Archaeologist Volume 58 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio History Lesson 1

http://www.touring-ohio.com/ohio-history.html http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/category.php?c=PH http://www.oplin.org/famousohioans/indians/links.html Benchmark • Describe the cultural patterns that are visible in North America today as a result of exploration, colonization & conflict Grade Level Indicator • Describe, the earliest settlements in Ohio including those of prehistoric peoples The students will be able to recognize and describe characteristics of the earliest settlers Assessment Lesson 2 Choose 2 of the 6 prehistoric groups (Paleo-indians, Archaic, Adena, Hopewell, Fort Ancients, Whittlesey). Give two examples of how these groups were similar and two examples of how these groups were different. Provide evidence from the text to support your answer. Bering Strait Stone Age Shawnee Paleo-Indian People Catfish •Pre-Clovis Culture Cave Art •Clovis Culture •Plano Culture Paleo-Indian People • First to come to North America • “Paleo” means “Ancient” • Paleo-Indians • Hunted huge wild animals for food • Gathered seeds, nuts and roots. • Used bone needles to sew animal hides • Used flint to make tools and weapons • Left after the Ice Age-disappeared from Ohio Archaic People Archaic People • Early/Middle Archaic Period • Late Archaic Period • Glacial Kame/Red Ocher Cultures Archaic People • Archaic means very old (2nd Ohio group) • Stone tools to chop down trees • Canoes from dugout trees • Archaic Indians were hunters: deer, wild turkeys, bears, ducks and geese • Antlers to hunt • All parts of the animal were used • Nets to fish -

Visualizing Paleoindian and Archaic Mobility in the Ohio

VISUALIZING PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC MOBILITY IN THE OHIO REGION OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amanda N. Colucci May 2017 ©Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation written by Amanda N. Colucci B.A., Western State Colorado University, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Mark Seeman, Ph.D., Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Eric Shook, Ph.D., Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. James Tyner, Ph.D. Dr. Richard Meindl, Ph.D. Dr. Alison Smith, Ph.D. Accepted by Dr. Scott Sheridan, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Geography Dr. James Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ……………………………………………………………………………..……...……. III LIST OF FIGURES ….………………………………………......………………………………..…….…..………iv LIST OF TABLES ……………………………………………………………….……………..……………………x ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..………………………….……………………………..…………….………..………xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 STUDY AREA AND TIMEFRAME ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1.1 Paleoindian Period ............................................................................................................................... -

Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-16-2019 Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site Silas Levi Chapman Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, Silas Levi, "Understanding Community: Microwear Analysis of Blades at the Mound House Site" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1118. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1118 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING COMMUNITY: MICROWEAR ANALYSIS OF BLADES AT THE MOUND HOUSE SITE SILAS LEVI CHAPMAN 89 Pages Understanding Middle Woodland period sites has been of considerable interest for North American archaeologists since early on in the discipline. Various Middle Woodland period (50 BCE-400CE) cultures participated in shared ideas and behaviors, such as constructing mounds and earthworks and importing exotic materials to make objects for ceremony and for interring with the dead. These shared behaviors and ideas are termed by archaeologists as “Hopewell”. The Mound House site is a floodplain mound group thought to have served as a “ritual aggregation center”, a place for the dispersed Middle Woodland communities to congregate at certain times of year to reinforce their shared identity. Mound House is located in the Lower Illinois River valley within the floodplain of the Illinois River, where there is a concentration of Middle Woodland sites and activity. -

A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee

From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Miller, Darcy Shane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 09:33:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/320030 From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee by Darcy Shane Miller __________________________ Copyright © Darcy Shane Miller 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Darcy Shane Miller, titled From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Vance T. Holliday _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Steven L. Kuhn _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Mary C. Stiner _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) David G. Anderson Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Motion for Leave to Supplement Replies to USEC and the NRC Staff by Geoffrey Sea

I lOLH UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DOCKETED NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION USNRC August 17, 2005 (1:01pm) ATOMIC SAFETY AND LICENSING BOARD OFFICE OF SECRETARY Before the Administrative Law Judges: RULEMAKINGS AND Lawrence G. McDade, Chairman ADJUDICATIONS STAFF Paul B. Abramson Richard E. Wardwell ) Filed August 17, 2005 In the Matter of ) ) USEC Inc. ) Docket No. 70-7004 (American Centrifuge Plant) ) -) Motion for Leave to Supplement Replies to USEC and the NRC Staff by Geoffrey Sea Petitioner Geoffrey Sea asks leave to supplement his replies to the Answers of USEC and NRC Staff, which were filed on March 23, 2005, and March 25, 2005, respectively. Original replies to the Answers were filed by the Petitioner on March 30, 2005, and April 1, 2005, respectively. The reason for supplementation is new information that is detailed in Petitioners Amended Contentions, being filed concurrently. This new information includes a declaration by three cultural resource experts who completed a visit to the GCEP Water Field site on August 5, 2005. The experts identified a man- made earthwork on the site, crossed by well-heads, just as Petitioner has claimed in prior filings. 7eIPLALTC-= <3 - 31.E The new information also includes two parts in a series of articles by Spencer Jakab about USEC's dismal economic prospects, the second published only yesterday, August 15, 2005. It also includes new statements by Bill Murphie, field office manager for DOE with jurisdiction over Piketon, about USEC's unwillingness to reimburse the government for improper expenses identified in a report by the DOE Office of Inspector General, and about the possibility that DOE may seek to recover these costs. -

The Bulletin Number 36 1966

The Bulletin Number 36 1966 Contents The Earliest Occupants – Paleo-Indian hunters: a Review 2 Louis A. Brennan The Archaic or Hunting, Fishing, Gathering Stage: A Review 5 Don W. Dragoo The Woodland Stage: A Review 9 W. Fred Kinsey The Owasco and Iroquois Cultures: a Review 11 Marian E. White The Archaeology of New York State: A Summary Review 14 Louis A. Brennan The Significance of Three Radiocarbon Dates from the Sylvan Lake Rockshelter 18 Robert E. Funk 2 THE BULLETIN A SYMPOSIUM OF REVIEWS THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF NEW YORK STATE by William A. Ritchie. The American Museum of Natural History-The Natural History Press, Garden City, New York. 1965. XXI 357 pp. 12 figures, 113 plates. $12. 50 The following five papers comprise The Bulletin's effort to do justice to what will undoubtedly be regarded for the coming decade at least as the basic and standard reference on Northeastern regional prehistory. The reviews are by chronological-cultural era, the fluted point Paleo-hunter period, the Archaic, the Early and Middle Woodland, and the Owasco into Iroquois Late Woodland. These are followed by a summary review. The editor had John Witthoft's agreement to review the Paleo-hunter section of the book, but no review had been received by press time. Witthoft's review will be printed if and when received. In order not to lead off the symposium with a pass, the editor has stepped in as a substitute. THE EARLIEST OCCUPANTS-PALEO-INDIAN HUNTERS A REVIEW Louis A. Brennan Briarcliff College Center The distribution of finds of Paleo-hunter fluted points, as plotted in Fig. -

Transmission of Cultural Variants in the North American Paleolithic 9

Transmission of Cultural Variants in the North American Paleolithic 9 Michael J. O’Brien, Briggs Buchanan, Matthew T. Boulanger, Alex Mesoudi, Mark Collard, Metin I. Eren, R. Alexander Bentley, and R. Lee Lyman Abstract North American fluted stone projectile points occur over a relatively short time span, ca. 13,300–11,900 calBP, referred to as the Early Paleoindian period. One long-standing topic in Paleoindian archaeology is whether variation in the points is the result of drift or adaptation to regional environments. Studies have returned apparently conflicting results, but closer inspection shows that the results are not in conflict. At one scale—the overall pattern of flake removal—there appears to have been an early continent-wide mode of point manufacture, but at another scale—projectile-point shape—there appears to have been regional adaptive differences. In terms of learning models, the Early Paleoindian period appears to have been characterized by a mix of indirect-bias learning at the continent- wide level and guided variation at the regional level, the latter a result of continued experimentation with hafting elements and other point characters to match the changing regional environments. Close examination of character-state changes allows a glimpse into how Paleoindian knappers negotiated the design landscape in terms of character-state optimality of their stone weaponry. Keywords Clovis • Cultural transmission • Fluted point • Guided variation • Paleolithic • Social learning M.J. O’Brien () • M.T. Boulanger • M.I. Eren • R.L. Lyman 9.1 Introduction Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA Cultural-transmission theory has as its purpose the identi- e-mail: [email protected] fication, description, and explanation of mechanisms that B. -

2013 ESAF ESAF Business Office, P.O

BULLETIN of the EASTERN STATES ARCHEOLOGICAL FEDERATION NUMBER 72 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ANNUAL ESAF MEETING 79th Annual Meeting October 25-28, 2012 Perrysburg, OH Editor Roger Moeller TABLE OF CONTENTS ESAF Officers............................................................................ 1 Minutes of the Annual ESAF Meeting...................................... 2 Minutes of the ESAF General Business Meeting ..................... 7 Webmaster's Report................................................................... 10 Editor's Report........................................................................... 11 Brennan Award Report............................................................... 12 Treasurer’s Report..................................................................... 13 State Society Reports................................................................. 14 Abstracts.................................................................................... 19 ESAF Member State Society Directories ................................. 33 ESAF OFFICERS 2012/2014 President Amanda Valko [email protected] President-Elect Kurt Carr [email protected] Past President Dean Knight [email protected] Corresponding Secretary Martha Potter Otto [email protected] Recording Secretary Faye L. Stocum [email protected] Treasurer Timothy J. Abel [email protected] Business Manager Roger Moeller [email protected] Archaeology of Eastern North America -

A North American Perspective on the Volg (PDF)

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint A North American perspective on the Volgu Biface Cache from Upper Paleolithic France and its relationship to the “Solutrean Hypothesis” for Clovis origins J. David Kilby Department of Anthropology, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The “Solutrean hypothesis” for the origins of the North American Clovis Culture posits that early North American Volgu colonizers were direct descendants of European populations that migrated across the North Atlantic during the Clovis European Upper Paleolithic. The evidential basis for this model rests largely on proposed technological and Solutrean behavioral similarities shared by the North American Clovis archaeological culture and the French and Iberian Cache Solutrean archaeological culture. The caching of stone tools by both cultures is one of the specific behavioral correlates put forth by proponents in support of the hypothesis. While more than two dozen Clovis caches have been identified, Volgu is the only Solutrean cache identified at this time. Volgu consists of at least 15 exquisitely manufactured bifacial stone tools interpreted as an artifact cache or ritual deposit, and the artifacts themselves have long been considered exemplary of the most refined Solutrean bifacial technology. This paper reports the results of applying methods developed for the comparative analysis of the relatively more abundant caches of Clovis materials in North America to this apparently singular Solutrean cache. In addition to providing a window into Solutrean technology and perhaps into Upper Paleolithic ritual behavior, this comparison of Clovis and Solutrean assemblages serves to test one of the tangible archaeological implications of the “Solutrean hypoth- esis” by evaluating the technological and behavioral equivalence of Solutrean and Clovis artifact caching. -

Discover Illinois Archaeology

Discover Illinois Archaeology ILLINOIS ASSOCIATION FOR ADVANCEMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY Discover Illinois Archaeology Illinois’ rich cultural heritage began more collaborative effort by 18 archaeologists from than 12,000 years ago with the arrival of the across the state, with a major contribution by ancestors of today’s Native Americans. We learn Design Editor Kelvin Sampson. Along with sum- about them through investigations of the remains maries of each cultural period and highlights of they left behind, which range from monumental regional archaeological research, we include a earthworks with large river-valley settlements to short list of internet and print resources. A more a fragment of an ancient stone tool. After the extensive reading list can be found at the Illinois arrival of European explorers in the late 1600s, a Association for Advancement of Archaeology succession of diverse settlers added to our cul- web site www.museum.state.il.us/iaaa/DIA.pdf. tural heritage, leading to our modern urban com- We hope that by reading this summary of munities and the landscape we see today. Ar- Illinois archaeology, visiting a nearby archaeo- chaeological studies allow us to reconstruct past logical site or museum exhibit, and participating environments and ways of life, study the rela- in Illinois Archaeology Awareness Month pro- tionship between people of various cultures, and grams each September, you will become actively investigate how and why cultures rise and fall. engaged in Illinois’ diverse past and DISCOVER DISCOVER ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY, ILLINOIS ARCHAEOLOGY. summarizing Illinois culture history, is truly a Alice Berkson Michael D. Wiant IIILLINOIS AAASSOCIATION FOR CONTENTS AAADVANCEMENT OF INTRODUCTION. -

Olde New Mexico

Olde New Mexico Olde New Mexico By Robert D. Morritt Olde New Mexico, by Robert D. Morritt This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Robert D. Morritt All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2709-6, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2709-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................... vii Preface........................................................................................................ ix Sources ....................................................................................................... xi The Clovis Culture ...................................................................................... 1 Timeline of New Mexico History................................................................ 5 Pueblo People.............................................................................................. 7 Coronado ................................................................................................... 11 Early El Paso ............................................................................................ -

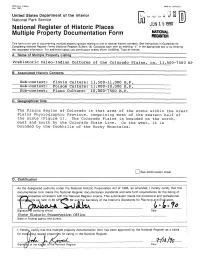

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and.