history, disagreement continues. The purpose of this thesis is not to support nor refute the veracity of either political position, which is divided between a sensationalized political Right and a caricaturized Left. The aim of this project is to evaluate a series of developments in Korean history textbooks that can be seen as a recent attempt to build new national identities. ii Acknowledgments There are countless people I am indebted as I completed this Master’s thesis. First and foremost, I would like to thank my professor and supervisor, Andre Schmid for his charismatic and friendly nature for the past 7 years. -

8Th Korean Screen Cultures Conference Conference Programme

2019 8th Korean Screen Cultures Conference Conference Programme UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE JUNE 5-7 2019 SPONSORED BY THE KOREA FOUNDATION KSCC 2019 Programme Schedule & Panel Plan Wednesday 5th June Time Event Location 16:50-17:05 Meet at Legacy Hotel lobby and walk to UCLan Legacy Hotel 17:05-17:30 Early-bird registration open Mitchell Kenyon Foyer 17:05-17:30 Wine and Pizza Opening Reception Mitchell Kenyon Foyer 17:30-19:30 Film Screening: Snowy Road (2015) Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 19:30-19:55 Director Q&A with Lee, Na Jeong Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 20:00-21:30 Participants invited join an unofficial conference dinner Kim Ji Korean Restaurant Thursday 6th June 08:45-09:00 Meet at Legacy Hotel lobby and walk to UCLan Legacy Hotel 09:00-09:15 Registration & Morning Coffee Foster LT Foyer 09:15-09:30 Opening Speeches FBLT4 09:30-11:00 Panel 1A: Horror Film and Drama FBLT4 09:30-11:00 Panel 1B: Transnational Interactions FBLT3 11:00-12:20 Coffee Break Foster LT Foyer 11:20-11:50 Education Breakout Session FBLT4 11:20-11:50 Research Breakout Session FBLT3 11:50 -13:20 Panel 2A: Industry and Distribution FBLT4 11:50 -13:20 Panel 2B: Diverse Screens FBLT3 13:20-14:20 Buffet Lunch Foster Open Space 14:25-15:55 Panel 3A: History/Memory/Reception FBLT4 14:25-15:55 Panel 3B: Korean Auteurs FBLT3 15:55-16:15 Coffee & Cake Break Foster LT Foyer 16:15-17:15 Keynote: Rediscovering Korean Cinema FBLT4 17:15-18:45 Film Screening: Tuition (1940) Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 18:45-19:15 Q&A with Chunghwa Chong, Korean Film Archive Mitchell Kenyon Cinema