Pattern, Ritual and Thresholds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Ceramics Monthly Nov83 Cei11

William C. Hunt ........................................ Editor Barbara Tipton ...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager ........................ Art Director Ruth C. Butler.............................. Copy Editor Valentina Rojo....................... Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley.............. Circulation Manager Connie Belcher ... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.................................. Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S. L. Davis, Pres.; P. S. Emery, Sec.: 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year SI 6, two years $30, three years $40. Add $5 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine wrapper label and your new address to Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Office, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, texts and news releases dealing with ceramic art are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet describing procedures for the preparation and submission of a man uscript is available upon request. Send man uscripts and correspondence about them to The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Indexing:Articles in each issue of Ceramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index. A 20-year subject index (1953-1972) covering Ceramics Monthly feature articles, Sugges tions and Questions columns is available for $1.50, postpaid from the Ceramics Monthly Book Department, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Additionally, each year’s arti cles are indexed in the December issue. -

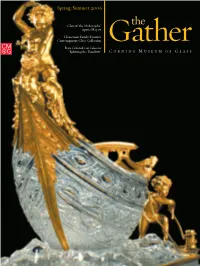

Gather Newsletter.Indd

Spring/Summer 2006 “Glass of the Maharajahs” the opens May 19 Heineman Family Donates Contemporary Glass Collection Rare Colored Cut Glass in Gather “Splitting the Rainbow” C o r n i n g M u s e u m o f G l a s s DIRECTOR’S LETTER Museum News One of the pleasures of working at The Corning Museum of Glass is the fact that the Museum never stands still. We are ambitious, and Corning Incorporated and our other supporters allow us— within reason—to turn many of our dreams into reality. Online Database Details Glass Exhibitions Worldwide New Museum Publication and Video Available Contemporary glass is a vital part of our collection and exhibitions. A new online database, compiled and maintained by the Rakow We were thrilled, therefore, at the beginning of the year, to receive Research Library, offers web users the ability to search for past, A new publication from The the largest gift of contemporary glass in the Museum’s history. present and upcoming temporary glass exhibitions around the Corning Museum of Glass Photo by Frank J. Borkowski. world. The Worldwide Glass Exhibition Database can be found at explores the past 25 years of www.cmog.org/exhibitionsdatabase. contemporary glass, and a new Ben Heineman Sr. and his wife Natalie have spent more than 20 years building video produced by The Studio one of the most distinguished private collections of contemporary glass, and have “The Rakow’s mission is to collect, maintain and provide public introduces glass students to the collected with a consummate sense of what is best among the countless works access to all glass-related resources," says Diane Dolbashian, art of flameworking. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

BETTY WOODMAN Born In1930, Norwalk, CT Died in 2018, New

BETTY WOODMAN Born in1930, Norwalk, CT Died in 2018, New York, NY Lived and worked in New York, NY and Antella, Italy EDUCATION 1950 Alfred University, The School for American Craftsmen, Alfred, New York, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Shadows and Silhouettes, David Kordansky, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Recent Works, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill, Rome, Italy Florentine Interiors, Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, Austria 2016 Breakfast At The Seashore Lunch In Antella, Salon 94 Bowery, New York, NY Theatre of the Domestic, ICA, London, UK 2015 Betty Woodman, curated by Vincenzo De Bellis, Museo Marino Marini, Florence, Italy Betty Woodman, Mendes Wood, São Paulo, Brazil Illusions of Domesticity, David Kordansky, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Interior Views, Galerie Francesca Pia, Zurich, Switzerland 2013 CONTRO VERSIES CONTRO VERSIA, an inaccurate history of painting and ceramics, Gallery Diet, Miami, FL Of Botticelli, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, Germany Windows, Carpets and Other Paintings, Salon 94 Freemans, New York, NY 2012 Betty Woodman, David Klein Gallery, Birmingham, MI 2011 Roman Fresco / Pleasures and Places, Salon 94 Bowery, New York, NY Betty Woodman: Front/Back, Salon 94, New York, NY Betty Woodman: Places, Spaces & Things, Gardiner Museum, Toronto, Canada 2010 Three Kilns Occupied by Three Pieces, Tuscia Electa Arte Contemporanea, Impruneta, Italy Betty Woodman: Roman Fresco/Pleasures and Places, American Academy in Rome, Rome, Italy Betty Woodman: Ceramics and Works on Paper, Harvey Meadows Gallery, Aspen, CO Anderson Ranch Art Center, -

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad. -

Craft Horizons JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1969 $2.00 Potteraipiney Wheel S & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT I

craft horizons JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1969 $2.00 PotterAipiney Wheel s & CERAMIC EQUIPMENT i Operating from one of the most modern facilities of its kind, A. D. Alpine, Inc. has specialized for more than a quarter of a century in the design and manufac- ture of gas and electric kilns, pottery wheels, and a complete line of ceramic equipment. Alpine supplies professional potters, schools, and institutions, throughout the entire United States. We manufacture forty-eight different models of high fire gas and electric kilns. In pottery wheels we have designed an electronically controlled model with vari- able speed and constant torque, but we still manufacture the old "KICK WHEEL" too. ûzùzêog awziözbfe Also available free of charge is our book- let "Planning a Ceramic Studio or an In- stitutional Ceramic Arts Department." WRITE TODAY Dept. A 353 CORAL CIRCLE EL SEGUNDO, CALIF. 90245 AREA CODE (213) 322-2430 772-2SS7 772-2558 horizons crafJanuary/February 196t9 Vol. XXIX No. 1 4 The Craftsman's World 6 Letters 7 Our Contributors 8 Books 10 Three Austrians and the New Jersey Turnpike by Israel Horovitz 14 The Plastics of Architecture by William Gordy 18 The Plastics of Sculpture: Materials and Techniques by Nicholas Roukes 20 Freda Koblick by Nell Znamierowski 22 Reflections on the Machine by John Lahr 26 The New Generation of Ceramic Artists by Erik Gronborg 30 25th Ceramic National by Jean Delius 36 Exhibitions 53 Calendar 54 Where to Show The Cover: "Phenomena Phoenix Run," polyester resin window by Paul Jenkins, 84" x 36", in the "PLASTIC as Plastic" show at New York's Museum of Contemporary Crafts (November 22-Januaiy 12). -

2011 Honor Roll

The 2011 Archie Bray p Alexander C. & Tillie S. Andrew Martin p Margaret S. Davis & Mary Roettger p Barbara & David Beumee Park Avenue Bakery Jane M Shellenbarger p Ann Brodsky & Bob Ream Greg Jahn & Nancy Halter p Denise Melton $1,000 to $4,999 Charles Hindes Matching Gift 2011 From the Center p p p p Honor Roll shows Ted Adler p Dwight Holland Speyer Foundation Mathew McConnell Bruce Ennis Janet Rosen Nicholas Bivins Alex Kraft Harlan & William Shropshire Amy Budke Janice Jakielski Melissa Mencini Organizations to the Edge: 60 Years cumulative gifts of cash, Allegra Marketing Ayumi Horie & Chris & Kate Staley p Karl McDade p Linda M. Deola, Esq, Diane Rosenmiller & Mark Boguski p Marian Kumner Kayte Simpson Lawrence Burde Erin Jensen Forrest Merrill Organizations matching of Creativity and securities & in-kind Print & Web Robin Whitlock p Richard & Penny Swanson pp Bruce R. & Judy Meadows Morrison, Motl & Sherwood Nicholas Seidner pp Fay & Phelan Bright Jay Lacouture p Gay Smith p Scott & Mary Buswell Michael Johnson Sam Miller employee gifts to the Innovation at the Autio standing casually in jeans and work shirts. The Bray has certainly evolved since 1952, a time contributions made Gary & Joan Anderson Kathryn Boeckman Howd Akio Takamori p Andrew & Keith Miller Alanna DeRocchi p Elizabeth A. Rudey p Barbara & Joe Brinig Anita, Janice & Joyce Lammert Spurgeon Hunting Group Dawn Candy Michael Jones McKean John Murdy Archie Bray Foundation Archie Bray They came from vastly different cultural and when studio opportunities for ceramic artists January 1 through Target Jeffry Mitchell p Mary Jane Edwards Renee Brown p Marjorie Levy & Larry Lancaster Abigail St. -

Betty Woodman

BETTY WOODMAN 1930-2018 Born 1930, Norwalk, CT lived and worked in Boulder, CO, New York, NY, and Antella, Italy EDUCATION 1950 Alfred University, The School for American Craftsmen, Alfred, NY SELECTED SOLO / TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS (* indicates a publication) 2019 Shadows and Silhouettes, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2018 The House and The Universe, chi K11 Art Museum, Shanghai, China Betty Woodman: Ceramics with Painting of the Modern Age, presented by the Liverpool Biennial and Cooper Gallery, Cooper Gallery, Barnsley, England Gestural Interactions, Loveland Museum, Loveland, CO AUDACIOUS: A Posthumous Exhibition Honoring Betty Woodman, 15th Street Gallery, Boulder, Colorado 2017 Betty Woodman: Recent Works, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill Roma, Rome, Italy Florentine Interiors, Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, Austria Galeries Royales Saint-Hubert, Brussels, Belgium 2016 *Betty Woodman: In The Garden, curated by Patterson Sims, Greenwood Gardens, Short Hills, NJ Kiki Smith, Betty Woodman, Galleria Lorcan O'Neill Roma, Rome, Italy Dialogue: Betty Woodman / Sol LeWitt, James Barron Art, Kent, CT Breakfast at the Seashore Lunch in Antella, Salon 94 Bowery, New York, NY *Betty Woodman: Theatre of the Domestic, curated by Vincenzo De Bellis, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, England 2015 Betty Woodman, curated by Vincenzo De Bellis, Museo Marino Marini, Florence, Italy Betty Woodman, Mendes Wood, São Paulo, Brazil Illusions of Domesticity, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] www.davidkordanskygallery.com -

Betty Woodman – (1930 - )

BETTY WOODMAN – (1930 - ) Betty Woodman‟s retrospective in 2006 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art covered the over 50 years of this unique artist‟s career. While she is perhaps best-known for her exuberant vases and vessels, with their bright, loose surface decoration, she began her ceramic career as a production potter and believes her current work still pays homage to the traditions of ceramic art. More recently she has been making large-scale installations as well as exploring other media such as bronze and print-making. Woodman and her husband,painter/photographer George Woodman, divide their time between their homes/studios in New York and Italy. ARTIST’S STATEMENT – BETTY WOODMAN “The fragmented object has been with us since cubism. I propose in these recent pieces the fragmented painting as the subject of an object…My work in recent years has evolved from being objects defined by their shapes to being shapes defined by the painting upon them. The shapes are initially composed as ceramic elements, but it is with the application of color that they come to life….I try to make the ceramic and painting parts become separate voices and their interplay like a fugue. In a funny way I think what I am trying to do is to convey the integrity of a painting through echoes of its parts as the ceramic or bronze forms are often echoes or reflections of their parts. The whole thing becomes an oblique mode of representation in which a painting becomes the subject of an object.” 1 1. Quoted from “Convocation Address” given on April 22, 2006, at NSCAD, -

The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art: Selections from the Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection and the Yale University Art Gallery September 4, 2015–January 3, 2016

YA L E U N I V E R S I T Y A R T PRESS For Immediate Release GALLERY RELEASE August 12, 2015 EXHIBITION RE-EXAMINES THE ROLE THAT CLAY HAS PLAYED IN ART MAKING DURING THE SECOND HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art: Selections from the Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection and the Yale University Art Gallery September 4, 2015–January 3, 2016 August 12, 2015, New Haven, Conn.—Over the last 25 years, Linda Leonard Schlenger has amassed one of the most important collec- tions of contemporary ceramics in the country. The Ceramic Presence in Modern Art features more than 80 carefully selected objects from the Schlenger collection by leading 20th-century artists who have engaged clay as an expressive medium—including Robert Arneson, Hans Coper, Ruth Duckworth, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Lucie Rie, and Peter Voulkos—alongside a broad array of artworks created in clay and other media from the Yale University Art Gallery’s perma- nent collection. Although critically lauded within the studio-craft movement, many ceramic pieces by artists who have continuously or periodically worked in clay are only now coming to be recognized as important John Mason, X-Pot, 1958. Glazed stoneware. Linda Leonard Schlenger Collection. © John Mason and integral contributions to the broader history of modern and contemporary art. By juxtaposing exceptional examples of ceramics with great paintings, sculptures, and works on paper and highlighting the formal, historical, and theoreti- cal affinities among the works on view, this exhibition aims to re-examine the contributions of ceramic artists to 20th- and 21st-century art. -

Ceramic Studio

~ P NOVEMBER 1979 $1.2S Often copied but never equaled. ! The Shimpo-West ® R K-2 Over ten years ago Shimpo-West designed and They will tell you their wheels are running as introduced a superior potter's wheel. The first well as the day they brought them home. of its kind. Over the years the few changes The Shimpo-West concept of engineering we've made are only refinements, never changes and craftsmanship is backed by years of prac- for the sake of change.- I tice. We have the practical i The original Shimpo-West ® knowledge it takes to bring Shimpo-West practices the Ring Cone Drive System ~-~iiiiii i. iii~1~ policy of sustained excellence. [-13 you a truly fine, dependable Ask any potters who have wheel. If this is what you're bought Shimpo-West wheels looking for, look to Shimpo- during the last ten years. West. After all, you can't manufacture experience. SHIMPO-WEST INC., 14400 LOMITAS AVE., DEPT. B111, CITY OF INDUSTRY, CA 91746 The Ultimate Extruding Systems System III DoubleAction Air Drive w/Foot PedalControl (100 psi ...by Bailey Compressoroptional) Mountedon: OptionalFloor Stand w/ExternalExtruding Fixtures ExtrusionCapacity: Consider this: 8"L x 8"W x Any Length An extruder that is Power Driven and Foot Pedal Controlled to offer effortless extrud- ing, while leaving both hands free to manipulate the form. An extruder capable of extruding slabs 24"wide, boxes, tubes, and multisided forms up to 8"across, spheres, etc. Interchangeable Extrusion Barrels that clip on and off for easy cleaning or multiple clay body extruding System