Approaches to Teaching Bechdel's Fun Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts & Humanities

Below is a list of titles to be reviewed in the August 2017 issue of Library Journal. These lists include pertinent publisher and bibliographic information for your convenience. Also included are titles recently reviewed as online-only Xpress Reviews. Starred reviews are indicated with **. Publishers: Please remember to send us one finished copy of each book that is scheduled for review (i.e., all of the forthcoming titles listed below) if you initially submitted a galley or bound manuscript. Our reviewers are not paid, and we like to send a finished copy of the reviewed book as a thank you. Materials should be mailed to: Library Journal, 123 William Street, Suite 802, New York, NY 10038. ARTS & HUMANITIES CRAFTS/DIY ART INSTRUCTION **Leamy, Selwyn. Read This If You Want To Be Great at Drawing. Laurence King. Oct. 2017. 128p. illus. ISBN 9781786270542. pap. $17.99. ART INSTRUCTION Schweiger, Rebecca. Release Your Creativity: Discover Your Inner Artist with 15 Simple Painting Projects. Sixth&Spring. May 2017. 144p. illus. index. ISBN 9781942021483. pap. $19.95. ART INSTRUCTION CRAFTS Lam, Isabella. Beautiful Beadweaving: Simply Gorgeous Jewelry. Kalmbach. Mar. 2017. 112p. illus. ISBN 9781627003018. pap. $22.99; ebk. ISBN 9781627004725. CRAFTS Moad, Elizabeth. Paper Quilling: All the Skills You Need To Make 20 Beautiful Projects. Search. Jun. 2017. 96p. illus. index. ISBN 9781782214250. pap. $15.95. CRAFTS DIY Kyler, Silas J. & David Hildreth. The Art and Craft of Wood: A Practical Guide to Harvesting, Choosing, Reclaiming, Preparing, Crafting, and Building with Raw Wood. Quarry: Quarto. Jun. 2017. 160p. illus. index. ISBN 9781631592973. $24.99. -

Fun Home: a Family

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic 0 | © 2020 Hope in Box www.hopeinabox.org About Hope in a Box Hope in a Box is a national 501(c)(3) nonprofit that helps rural educators ensure every LGBTQ+ student feels safe, welcome, and included at school. We donate “Hope in a Box”: boxes of curated books featuring LGBTQ+ characters, detailed curriculum for these books, and professional development and coaching for educators. We believe that, through literature, educators can dispel stereotypes and cultivate empathy. Hope in a Box has worked with hundreds of schools across the country and, ultimately, aims to support every rural school district in the United States. Acknowledgements Special thanks to this guide’s lead author, Dr. Zachary Harvat, a high school English teacher with a PhD focusing on 20th and 21st century English literature. Additional thanks to Sara Mortensen, Josh Thompson, Daniel Tartakovsky, Sidney Hirschman, Channing Smith, and Joe English. Suggested citation: Harvat, Zachary. Curriculum Guide for Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Hope in a Box, 2020. For questions or inquiries, email our team at [email protected]. Learn more on our website, www.hopeinabox.org. Terms of use Please note that, by viewing this guide, you agree to our terms and conditions. You are licensed by Hope in a Box, Inc. to use this curriculum guide for non- commercial, educational and personal purposes only. You may download and/or copy this guide for personal or professional use, provided the copies retain all applicable copyright and trademark notices. The license granted for these materials shall be effective until July 1, 2022, unless terminated sooner by Hope in a Box, Inc. -

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011

Emily Jones Independent Press Report Fall 2011 Table of Contents: Fact Sheet 3 Why I Chose Top Shelf 4 Interview with Chris Staros 5 Book Review: Blankets by Craig Thompson 12 2 Fact Sheet: Top Shelf Productions Web Address: www.topshelfcomix.com Founded: 1997 Founders: Brett Warnock & Chris Staros Editorial Office Production Office Chris Staros, Publisher Brett Warnock, Publisher Top Shelf Productions Top Shelf Productions PO Box 1282 PO Box 15125 Marietta GA 30061-1282 Portland OR 97293-5125 USA USA Distributed by: Diamond Book Distributors 1966 Greenspring Dr Ste 300 Timonium MD 21093 USA History: Top Shelf Productions was created in 1997 when friends Chris Staros and Brett Warnock decided to become publishing partners. Warnock had begun publishing an anthology titled Top Shelf in 1995. Staros had been working with cartoonists and had written an annual resource guide The Staros Report regarding the best comics in the industry. The two joined forces and shared a similar vision to advance comics and the graphic novel industry by promoting stories with powerful content meant to leave a lasting impression. Focus: Top Shelf publishes contemporary graphic novels and comics with compelling stories of literary quality from both emerging talent and known creators. They publish all-ages material including genre fiction, autobiographical and erotica. Recently they have launched two apps and begun to spread their production to digital copies as well. Activity: Around 15 to 20 books per year, around 40 titles including reprints. Submissions: Submissions can be sent via a URL link, or Xeroxed copies, sent with enough postage to be returned. -

Decoding the Visual Rhetoric: Memory and Trauma in Lynda Barry's One! Hundred! Demons!

http://wjel.sciedupress.com World Journal of English Language Vol. 8, No. 2; 2018 Decoding the Visual Rhetoric: Memory and Trauma in Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! Partha Bhattacharjee & Priyanka Tripathi Department of Humanties and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Patna, India. Correspondence: E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 2, 2018 Accepted: September 20, 2018 Online Published: September 23, 2018 doi:10.5430/wjel.v8n2p37 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v8n2p37 Abstract Memory is an important tool in Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! (2002) as she reconnoitres in non-linear fragments the personal trauma she faced while she was growing up. Layered into nineteen disjointed chapters, Barry’s graphic narrative is an amalgamation of images, collages and photographs, often following the pattern of a scrapbook style that justifies not only the events drawn in her narrative but also the motive of visual rhetoric in comics where visual images communicate and concretize meaning. Initially published as web comics (slate.com), each chapter consists of hand-painted vignettes of multifarious themes which are directly or indirectly linked to Barry’s life, covering from her childhood to adulthood. In the backdrop of these tools, techniques of visual rhetoric the objective of this paper is to investigate the form of the graphic narrative, the visual language employed in order to explore the traumatised childhood, memory and truth-telling in comics. Keywords: Trauma, Memory, Collage, Visual Language 1. Introduction Comics Studies emerges as a scholarly field in the second half of the 20th century and gains its boost to reach the acme in the current century. -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics Edited by Michelle Ann Abate, Karly Marie Grice, and Christine N. Stamper In examples ranging from Trina Robbins’s “Sandy Comes Out” in the first issue of Wimmen’s Comix (1972) and Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For series (1986 – 2005) to Diane DiMassa's Hothead Paisan (1991 – 1996) and the recent reboot of DC’s Batwoman (2006 - present), comics have been an important locus of lesbian identity, community, and politics for generations. Accordingly, this special issue will explore the intersection of lesbians and comics. What role have comics played in the cultural construction, social visibility, and political advocacy of same-sex female attraction and identity? Likewise, how have these features changed over time? What is the relationship between lesbian comics and queer comics? In what ways does lesbian identity differ from queer female identity in comics, and what role has the medium played in establishing this distinction as well as blurring, reinforcing, or policing it? Discussions of comics from all eras, countries, and styles are welcome. Likewise, we encourage examinations of comics from not simply literary, artistic, and visual perspectives, but from social, economic, educational, and political angles as well. Possible topics include, but are not limited to: Comics as a locus of representation for lesbian identity, community, and sexuality Analysis of titles featuring lesbian plots, characters, and themes, such as Ariel Schrag’s The High School Chronicles strips, -

Library Public Programming

Comics and Medicine: Access Points Public programming June 16th-17th, 2017 Seattle, WA All events are located on 1st and 4th floor levels of The Seattle Public Library, Central Location. Please make arrangements for ASL interpreting or other accommodation at least 7 calendar days in advance. Please contact [email protected] by June 9th, 2017. Friday, June 16th 9:00-10:00 Keynote Talk: Hillary Chute, “Comics and Psychic States: Access, Interiority, Circulation” Introduction by Susan M. Squier (Pennsylvania State University) Hillary Chute is the author of Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics (Columbia UP, 2010), Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists (University of Chicago Press, 2014), and Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Harvard University Press, 2016). She has also co-edited two journal special issues: Mfs: Modern Fiction Studies on “Graphic Narrative” (2006) and Critical Inquiry on “Comics & Media” (2014), and she is Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman’s MetaMaus (Pantheon, 2011). Main Auditorium (1st floor) 10:20-11:50 HEALTHCARE ACCESS/HEALTHCARE BARRIERS (Moderated by Michael Green) Main Auditorium (1st floor) “How to save a life: A graphic novella for Chinese speakers” Hendrika Meischke, PhD (University of Washington) "Covering healthcare in crisis: Comics journalism from a pop-up clinic” Meredith Li-Vollmer (Public Health - Seattle and King County) “The Experience of Disability: A Patient’s Perspective Through Historical Comics” Amy Wagner, PT, DPT, GCS (University of the -

LOCAS: the MAGGIE and HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study Guide Written by Art Baxter

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators STUDY GUIDE: LOCAS: THE MAGGIE AND HOPEY STORIES by Jaime Hernandez Study guide written by Art Baxter Introduction Comic books were in the midst of change by the early 1980s. The Marvel, DC and Archie lines were going through the same tired motions being produced by second and third generation artists and writers who grew up reading the same books they were now creating. Comic book specialty shops were growing in number and a new "non- returnable" distribution system had been created to supply them. This opened the door for publishers who had small print runs, with color covers and black and white interiors, to emerge with an alternative to corporate mainstream comics. These new comics were often a cross between the familiar genres of the mainstream and the personal artistic freedom of underground comics, but sometimes something altogether different would appear. In 1976, Harvey Pekar began self-publishing his annual autobiographical comics collection, American Splendor, with art by R. Crumb and others, from his home in Cleveland, Ohio. Other cartoonists self-published their mainstream- rejected comics, like Cerebus (Dave Sim, 1977) and Elfquest (Wendy & Richard Pini, 1978) to financial and critical success. With proto-graphic novel publisher, Eclipse, mainstream rebels produced explicit versions of their earlier work, such as Sabre (Don McGreggor & Paul Gulacy, 1978) and Stewart the Rat (Steve Gerber & Gene Colan, 1980). Underground comics evolved away from sex and drugs toward maturity in two anthologies, RAW (Art Spiegleman & Francoise Mouly, eds., 1980) and Weirdo (R. Crumb, ed., 1981). Under the Fantagraphics Books imprint, Gary Groth and Kim Thompson began to publish comics which aspired to an artistic quality that lived up to the high standard set forth in the pages of their critical magazine, The Comics Journal. -

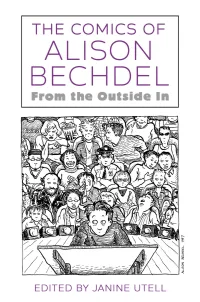

The Comics of Alison Bechdel from the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel From the Outside In Edited by Janine Utell University Press of Mississippi / Jackson CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX THE WORKS OF ALISON BECHDEL XI INTRODUCTION Serializing the Self in the Space between Life and Art JANINE UTELL XIII I. IN AND/OR OUT: QUEER THEORY, LESBIAN COMICS, AND THE MAINSTREAM THE HOSPITABLE AESTHETICS OF ALISON BECHDEL VANESSA LAUBER 3 “GIRLIE MAN, MANLY GIRL, IT’S ALL THE SAME TO ME” How Dykes to Watch Out For Shifted Gender and Comix ANNE N. THALHEIMER 22 DISSEMINATING QUEER THEORY Dykes to Watch Out For and the Transmission of Theoretical Thought KATHERINE PARKER-HAY 36 BECHDEL’S MEN AND MASCULINITY Gay Pedant and Lesbian Man JUDITH KEGAN GARDINER 52 VI CONTENTS MO VAN PELT Dykes to Watch Out For and Peanuts MICHELLE ANN ABATE 68 II. INTERIORS: FAMILY, SUBJECTIVITY, MEMORY DANCING WITH MEMORY IN FUN HOME ALISSA S. BOURBONNAIS 89 “IT BOTH IS AND ISN’T MY LIFE” Autobiography, Adaptation, and Emotion in Fun Home, the Musical LEAH ANDERST 105 GENERATIONAL TRAUMA AND THE CRISIS OF APRÈS-COUP IN ALISON BECHDEL’S GRAPHIC MEMOIRS NATALJA CHESTOPALOVA 119 THE EXPERIMENTAL INTERIORS OF ALISON BECHDEL’S ARE YOU MY MOTHER? YETTA HOWARD 135 INCHOATE KINSHIP Psychoanalytic Narrative and Queer Relationality in Are You My Mother? TYLER BRADWAY 148 III. PLACE, SPACE, AND COMMUNITY DECOLONIZING RURAL SPACE IN ALISON BECHDEL’S FUN HOME KATIE HOGAN 167 FUN HOME AND ARE YOU MY MOTHER? AS AUTOTOPOGRAPHY Queer Orientations and the Politics of Location KATHERINE KELP-STEBBINS 181 CONTENTS VII INSIDE THE ARCHIVES OF FUN HOME SUSAN R. -

Breaking Through Panels: Examining Growth and Trauma in Bechdel's Fun Home and Labelle's Assigned Male Comics

BREAKING THROUGH PANELS: EXAMINING GROWTH AND TRAUMA IN BECHDEL'S FUN HOME AND LABELLE'S ASSIGNED MALE COMICS Katelynn Phillips A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: William Albertini, Advisor Erin Labbie © 2018 Katelynn Phillips All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT William Albertini, advisor Comics featuring LGBTQ children have the burden of challenging cis/heteronormative versions of childhood. Such examples of childhood, according to author Katherine Bond Stockton, are false and restrict children to a vision of innocence that leaves no room for queer children to experience their own versions of childhood. Furthermore, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) community has taken a “progressive”-based approach to time, assuming that newer generations have avoided the trauma of the past because ideas about sexual orientation and gender have advanced with time. Newer generations of the LGBTQ community forget that many have struggled for change to occur, instead choosing to forget the wounds of the past. By analyzing two comic works—Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home and Sophie Labelle’s web comic series Assigned Male—I argue that we must let go of our suspicion towards LGBTQ child characters and open ourselves up to what can be learned from them. I also argue that both the past (with its wounds and trauma) and the future must be accepted into the present in order to give children the childhood they desire, rather than the childhood we recall. Both Fun Home and Assigned Male demonstrate that childhood is far from the simplistic happy time of life and can be just as fraught with complication as adulthood. -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose. -

History and Background

History and Background Book by Lisa Kron, music by Jeanine Tesori Based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel SYNOPSIS Both refreshingly honest and wildly innovative, Fun Home is based on Vermont author Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir. As the show unfolds, meet Bechdel at three different life stages as she grows and grapples with her uniquely dysfunctional family, her sexuality, and her father’s secrets. ABOUT THE WRITERS LISA KRON was born and raised in Michigan. She is the daughter of Ann, a former community activist, and Walter, a German-born lawyer and Holocaust survivor. Kron spent much of her childhood feeling like an outsider because of her religion and sexuality. She attended Kalamazoo College before moving to New York in 1984, where she found success as both an actress and playwright. Many of Kron’s plays draw upon her childhood experiences. She earned early praise for her autobiographical plays 2.5 Minute Ride and 101 Humiliating Stories. In 1989, Kron co-founded the OBIE Award-winning theater company The Five Lesbian Brothers, a troupe that used humor to produce work from a feminist and lesbian perspective. Her play Well, which she both wrote and starred in, opened on Broadway in 2006. Kron was nominated for the Best Actress in a Play Tony Award for her work. JEANINE TESORI is the most honored female composer in musical theatre history. Upon receiving her degree in music from Barnard College, she worked as a musical theatre conductor before venturing into the art of composing in her 30s. She made her Broadway debut in 1995 when she composed the dance music for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and found her first major success with the off- Broadway musical Violet (Obie Award, Lucille Lortel Award), which was later produced on Broadway in 2014.