Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

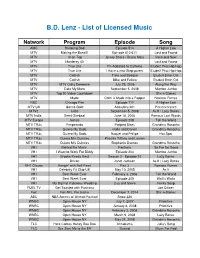

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

In Canadian Labour Law Brian A

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Article 5 Volume 21, Number 3 (October 1983) "Equal Partnership" in Canadian Labour Law Brian A. Langille Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Article Citation Information Langille, Brian A.. ""Equal Partnership" in Canadian Labour Law." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 21.3 (1983) : 496-536. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol21/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. "EQUAL PARTNERSHIP" IN CANADIAN LABOUR LAW By BRIAN A. LANGILLE* I. THE ISSUE ............................................... 497 II. AN AMERICAN STARTING POINT ......................... 499 III. THE SCOPE OF THE DUTY TO BARGAIN IN CANADA ...... 503 IV. CERTIFICATION AND CERTIFICATES ..................... 506 V. AN EVALUATION ........................................ 508 VI. OTHER PARTS OF THE PUZZLE ........................... 512 A. The Statutory Timetable .................................. 512 B. The FunctionalContent of the Duty to Bargain .............. 514 C. The Freeze ............................................. 523 D. UnfairLabour Practices.................................. 528 E. The ArbitrationJurisprudence on ContractingOut ........... 532 VII. CONCLUSION ............................................ 536 © Copyright, 1983, Brian A. Langille. * Associate Professor of Law, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto. 1983] Partnershipsin LabourLaw ... by permiting labour to organize freely and effectively we can convert the relation of master and servant in to an equal and cooperativepartnership.... I Senator Wagner (1932) ... Congress had no expectation that the elected union representative2 would become an equalpartnerin the running of the business enterprise. Blackmun J. (1981) The union is an equalpartner ... 3 Canada Labour Relations Board (1981) (Dorsey, Vice Chairman) We cannot subscribe to an interpretation . -

Unions Matter

Unions Matter How the Ability of Labour Unions to Reduce Income Inequality and Influence Public Policy has been affected by Regressive Labour Laws Garry Sran with Michael Lynk, James Clancy and Derek Fudge Abstract Copyright March 2013: Ottawa Canadian Foundation for Labour Rights THERE IS EXTENSIVE RESEARCH literature that suggests Design and layout by Skip Hambling there are significant social benefits for countries with strong labour rights and a more extensive collective bargaining The Canadian Foundation for Labour Rights (CFLR) is a system. Income inequality is less extreme according to a national voice devoted to promoting labour rights as an im- variety of measures, civic engagement is higher, there are portant means to strengthening democracy, equality and more extensive social programs such as health care and economic justice here in Canada and internationally. pensions plans, and the incidence of poverty is significant- www.labourrights.ca ly smaller. This paper adds to the literature by examining the relationship between labour unions, income inequal- CFLR was established and is sponsored by the ity and regressive labour laws. National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE). www.nupge.ca The underlying causes of declining unionization rates will be examined for Canada and will be compared to other The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of developed economies. C. Meyer, M. Luff, B. Hildahl and D. Wells in the preparation of this paper. The paper finds that regressive labour laws in Canada have reduced unionization rates which has led to rising income inequality and reduced civic participation. UNIONS MATTER | CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR LABOUR RIGHTS 1 n 1 Introduction FOR OVER 30 YEARS income inequality in Canada and throughout the world has been rising. -

Human-Black Bear Conflict a Review of the Most Common Management Practices

HUMAN-BLACK BEAR CONFLICT A REVIEW OF THE MOST COMMON MANAGEMENT PRACTICES A black bear in Lake Tahoe, NV. Photo courtesy Urbanbearfootage.com 1 A black bear patrols downtown Carson City, NV. Photo courtesy Heiko De Groot 2 Authors Carl W. Lackey (Nevada Department of Wildlife) Stewart W. Breck (USDA-WS-National Wildlife Research Center) Brian Wakeling (Nevada Department of Wildlife; Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies) Bryant White (Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies) 3 Table of Contents Preface Acknowledgements Introduction . The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and human-bear conflicts . “I Hold the Smoking Gun” by Chris Parmeter Status of the American Black Bear . Historic and Current distribution . Population estimates and human-bear conflict data Status of Human-Black Bear Conflict . Quantifying Conflict . Definition of Terms Associated with Human-Bear Management Methods to Address Human-Bear Conflicts . Public Education . Law and Ordinance Enforcement . Exclusionary Methods . Capture and Release . Aversive Conditioning . Repellents . Damage Compensation Programs . Supplemental & Diversionary Feeding . Depredation (Kill) Permits . Management Bears (Agency Kill) . Privatized Conflict Management Population Management . Regulated Hunting and Trapping . Control of Non-Hunting Mortality . Fertility Control . Habitat Management . No Intervention Agency Policy Literature Cited 4 Abstract Most human-black bear (Ursus americanus) conflict occurs when people make anthropogenic foods (that is, foods of human origin like trash, dog food, domestic poultry, or fruit trees) available to bears. Bears change their behavior to take advantage of these resources and in the process may damage property or cause public safety concerns. Managers are often forced to focus efforts on reactive non-lethal and lethal bear management techniques to solve immediate problems, which do little to address root causes of human-bear conflict. -

Human–Black Bear Conflicts: a Review of Common Management Practices

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Human–Wildlife Interactions Monographs Berryman Institute 2018 Human–Black Bear Conflicts: A Review of Common Management Practices Carl W. Lackey Nevada Department of Wildlife, [email protected] Stewart W. Breck USDA/APHIS/WS National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Brian F. Wakeling Nevada Department of Wildlife, [email protected] H. Bryant White Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi_monographs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, C. W., S. W. Breck, B. F. Wakeling, and B. White. 2018. Human-Black Bear Conflicts: A er view of common management practices. Human-Widlife Interactions Monograph 2:1-68. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Berryman Institute at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human–Wildlife Interactions Monographs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN–BLACK BEAR CONFLICTS A REVIEW OF COMMON MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Carl W. Lackey Stewart W. Breck Brian F. Wakeling Bryant White HUMAN-WILDLIFE INTERACTIONS MONOGRAPH NUMBER 2 Human-Wildlife Interactions: Monograph 2. A publication of the Jack H. Berryman Institute Press, Wildland Resources Department, Utah State University, Logan, Utah, USA. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to a large number of people and organizations for their support of this publication and their assistance in bringing it to fruition, including Richard Beausoleil (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife), Jeremy Hurst (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation), and Carole Stanko (New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife). -

06 SM 9/21 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 21, 2004 Monday Evening September 27, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Benefactor Monday Night Football:Cowboys @ Redskins Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Listen Up Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor Las Vegas LAX Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore Renovate My Family Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Parole Squad Plots Gotti Airline Airline Crossing Jordan Parole Squad AMC The Wrecking Crew Mother, Jugs and Speed Sixteen Candles ANIM Growing Up Lynx Growing Up Rhino Miami Animal Police Growing Up Lynx Growing Up Rhino CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage Norton TV DISN Disney Movie: TBA Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! THS E!ES Dr. 90210 Howard Stern SNL ESPN Monday Night Countdown Hustle EOE Special Sportscenter ESPN2 Hustle WNBA Playoffs Shootarou Dream Job Hustle FAM The Karate Kid Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX The Animal Fear Factor King of the Hill Cops HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST UFO Files Deep Sea Detectives Investigating History Tactical To Practical UFO Files LIFE Too Young to be a Dad Torn Apart How Clea Golden Nanny Nanny MTV MTV Special Road Rules The Osbo Real World Video Clash Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes Threes SCI Stargate -

2013 2013 5Th International Conference on Cyber Conflict

2013 2013 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict PROCEEDINGS K. Podins, J. Stinissen, M. Maybaum (Eds.) 4-7 JUNE 2013, TALLINN, ESTONIA 2013 5TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CYBER CONFLICT (CYCON 2013) Copyright © 2013 by NATO CCD COE Publications. All rights reserved. IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1326N-PRT ISBN 13 (print): 978-9949-9211-4-0 ISBN 13 (pdf): 978-9949-9211-5-7 ISBN 13 (epub): 978-9949-9211-6-4 Copyright and Reprint Permissions No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence ([email protected]). This restriction does not apply to making digital or hard copies of this publication for internal use within NATO, and for personal or educational use when for non-profit or non- commercial purposes, providing that copies bear this notice and a full citation on the first page as follows: [Article author(s)], [full article title] 2013 5th International Conference on Cyber Conflict K. Podins, J. Stinissen, M. Maybaum (Eds.) 2013 © NATO CCD COE Publications Printed copies of this publication are available from: NATO CCD COE Publications Filtri tee 12, 10132 Tallinn, Estonia Phone: +372 717 6800 Fax: +372 717 6308 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ccdcoe.org Layout: Marko Söönurm Legal Notice: This publication contains opinions of the respective authors only. They do not necessarily reflect the policy or the opinion of NATO CCD COE, NATO, or any agency or any government. -

Halper Sued Jerome Co

60 / 43 HOLDING STEADY Feed costs expected to stay stable again this years >>> Scattered AGRIBUSINESS 1 showers. Main 10 ON THE LINKS >>> On first day of state golf, area teams all within striking distance of leaders, SPORTS 1 TUESDAY 75 CENTS May 18, 2010 TIMES-NEWS Magicvalley.com Deadline looms for TFSD contract negotiations Judge “The Legislature set a difficult Jerome, Mini-Cassia PUBLIC SCHOOL CUTS timeline,” said Attorney Brian Julian, with the Boise-based firm dismisses Area school districts are renegotiating teacher contracts to deal with a fiscal year schools also facing 2011 decrease in state funding coming to public schools in July. Here’s a sampling Anderson, Julian and Hull, recom- of approved or proposed cost-saving measures. mending the board not push the vote on pay reductions due process hearing into June. Cuts approved • 12 furlough days for administrators, jail lawsuit “There are events that will take By Blair Koch Gooding School District: representing a 6.3 percent reduction place after the hearing … we can’t Times-News correspondent • 4.35 percent pay reduction for admin- wait because of the timeline.” Halper sued Jerome Co. istrators Jerome School District: If needed, the due process hear- The Twin Falls School District • 5.6 percent pay reduction for superin- • 1 percent pay reduction for teachers ing would give the district and over jail funding issues and the Twin Falls Education tendent and administrators and 10 furlough association an opportunity to Association have three weeks to • Four furlough days, representing 3.6 days, representing a 5 percent reduc- present evidence to support why, By Andrea Jackson finalize a new teacher contract for percent reduction for teachers tion or why not, the reductions are Times-News writer the upcoming school year. -

06 SM 7/20 (TV Guide)

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, July 20, 2004 Monday Evening July 26, 2004 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Wife & Kid GLopez According Hope Fait Primetime Local Local Jimmy K KBSH/CBS Still Stand Yes Dear Raymond Two Men CSI Miami Local Late Show Late Late KSNK/NBC Fear Factor For Love Or Money Political Programming Local Tonight Show Conan FOX North Shore The Casino Local Local Local Local Local Local Cable Channels A&E Cold Case Fam Plots Fam Plots Airline Airline UK Crossing Jordan Cold Case AMC Once Upon A Time In the West Arrowhead ANIM Growing Up Elephant Animal Lifeline Animal Cops - Detroit Growing Up Elephant Animal Lifeline CNN Paula Zahn Now Larry King Live Newsnight Lou Dobbs Larry King Norton TV DISC Monster House Monster Garage American Chopper Monster House Monster Garage DISN Stuck in the Suburbs Raven Sis Bug Juice Lizzie Boy Meets Even E! Young Divas Dr. 90210 Howard Stern The "What The" Awar ESPN Monday Night Baseball Sportscenter Outside Sportscen ESPN2 ATP Masters Playmakers Carquest FAM Crimes of Fashion Whose Lin Whose Lin The 700 Club Funniest Funniest FX Courage Under Fire Rescue Me Courage Under Fire HGTV Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce Organize Dsgn Chal Dsgn Dim Dsgn Dme To Go Hunters Smrt Dsgn Decor Ce HIST UFO Files Deep Sea Detectives Investigating History The Shroud of Turin UFO Files LIFE Providence Locked Up: A Mothers Rage Golden Gr Golden Gr Nanny Nanny MTV Making Vi Special Road Rule Road Rule Road Rule Assistant MTV Special TRL Listings: NICK SpongeBo Drake Full Hous Full Hous -

June 2015 Sales Kit: Fiction & Nonfiction

JUNE 2015 FICTION ORDERS IN 15 April 2015 IN-STORE 29 May 2015 JUNE 2015 Palace of Tears Julian Leatherdale A shining story of family, passion, secrets and vengeance woven through the hardships of both World Wars, and always bringing us back to The Palace, a mountain hotel famed equally for its luxury and for its mysterious owner. Description Angie loved Mr Fox's magnificent, absurd hotel. In fact, it was her one true great love. But ... today Angie was so cross, so fed up with everybody and everything, she would probably cheer if a wave of fire swept over the cliff and engulfed the Palace and all its guests. A sweltering summer's day, January 1914: the charismatic and ruthless Adam Fox throws a lavish birthday party for his son and heir at his elegant clifftop hotel in the Blue Mountains. Everyone is invited except Angie, the girl from the cottage next door. The day will end in tragedy, a punishment for a family's secrets and lies. In 2013, Fox's granddaughter Lisa, seeks the truth about the past. Who is this Angie her mother speaks of: 'the girl who broke all our hearts'? Why do locals call Fox's hotel the 'palace of tears'? Behind the grandeur and glamour of its famous guests and glittering parties, Lisa discovers a hidden history of passion and revenge, loyalty and love. A grand piano burns in the night, a seance promises death or forgiveness, a fire rages in a snowstorm, a painter's final masterpiece inspires betrayal, a child is given away. -

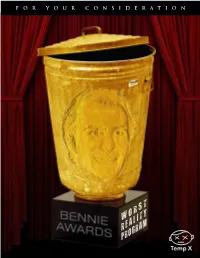

Worst Reality Program PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK the Vexcon Pest Removal Team Helps to Rid Clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E Their Extreme Pest Cases

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION WORST REALITY PROGRAM PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK The Vexcon pest removal team helps to rid clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E their extreme pest cases. Performance series featuring Criss Angel, a master Criss Angel: Mindfreak illusionist known for his spontaneous street A&E performances and public shows. Reality series which focuses on bounty hunter Duane Dog the Bounty Hunter "Dog" Chapman, his professional life as well as the A&E home life he shares with his wife and their 12 children. A docusoap following the family life of Gene Simmons, Gene Simmons Family Jewels which include his longtime girlfriend, Shannon Tweed, a A&E former Playmate of the Year, and their two children. Reality show following rock star Dee Snider along with Growing Up Twisted A&E his wife and three children. Reality show that follows individuals whose lives have Hoarders A&E been affected by their need to hoard things. Reality series in which the friends and relatives of an individual dealing with serious problems or addictions Intervention come together to set up an intervention for the person in A&E the hopes of getting his or her life back on track. Reality show that follows actress Kirstie Alley as she Kirstie Alley's Big Life struggles with weight loss and raises her two daughters A&E as a single mom. Documentary relaity series that follows a Manhattan- Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force based federal task that tracks down fugitives in the Tri- A&E state area. Individuals with severe anxiety, compulsions, panic Obsessed attacks and phobias are given the chance to work with a A&E therapist in order to help work through their disorder. -

1 United States District Court for The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ________________________________________ ) VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC., ) COMEDY PARTNERS, ) COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION, INC., ) PARAMOUNT PICTURES ) Case No. 1:07-CV-02103-LLS CORPORATION, ) (Related Case No. 1:07-CV-03582-LLS) and BLACK ENTERTAINMENT ) TELEVISION LLC, ) DECLARATION OF WARREN ) SOLOW IN SUPPORT OF Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR v. ) PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) YOUTUBE, INC., YOUTUBE, LLC, and ) GOOGLE INC., ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________ ) I, WARREN SOLOW, declare as follows: 1. I am the Vice President of Information and Knowledge Management at Viacom Inc. I have worked at Viacom Inc. since May 2000, when I was joined the company as Director of Litigation Support. I make this declaration in support of Viacom’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Liability and Inapplicability of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbor Defense. I make this declaration on personal knowledge, except where otherwise noted herein. Ownership of Works in Suit 2. The named plaintiffs (“Viacom”) create and acquire exclusive rights in copyrighted audiovisual works, including motion pictures and television programming. 1 3. Viacom distributes programs and motion pictures through various outlets, including cable and satellite services, movie theaters, home entertainment products (such as DVDs and Blu-Ray discs) and digital platforms. 4. Viacom owns many of the world’s best known entertainment brands, including Paramount Pictures, MTV, BET, VH1, CMT, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and SpikeTV. 5. Viacom’s thousands of copyrighted works include the following famous movies: Braveheart, Gladiator, The Godfather, Forrest Gump, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Top Gun, Grease, Iron Man, and Star Trek.