Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CVAN Open Letter to the Secretary of State for Education

Press Release: Wednesday 12 May 2021 Leading UK contemporary visual arts institutions and art schools unite against proposed government cuts to arts education ● Directors of BALTIC, Hayward Gallery, MiMA, Serpentine, Tate, The Slade, Central St. Martin’s and Goldsmiths among over 300 signatories of open letter to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson opposing 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects in higher education ● The letter is part of the nationwide #ArtIsEssential campaign to demonstrate the essential value of the visual arts This morning, the UK’s Contemporary Visual Arts Network (CVAN) have brought together leaders from across the visual arts sector including arts institutions, art schools, galleries and universities across the country, to issue an open letter to Gavin Williamson, the Secretary of State for Education asking him to revoke his proposed 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects across higher education. Following the closure of the consultation on this proposed move on Thursday 6th May, the Government has until mid-June to come to a decision on the future of funding for the arts in higher education – and the sector aims to remind them not only of the critical value of the arts to the UK’s economy, but the essential role they play in the long term cultural infrastructure, creative ambition and wellbeing of the nation. Working in partnership with the UK’s Visual Arts Alliance (VAA) and London Art School Alliance (LASA) to galvanise the sector in their united response, the CVAN’s open letter emphasises that art is essential to the growth of the country. -

Collaborative Relationshipsaid & Abet

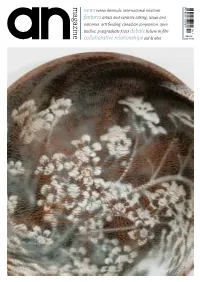

news venice biennale, international relations features artists and curators talking: issues and outcomes, arts funding: canadian comparison, open studios, postgraduate focus debate believe in film JUNE 2011 collaborative relationships aid & abet £5.95/ 8.55 11 MAY–26 JUN 13 JUL–28 AUG 7 MAY– 26 JUN JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA on tour London London DLI Museum & Art Gallery, Durham An exhibition of new works by Selected artists Farah the inaugural Jerwood Painting Bandookwala, Emmanuel Final chance to see the 2010 Fellows; Clare Mitten, Cara Boos, Heike Brachlow exhibition selected by Charles Nahaul and Corinna Till. and Keith Harrison exhibit Darwent, Jenni Lomax and newly commissioned work. Emma Talbot. Curated by mentors; Paul Bonaventura, The 2011 selectors are durham.gov.uk/dli Stephen Farthing RA Emmanuel Cooper, Siobhan Twitter: #JDP2010 and Chantal Joffe. Davis and Jonathan Watkins. jerwoodvisualarts.org jerwoodvisualarts.org CALL FOR ENTRIES 2011 Twitter: #JPF2011 Twitter: #JMO2011 Deadline: Mon 20 June at 5pm The 2011 selectors are Iwona Blazwick, Tim Marlow and Rachel Whiteread. Apply online at jerwoodvisualarts.org Twitter: #JDP2011 Artist Associates: Beyond The Commission Saturday 16 July 2011, 10.30am – 4pm The Arts University College at Bournemouth | £30 / £20 concessions Artist Associates: Beyond the Commission focuses on the practice of supporting artists within the contemporary visual arts beyond the traditional curatorial, exhibition and commissioning role of the public sector, including this mentoring, advice, advocacy, and training. Confirmed Speakers: Simon Faithfull, (Artist and ArtSway Associate) Alistair Gentry (Artist and Writer, Market Project) Donna Lynas (Director, Wysing Arts Centre) Dida Tait (Head of Membership & Market Development, Contemporary Art Society) Chaired by Mark Segal (Director, ArtSway). -

Daswa Medal Finally Launched

newsnewsA publication of the Catholic Archdiocese of Johannesburg 5 7 Synod results Justice&Peace Heritage Day 8 Colour coordination at St Peter Claver Telephone (011) 402 6400 • www.catholicjhb.org.za NOVEMBER 2017 ADSt Peter Claver, Pimville parishioners – Tics Dladla, who contributes ADmusically, Sello Mokoka the extra-ordinary minister of the Eucharist and Thandi Frere from liturgy all in full colour coordination at a recent celebra- Daswa medal finally tion of Sunday Mass. launched PASTORAL LETTER from Archbishop Buti Tlhagale Mary and the Struggles of Women n South Africa during the month of August, the frustrations, struggles, “Living relics”: Vhutshilo Daswa, aspirations, the enduring strength, the collective power and triumphs of Zwothe Daswa, Mulalo Sedumedi Iwomen and forcefully drawn to the attention of the nation. It is also a and Thabelo Daswa. month during which men’s worldview and attitudes towards women are placed under fierce scrutiny. The clarion call is for justice, equality and he official Daswa devotional inclusive participation. medallion was launched on Sunday, 1 October at the Recalling the pain of women T Sacred Heart Cathedral in Pretoria. Mary is an example of a woman who endured pain and suffering. This is in spite of the fact that she had found favour with God, and carried the title About 400 people attended the “full of grace” (gratia plena). In spite of that, she and her family had to flee Mass which was celebrated by from Israel and became refugees in Egypt. Many women today can identify Bishop Joao Rodrigues of Tzaneen. with her pain and suffering. Many flee their countries of origin with no Fathers Amos Masemola, the possessions except the clothes on their back. -

Fracchia Umd 0117E 15193.Pdf (9.069Mb)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: LABORING IN STONE: THE URBANIZATION OF CAPITAL IN THE QUARRY TOWN OF TEXAS, MARYLAND, AND ITS EFFECTS, 1840 TO 1940 Adam D. Fracchia, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation directed by: Professor Stephen A. Brighton Department of Anthropology Capitalism is founded on the unequal relationship between capital and labor, a relationship that along with the expansion and accumulation of capital and labor power has come to influence everyday life and values. The quarry town of Texas, in Baltimore County, Maryland, offers an opportunity to explore this important relationship between labor and capital. Established in the mid-nineteenth century to quarry and burn limestone at a time of expanding industry and an expanding nation. The town was created to house the workers, primarily Irish immigrants and later African Americans hired to toil in this hazardous industry, and a community was formed and eventually destroyed. This study examines the logic and process of capitalism, drawing on David Harvey’s theoretization of the urbanization of capital to understand how life at Texas was influenced by capitalism. The role of and changes to the quarry industry’s operations are studied along with their impact on life in Texas and how industry aligned social relations in town to facilitate capitalism through the manipulation of material culture and space. Through an analysis of the built landscape and artifacts of everyday life, such as ceramic tableware and smoking pipes, in their social context, daily interactions can be studied within a wider framework and scale. Studying Texas in this manner demonstrates the utility and necessity of using a totalizing approach, as suggested by Harvey, to examine capitalism in historical archaeology. -

The Fire Station Project the Fire Station

THE FIRE STATION PROJECT THE FIRE STATION THE FIRE STATION PROJECT THE FIRE STATION PROJECT ACME STUDIOS’ WORK/LIVE RESIDENCY PROGRAMME 1997 – 2013 1 THE FIRE STATION PROJECT Published in 2013 by Acme Studios 44 Copperfield Road London E3 4RR www.acme.org.uk Edited by Jonathan Harvey and Julia Lancaster Designed by AndersonMacgee/Flit London Typeset in DIN and Avenir Printed by Empress Litho The Fire Station Project copyright © Acme Studios and the authors ISBN: 978-0-9566739-5-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and the publishers. Cover illustrations: Robert Ian Barnes Architects 2 Acme Studios is a London-based housing charity dedicated to supporting artists in economic need through the provision of studios, accommodation and professional support. Acme manages 16 buildings providing affordable, long-term and high-quality studios (620) units and work/live space (20 units). Through this resource it helps over 700 artists each year. Acme’s Residency & Awards Programme adds to this core service of studio provision by awarding selected UK-based artists with studio residencies, bursaries, professional mentoring and exhibiting opportunities at the Acme Project Space, working with a range of partners. At any one time over 20 artists benefit from this support. Acme’s International Residencies Programme currently manages 23 annual London residencies on behalf of eight agencies together with an Associate Artist Residencies programme for international artists applying directly to the organisation. -

611 South Third Street 423

611 South Third Street 423 South 5th Street www.stmichaelstillwater.org www.stmarystillwater.org Parish Office: 651-439-4400 | Fax: 651-430-3271 651-439-1270 | Fax: 651-439-7045 www.stcroixcatholic.org School Office: 651-439-5581 After-Hour Clergy Emergency Line 651-430-1551 Entrance Antiphon: Cf. Esther 4:17: Within your will, O Lord, all Gospel: Matthew 21:33-43: Jesus said to the chief priests and the things are established, and there is none that can resist your will. For elders of the people: "Hear another parable. There was a landowner you have made all things, the heaven and the earth, and all that is who planted a vineyard, put a hedge around it, dug a wine press in it, held within the circle of heaven; you are the Lord of all. and built a tower. Then he leased it to tenants and went on a journey. When vintage time drew near, he sent his servants to the tenants to Processional: Hymn 711: Praise, my soul, the King of heaven; To his obtain his produce. But the tenants seized the servants and one they feet your tribute bring. Ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven, beat, another they killed, and a third they stoned. Again he sent other Evermore his praises sing. Alleluia! Alleluia! Praise the everlasting servants, more numerous than the first ones, but they treated them King. / Praise him for his grace and favor To his people in distress, in the same way. Finally, he sent his son to them, thinking, 'They will Praise him, still the same as ever, Slow to chide and swift to bless. -

Nicky Hirst *1963 Nottingham/Leeds/Kenya Currently Lives and Works in London

DOMOBAAL nicky hirst *1963 nottingham/leeds/kenya currently lives and works in london 1993 - 1994 ma art and architecture, kiad, canterbury 1982 - 1985 ba fine art, maidstone college of art, kent 1981 - 1982 foundation course, jacob kramer college, leeds solo and two-person exhibitions (selected) 2019 : exeter phoenix, exeter, uk 2018 : white roses, entractes #1, the eye sees, arles, france : casement arts, folkestone, uk : elemental works, domobaal, london : briar rose, m2 gallery, london 2017 : real size, domobaal, london : invisible mending, amp peckham, london 2016 : museo d’arte contemporanea di cogliandrino, basilicata, italy, invited by stephen nelson : collaboration with remi rough, beer shop brock street mural, nunhead, london 2008 : morphology, with doug burton, curated by michael petry, royal academy schools gallery, london 2004 : indiana ain't pink, floor 30 clifford chance building, london 2001 : anthony wilkinson gallery, london 2000 : fellowship exhibition (with mary evans) byam shaw school of art, london 1997 : perforated observations, iniva, london 1996 : cordon sanitaire, imperial war museum, invited by roger tolson, iwm, london : cell 3, barbican foyer gallery, barbican centre, curated by julia bunnage, london : anthony wilkinson gallery, london 1995 : limited edition multiple, soho house, london 1994 : wall drawing, homerton hospital, london : wall drawing, darlington arts centre, uk 1993 : tongue and groove, 181 gallery, london : caught looking, catalogue with an essay by gregor muir, dash gallery, london 1991 : adam -

1795 1795 1795 1795 1796 1796 Large Date, 1797

C ATAL O GUE . AMERICAN D OLLARS . 1 79 5 F l u ll . ow in u n u s a g hair, y fine 1 79 5 do not qu it e so good . 1 7 95 v . Fillet head , ery fine 1 7 9 5 do fine . 1 7 96 S m all v . date , ery fine 1 7 9 6 Large date , do . 1 79 7 Very good . 1 9 8 7 v . Large eagle , ery fine 1 7 9 8 ff v d . Di erent die , ery goo 1 9 9 7 Fine impression . 1 8 0 0 Remarka bly fin e . 1 00 8 Nearly as g oo d . 1 8 01 Very goo d . 1 802 b Remarka ly fine impression . 1 8 03 Not often foun d as fine . 1 8 03 Very fine . 1 8 3 9 v b b Flying eagle , ery little ru ed , otherwise 1 840 b t Li er y seated , fine pro of, extremely rare . 1 84 1 Nearly uncirculate d . 1 842 Re markab ly fine . 1 844 Very fine impression . 1 84 5 Very good . 1 84 6 Bu t very little tarnished . 1 847 Uncirculated . 1 848 In fine condition . 1 849 Very fine . 1 85 0 v fi n e . Uncirculated , ery 1 8 53 Uncirculated . 1 8 53 Very good . 4 1 8 5 v . Fin e proof, ery rare 1 8 54 Fine condition . 1 855 Very good . 1 8 56 Goo d an d fine condition . AMERICAN D O LLARS . -

OSV 2018 Christmas Gift Guide

OSV 2018 Christmas Gift Guide It’s hard to believe that Christmas is right around the corner. And while we must never overlook the beautiful season of Advent, it’s not too early to start thinking about Christmas gift ideas for loved ones — especially those that will help the recipient better live their Catholic faith. For this year’s guide, we’ve chosen a wide variety of Catholic gifts intended to appeal to the whole family, and we hope that this gift guide will be an inspiration for you as the season draws near. Lori Hadacek Chaplin writes from Idaho. GIFTS FOR LADIES Kashmiri Shawls & Leather Bags Help impoverished artisans in India get a fair price for their hand-dyed Kashmiri shawls and leather bags. The shawls — made of silk and a cotton-wool blend — come in five different vibrant hues and patterns. The leather bags are also handmade in India and come in a variety of colors and sizes. Price: Shawl $58 (79” L x 27” W); Bags $148-$168 Website: EthicalTrade.CRS.org ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Shield of Michael the Archangel Earrings Women who like to wear jewelry that makes a statement will appreciate these handmade Shield of Michael the Archangel Earrings from Catholic jewelry artist Gail Giron. The earrings feature St. Michael’s wings embellished with a bright turquoise bead and deep red Swarovski crystals. Price: $38 Website: GailsDesigns.net ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Necklace of Holy Love Another statement piece is this necklace from Seraphym Designs. The necklace (20”) has warm-toned champagne-colored crystal beads with aqua crystal accents. The beads encircle a solid bronze, hand-cast, ornate cross (2” tall) with two kissing doves perched on the Sacred Heart (1” tall). -

Modern and Contemporary.Pdf

The article was first published in October 2008 in: Festschrift Tuukka Talvio, Scripta varia numismatico Tuukka Talvio sexagenario dedicata, Suomen Numismaattinen Yhdistys 6 (Publications of the Finnish numismatic Society, no. 6) Aimo Linkosalmi (ed.), Helsinki 2008, pp. 201-223. This is mainly an unaltered edition, with only a few minor corrections as of January 5th 2009. All illustrated medals belong to the collection of medals at the University Museum in Bergen, photographed by the museum photographer Svein Skare. Modern and Contemporary Religious Medals and Medallic Art Henrik von Achen ‘Was es zu sehen gilt, ist das Aufgenommensein göttlicher Offenbarung in den Schoss des durch die Gnade der Offenbarung selbst erwirkten menschlichen Glaubens; von diesem Schoss will sie aufgenommen, getragen, zur Welt gebracht werden’. Hans Urs von Balthasar, in Schau der Gestalt , 1961. 1 The present text endeavours to offer a brief survey of the various categories of religious medals and religious medallic art since the 1960s. In this context, the term ‘religious’ is synonymous with ‘Christian’ (with a single exception), and within Christianity mainly, if not exclusively, synonymous with ‘Catholic’. The traditional concept of religious medals is – and must be – widened to include medallic art which is religious in the sense that a relation to faith and religion is articulated by employment of an individual iconography and a title, or by elements from the established Christian iconography. While traditional religious medals, the numismata sacra 2, have a very long history, indeed – almost as long as Christianity itself – the latter group of medallic art or objects is by and large a modern phenomenon. -

Archaeological

flALBERTA 1 (ArchaeologicaNo. 37 ISSN 0701-1176 Fall 2002 l Contents 2 Provincial Society Officers, Features 2002-2003 11 A Miraculous Medal from Rocky 3 Editor's Note Mountain House National Historic 3 Past Editor's Report Site, Alberta 4 2002 Annual General Meeting 15 January Cave: An Ancient Window 6 Centre Reports on the Past 10 Diane Lyons Appointment 17 Alberta Graduate Degrees in 20 Recent Abstracts Archaeology, Part 1 36 Wahkpa Chu'gn Buffalo Jump Grand 21 Archaeological Survey of Alberta Opening Issued Permits, December 2001 - 36 In Memory October 2002 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF ALBERTA Charter #8205, registered under the Societies Act of Alberta on February 7, 1975 PROVINCIAL SOCIETY OFFICERS 2002-2003 President Marshall Dzurko RED DEER CENTRE. 147 Woodfern Place SW President: Shawn Haley Calgary AB T2W4R7 R.R. 1 Phone:403-251-0694 Bowden.AB TOM 0K0 Email: [email protected] Phone: 403-224-2992 Email: [email protected] Past-President Neil Mirau 2315 20* Street SOUTH EASTERN ALBERTA CoaldaleAB TIM 1G5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY: Phone: 403-345-3645 President: Lorine Marshall 97 First Street NE Executive Secretary/ Jim McMurchy Medicine Hat AB T1A 5J9 Treasurer 97 Eton Road West Phone: 403-527-2774 Lethbridge AB T1K4T9 Email: [email protected] Phone:403-381-2655 Email: [email protected] STRATHCONA CENTRE: President: Kristine Wright-Fedynyak Alberta Archaeological Dr. John Dormaar Provincial Museum of Alberta Review Editor Research Centre 12845 102 Ave Agr. & Agri-Food Canada Edmonton AB T5N 0M6 PO Box 3000 Provincial Rep: George Chalut Lethbridge AB T1J4B1 Email: [email protected] Alberta Archaeological Carol Mcreary Review Distribution Box 611 Black Diamond AB T0L0H0 Alberta Archaeological Review Phone:403-933-5155 Editor: John Dormaar ([email protected]) Email: [email protected] Layout & Design: Larry Steinbrenner ([email protected]) Distribution: Carol Mccreary ([email protected]) REGIONAL CENTRES AND MEMBER SOCIETIES Members of the Archaeological Society of Alberta receive a copy of the Alberta Archaeological Review. -

V&A R Esearch R Eport 2012

2012 REPORT V&A RESEARCH MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Research is a core activity of the V&A, helping to develop the public understanding of the art and artefacts of many of the great cultures of the world. This annual Research Report lists the outputs of staff from the calendar year 2012. Though the tabulation may seem detailed, this is certainly a case where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. The V&A plays a synthetic role in binding together the fields of art, design and performance; conservation and collections management; and museum-based learning. We let the world know about our work through many different routes, which reach as large and varied an audience as possible. Here you will find some listings that you might expect - scholarly journal articles and books - but also television and radio programmes, public lectures, digital platforms. Many of these research outputs are delivered through collaborative partnerships with universities and other institutions. The V&A is international both in its collections and its outlook, and in this Report you will notice entries in French, Spanish, German, and Russian as well as English – and activities in places as diverse as Ukraine, Libya, and Colombia. Most importantly, research ensures that the Museum will continue to innovate in the years to come, and in this way inspire the creativity of others. Martin Roth ASIAN DEPARTMENT ASIAN ROTH, MARTIN JACKSON, ANNA [Foreword]. In: Olga Dmitrieva and Tessa Murdoch, The ‘exotic European’ in Japanese art. In: Francesco eds. The ‘Golden Age’ of the English Court: from Morena, ed.