You Can Learn More About the Chiricahuas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Coloration Anomaly of a Male Collared Trogon (Trogon Collaris)

Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie) ISSN: 0065-1737 [email protected] Instituto de Ecología, A.C. México Eisermann, Knut; Omland, Kevin Coloration anomaly of a male Collared Trogon (Trogon Collaris) Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), vol. 23, núm. 2, 2007, pp. 197-200 Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Xalapa, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57523211 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.) 23(2): 197-200 (2007) Nota Científica COLORATION ANOMALY OF A MALE COLLARED TROGON (TROGON COLLARIS) Resumen. Reportamos la observación de un macho adulto de Trogon collaris con vientre amarillo, similar al color del vientre de Trogon violaceus o Trogon melanocephalus. El pico era de color amarillo sucio y el anillo orbital era oscuro. Con base en publicaciones sobre coloración anormal en otras especies, asumimos que fueron alteraciones genéticas o de desarrollo del individuo las que causaron el color amarillo en lugar del rojo usual del plumaje ventral. Collared Trogon (Trogon collaris) occurs in several disjunct areas from central Mexico to the northern half of South America east of the Andes (AOU 1998. Check-list of North American birds. 7th ed. AOU. Washington D.C.). At least eight subspecies are recognized (Dickinson 2003. The Howard and Moore complete checklist of the birds of the world. 3rd ed. Princeton Univ. -

Evolution of Brilliant Iridescent Feather Nanostructures

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.31.446390; this version posted May 31, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Evolution of brilliant iridescent feather nanostructures 2 Klara K. Nordén1, Chad M. Eliason2, Mary Caswell Stoddard1 3 1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 4 08544, USA 5 2Grainger Bioinformatics Center, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA 6 7 Abstract 8 The brilliant iridescent plumage of birds creates some of the most stunning color displays 9 known in the natural world. Iridescent plumage colors are produced by nanostructures in 10 feathers and have evolved in a wide variety of birds. The building blocks of these 11 structures—melanosomes (melanin-filled organelles)—come in a variety of forms, yet how 12 these different forms contribute to color production across birds remains unclear. Here, we 13 leverage evolutionary analyses, optical simulations and reflectance spectrophotometry to 14 uncover general principles that govern the production of brilliant iridescence. We find that a 15 key feature that unites all melanosome forms in brilliant iridescent structures is thin melanin 16 layers. Birds have achieved this in multiple ways: by decreasing the size of the melanosome 17 directly, by hollowing out the interior, or by flattening the melanosome into a platelet. The 18 evolution of thin melanin layers unlocks color-producing possibilities, more than doubling 19 the range of colors that can be produced with a thick melanin layer and simultaneously 20 increasing brightness. -

Especies Vegetales En Peligro, Su Distribución Y Estatus De Conservación De Los Ecosistemas Donde Se Presentan

ESPECIES VEGETALES EN PELIGRO, SU DISTRIBUCIÓN Y ESTATUS DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LOS ECOSISTEMAS DONDE SE PRESENTAN ENDANGERED VEGETAL SPECIES, THEIR DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF THE ECOSYSTEMS IN WHICH THEY OCCUR Mario Humberto Royo-Márquez1, Alicia Melgoza-Castillo2 y Gustavo Quintana-Martínez2 RESUMEN En México, la norma oficial mexicana (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) integra especies de flora y fauna silvestres en riesgo, pero no especifica su distribución geográfica. Como base para la realización de planes de conservación en el estado de Chihuahua es importante identificar las plantas incluidas en dicha norma, otras que deberían integrarse por su distribución restringida y rareza, así como el estado de conservación de los ecosistemas donde se presentan. En este contexto, se revisó una base de datos de alrededor de 4 000 especies de la flora de la entidad; se consultó la literatura disponible; y se realizaron visitas a diversos herbarios. En total se documentaron 195 taxa, 59 con estatus según la NOM-059, pertenecientes a 40 géneros y 21 familias, de los cuales, 19 especies son endémicas para México. Además, se proponen 31 taxa de 23 géneros y nueve familias, para ser estudiadas y evaluar su posible incorporación en la Norma, ya que son endemismos locales o registros únicos para México. Se sugieren 105 especies consideradas como raras, incluidas en 76 géneros y 37 familias. Los bosques y pastizales presentan el mayor número de especies con estatus y la más grande superficie con vegetación secundaria, lo que indica que esos ecosistemas presentan diversos grados de deterioro. Se requieren estudios poblacionales de las especies propuestas para plantear estrategias de conservación y manejo sustentable de los ecosistemas donde se desarrollan. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

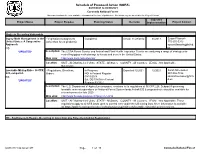

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes Fulgens Donald R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Department of Biology and Chemistry Chemistry 6-27-2018 Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens Donald R. Powers George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, and the Poultry or Avian Science Commons Recommended Citation Powers, Donald R., "Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens" (2018). Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry. 123. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rivoli's Hummingbird Eugenes fulgens Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Family: TROCHILIDAE Version: 2.1 — Published June 27, 2018 Donald R. Powers Introduction Rivoli's Hummingbird was named in honor of the Duke of Rivoli when the species was described by René Lesson in 1829 (1). Even when it became known that William Swainson had written an earlier description of this species in 1827, the common name Rivoli's Hummingbird remained until the early 1980s, when it was changed to Magnificent Hummingbird. In 2017, however, the name was restored to Rivoli's Hummingbird when the American Ornithological Society officially recognized Eugenes fulgens as a distinct species from E. spectabilis, the Talamanca Hummingbird, of the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama (2). See Systematics: Related Species. -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument

In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument Open-File Report 2008-1023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service This page left intentionally blank. In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt, William L. Halvorson, and Pamela Anning Open-File Report 2008-1023 U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B.F., Schmidt, C.A., Halvorson, W.L., and Anning, Pamela, 2008, Vascular plant and vertebrate inventory of Chiricahua National Monument: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1023, 104 p. [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1023/]. Cover photo: Chiricahua National Monument. Photograph by National Park Service. Note: This report supersedes Schmidt et al. (2005). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 88(1), 2013, pp. 116–126 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0276 Copyright © 2013 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene West Nile Virus Ecology in a Tropical Ecosystem in Guatemala Maria E. Morales-Betoulle,† Nicholas Komar,*† Nicholas A. Panella, Danilo Alvarez, Marı´aR.Lo´pez, Jean-Luc Betoulle, Silvia M. Sosa, Marı´aL.Mu¨ ller, A. Marm Kilpatrick, Robert S. Lanciotti, Barbara W. Johnson, Ann M. Powers, Celia Cordo´ n-Rosales, and the Arbovirus Ecology Work Group‡ Center for Health Studies, Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, Guatemala; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Arbovirus Disease Branch, Fort Collins, Colorado; University of California, Santa Cruz, California; Fundacio´n Mario Dary, Guatemala City, Guatemala; and Fundacio´n para el Ecodesarrollo, Guatemala City, Guatemala Abstract. West Nile virus ecology has yet to be rigorously investigated in the Caribbean Basin. We identified a transmission focus in Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, and established systematic monitoring of avian abundance and infec- tion, seroconversions in domestic poultry, and viral infections in mosquitoes. West Nile virus transmission was detected annually between May and October from 2005 to 2008. High temperature and low rainfall enhanced the probability of chicken seroconversions, which occurred in both urban and rural sites. West Nile virus was isolated from Culex quinquefasciatus and to a lesser extent, from Culex mollis/Culex inflictus, but not from the most abundant Culex mosquito, Culex nigripalpus. A calculation that combined avian abundance, seroprevalence, and vertebrate reservoir competence suggested that great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) is the major amplifying host in this ecosystem. -

Arizona Regional Haze 308

Arizona State Implementation Plan Regional Haze Under Section 308 Of the Federal Regional Haze Rule Air Quality Division January 2011 (page intentionally blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Overview of Visibility and Regional Haze..................................................................................2 1.2 Arizona Class I Areas.................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Background of the Regional Haze Rule ......................................................................................3 1.3.1 The 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Phase I Visibility Rules – The Arizona Visibility Protection Plan ..................................... 4 1.3.3 The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 4 1.3.4 Submittal of Arizona 309 SIP............................................................................................. 6 1.4 Purpose of This Document .......................................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 Basic Plan Elements.......................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: ARIZONA REGIONAL HAZE SIP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ......................... 15 2.1 Federal -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

Table of Contents

TABLEGUIDELINES OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 12: CONTACT INFORMATION AND MAPS 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………………….......122 12.2 BLM CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………......123 12.3 USFS CONTACT INFORMATION………………………………………………….....124 12.4 FHWA CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………....130 12.5 GIS INFORMATION..............................................................................................131 12.6 MAPS...................................................................................................................132 121 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION ADOT web link azdot.gov/ ADOT maps azdot.gov/maps General Information 602-712-7355 OFFICE ADOT DIRECTOR 602.712.7227 Deputy Director of Transportation 602.712.7391 Deputy Director of Policy 602.712.7550 Deputy Director of Business Operations 602.712.7228 Multimodal Planning Division (MPD) Director 602.712.7431 MPD Planning and Programming Director 602.712.8140 MPD Planning and Environmental Linkages Manager 602.712.4574 Infrastructure Delivery and Operations Division (IDO) 602.712.7391 State Engineer, Sr. Deputy State Engineer and Deputy State Engineer Offices 602.712.7391 DISTRICT ENGINEERS Northcentral azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northcentral 928.774.1491 Northeast azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northeast 928.524.5400 Central Construction District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.8965 Central Maintenance District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.6664 Northwest azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northwest 928.777.5861