Use of the Kaibab Lesson in Teaching Biology Christian C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Forest Action Plan 2015 Status Report and Addendum

Arizona Forest Action Plan 2015 Status Report and Addendum A report on the strategic plan to address forest-related conditions, trends, threats, and opportunities as identified in the 2010 Arizona Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy. November 20, 2015 Arizona State Forestry Acknowledgements: Arizona State Forestry would like to thank the USDA Forest Service for their ongoing support of cooperative forestry and fire programs in the State of Arizona, and for specific funding to support creation of this report. We would also like to thank the many individuals and organizations who contributed to drafting the original 2010 Forest Resource Assessment and Resource Strategy (Arizona Forest Action Plan) and to the numerous organizations and individuals who provided input for this 2015 status report and addendum. Special thanks go to Arizona State Forestry staff who graciously contributed many hours to collect information and data from partner organizations – and to writing, editing, and proofreading this document. Jeff Whitney Arizona State Forester Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial On the second anniversary of the Yarnell Hill Fire, the State of Arizona purchased 320 acres of land near the site where the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots sacrificed their lives while battling one of the most devastating fires in Arizona’s history. This site is now the Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park. “This site will serve as a lasting memorial to the brave hotshots who gave their lives to protect their community,” said Governor Ducey. “While we can never truly repay our debt to these heroes, we can – and should – honor them every day. Arizona is proud to offer the public a space where we can pay tribute to them, their families and all of our firefighters and first responders for generations to come.” Arizona Forest Action Plan – 2015 Status Report and Addendum Background Contents The 2010 Forest Action Plan The development of Arizona’s Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy (now known as Arizona’s “Forest Action Plan”) was prompted by federal legislative requirements. -

KAIBAB DEER HERD MUST BE REDUCED IMMEDIATELY -- October 13,1924

U.S.DEPARTMENT OFAGRICULTURE Office of the Secretary , Pra serviq ” _, RELEASED FOR PUBLICATION, MONDAYMORNING, OCTOBER13, 19+: -9 KAIBAB DEER HERD MUST BE REDUCEDIXMEDIATELY Immediate reduction of the deer herd on the Kaibab National Forest in northern Arizona is strongly urged by the special committee appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture to study and report on the conditions existing on the Grand Canyon Game Preserve, announces the Forest Service, United States Depart- ment of Agricu&are. ! The special committee is composed of John B. Burnham, chairman, repre- senting the American Game Protective Association; Heyward Cutting, of tho Boone and Crockett Club; T. Gilbert Pearson,, of the Audubon Society and the National Parks Association; and T. W. Tomlinson, of the American National Livestock Association. This ccmmittee has made its report to the Secretary of Agriculture following a personal inspection of the Kaibab Plateau on which the Grand Canyon &me Preserve was estabZ.shed in 1906 by President Roosevelt. This area also forms part of the Kaibab Nakional Forest and is under the supervision Of the Forest Servi&. _ . , Upwards of 30,000 head of mule deer are now on the Kaibab Plateau, according to the report of the committee. This is fully twice as many deer as the vegetation can support and the entire herd is in imdnent danger of extinction through starvation unless reduced to a safety number. Moreover, the condition of That forage is still to be found on the ' arsa is far below nornal and several years will be required to grow new forage crops before the region can support more than 15,009 head of deer'in addition to the scattering amal 1 herds of domestic livest.ock owned by settlers living in and around the Kaibab Forest. -

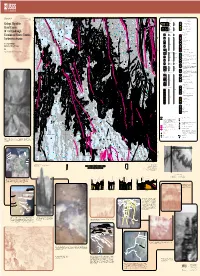

Grand Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Arizona's Wildlife Linkages Assessment

ARIZONAARIZONA’’SS WILDLIFEWILDLIFE LINKAGESLINKAGES ASSESSMENTASSESSMENT Workgroup Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Arizona’s Wildlife Linkages Assessment Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Siobhan E. Nordhaugen, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Evelyn Erlandsen, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Habitat Branch Paul Beier, Northern Arizona University, School of Forestry Bruce D. Eilerts, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Ray Schweinsburg, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Terry Brennan, USDA Forest Service, Tonto National Forest Ted Cordery, Bureau of Land Management Norris Dodd, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Melissa Maiefski, Arizona Department of Transportation, Environmental Planning Group Janice Przybyl, The Sky Island Alliance Steve Thomas, Federal Highway Administration Kim Vacariu, The Wildlands Project Stuart Wells, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT First Printing Date: December, 2006 Copyright © 2006 The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written consent from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written consent of the copyright holder. Additional copies may be obtained by submitting a request to: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup E-mail: [email protected] 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Mission Statement “To identify and promote wildlife habitat connectivity using a collaborative, science based effort to provide safe passage for people and wildlife” 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Primary Contacts: Bruce D. -

Kaibab National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Kaibab National Forest Forest Service Southwestern Potential Wilderness Area Region September 2013 Evaluation Report The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Kanab Creek Wilderness Kaibab National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Inventory of Potential Wilderness Areas .................................................................................................. 2 Evaluation of Potential Wilderness Areas ............................................................................................... -

MTB Participant Manual

MTB Participant Manual Flagstaff to Grand Canyon Stagecoach Line 100-Mile Mountain Bike Race ____________________________________________ Flagstaff, Arizona September 19, 2020 6AM ____________________________________________ Presented by Babbitt Ranches Flagstaff to Grand Canyon 100 Table of Contents Race Management 3 Sponsors 4 Brief Course Description 5 Qualifying 5 Start Times 5 Time Limits & Cut-Off Requirements 5 Race Day Parking 6 Post-Race Transportation 6 Flagstaff, AZ 6 Tusayan, AZ 7 Travel 7 Accommodations 7 Race Weekend Weather 8 Our Partners 9 Awards 12 Race Weekend Agenda 13 Course Marking 14 Aid Stations 14 Race Mechanics 14 Drop Bags 15 Recommended Gear 16 Last Minute Supplies 16 Social Media 16 Aid Station Matrix: Distances, Relay Exchanges, and Services 17 Biker Rules 17 Crew Rules 19 Aid Station Driving Directions 21 Recommended Purchases 24 Detailed Course Description 25 ©2020 The Flagstaff to Grand Canyon Stagecoach Line races are conducted under special use permit of the Coconino and Kaibab National Forests. 2 Flagstaff to Grand Canyon 100 Race Management Race Director Ian Torrence Co-Race Director Emily Torrence Mountain Bike Co-Race Director Dana Ernst Medical Directors Eric True & Scott Bajer Coconino County Sheriff’s SAR Coordinator Bart Thompson Coconino Amateur Radio Club Coordinator Joe Hobart Timing & Tracking Run Flagstaff and UltraLive.net 3 Brief Event Description This mountain bike event begins a few miles north of Flagstaff, Arizona, near the intersection of Snowbowl Road and Route 180, and finishes in Tusayan, Arizona, the entrance of Grand Canyon National Park. A majority of the Stagecoach course follows the Arizona Trail and the historic Flagstaff to Grand Canyon Stagecoach Line route used by adventure seeking tourists between 1897 and 1901. -

A Regional Climatology of Monsoonal Precipitation in the Southwestern United States Using TRMM

310 JOURNAL OF HYDROMETEOROLOGY VOLUME 13 A Regional Climatology of Monsoonal Precipitation in the Southwestern United States Using TRMM CHRISTINA L. WALL,EDWARD J. ZIPSER, AND CHUNTAO LIU University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah (Manuscript received 17 March 2011, in final form 22 June 2011) ABSTRACT Using 13 yr of data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite, a regional climatology of monsoonal precipitation is created for portions of the southwest United States. The climatology created using precipitation features defined from the TRMM precipitation radar (PR) shows that the population of features includes a large number of small, weak features that do not produce much rain and are very shallow. A lesser percentage of large, stronger features contributes most of the region’s rainfall. Dividing the features into categories based on the median values of volumetric rainfall and maximum height of the 30-dBZ echo is a useful way to visualize the population of features, and the categories selected reflect the life cycle of monsoonal convection. An examination of the top rain-producing features at different elevations reveals that extreme features tend to occur at lower elevations later in the day. A comparison with the region studied in the North American Monsoon Experiment (NAME) shows that similar diurnal patterns occur in the Sierra Madre Occidental region of Mexico. The population of precipitation features in both regions is similar, with the NAME region producing slightly larger precipitation systems on average than the southwest United States. Both regions on occasion demonstrate the pattern of convection initiating at high elevations and moving downslope while growing upscale through the afternoon and evening; however, there are also days on which convection remains over the high terrain. -

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an Evaluation of Population and Habitat Trends Version 3.0 2010

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an evaluation of population and habitat trends Version 3.0 2010 Isolated aspen stand. Photo by Heather McRae. Pygmy nuthatch. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Pumpkin Fire, Kaibab National Forest Mule deer. Photo by Bill Noble Red-naped sapsucker. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Northern Goshawk © Tom Munson Tree encroachment, Kaibab National Forest Prepared by: Valerie Stein Foster¹, Bill Noble², Kristin Bratland¹, and Roger Joos³ ¹Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest Supervisor’s Office ²Forest Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Supervisor’s Office ³Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Williams Ranger District Table of Contents 1. MANAGEMENT INDICATOR SPECIES ................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 Regulatory Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Management Indicator Species Population Estimates ...................................................... 10 SPECIES ACCOUNTS ................................................................................................ 18 Aquatic Macroinvertebrates ...................................................................................... 18 Cinnamon Teal .......................................................................................................... 21 Northern Goshawk ................................................................................................... -

IN PHOTOGRAPHS FEATURING the LANDSCAPES of EVERY COUNTY in ARIZONA “There in the Storm.” Is Even Peace

2015 FYI: THERE AREN’T ANY LOUSY PHOTOS IN THIS ISSUE AUGUST APACHE ESCAPE • EXPLORE • EXPERIENCE WOLVES THEY’RE SACRED TO THE TRIBE, BUT ... — VINCENT GOGH— VAN BEST OF AZ IN PHOTOGRAPHS FEATURING THE LANDSCAPES OF EVERY COUNTY IN ARIZONA “There in the storm.” is even peace San Francisco Peaks, Coconino County plus: CALIFORNIA CONDORS • TUMACÁCORI • O’LEARY PEAK • THE KAIBAB PLATEAU MEXICAN GARTERSNAKES • ICONIC PHOTOGRAPHER ALLEN REED • ARIZONA MOUNTAIN INN Kaibab Vermilion Cliffs Plateau Grand Canyon National Park CONTENTS 08.15 Tusayan Williams O’Leary Peak Flagstaff 2 EDITOR’S LETTER 3 CONTRIBUTORS PHOENIX 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 56 WHERE IS THIS? Tumacácori National Historical Park 5 THE JOURNAL POINTS OF INTEREST IN THIS ISSUE People, places and things from around the state, including a look back at iconic photographer Allen Reed, Tumacácori National Historical Park and the would-be toll road to the highest point in 44 Arizona. WING COMMANDER Chris Parish is a wildlife biologist for The Peregrine Fund. He’s 16 THE BEST OF ARIZONA well versed in many species, but he’s an expert on California If we were Texas Highways, we couldn’t do this portfolio — there condors. Among other things, the Flagstaff resident oversees the are too many counties (254) in Texas. In Arizona, however, where annual release of young condors over the Vermilion Cliffs. And his there are only 15, it’s a little easier to feature one of the scenic efforts are paying off. At last count, 74 of the rare birds were living wonders of every county in the state. -

The Guide North Rim Information and Maps

National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper North Rim 2013 Season The Guide North Rim Information and Maps Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! Most visitors experience Grand Canyon from viewpoints along the rim. From this expansive Welcome to Grand Canyon perspective, it is hard to see anything but a harshly spectacular and ruggedly beautiful S ITTING ATOP THE K AIBAB the cover of the forest. Visitors in the warns of winter snowstorms soon landscape. Manmade structures are often hard Plateau, 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400– spring may see remnants of winter in to come. Although only 10 miles to spot because they have such a minimal 2,750 m) above sea level with lush disappearing snowdrifts or temporary (16 km) as the raven flies from the footprint on the canyon’s grandeur. green meadows surrounded by a mountain lakes of melted snow. The South Rim, the North Rim offers a mixed conifer forest sprinkled with summer with colorful wildflowers and very different visitor experience. Far below the rim, hundreds of miles of river white-barked aspen, the North Rim is intense thunderstorms comes and goes Solitude, awe-inspiring views, a corridor and backcountry trails allow the an oasis in the desert. Here you may all too quickly, only to give way to the slower pace, and the feeling of going intrepid to experience a world without cell observe deer feeding, coyote chasing colors of fall. With the yellows and back in time are only a few of the phones, computers, or even electricity. -

Grand Canyon DECEMBER 2003

arizonahighways.com DECEMBER 2003 three ways to visit the grand canyon DECEMBER 2003 page 44 4 SPECIAL SECTION The Grand Canyon 56 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP Arizona’s centerpiece natural wonder is the Two brothers exchange Christmas gifts, but neither has extraordinary chasm in the state’s northwest quadrant, a clue who sent what to whom. where 4 million-plus visitors go each year for incomparable panoramas and outdoor experiences. This 53 HUMOR month, Arizona Highways examines the Canyon from the south, the complex internal floor and the north. 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL 50 DESTINATION Holy Trinity Monastery 8 South Rim At Holy Trinity, a Benedictine monastery in Most visitors head to this sprawling southeastern Arizona, visitors find silence, solitude escarpment for the dramatic views from a and a sense of peace. number of ideal and accessible observation points. 3 ALONG THE WAY The ringing and magic of silver bells at Christmastime linger on for those who want to hear. 20 The Challenge of 54 HIKE OF THE MONTH Interior Route-finding Brittlebush Trail Hikers on the boulder-strewn route in the Sonoran Deep in the tough gorges, the Redwall Desert National Monument south of Phoenix find a limestone formations pose daunting tests surprisingly remote landscape. to anyone who seeks a path through them. North Rim 32 [THIS PAGE] The last rays of the This out-of-the-way high plateau and setting sun envelop a lone hiker spectacular alpine environment create on a hazy day at Yaki Point in North Rim GRAND CANYON a haven for people and wildlife. -

NR 2011.Indd

LOOK INSIDE THIS GUIDE 2011 Season Look Inside 2 Plan Your Visit 5 Ranger-Led Programs 8 Park Map and Trail Guides 12 Hiking Information 14 Services Many More Answers to Your Questions... ...Look Inside North Rim Drive with care What Time Is It? Emergency: 911 • Observe posted speed limits. Most of Arizona, including Grand Canyon 24 hours-a-day dial • Maximum speed limit is 45 mph. National Park, remains on Mountain Standard 911 from any phone • Watch for pedestrians and wildlife. Time year-round. Arizona is on the same time • Increase caution at night and during wet as California and Nevada, and one hour behind 9-911 from hotel phones conditions. Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. What to do and Where to go in Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon Guide & Maps Grand Canyon National Park | North Rim Enjoy the North Rim Use this Guide to get the most out of your visit Personalize Your Grand Canyon Experience Welcome to There are many ways to experience Grand Canyon. Individual interests, available time, and weather can influence a the North Rim visit. Refer to the maps on pages 8-9 to locate the places mentioned below. Sitting atop the Kaibab Plateau 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400 - 2,750 Activity Comment m) above sea level with lush green Drop by the visitor center • Open 8:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. (9:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. after meadows surrounded by a mixed October 15) conifer forest sprinkled with white- • Talk with a ranger barked aspen, the North Rim is • Enjoy the interpretive exhibits an oasis in the desert.