AZWILD Fall 0506

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narbonapass.Pdf

FIRST-DAY ROAD LOG 1 FIRST-DAY ROAD LOG, FROM GALLUP TO GAMERCO, YAH-TA-HEY, WINDOW ROCK, FORT DEFIANCE, NAVAJO, TODILTO PARK, CRYSTAL, NARBONA PASS, SHEEP SPRINGS, TOHATCHI AND GALLUP SPENCER G. LUCAS, STEVEN C. SEMKEN, ANDREW B. HECKERT, WILLIAM R. BERGLOF, First-day Road Log GRETCHEN HOFFMAN, BARRY S. KUES, LARRY S. CRUMPLER AND JAYNE C. AUBELE ������ ������ ������ ������� ������ ������ ������ ������ �������� Distance: 141.8 miles ������� Stops: 5 ���� ������ ������ SUMMARY ������ �� ������ �� ����� �� The first day’s trip takes us around the southern �� �� flank of the Defiance uplift, back over it into the �� southwestern San Juan Basin and ends at the Hogback monocline at Gallup. The trip emphasizes Mesozoic— especially Jurassic—stratigraphy and sedimentation in NOTE: Most of this day’s trip will be conducted the Defiance uplift region. We also closely examine within the boundaries of the Navajo (Diné) Nation under Cenozoic volcanism of the Navajo volcanic field. a permit from the Navajo Nation Minerals Department. Stop 1 at Window Rock discusses the Laramide Persons wishing to conduct geological investigations Defiance uplift and introduces Jurassic eolianites near on the Navajo Nation, including stops described in this the preserved southern edge of the Middle-Upper guidebook, must first apply for and receive a permit Jurassic depositional basin. At Todilto Park, Stop 2, from the Navajo Nation Minerals Department, P.O. we examine the type area of the Jurassic Todilto For- Box 1910, Window Rock, Arizona, 86515, 928-871- mation and discuss Todilto deposition and economic 6587. Sample collection on Navajo land is forbidden. geology, a recurrent theme of this field conference. From Todilto Park we move on to the Green Knobs diatreme adjacent to the highway for Stop 3, and then to Stop 4 at the Narbona Pass maar at the crest of the Chuska Mountains. -

Arizona Forest Action Plan 2015 Status Report and Addendum

Arizona Forest Action Plan 2015 Status Report and Addendum A report on the strategic plan to address forest-related conditions, trends, threats, and opportunities as identified in the 2010 Arizona Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy. November 20, 2015 Arizona State Forestry Acknowledgements: Arizona State Forestry would like to thank the USDA Forest Service for their ongoing support of cooperative forestry and fire programs in the State of Arizona, and for specific funding to support creation of this report. We would also like to thank the many individuals and organizations who contributed to drafting the original 2010 Forest Resource Assessment and Resource Strategy (Arizona Forest Action Plan) and to the numerous organizations and individuals who provided input for this 2015 status report and addendum. Special thanks go to Arizona State Forestry staff who graciously contributed many hours to collect information and data from partner organizations – and to writing, editing, and proofreading this document. Jeff Whitney Arizona State Forester Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial On the second anniversary of the Yarnell Hill Fire, the State of Arizona purchased 320 acres of land near the site where the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots sacrificed their lives while battling one of the most devastating fires in Arizona’s history. This site is now the Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park. “This site will serve as a lasting memorial to the brave hotshots who gave their lives to protect their community,” said Governor Ducey. “While we can never truly repay our debt to these heroes, we can – and should – honor them every day. Arizona is proud to offer the public a space where we can pay tribute to them, their families and all of our firefighters and first responders for generations to come.” Arizona Forest Action Plan – 2015 Status Report and Addendum Background Contents The 2010 Forest Action Plan The development of Arizona’s Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy (now known as Arizona’s “Forest Action Plan”) was prompted by federal legislative requirements. -

Arizona Regional Haze 308

Arizona State Implementation Plan Regional Haze Under Section 308 Of the Federal Regional Haze Rule Air Quality Division January 2011 (page intentionally blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Overview of Visibility and Regional Haze..................................................................................2 1.2 Arizona Class I Areas.................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Background of the Regional Haze Rule ......................................................................................3 1.3.1 The 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Phase I Visibility Rules – The Arizona Visibility Protection Plan ..................................... 4 1.3.3 The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 4 1.3.4 Submittal of Arizona 309 SIP............................................................................................. 6 1.4 Purpose of This Document .......................................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 Basic Plan Elements.......................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: ARIZONA REGIONAL HAZE SIP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ......................... 15 2.1 Federal -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

KAIBAB DEER HERD MUST BE REDUCED IMMEDIATELY -- October 13,1924

U.S.DEPARTMENT OFAGRICULTURE Office of the Secretary , Pra serviq ” _, RELEASED FOR PUBLICATION, MONDAYMORNING, OCTOBER13, 19+: -9 KAIBAB DEER HERD MUST BE REDUCEDIXMEDIATELY Immediate reduction of the deer herd on the Kaibab National Forest in northern Arizona is strongly urged by the special committee appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture to study and report on the conditions existing on the Grand Canyon Game Preserve, announces the Forest Service, United States Depart- ment of Agricu&are. ! The special committee is composed of John B. Burnham, chairman, repre- senting the American Game Protective Association; Heyward Cutting, of tho Boone and Crockett Club; T. Gilbert Pearson,, of the Audubon Society and the National Parks Association; and T. W. Tomlinson, of the American National Livestock Association. This ccmmittee has made its report to the Secretary of Agriculture following a personal inspection of the Kaibab Plateau on which the Grand Canyon &me Preserve was estabZ.shed in 1906 by President Roosevelt. This area also forms part of the Kaibab Nakional Forest and is under the supervision Of the Forest Servi&. _ . , Upwards of 30,000 head of mule deer are now on the Kaibab Plateau, according to the report of the committee. This is fully twice as many deer as the vegetation can support and the entire herd is in imdnent danger of extinction through starvation unless reduced to a safety number. Moreover, the condition of That forage is still to be found on the ' arsa is far below nornal and several years will be required to grow new forage crops before the region can support more than 15,009 head of deer'in addition to the scattering amal 1 herds of domestic livest.ock owned by settlers living in and around the Kaibab Forest. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation

Rainfall-Runoff Model for Black Creek Watershed, Navajo Nation Item Type text; Proceedings Authors Tecle, Aregai; Heinrich, Paul; Leeper, John; Tallsalt-Robertson, Jolene Publisher Arizona-Nevada Academy of Science Journal Hydrology and Water Resources in Arizona and the Southwest Rights Copyright ©, where appropriate, is held by the author. Download date 25/09/2021 20:12:23 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/301297 37 RAINFALL-RUNOFF MODEL FOR BLACK CREEK WATERSHED, NAVAJO NATION Aregai Tecle1, Paul Heinrich1, John Leeper2, and Jolene Tallsalt-Robertson2 ABSTRACT This paper develops a rainfall-runoff model for estimating surface and peak flow rates from precipitation storm events on the Black Creek watershed in the Navajo Nation. The Black Creek watershed lies in the southern part of the Navajo Nation between the Defiance Plateau on the west and the Chuska Mountains on the east. The area is in the semiarid part of the Colorado Plateau on which there is about 10 inches of precipitation a year. We have two main purposes for embarking on the study. One is to determine the amount of runoff and peak flow rate generated from rainfall storm events falling on the 655 square mile watershed and the second is to provide the Navajo Nation with a method for estimating water yield and peak flow in the absence of adequate data. Two models, Watershed Modeling System (WMS) and the Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC) Hydrological Modeling System (HMS) that have Geographic Information System (GIS) capabilities are used to generate stream hydrographs. Figure 1. Physiographic map of the Navajo Nation with the Chuska The latter show peak flow rates and total amounts of Mountain and Deance Plateau and Stream Gaging Stations. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MARCH 4, 1999 No. 34 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE In this environment, it made sense to pro- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the vide a disincentive to an older generation of pore (Mr. HEFLEY). gentleman from Oregon (Mr. WU) come workers to remain in the work force. The gov- f forward and lead the House in the ernment would take care of this older genera- Pledge of Allegiance. tion by ensuring a level of financial support we DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Mr. WU led the Pledge of Allegiance now call a social insurance system. In turn, PRO TEMPORE as follows: new positions for younger workers were cre- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the ated, giving them the wherewithal to become fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- financially independent from government as- nication from the Speaker: lic for which it stands, one nation under God, sistance. Taxes from these workers would be- indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. WASHINGTON, DC, come the mechanism to fund the benefits pay- March 4, 1999. f ments to the retirees. I hereby appoint the Honorable JOEL ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER Sixty-five years later, it is time to revisit the HEFLEY to act as Speaker pro tempore on PRO TEMPORE premise underlying this penalty. -

Grand Canyon

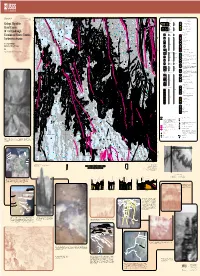

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Arizona's Wildlife Linkages Assessment

ARIZONAARIZONA’’SS WILDLIFEWILDLIFE LINKAGESLINKAGES ASSESSMENTASSESSMENT Workgroup Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Arizona’s Wildlife Linkages Assessment Prepared by: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Siobhan E. Nordhaugen, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Evelyn Erlandsen, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Habitat Branch Paul Beier, Northern Arizona University, School of Forestry Bruce D. Eilerts, Arizona Department of Transportation, Natural Resources Management Group Ray Schweinsburg, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Terry Brennan, USDA Forest Service, Tonto National Forest Ted Cordery, Bureau of Land Management Norris Dodd, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Research Branch Melissa Maiefski, Arizona Department of Transportation, Environmental Planning Group Janice Przybyl, The Sky Island Alliance Steve Thomas, Federal Highway Administration Kim Vacariu, The Wildlands Project Stuart Wells, US Fish and Wildlife Service 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT First Printing Date: December, 2006 Copyright © 2006 The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written consent from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written consent of the copyright holder. Additional copies may be obtained by submitting a request to: The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup E-mail: [email protected] 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT The Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup Mission Statement “To identify and promote wildlife habitat connectivity using a collaborative, science based effort to provide safe passage for people and wildlife” 2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT Primary Contacts: Bruce D. -

Sources of Pima County Water Quality Data

SOURCES OF PIMA COUNTY WATER QUALITY DATA Prepared by Pima Association of Governments November 1996 Pima Association of Governments PIMA ASSOCIATION OF GOVERNMENTS REGIONAL COUNCIL Chairman Vice-Chairman Treasurer Mike Boyd Shirley Villegas Paul Parisi Supervisor Mayor Vice-Mayor Pima County City of South Tucson Town of Oro Valley Member Member Member George Miller Ora Mae Ham Charles Oldham Mayor Councilmember Mayor City of Tucson Town of Marana T own of Sahuarita J Management Committee Hurvie Davis, Manager, Town of Marana Rene Gastelum, Manager, City of South Tucson Chuck Huckelberry, Administrator, Pima County Luis Gutierrez, Manager, City of Tucson Chuck Sweet, Manager, Town of Oro Valley Anne Parrish, Town of Sahuarita Executive Director Regional Planning Manager Thomas L. Swanson Gail F. Kushner Hydrologists Water Resources Technician Gregory S. Hess Cheryl Karrer Claire L. Zucker Support Staff Karen Bazinet Eleanor Salazar November 1996 Printed on Recycled Paper ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PAG appreciates the help of the following people who provided much of the information that is included in this document: Stuart Schillinger at Tucson Water; Nancy Ward and Karen Van Rijn with the City of Tucson Office of Environmental Management; John Schieffer at Pima County Wastewater Management Department; Susan Hess at Pima County Solid Waste Management; Byron McMillan at Pima County Department of Environmental Quality; Julia Fonseca at Pima County Flood Control District; Claire Logue, with Pima County Technical Services; Mike Block and Theresa Lutz with Metro Water District; Mary Simmerer, Lin Lawson, Patti Spindler, Marianne Gilbert and Steve Callaway at the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality; Jeff Tannler at the Arizona Department of Water Resources; Marc Dahlberg at Arizona Game and Fish; Steve Richard with the Arizona Geological Survey; and Chris Smith at the United States Geological Survey. -

You Can Learn More About the Chiricahuas

Douglas RANGER DISTRICT www.skyislandaction.org 2-1 State of the Coronado Forest DRAFT 11.05.08 DRAFT 11.05.08 State of the Coronado Forest 2-2 www.skyislandaction.org CHAPTER 2 Chiricahua Ecosystem Management Area The Chiricahua Mountain Range, located in the Natural History southeastern corner of the Coronado National Forest, The Chiricahua Mountains are known for their is one of the largest Sky Islands in the U.S. portion of amazing variety of terrestrial plants, animals, and the Sky Island region. The range is approximately 40 invertebrates. They contain exceptional examples of miles long by 20 miles wide with elevations ranging ecosystems that are rare in southern Arizona. While from 4,400 to 9,759 feet at the summit of Chiricahua the range covers only 0.5% of the total land area in Peak. The Chiricahua Ecosystem Management Area Arizona, it contains 30% of plant species found in (EMA) is the largest Management Area on the Forest Arizona, and almost 50% of all bird species that encompassing 291,492 acres of the Chiricahua and regularly occur in the United States.1 The Chiricahuas Pedragosa Mountains. form part of a chain of mountains spanning from Protected by remoteness, the Chiricahuas remain central Mexico into southern Arizona. Because of one of the less visited ranges on the Coronado their proximity to the Sierra Madre, they support a National Forest. Formerly surrounded only by great diversity of wildlife found nowhere else in the ranches, the effects of Arizona’s explosive 21st century United States such as the Mexican Chickadee, whose population growth are beginning to reach the flanks only known breeding locations in the country are in of the Chiricahuas.