Expressing the Construction of the Autobiographical Self in Craig Thompson's Blankets, a Layering of Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Craig Thompson, Whose Latest Book Is, "Habibi," a 672-Page Tour De Force in the Genre

>> From the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. >> This is Jennifer Gavin at The Library of Congress. Late September will mark the 12th year that book lovers of all ages have gathered in Washington, DC to celebrate the written word of The Library of Congress National Book Festival. The festival, which is free and open to the public, will be 2 days this year, Saturday, September 22nd, and Sunday, September 23rd, 2012. The festival will take place between 9th and 14th Streets on ten National Mall, rain or shine. Hours will be from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday, the 22nd, and from noon to 5:30 p.m. on Sunday the 23rd. For more details, visit www.loc.gov/bookfest. And now it is my pleasure to introduce graphic novelist Craig Thompson, whose latest book is, "Habibi," a 672-page tour de force in the genre. Mr. Thompson also is the author of the graphic novels, "Good-bye, Chunky Rice," "Blankets," and "Carnet de Voyage." Thank you so much for joining us. >> Craig Thompson: Thank you, Jennifer. It's a pleasure to be here. >> Could you tell us a bit about how you got into not just novel writing, but graphic novel writing? Are you an author who happens to draw beautifully, or an artist with a story to tell? >> Craig Thompson: Well, as a child I was really into comic books, and in a sort of natural adult progression fell out of love with the medium around high school, and was really obsessed with film and then animation, and was sort of mapping out possible career animation, and became disillusioned with that for a number of reasons. -

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011 Table of Contents: Fact Sheet 3 Why I Chose Top Shelf 4 Interview with Chris Staros 5 Book Review: Blankets by Craig Thompson 12 2 Fact Sheet: Top Shelf Productions Web Address: www.topshelfcomix.com Founded: 1997 Founders: Brett Warnock & Chris Staros Editorial Office Production Office Chris Staros, Publisher Brett Warnock, Publisher Top Shelf Productions Top Shelf Productions PO Box 1282 PO Box 15125 Marietta GA 30061-1282 Portland OR 97293-5125 USA USA Distributed by: Diamond Book Distributors 1966 Greenspring Dr Ste 300 Timonium MD 21093 USA History: Top Shelf Productions was created in 1997 when friends Chris Staros and Brett Warnock decided to become publishing partners. Warnock had begun publishing an anthology titled Top Shelf in 1995. Staros had been working with cartoonists and had written an annual resource guide The Staros Report regarding the best comics in the industry. The two joined forces and shared a similar vision to advance comics and the graphic novel industry by promoting stories with powerful content meant to leave a lasting impression. Focus: Top Shelf publishes contemporary graphic novels and comics with compelling stories of literary quality from both emerging talent and known creators. They publish all-ages material including genre fiction, autobiographical and erotica. Recently they have launched two apps and begun to spread their production to digital copies as well. Activity: Around 15 to 20 books per year, around 40 titles including reprints. Submissions: Submissions can be sent via a URL link, or Xeroxed copies, sent with enough postage to be returned. -

Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan

Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel By DJ Dycus Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan : Honing the Hybridity of the Graphic Novel, by DJ Dycus This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by DJ Dycus All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3527-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3527-5 For my girls: T, A, O, and M TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix CHAPTER ONE .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMICS The Fundamental Nature of this Thing Called Comics What’s in a Name? Broad Overview of Comics’ Historical Development Brief Survey of Recent Criticism Conclusion CHAPTER TWO ........................................................................................... 33 COMICS ’ PLACE WITHIN THE ARTISTIC LANDSCAPE Introduction Comics’ Relationship to Literature The Relationship of Comics to Film Comics’ Relationship to the Visual Arts Conclusion CHAPTER THREE ........................................................................................ 73 CHRIS WARE AND JIMMY CORRIGAN : AN INTRODUCTION Introduction Chris Ware’s Background and Beginnings in Comics Cartooning versus Drawing The Tone of Chris Ware’s Work Symbolism in Jimmy Corrigan Ware’s Use of Color Chris Ware’s Visual Design Chris Ware’s Use of the Past The Pacing of Ware’s Comics Conclusion viii Table of Contents CHAPTER FOUR ....................................................................................... -

Introduction to Comics Studies English 280· Summer 2018 · CRN 42457

Introduction to Comics Studies English 280· Summer 2018 · CRN 42457 Instructor: Dr. Andréa Gilroy · email: [email protected] · Office Hours: MWF 12-1:00 PM & by appointment All office hours conducted on Canvas Chat. You can message me personally for private conversation. Comics are suddenly everywhere. Sure, they’re in comic books and the funny pages, but now they’re on movie screens and TV screens and the computer screens, too. Millions of people attend conventions around the world dedicated to comics, many of them wearing comic-inspired costumes. If a costume is too much for you, you can find a comic book t-shirt at Target or the local mall wherever you live. But it’s not just pop culture stuff; graphic novels are in serious bookstores. Graphic novelists win major book awards and MacArthur “Genius” grants. Comics of all kinds are finding their way onto the syllabi of courses in colleges across the country. So, what’s the deal with comics? This course provides an introduction to the history and aesthetic traditions of Anglo-American comics, and to the academic discipline of Comics Studies. Together we will explore a wide spectrum of comic-art forms (especially the newspaper strip, the comic book, the graphic novel) and to a variety of modes and genres. We will also examine several examples of historical and contemporary comics scholarship. Objectives: This term, we will work together to… …better understand the literary and cultural conventions of the comics form. …explore the relevant cultural and historical information which will help situate texts within their cultural, political, and historical contexts. -

20090610 Board Packet Document #12-37

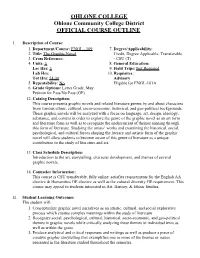

OHLONE COLLEGE Ohlone Community College District OFFICIAL COURSE OUTLINE I. Description of Course: 1. Department/Course: ENGL - 109 7. Degree/Applicability: 2. Title: The Graphic Novel Credit, Degree Applicable, Transferable 3. Cross Reference: - CSU (T) 4. Units: 3 8. General Education: Lec Hrs: 3 9. Field Trips: Not Required Lab Hrs: 10. Requisites: Tot Hrs: 54.00 Advisory 5. Repeatability: No Eligible for ENGL-101A 6. Grade Options: Letter Grade, May Petition for Pass/No Pass (GP) 12. Catalog Description: This course presents graphic novels and related literature genres by and about characters from various ethnic, cultural, socio-economic, historical, and geo-political backgrounds. These graphic novels will be analyzed with a focus on language, art, design, ideology, substance, and content in order to explore the genre of the graphic novel as an art form and literature form as well as to recognize the undercurrent of themes running through this form of literature. Studying the artists’ works and examining the historical, social, psychological, and cultural forces shaping the literary and artistic form of the graphic novel will allow students to become aware of this genre of literature as a unique contribution to the study of literature and art. 13. Class Schedule Description: Introduction to the art, storytelling, character development, and themes of several graphic novels. 14. Counselor Information: This course is CSU transferable, fully online, satisfies requirements for the English AA elective & Humanities GE elective as well as the cultural diversity GE requirement. This course may appeal to students interested in Art, History, & Ethnic Studies. II. Student Learning Outcomes The student will: 1. -

Blankets Craig Thompson

Blankets Craig Thompson A cult classic and one of the bestselling graphic novels of all time. Sales points • First published in the US in 2003, Blankets is new to Faber • Craig Thompson is one of the most highly respected graphic novelists; he has received four Harvey Awards, three Eisner Awards and two Ignatz Awards Description 'Achingly beautiful. a first-love story so well remembered and honest that it reminds you what falling in love feels like.' - Time magazine Wrapped in the landscape of a blustery Wisconsin winter, Blankets explores the sibling rivalry of two brothers growing up in rural isolation, and the budding romance of two young lovers. A tale of security and discovery, of playfulness and tragedy, of a fall from grace and the origins of faith, Blankets is a profound and utterly beautiful work. About the Author Craig Thompson's previous graphic novels include Goodbye, Chunky Rice, Blankets, Carnet de Voyage, Habibi , an Observer Graphic Novel of the Month, a New York Times bestseller, and described by Neel Mukherjee as 'a landmark publication' - and most recently Space Dumplins. His work has received four Harvey Awards, three Eisner Awards and two Ignatz Awards. Price: $39.99 (NZ$45.00) ISBN: 9780571336029 Format: Paperback Dimensions: 228x178mm Extent: 592 pages Main Category: FX Sub Category: Illustrations: Previous Titles: Author now living: Faber Fiction The Map and the Clock: A Laureate's Choice of the Poetry of Britain and Ireland edited by Carol Ann Duffy and Gillian Clarke Now in paperback: a celebration of the most scintillating poems ever composed in Britain, chosen by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy and Gillian Clarke, the National Poet of Wales. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The Graphic Memoir and the Cartoonist’s Memory A Dissertation Presented by Alice Claire Burrows to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University August 2016 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Alice Claire Burrows We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. _________________________________________________________ Raiford Guins, Professor, Chairperson of Defense _________________________________________________________ Robert Harvey, Distinguished Professor, Cultural Analysis & Theory, Dissertation Advisor _________________________________________________________ Krin Gabbard, Professor Emeritus, Cultural Analysis & Theory _________________________________________________________ Sandy Petrey, Professor Emeritus, Cultural Analysis & Theory _________________________________________________________ David Hajdu, Associate Professor, Columbia University, Graduate School of Journalism This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School ___________________________ Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation -

Download PDF (543.6

List of Illustrations Fig. 1: Blankets (360/4). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 257 Fig. 2: Blankets (16). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 260 Fig. 3: Blankets (54). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 266 Fig. 4: Blankets (55). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 267 Fig. 5: Blankets (51). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 272 Fig. 6: Blankets (52). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 273 Fig. 7: Blankets (12). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 277 Fig. 8: Blankets (172). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 281 Fig. 9: Blankets (246/1). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 285 Fig. 10: Blankets (79/1). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 302 Fig. 11: Blankets (88/1). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 303 Fig. 12: Blankets (86/1–3). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. ............... 304 Fig. 13: Blankets (116/1–3). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved. .......... 305 Fig. 14: Blankets (13/4). © 2003 by Craig Thompson. Reprinted by permission of Drawn & Quarterly. -

A Guide to Banned, Challenged, and Controversial Comics and Graphic

READ BANNED COMIC A Guide to Banned, Challenged and Controversial Comics and Graphic Novels Comic Book Legal Defense Fund Director’s Note is a non-profit organization dedi- cated to the protection of the First Happy Banned Books Week! Amendment rights of the comics art form and its community of Every year, CBLDF joins a chorus of readers, advo- retailers, creators, publishers, cates, and organizations to mark the annual cele- librarians, educators, and readers. CBLDF provides legal bration of the freedom to read! We hope you’ll join referrals, representation, advice, us in the celebration by reading banned comics! assistance, and education in furtherance of these goals. In the pages ahead, you’ll see a sampling of the many, many titles singled out for censorship in STAFF American libraries and schools. Censorship has Charles Brownstein, Executive Director Alex Cox, Deputy Director broad targets, from books that capture the unique Georgia Nelson, Development Manager challenges of younger readers, such as Drama by Patricia Mastricolo, Editorial Coordinator Raina Telgemeier and This One Summer by Mariko Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel and Jillian Tamaki, to the frank discussion of adult BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADVISORY BOARD identity found in Fun Home by Alison Bechdel Christina Merkler, President Neil Gaiman & and Maus by Art Spiegelman. The moral, vision- Chris Powell, Vice President Denis Kitchen, Co-Chairs Ted Adams, Treasurer Susan Alston ary realities of authors like Brian K. Vaughan, Neil Dale Cendali, Secretary Greg Goldstein Gaiman, and Alan Moore have all been targeted. Jeff Abraham Matt Groening Jennifer L. Holm Chip Kidd Even the humor and adventure of Dragon Ball and Reginald Hudlin Jim Lee Bone have come under fire. -

4 Cognitive Approaches to Comics Shots – and Conveys a Sense of Continuity in the Scene

4 Cognitive Approaches to Comics 4.1 Synopsis In part 1 I used the term ‘synopsis’ to refer to Wolfgang Iser’s notion that readers generate meaning by ‘seeing things together’, which is guided by tex- tual structures that activate previous themes or gestalten that have become part of the horizon. I developed this idea further by adding conceptual integration theory in part 3, which elaborates on the possible mappings between spaces. Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner identify at least fifteen vital relations (cf. 2003: 101) that become compressed in the blend. In both cases ‘synopsis’ is a metaphor for cognitive operations that are happening in front of the mind’s eye. If we now turn to the architecture of a typical comics page, we find a conceptual illustration and materialisation of this reading model: the fragmented pieces of the narrative – the panels – are separated from each other by a blank space in between – the gutter – that requires readers to cognitively bridge the gulf. Even without any knowledge of gestalt psychology or blending, all comics scholars are challenged to explain how readers are supposed to make sense of this “mosaic art” (Nodelman 2012: 438). As a visualisation of an otherwise cognitive process the medium’s layout also illustrates Iser’s theme and horizon structure, in the sense that the panel(s) attended to by the readers form the present theme and the others around it the horizon. As the ‘wandering viewpoint’ of readers moves on to the next panel, the previous one becomes part of the background: the “theme of one moment becomes the horizon against which the next segment takes on its actuality” (1980: 198; see also Dewey 2005: 199, 211). -

A Graphic Novel and Artist's Book Rosalie Edholm Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2010 Portrait: A Graphic Novel and Artist's Book Rosalie Edholm Scripps College Recommended Citation Edholm, Rosalie, "Portrait: A Graphic Novel and Artist's Book" (2010). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 24. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/24 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rosalie Edholm May 3 2010 Portrait: a Graphic Novel and Artists’ Book by Rosalie Edholm Submitted to Scripps College in partial fulfillment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Rankaitis Professor Maryatt December 9th, 2009 Updated Addendum: May 3, 2010 Rosalie Edholm May 3 2010 Portrait: A Graphic Novel and Artist’s Book At this exact moment, graphic novels are enjoying a heyday of popularity, profusion and attention. As the graphic novel medium matures and detaches itself from the “non-serious” reputation of comics, it is becoming clear that graphic novels are a powerful and effective art form, using the both verbal and the visual to relay their narratives. Portrait, the short graphic novel that is my senior art project, is intended to emphasize the artist’s book character of the graphic novel, and serve as an example of how a graphic novel’s artist’s book characteristics allow communication of the artist’s message effectively. Due to the present explosion of not just new graphic novels, but film adaptations and a wider readership, situating my own work as a graphic novel required looking into the differences between comics and other sequential art genres. -

Approaches to Teaching Bechdel's Fun Home

Approaches to Teaching Bechdel’s Fun Home Edited by Judith Kegan Gardiner The Modern Language Association of America New York 2018 MM7436-Gardiner.indb7436-Gardiner.indb iiiiii 99/5/18/5/18 111:511:51 AAMM © 2018 by The Modern Language Association of America All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America MLA and the MODERN LANGUAGE ASSOCIATION are trademarks owned by the Modern Language Association of America. For information about obtaining permission to reprint material from MLA book publications, send your request by mail (see address below) or e-mail ([email protected]). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Names: Gardiner, Judith Kegan, editor. Title: Approaches to teaching Bechdel’s Fun home / edited by Judith Kegan Gardiner. Description: New York : Modern Language Association of America, 2018. | Series: Approaches to teaching world literature, ISSN 1059-1133 ; 154 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: LCCN 2018026970 (print) | LCCN 2018044416 (ebook) ISBN 9781603293600 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781603293617 (Kindle) ISBN 9781603293587 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781603293594 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bechdel, Alison, 1960– Fun home. | Bechdel, Alison, 1960—Study and teaching. | Graphic novels—Study and teaching (Higher) Classifi cation: LCC PN6727.B3757 (ebook) | LCC PN6727.B3757 F863 2018 (print) | DDC 741.5/973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026970 Approaches to Teaching World Literature 154 ISSN 1059-1133 Cover illustration of the paperback and electronic