History and Cultural Identity : Retrieving the Past, Shaping the Future / Edited by John P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civilization Studies 1

Civilization Studies 1 Civilization Studies Civilization studies provide an in-depth examination of the development and accomplishments of one of the world's great civilizations through direct encounters with significant and exemplary documents and monuments. These sequences complement the literary and philosophical study of texts central to the humanities sequences, as well as the study of synchronous social theories that shape basic questions in the social science sequences. Their approach stresses the grounding of events and ideas in historical context and the interplay of events, institutions, ideas, and cultural expressions in social change. The courses emphasize texts rather than surveys as a way of getting at the ideas, cultural patterns, and social pressures that frame the understanding of events and institutions within a civilization. And they seek to explore a civilization as an integrated entity, capable of developing and evolving meanings that inform the lives of its citizens. Unless otherwise specified, courses should be taken in sequence. Note the prerequisites, if any, included in the course description of each sequence. Some civilization sequences are two-quarter sequences; others are three- quarter sequences. Students may meet a two-quarter civilization requirement with two courses from a three- quarter sequence. Because civilization studies sequences offer an integrated, coherent approach to the study of a civilization, students cannot change sequences. Students can neither combine courses from a civilization sequence with a freestanding course nor combine various freestanding courses to create a civilization studies sequence. Students who wish to use such combinations are seldom granted approval to their petitions, including petitions from students with curricular and scheduling conflicts who have postponed meeting the civilization studies requirement until their third or fourth year in the College. -

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series C: Lnterreligious Activities

MS-603: Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum Collection, 1945-1992. Series C: lnterreligious Activities. 1952-1992 Box 43, Folder 8, Protestants and Israel, 1977-1978. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 (513) 221-1875 phone, (513) 221-7812 fax americanjewisharchives.org >--- -- ------- 3une 29, 1977 Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum Rabbi A. James Rudin \ . ~The 189th General Assembly (1977) of the United Presby terian Church in the USA calls upon the United States Government to reaffirm its support for the concept of Palestinian self determin.ation and to encourage the Arab states with PLO partici pation, to seek means for Palestininn participation in negotia tions in a manner consistent with the principles of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. '' \\ The following paragraph was deleted,to seek means to in· elude the PLO as the currently acknowledged spokespersons of the Pale,stinians, devising means to include the FLO in the ne gotiations.•• The vote was approximately 75% to 25% in favor of the substitute motion. It uas the only minority report accepted by the General Assembly. Rev. John Craig of Houston noted that "secure and recog• nized boundaries for Israel" is a critical issue and Rev. Donald Hyer of Michigan declared that "the Church mce-·'r''!.. Baptize the PLO." Rev. Linda Harter said the Church ~~ ~ engage in "directive politics' and that its "effectiveness in reconciliation would be ~dermined by the original paragraph 2-c. AJR:FM \ ANll l>l I i\MAllvN I LAl..olll 1,.)1 ll NAI ll'Rl 111 US L x an~lun Av•, i°ll<wYurk NY llHlJ(i Ml lrtoy l1 11l <1 /-1-0ll Lynne lanmello Director, />ublrc Rclat1on8 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New York, NY. -

Architectural Theory and Practice, and the Question of Phenomenology

Architectural Theory and Practice, and the Question of Phenomenology (The Contribution of Tadao Ando to the Phenomenological Discourse) Von der Fakultät Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen und Stadtplanung der Brandenburgischen Technischen Universität Cottbus zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Mohammadreza Shirazi aus Tabriz, Iran Gutachter: : Prof. Dr. Eduard Führ Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Karsten Harries Gutachter: Gastprofessor. Dr. Riklef Rambow Tag der Verteidigung: 02. Juni 2009 Acknowledgment My first words of gratitude go to my supervisor Prof. Führ for giving me direction and support. He fully supported me during my research, and created a welcoming and inspiring atmosphere in which I had the pleasure of writing this dissertation. I am indepted to his teachings and instructions in more ways than I can state here. I am particularly grateful to Prof. Karsten Harries. His texts taught me how to think on architecture deeply, how to challenge whatever is ‘taken for granted’ and ‘remain on the way, in search of home’. I am also grateful to other colleagues in L.S. Theorie der Architektur. I want to express my thanks to Dr. Riklef Rambow who considered my ideas and texts deeply and helped me with his advice at different stages. I am thankful for the comments and kind helps I received from Dr. Katharina Fleischmann. I also want to thank Prof. Hahn from TU Dresden and other PhD students who attended in Doktorandentag meetings and criticized my presentations. I would like to express my appreciation to the staff of Langen Foundation Museum for their kind helps during my visit of that complex, and to Mr. -

Cultural History in Spain History of Culture and Cultural History: Same Paths and Outcomes?*

Cultural History in Spain History of Culture and Cultural History: same paths and outcomes?* CAROLINA RODRÍGUEZ-LÓPEZ An overview &XOWXUDOKLVWRU\LVFXUUHQWO\DERRPLQJWRSLFLQ6SDLQ&XOWXUDOKLVWRU\LVQRZ ÁRXULVKLQJ DQG FHUWDLQ DUHDV KDYH GLVWLQJXLVKHG WKHPVHOYHV DV DXWRQRPRXV ÀHOGVRIVWXG\WKHKLVWRU\RIFXOWXUDOSROLWLFVUHDGLQJDQGSULQWLQJDQGPHGLFDO FXOWXUDOSUDFWLFHVIRUH[DPSOH+RZHYHUZKDWLVGHÀQHGDVcultural history in FXUUHQW6SDQLVKKLVWRULRJUDSK\LVQRWDQHDV\LVVXH/LNHWKHUHVWRI(XURSHDQ HYHQ$PHULFDQ KLVWRULRJUDSKLHV6SDQLVKKLVWRULRJUDSK\KDVJRQHWKURXJKDQ H[WHQVLYHDQGLQWHUHVWLQJSURFHVVVKLIWLQJIURPVRFLDOWRFXOWXUDOKLVWRU\7KH SURFHVV KDV QRW EHHQ H[HPSW IURP SUREOHPV DQG PLVXQGHUVWDQGLQJV DQG KDV GHWHUPLQHGQRWRQO\WKHZD\VLQZKLFKFXOWXUDOKLVWRU\KDVWUDGLWLRQDOO\ÁRZHG EXWDOVRWKHNLQGVRIUHVHDUFKDQGVFLHQWLÀFZRUNVWKDWKDYHEHHQODEHOHGZLWK the cultural history title. 7KLVFKDSWHURIIHUVDEULHIRYHUYLHZRIZKDW,KDYHMXVWPHQWLRQHGDERYH ,QRUGHUWRGRVRLWLVGLYLGHGLQWRWKUHHVHFWLRQV7KHÀUVWRQHGHDOVZLWKWKH KLVWRULFDODQGKLVWRULRJUDSKLFDOFRQWH[WVZKHQWKHÀUVWUHVHDUFKDQGGHEDWHVLQ 6SDLQIRFXVHGRQFXOWXUDOKLVWRU\,QWKHVHFRQGVHFWLRQ,LQWURGXFHWKHUHVHDUFK JURXSVLQVWLWXWLRQVDFDGHPLFSURJUDPVDQGSXEOLVKLQJKRXVHSURMHFWVWKDWKDYH HQFRXUDJHG DQG DUH FXUUHQWO\ RUJDQL]LQJ 6SDQLVK FXOWXUDO KLVWRU\ NQRZOHGJH DQGSURGXFWLRQ$QGODVWEXWQRWOHDVW,SUHVHQWDÀUVWDQGWHQWDWLYHOLVWRIH[DFW- ,DPJUDWHIXOWR(OHQD+HUQiQGH]6DQGRLFDIRUGHWDLOHGVXJJHVWLRQVDQGWR3DWULFLD %HUDVDOXFHDQG(OLVDEHWK.OHLQIRUDFFXUDWHUHDGLQJRIWKLVFKDSWHUάVÀUVWYHUVLRQ 211 Carolina Rodríguez-López O\ZKDW6SDQLVKKLVWRULDQVKDYHZULWWHQRQWKHÀHOGRIFXOWXUDOKLVWRU\,QRWKHU -

The Function of Reason in Hume and Consequences for the Classical

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 If Reason Is Not Sovereign: The Function of Reason in Hume and Consequences for the Classical/Positivist Divide, Rational Choice Theory, Low Self-Control Theory, and the Criminal Propensity Construct Michael Jason Kissner Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE IF REASON IS NOT SOVEREIGN: THE FUNCTION OF REASON IN HUME AND CONSEQUENCES FOR THE CLASSICAL/POSITIVIST DIVIDE, RATIONAL CHOICE THEORY, LOW SELF-CONTROL THEORY, AND THE CRIMINAL PROPENSITY CONSTRUCT By MICHAEL JASON KISSNER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Michael Jason Kissner defended on November 10, 2004. _______________________ Daniel Maier-Katkin Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________ Barney Twiss Outside Committee Member _______________________ Cecil Greek Committee Member Approved: __________________________ Thomas Blomberg, Dean, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................Page -

ESJOA Spring 2011

Volume 6 Issue 1 C.S.U.D.H. ELECTRONIC STUDENT JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGY Spring 2011 V O L U M E 6 ( 1 ) : S P R I N G 2 0 1 1 California State University Dominguez Hills Electronic Student Journal of Anthropology Editor In Chief Review Staff Scott Bigney Celso Jaquez Jessica Williams Maggie Slater Alex Salazar 2004 CSU Dominguez Hills Anthropology Club 1000 E Victoria Street, Carson CA 90747 Phone 310.243.3514 • Email [email protected] I Table of Contents THEORY CORNER Essay: Functionalism in Anthropological Theory By: Julie Wennstrom pp. 1-6 Abstract: Franz Boas, “Methods of Ethnology” By: Maggie Slater pp. 7 Abstract: Marvin Harris “Anthropology and the Theoretical and Paradigmatic Significance of the Collapse of Soviet and East European Communism By: Samantha Glover pp. 8 Abstract: Eleanor Burke Leacock “Women’s Status In Egalitarian Society: Implications For Social Evolution” By: Jessica Williams pp. 9 STUDENT RESEARCH Chinchorro Culture By: Kassie Sugimoto pp. 10-22 Reconstructing Ritual Change at Preceramic Asana By: Dylan Myers pp. 23-33 The Kogi (Kaggaba) of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and the Kotosh Religious Tradition: Ethnographic Analysis of Religious Specialists and Religious Architecture of a Contemporary Indigenous Culture and Comparison to Three Preceramic Central Andean Highland Sites By: Celso Jaquez pp. 34-59 The Early Formative in Ecuador: The Curious Site of Real Alto By: Ana Cuellar pp. 60-70 II Ecstatic Shamanism or Canonist Religious Ideology? By: Samantha Glover pp. 71-83 Wari Plazas: An analysis of Proxemics and the Role of Public Ceremony By: Audrey Dollar pp. -

My Name Is Bert Silver

Soviet Jewry Memories Bert Silver 2009 My name is Bert Silver. I was born on June 30, 1931, in Scranton, Pennsylvania, a community of 140,000 people of whom about 5,000 were Jews. I lived in Scranton until I left to attend Penn State University in 1949. After college I was drafted into the army and for all intents and purposes never returned to Scranton to live. After the army I went to the University of Minnesota to get a master’s degree. I then worked for the State of New York in Albany. After getting married Nancy and I lived in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania where I worked for the state. We moved to Washington in June 1961, when I was offered a job with the Department of Labor of the Federal government. We first lived in an apartment in Adelphi, Maryland. In 1962 we bought a house in Wheaton, Maryland, and in 1973, we moved to our present home in Potomac, Maryland. We joined B’nai Israel Congregation when our first son was old enough to attend Hebrew School and have been members since. At the time we joined the synagogue was still located on 16th and Crittenden Streets but had a Hebrew school building on Georgia Avenue in Wheaton. B'nai Israel is of course now located in Rockville, Maryland. I don’t remember exactly when I became involved in the Soviet Jewry movement but it was probably in 1969. I first got involved with the Washington Committee for Soviet Jewry (WCSJ), but I am not sure exactly how. -

Cultural Theorizing Has Dramatically Increased

Cultural CHAPTER 9 Theorizing Another Embarassing Confession Like the concept of social structure, the conceptualization of culture in sociology is rather vague, despite a great deal of attention by sociologists to the properties and dynamics of cul- ture. There has always been the recognition that culture is attached to social structures, and vice versa, with the result that sociologists often speak in terms of sociocultural formations or sociocultural systems and structures. This merging of structure and culture rarely clarifies but, instead, further conflates a precise definition of culture. And so, sociology’s big idea— culture—is much like the notion of social structure. Its conceptualization is somewhat meta- phorical, often rather imprecise, and yet highly evocative. There is no consensus in defini- tions of culture beyond the general idea that humans create symbol systems, built from our linguistic capacities, which are used to regulate conduct. And even this definition would be challenged by some. Since the 1980s and accelerating with each decade, the amount of cultural theorizing has dramatically increased. Mid-twentieth-century functional theory had emphasized the importance of culture but not in a context-specific or robust manner; rather, functional- ism viewed culture as a mechanism by which actions are controlled and regulated,1 whereas much of the modern revival of culture has viewed culture in a much more robust and inclusive manner. When conflict theory finally pushed functionalism from center stage, it also tended to bring forth a more Marxian view of culture as a “superstructure” generated by economic substructures. Culture became the sidekick, much like Tonto for the Lone Ranger, to social structure, with the result that its autonomy and force indepen- dent of social structures were not emphasized and, in some cases, not even recognized. -

Spiritual Heroes Rabbi Sid Schwarz Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation, Bethesda, MD Kol Nidre Sermon-October 11, 2016

Spiritual Heroes Rabbi Sid Schwarz Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation, Bethesda, MD Kol Nidre Sermon-October 11, 2016 For many years, the organization that I led-PANIM- ran 4-day seminars on Jewish values and social activism for teens who came to Washington D.C. from around the country. When I would speak to the students, my lead-off question would be: Who are your spiritual heroes? It was a question that gave pause. Most American teens would have fairly quick answers if I asked them to name their favorite lead singer in a band. Or their favorite movie star. Or their go-to sports legend. Each of those answers could have come back affixed with the label “hero”. But “spiritual hero” was not a word combination that they expected. I’d wait a minute or two and usually a few hands would go up in the air. Before I called on them I offered a definition so as to make it possible for more students to get a person in their mind’s eye. My definition: “A spiritual hero is someone, either living or deceased who, by virtue of their words and/or deeds, led a life that inspired others and was worthy of emulation.” Let me take a moment now and ask you to think of one person who has served for you as a spiritual hero. I hope most of you have thought of someone. If not, don’t worry. This sermon might give you some ideas. Tomorrow, during the afternoon break discussion, we will have a chance to share thoughts with one another. -

Imagination: a Philosophical Examination of The

1 The ‘Reality Oriented’ Imagination: a Philosophical Examination of the Imagination in ‘Mentalization’ and ‘Neuropsychoanalysis’. Annie Hardy Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London 2017 2 I, Annie Hardy, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the conceptualization of the imagination in contemporary psychoanalytic theory, focusing in particular on its connection with knowledge. I will propose that imaginative processes form the core of psychic ‘health’ by instantiating a state of mind in which the subject is genuinely open to ‘learning from experience’. At the centre of the investigation is a psychic process that I term the ‘reality oriented’ imagination: a form of conscious mental activity that facilitates an epistemological connection with both the internal and external worlds and renders the unobservable psychological experiences of others accessible. The concept of the ’reality oriented’ imagination significantly disrupts Freud’s portrayal of the imaginative processes as a form of wish-fulfilment in which the individual’s attention is drawn away from external reality and placed under the sway of the pleasure principle. Such differing presentations of the imagination across psychoanalytic models can arguably be understood by considering several major shifts in psychoanalytic theorizing since Freud’s time. I will propose that these changes can be characterised as an ‘epistemic turn’: a general movement in psychoanalysis towards framing the internal world as strategic rather than compensatory, and a corresponding understanding of psychopathological processes as a response to failures in understanding and prediction rather than instinctual conflict. -

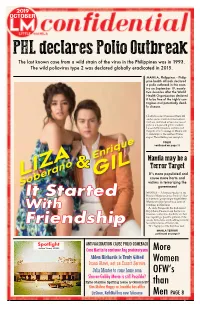

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman