The Fire Station Project the Fire Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Artists' Professional Development Programmes in the Uk: Knowledge and Skills

1 REBECCA GORDON-NESBITT FOR CHISENHALE GALLERY SUPPORTED BY PAUL HAMLYN FOUNDATION MARCH 2015 59 PAGES MAPPING ARTISTS’ PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES IN THE UK: KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS 2 COLOPHON Mapping Artists’ Professional Development This research was conducted for Chisenhale Programmes in the UK: Knowledge and Skills Gallery by Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt with funding from Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Author: Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt Editors: Polly Staple and Laura Wilson → Chisenhale Gallery supports the production Associate Editor: Andrea Phillips and presentation of new forms of artistic delivery Producer: Isabelle Hancock and engages diverse audiences, both local and Research Assistants: Elizabeth Hudson and international. Pip Wallis This expands on our award winning, 32 year Proofreader: 100% Proof history as one of London’s most innovative forums Design: An Endless Supply for contemporary art and our reputation for Commissioned and published by Chisenhale producing important solo commissions with artists Gallery, London, March 2015, with support from at a formative stage in their career. Paul Hamlyn Foundation. We enable emerging or underrepresented artists to make significant steps and pursue Thank you to all the artists and organisational new directions in their practice. At the heart of representatives who contributed to this research; our programme is a remit to commission new to Regis Cochefert and Sarah Jane Dooley from work, supporting artists from project inception Paul Hamlyn Foundation for their advice and to realisation and representing an inspiring and support; and to Chisenhale Gallery’s funders, challenging range of voices, nationalities and art Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Arts Council England. forms, based on extensive research and strong curatorial vision. -

CVAN Open Letter to the Secretary of State for Education

Press Release: Wednesday 12 May 2021 Leading UK contemporary visual arts institutions and art schools unite against proposed government cuts to arts education ● Directors of BALTIC, Hayward Gallery, MiMA, Serpentine, Tate, The Slade, Central St. Martin’s and Goldsmiths among over 300 signatories of open letter to Education Secretary Gavin Williamson opposing 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects in higher education ● The letter is part of the nationwide #ArtIsEssential campaign to demonstrate the essential value of the visual arts This morning, the UK’s Contemporary Visual Arts Network (CVAN) have brought together leaders from across the visual arts sector including arts institutions, art schools, galleries and universities across the country, to issue an open letter to Gavin Williamson, the Secretary of State for Education asking him to revoke his proposed 50% cuts in subsidy support to arts subjects across higher education. Following the closure of the consultation on this proposed move on Thursday 6th May, the Government has until mid-June to come to a decision on the future of funding for the arts in higher education – and the sector aims to remind them not only of the critical value of the arts to the UK’s economy, but the essential role they play in the long term cultural infrastructure, creative ambition and wellbeing of the nation. Working in partnership with the UK’s Visual Arts Alliance (VAA) and London Art School Alliance (LASA) to galvanise the sector in their united response, the CVAN’s open letter emphasises that art is essential to the growth of the country. -

Little Things Make Big Things Happen - Celebrating Success in a Challenging Environment

little things make big things happen - celebrating success in a challenging environment Richmond Fellowship is a registered social landlord (Housing Corporation Registration No. H2025), a registered charity (Registration No. 200453) and a company limited by guarantee (No. 662712). Richmond Fellowship’s Board adopted the National Housing Federation Code of Governance in 1996. Richmond Fellowship is a member of the Independent Housing Ombudsman Scheme. 02 little things make big things happen - celebrating success in a challenging environment BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Brindle Derek Caren, Chief Executive Peter Corley, Chair ‘Our mission is: Barbara Deacon-Hedges Stephanie De La Haye Diane French, Director of Performance and Quality making Nigel Goldie Ian Hughes Raj Lakhani, Director of Finance Rebecca Pritchard recovery Stuart Riggall, Director of People and Organisation Development Kevin Tunnard, Director of Operations AUDIT AND ASSURANCE COMMITTEE reality Peter Corley Barbara Deacon-Hedges, Chair David Kennedy Rebecca Pritchard creating our future... step by step! 4 REMUNERATION COMMITTEE success in a challenging environment 6 Peter Corley Barbara Deacon-Hedges challenges and opportunities 7 Nigel Goldie, Chair learning from the olympics 8 small steps, big achievements 10 PATRON a snapshot of what service users achieved, in their own words! 16 HRH Princess Alexandra and finally, great staff make great differences 18 VICE PATRON annual accounts & staff statistics 2012 20 The Most Reverend and Right Honourable Dr. Rowan Williams, statutory sector purchasers 22 Archbishop of Canterbury HEAD OFFICE 80 Holloway Road For more information about RF’s work and its Services, please contact: London N7 8JG Marise Willis: T: 020 7697 3359 E: [email protected] T: 020 7697 3300 or visit our website www.richmondfellowship.org.uk F: 020 7697 3301 www.richmondfellowship.org.uk 03 little things make big things happen - celebrating success in a challenging environment Creating our future.. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Nikolopoulou, Marialena and Martin, Karen and Dalton, Ben (2015) Shaping pedestrian movement through playful interventions in security planning: what do field surveys suggest? Journal of Urban Design . pp. 1-21. ISSN 1357-4809. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1106913 Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/53859/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Journal of Urban Design ISSN: 1357-4809 (Print) 1469-9664 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjud20 Shaping pedestrian movement through playful interventions in security planning: what do field surveys suggest? Marialena Nikolopoulou, Karen Martin & Ben Dalton To cite this article: Marialena Nikolopoulou, Karen Martin & Ben Dalton (2015): Shaping pedestrian movement through playful interventions in security planning: what do field surveys suggest?, Journal of Urban Design, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2015.1106913 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2015.1106913 © 2016 The Author(s). -

Collaborative Relationshipsaid & Abet

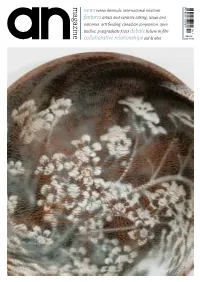

news venice biennale, international relations features artists and curators talking: issues and outcomes, arts funding: canadian comparison, open studios, postgraduate focus debate believe in film JUNE 2011 collaborative relationships aid & abet £5.95/ 8.55 11 MAY–26 JUN 13 JUL–28 AUG 7 MAY– 26 JUN JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA at Jerwood Space, JVA on tour London London DLI Museum & Art Gallery, Durham An exhibition of new works by Selected artists Farah the inaugural Jerwood Painting Bandookwala, Emmanuel Final chance to see the 2010 Fellows; Clare Mitten, Cara Boos, Heike Brachlow exhibition selected by Charles Nahaul and Corinna Till. and Keith Harrison exhibit Darwent, Jenni Lomax and newly commissioned work. Emma Talbot. Curated by mentors; Paul Bonaventura, The 2011 selectors are durham.gov.uk/dli Stephen Farthing RA Emmanuel Cooper, Siobhan Twitter: #JDP2010 and Chantal Joffe. Davis and Jonathan Watkins. jerwoodvisualarts.org jerwoodvisualarts.org CALL FOR ENTRIES 2011 Twitter: #JPF2011 Twitter: #JMO2011 Deadline: Mon 20 June at 5pm The 2011 selectors are Iwona Blazwick, Tim Marlow and Rachel Whiteread. Apply online at jerwoodvisualarts.org Twitter: #JDP2011 Artist Associates: Beyond The Commission Saturday 16 July 2011, 10.30am – 4pm The Arts University College at Bournemouth | £30 / £20 concessions Artist Associates: Beyond the Commission focuses on the practice of supporting artists within the contemporary visual arts beyond the traditional curatorial, exhibition and commissioning role of the public sector, including this mentoring, advice, advocacy, and training. Confirmed Speakers: Simon Faithfull, (Artist and ArtSway Associate) Alistair Gentry (Artist and Writer, Market Project) Donna Lynas (Director, Wysing Arts Centre) Dida Tait (Head of Membership & Market Development, Contemporary Art Society) Chaired by Mark Segal (Director, ArtSway). -

Nicola L. Hein – Klangkunst Als Philosophie

Klangkunst als Philosophie Nicola L. Hein 0 Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Philosophisches Konzept 1 1.1 Einleitung 1 1.2 Der Begriff der Klangkunst 5 1.3 Familienähnlichkeit und Klangkunst 10 1.4 Was ist Philosophie? 17 1.5 Alva Noë, Georg Bertram, Richard Rorty: Philosophie und Kunst 21 1.6 Was ist Klangkunst? 27 1.7 Cox: Klangkunst als Gestaltung der Frage: „Was ist Klang“? 28 1.8 Klangkunst als Diskurs 33 1.9 Klangkunst und Skepsis 38 1.10 Bestimmungen der Klangkunst in der künstlerischen Praxis 43 1.11 Klangkunst als Philosophie 58 2. Darstellung: „Sokratischer Versuch über politische Kontingenz“ 65 2.1 Das Konzept 65 2.2 Die Änderungen 71 2.3 Die Durchführung 81 2.4 Wurde Anspruch der Klangkunst als Philosophie eingelöst? 95 3. Perspektiven 99 4. Quellenverzeichnis 100 4.1 Literaturverzeichnis 100 4.2 Abbildungsverzeichnis 105 1 1. Philosophisches Konzept 1.1 Einleitung Die Geschichte der Kunstform, die unter dem Namen der Klangkunst oder der sound art bekannt ist, ist von unterschiedlichen definitorischen Versuchen gekennzeichnet. Die interpretatorischen und definitorischen Differenzen unterschiedlicher WissenschaftlerInnen, KünstlerInnen und JournalistInnen weisen dabei eine enorme Spannweite auf. Was ist Klangkunst? Welche Objekte, Handlungsformen und Prozessen fallen unter ihren Begriff und welche Merkmale weißt jene Kunstform auf? Wie lässt sich Klangkunst abgrenzen von anderen Formen der Kunst, wie etwa der Neuen Musik, der Improvisierten Musik, der Performance Art, der Skulptur und der Plastik? Gegenüber dieser Entwicklung soll gerade die Heterogenität des Entwurfs der Klangkunst dazu genutzt werden, den Versuch einer Definition zu wagen, die diese aus einem anderen Winkel heraus betrachtet und versteht, indem sie die bereits in der künstlerischen und theoretischen Praxis auffindbaren Bestandteile zusammenfügt und diese in eine spezifische Direktion weiter denkt. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lockett, P.W. (1988). Improvising pianists : aspects of keyboard technique and musical structure in free jazz - 1955-1980. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8259/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] IMPROVISING PIANISTS: ASPECTS OF KEYBOARD TECHNIQUE AND MUSICAL STRUCTURE IN FREE JAll - 1955-1980. Submitted by Mark Peter Wyatt Lockett as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University Department of Music May 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No I List of Figures 3 IIListofRecordings............,........ S III Acknowledgements .. ..... .. .. 9 IV Abstract .. .......... 10 V Text. Chapter 1 .........e.e......... 12 Chapter 2 tee.. see..... S S S 55 Chapter 3 107 Chapter 4 ..................... 161 Chapter 5 ••SS•SSSS....SS•...SS 212 Chapter 6 SS• SSSs•• S•• SS SS S S 249 Chapter 7 eS.S....SS....S...e. -

David Toop Ricocheting As a 1960S Teenager Between Blues Guitarist

David Toop Ricocheting as a 1960s teenager between blues guitarist, art school dropout, Super 8 film loops and psychedelic light shows, David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music and materials since 1970. This practice encompasses improvised music performance (using hybrid assemblages of electric guitars, aerophones, bone conduction, lo-fi archival recordings, paper, sound masking, water, autonomous and vibrant objects), writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations and opera (Star-shaped Biscuit, performed in 2012). It includes seven acclaimed books, including Rap Attack (1984), Ocean of Sound (1995), Sinister Resonance (2010) and Into the Maelstrom (2016), the latter a Guardian music book of the year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Music Book Prize. Briefly a member of David Cunningham’s pop project The Flying Lizards (his guitar can be heard sampled on “Water” by The Roots), he has released thirteen solo albums, from New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments on Brian Eno’s Obscure label (1975) and Sound Body on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label (2006) to Entities Inertias Faint Beings on Lawrence English’s ROOM40 (2016). His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism and ritual - released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows (2016) - were called by The Wire a “tsunami of weirdness” while Entities Inertias Faint Beings was described in Pitchfork as “an album about using sound to find one’s own bearings . again and again, understated wisps of melody, harmony, and rhythm surface briefly and disappear just as quickly, sending out ripples that supercharge every corner of this lovely, engrossing album.” In the early 1970s he performed with sound poet Bob Cobbing, butoh dancer Mitsutaka Ishii and drummer Paul Burwell, along with key figures in improvisation, including Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Georgie Born, Hugh Davies, John Stevens, Lol Coxhill, Frank Perry and John Zorn. -

Special Exhibition Gallery

SPECIAL EXHIBITION GALLERY Stories in the Dark Artist statements Adam Chodzko Ask the Dust 2016 Carousel slide projector and 81 x 35mm photographic slides, each containing dust taken from inside the barrel of a cannon (captured from the Chinese in 1860 during the Second Opium War) held in the Beaney Museum’s storage. Dimensions variable Duration 5 mins A slide projector back-projects ‘images’ of dust ‘explosions’ onto a blind in the Explorers and Collectors gallery, sharing this ‘screen’ with moving patches of sunlight, channeled by a large arched window. The dust silhouettes are formed by tiny particles of debris, decay collected from the barrel of a cannon (captured from the Chinese during the Second Opium War, 1860) stored in the Beaney’s archives. Their apparently random arrangements, suspended in 35mm film slide mounts, now magnified, offer the possibility of being decoded and read, like tea leaves, as premonitions. Or perhaps as the animated frames from a recording of Chinese shadow puppet performance. Exhibiting since 1991, working across media, from video installation to subtle interventions, and with a practice that is situated both within the gallery and the wider public realm, Chodzko’s work explores our collective imagination by wondering how, through the visual, we might best engage with the existence of others. His art proposes new relationships between our value and belief systems, exploring their affect on our communal and private spaces and the documents and fictions that control, describe and guide them. Chodzko’s practice operates between documentary and fantasy, (often using a form of “science fiction”, in order that art might propose alternative realities), conceptualism and surrealism and public and private space, often engaging reflexively and directly with the role of the viewer. -

Unauthored Music and Ready-Made Landscapes: Aeolian Sound Sculpture

V ADIM K EYLIN Unauthored Music and Ready-Made Landscapes: Aeolian Sound Sculpture Introduction he Aeolian harp and its various relatives – Roman wind chimes, Chinese musical kites and others – are arguably the earliest examples of sound sculpture. The Tinstruments that are “played on” by the natural forces without a composer or a performer present have a long and well-documented history of being employed in areas as diverse as religious ceremonies, warfare or landscape design. However, their role in contemporary sound art remains somewhat underexplored. The articles on Aeolian art usually focus on describing the various ways musical instruments can be powered by the natural forces and listing the artists employing them.1 However, they limit themselves to technical descriptions, discussing neither the aesthetical and political implications of such practices, the artistic challenges they present, nor the audience’s experience. On the other hand, the works on sound art in natural landscapes2 and public spaces3 do not differentiate between various kinds of sound art, overlooking the specifics of Aeolian sculptures. My aim in this article is to provide, through a discussion of selected works by Max Eastley, Annea Lockwood, Gordon Monahan and Jodi Rose, an in-depth analysis of the mechanics of Aeolian sound sculpture. To this end I will review them from three different angles: as musical pieces, as works of environmental art and as tools of urban architectural design, focusing on the ways such works engage their audiences and the landscapes, either natural or urban, they exist in. 1 Cf. HUGH DAVIES, Sound Sculpture, in Grove Music Online. -

Bbc Corporate Responsibility Performance Review 2012

BBC CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY PERFORMANCE REVIEW 2012 For more information see www.bbc.co.uk/outreach 2 Contents Welcome to our latest Corporate Responsibility Performance Review, the last during my time as Director-General. Introduction 3 The BBC’s focus as an international public service broadcaster continues to be on distinctive output, improved value for money, Outreach and the BBC’s Public Purposes 5 doing more to serve all our audiences and being even more open about what we do. Our strategic six-year plan, Delivering Quality Sustainability 13 First, and the long term savings we need to find to live within our means have inevitably meant some tough choices in 2011/12; Our Business 18 however, some things are not negotiable. Supporting Charities 25 BBC licence fee payers expect high quality content across our services; they also expect the BBC to meet the highest standards in Looking Ahead 30 how we behave as an organisation. I believe we are delivering on both of those expectations. In this remarkable year for the UK it has been a source of pride that the work we do beyond broadcasting to benefit our audiences has been so imaginative, collaborative and far-reaching. Cover image: Stargazing Live Oxfordshire, A Stargazing LIVE event at the Rollright Stones, Oxfordshire, organised by Chipping Norton Amateur Astronomy Group attracted around 150 enthusiasts. Mark Thompson Photo: Mel Gigg, CNAAG For more information about other areas of our business, please 3 Introduction see the BBC Annual Report and Accounts the London 2012 Apprenticeships scheme is now building an Olympics legacy in training and careers. -

An Introduction to Corporate Responsibility at the BBC

AN INTRODUCTION TO CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY AT THE BBC For more information, see www.bbc.co.uk/outreach. “ WE SUPPORT OUTREACH INITIATIVES ACROSS THE BBC’S SIX PUBLIC PURPOSES. THESE ACTIVITIES BRING US faCE-TO-faCE WITH OUR AUDIENCES, AND OFTEN INCLUDING THOSE HARDER TO REACH THROUGH BROADCASTING.” ALEC MCGIVAN, HEAD OF BBC OUTREACH COVER Young viewers operating a camera at the National Media Museum in Bradford during February’s half-term, when the EastEnders interactive experience and display came to town. 01 INTRODUCTION 12 CHARITIES 02 THE BBC’S PURPOSES 16 MAJOR INITIATIVES 04 BEYOND THE BROADCAST AND PLANS 08 ENVIRONMENT 17 TEAM INTRODUCTION CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY, OUTREACH AND PARTNERSHIP WORK ARE CENTRAL TO THE BBC, AND A STRONG SENSE OF PUBLIC SERVICE IS AT THE HEART OF ALL THAT WE DO. The BBC Outreach team is responsible for developing Corporate Responsibility Policy and Strategy for the BBC as well as promoting sustainable business and ethical practises across the organisation. We are also the part of the BBC that tracks and measures the BBC’s environmental impact. During the year, we once again took part in Business in the Community’s Corporate Responsibility Index and maintained our Platinum ranking, reflecting the high standards we aim to achieve in managing our business responsibly. A major part of our function is to support outreach initiatives across the BBC, and communicate the impact of this ‘beyond broadcast’ work throughout the year. We also run two of the BBC’s corporate charities – the BBC Wildlife Fund and the BBC Performing Arts Fund – and work throughout the year to support these causes.