114 New Zealand Journal of History, 43, 1 (2009) Has Been Reproduced Online, Although an Up-To-Date Version of Flash Is Useful F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA HERITAGE TRAIL MAIN FEATURES of the TRAIL: This Trail Will Take About Four Hours to Drive and View at an Easy TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA Pace

WELLINGTON’S TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA HERITAGE TRAIL MAIN FEATURES OF THE TRAIL: This trail will take about four hours to drive and view at an easy TE ARA O NGA TUPUNA pace. Vantage points are mostly accessible by wheelchair but there are steps at some sites such as Rangitatau and Uruhau pa. A Pou (carved post), a rock or an information panel mark various sites on the trail. These sites have been identified with a symbol. While the trail participants will appreciate that many of the traditional sites occupied by Maori in the past have either been built over or destroyed, but they still have a strong spiritual presence. There are several more modern Maori buildings such as Pipitea Marae and Tapu Te Ranga Marae, to give trail participants a selection of Maori sites through different periods of history. ABOUT THE TRAIL: The trail starts at the Pipitea Marae in Thorndon Quay, opposite the Railway Station, and finishes at Owhiro Bay on the often wild, southern coast of Wellington. While not all the old pa, kainga, cultivation and burial sites of Wellington have been included in this trail, those that are have been selected for their accessibility to the public, and their viewing interest. Rock Pou Information panel Alexander Turnbull Library The Wellington City Council is grateful for the significant contribution made by the original heritage Trails comittee to the development of this trail — Oroya Day, Sallie Hill, Ken Scadden and Con Flinkenberg. Historical research: Matene Love, Miria Pomare, Roger Whelan Author: Matene Love This trail was developed as a joint project between Wellingtion City Council, the Wellington Tenths Trust and Ngati Toa. -

Northern Mount Victoria Historical Society Walking Guide Tour (Alan Middleton- Olliver)

Northern Mount Victoria Historical Society Walking Guide Tour (Alan Middleton- Olliver) Captain C.W. Mein Smith's original map "Plan of the Town of Wellington, Port Nicholson, 14 August 1840" For the New Zealand Company established the basic street structure for Mount Victoria. Whereas southern Mount Victoria was an extension of the Te Aro flat grid street pattern, the steepness of the land in northern Mount Victoria, dictated some alteration to the grid pattern. The original streets of the suburb were Majoribanks, Pirie and Ellice in the east west direction, Brougham and Austin Streets and Kent Terrace in the north south direction, with Roxburgh, Mcfarlane, and Hawker streets and Clyde Quay in the northern area. The map also shows the proposed canal route along to the Basin and Hawker street going over the hill and joining onto Oriental Terrace, now Oriental Parade. Approximately 36 acres were surveyed and defined in the northern area. Initial building development was haphazard as some acres had been purchased by land speculators. Thomas Ward's 1891 Survey of Wellington map shows the number of streets and pedestrian lanes in Mount Victoria had increased from 10 to 27, and by 1933 there were 47. Studying the Street maps and examining the Wises Directories gives a good indication of the development of the streets. These streets were at varying widths, including pedestrian lanes, and resulted from the haphazard subdivision of the original acres and the peculiarities of local topography. Some streets began as small private pedestrian lanes, which were only taken over by the Council at a much later date. -

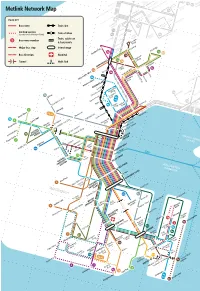

Metlink Network

1 A B 2 KAP IS Otaki Beach LA IT 70 N I D C Otaki Town 3 Waikanae Beach 77 Waikanae Golf Course Kennedy PNL Park Palmerston North A North Beach Shannon Waikanae Pool 1 Levin Woodlands D Manly Street Kena Kena Parklands Otaki Railway 71 7 7 7 5 Waitohu School ,7 72 Kotuku Park 7 Te Horo Paraparaumu Beach Peka Peka Freemans Road Paraparaumu College B 7 1 Golf Road 73 Mazengarb Road Raumati WAIKANAE Beach Kapiti E 7 2 Arawhata Village Road 2 C 74 MA Raumati Coastlands Kapiti Health 70 IS Otaki Beach LA N South Kapiti Centre A N College Kapiti Coast D Otaki Town PARAPARAUMU KAP IS I Metlink Network Map PPL LA TI Palmerston North N PNL D D Shannon F 77 Waikanae Beach Waikanae Golf Course Levin YOUR KEY Waitohu School Kennedy Paekakariki Park Waikanae Pool Otaki Railway ro 3 Woodlands Te Ho Freemans Road Bus route Parklands E 69 77 Muri North Beach 75 Titahi Bay ,77 Limited service Pikarere Street 68 Peka Peka (less than hourly, Monday to Friday) Titahi Bay Beach Pukerua Bay Kena Kena Titahi Bay Shops G Kotuku Park Gloaming Hill PPL Bus route number Manly Street71 72 WAIKANAE Paraparaumu College 7 Takapuwahia 1 Plimmerton Paraparaumu Major bus stop Train line Porirua Beach Mazengarb Road F 60 Golf Road Elsdon Mana Bus direction 73 Train station PAREMATA Arawhata Mega Centre Raumati Kapiti Road Beach 72 Kapiti Health 8 Village Train, cable car 6 8 Centre Tunnel 6 Kapiti Coast Porirua City Cultural Centre 9 6 5 6 7 & ferry route 6 H Coastlands Interchange Porirua City Centre 74 G Kapiti Police Raumati College PARAPARAUMU College Papakowhai South -

Te Aro Park, Actions Taken to Date and Potential Solutions

Executive Summary This report outlines safety concerns within Te Aro Park, actions taken to date and potential solutions. The numbers of events associated with social harm, occurring within the park are consistently higher in Te Aro Park than other central city parks. In order to improve safety within Te Aro Park the report outlines a number of options to address these issues, which have been categorised into projects for possible implementation over short, medium and long term and are outlined below. Short Term - as at January 2020 • Increased maintenance of the park – inclusion of Te Aro Park in the Central City Cleaning contract. • Removal of the canopy between the two toilet blocks and addition of directional lighting. • Lighting changes o If the canopy between the two toilets is not removed, additional lighting should be installed. o Vertical lighting should be installed on the Opera House side to improve night-time flow and a more defined route. o Lighting should also be added to the murals on the toilet building to increase attention to the artwork. o Lights should be added to the canopy of the Oaks building o Canopy lighting should be added to the tree. • Remove Spark phone booth as it creates blind spots and concealments. • Installing pedestrian crossings into both Manners and Dixon street to improve safe access to the park • Increase patrols to the Te Aro Park area during the hours of high activity and high social harm - this includes Police, Local Hosts and Maori Wardens • Improve guardianship of the park by involving businesses and other stakeholders in activity that occurs within the park, with central coordination from Council and intentional place-making Medium Term • Recognise and acknowledge the cultural significance of the park with interpretive signage and revitalise the park into more of a destination. -

New Zealand Redoubts, Stockades and Blockhouses, 1840–1848

New Zealand redoubts, stockades and blockhouses, 1840–1848 DOC SCIENCE INTERNAL SERIES 122 A. Walton Published by Department of Conservation P.O. Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand DOC Science Internal Series is a published record of scientific research carried out, or advice given, by Department of Conservation staff, or external contractors funded by DOC. It comprises progress reports and short communications that are generally peer-reviewed within DOC, but not always externally refereed. Fully refereed contract reports funded from the Conservation Services Levy (CSL) are also included. Individual contributions to the series are first released on the departmental intranet in pdf form. Hardcopy is printed, bound, and distributed at regular intervals. Titles are listed in the DOC Science Publishing catalogue on the departmental website http://www.doc.govt.nz and electronic copies of CSL papers can be downloaded from http://www.csl.org.nz © Copyright June 2003, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1175–6519 ISBN 0–478–224–29–X In the interest of forest conservation, DOC Science Publishing supports paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. This report was prepared for publication by DOC Science Publishing, Science & Research Unit; editing and layout by Ruth Munro. Publication was approved by the Manager, Science & Research Unit, Science Technology and Information Services, Department of Conservation, Wellington. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. General description 7 3. Main theatres and periods of construction 10 4. Distribution and regional variation 11 5. Survival and potential 11 6. Preliminary assessment of condition and potential 12 7. Conclusions 14 8. -

Oriental Bay Consultation February 2018

Oriental Bay consultation February 2018 229 public submissions received Submission Name On behalf of: Suburb Page 1 a as an individual Makara Beach 7 2 A Resident as an individual Oriental Bay 8 3 Aaron as an individual Island Bay 9 4 Adam as an individual Te Aro 10 5 Adam Kyne-Lilley as an individual Thorndon 11 6 Adrian Rumney as an individual Ngaio 12 7 aidy sanders as an individual Melrose 13 8 Alastair as an individual Aro Valley 14 9 Alex Dyer as an individual Island Bay 15 10 Alex Gough as an individual Miramar 17 11 Alexander Elzenaar as an individual Te Aro 18 12 Alexander Garside as an individual Northland 19 13 Alistair Gunn as an individual Other 20 14 Andrew Bartlett (again) as an individual Strathmore Park 21 15 Andrew Chisholm as an individual Brooklyn 22 16 Andrew Gow as an individual Brooklyn 23 17 Andrew McCauley as an individual Hataitai 24 18 Andrew R as an individual Newtown 25 19 Andy as an individual Mount Victoria 26 20 Andy C as an individual Ngaio 27 Andy Thomson, President Oriental Bay Residents Oriental Bay Residents 21 Association Association Not answered 28 22 Anita Easton as an individual Wadestown 30 23 Anonymous as an individual Johnsonville 31 24 Anonymous as an individual Miramar 32 25 Anonymous regular user as an individual Khandallah 33 26 Anoymas as an individual Miramar 34 27 Anthony Grigg as an individual Oriental Bay 35 28 Antony as an individual Wellington Central 36 29 Ashley as an individual Crofton Downs 37 30 Ashley Dunstan as an individual Kilbirnie 38 31 AShley Koning as an individual Strathmore -

On Let's Get Wellington Moving

Have your say… on Let’s Get Wellington Moving PUBLIC FEEDBACK IS OPEN UNTIL FRIDAY 15 DECEMBER 2017 Getting Wellington moving Let’s Get Wellington Moving is a joint initiative WHAT WILL WE DO WITH YOUR between Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington HOW DO I PROVIDE FEEDBACK? FEEDBACK? Regional Council and the New Zealand Transport • Go to getwellymoving.co.nz and fill in the We will consider all feedback and report this Agency. Our focus is the area from Ngauranga online survey Gorge to the airport, encompassing the Wellington back to you by March 2018. If you provide your Urban Motorway and connections to the central city, • Complete and return the freepost feedback contact details, we can send you the link or a copy Wellington Hospital and the eastern and southern form on the back page of this leaflet of the report. suburbs. • If you have difficulty completing the form We‘ll use your feedback to help develop a preferred We are working with the people of Wellington you can call us on (04) 499 4444 and we will scenario. This could be one of the four scenarios or a to develop a transport system that supports help you. new one that includes parts of the scenarios we are presenting now. The preferred scenario will include your aspirations for how the city looks, feels and You can also talk to us in person at: functions. The programme partners want to support more information on timing and cost. Wellington’s growth while making it safer and easier LOWER HUTT, Walter Nash Centre There will be more opportunities to have your say for you to get around. -

WADESTOWN SCHOOL Community Newsletter

WADESTOWN SCHOOL Community Newsletter Principal: Sally Barrett Website: www.wadestown.school.nz Thursday, 22 August 2019 Dear Parents On Thursday 8th August the staff and Wadestown School Whanau Group met for a Hui in the school hall. We enjoyed a fantastic professional development session with the Whanau Group. All our students will be learning the Wadestown School Pepeha which was developed at this hui and it appears below for your information. A special thank you go to Fiona McHardy, Huia Forbes, Fiona Shrapnell and Robin Paratene from the Whanau Group for facilitating this session and to our lead teachers of Te Reo Amber Pullin and Nicki Greer for arranging this very successful Hui. Update from the Whanau Group Tenā rā koutou katoa ngā whānau whānui o Wadestown Kura, On 8 July, Te Roopu Whanau (the Wadestown school whanau group) enjoyed sharing examples of personal pepeha with the school staff, and in return school staff shared their personal pepeha with the group. A pepeha is a statement of identity. It is a tribal saying and how Māori introduce themselves on the marae or in a formal setting, yet it is a formula that can be used by all people. A pepeha recites the whakapapa or genealogy of a person. The whanau group has suggested the following very simple ‘Wadestown School Pepeha’ as an important way for students, staff and whanau to collectively introduce themselves when representing Wadestown School. It is not intended to replace any personal pepeha, but provides a way for all Wadestown School whanau to connect with each other and others in this important way. -

Wellington Earthquake-Prone Buildings

List of Earthquake Prone Buildings as at 11 March 2011 WCC has assessed and confirmed that the buildings listed below are earthquake prone under the Building Act 2004. A section 124 notice has been issued to the owners of these buildings. Please note: The status of buildings in this list can change on a day to day basis and the information was current on the date the list was published. Please contact the Council for up to date information on individual properties or we would suggest you obtain a Land Information Memorandum (LIM). Street Name Street Number Suburb AKA Abel Smith Street 24 Te Aro Adelaide Road 114-116 Mt Cook Adelaide Road 191 Newtown Adelaide Road 381 Newtown Alfred Street 5 Mt Cook Arney Street 4 Bldg B Newtown East building Arney Street 4 Bldg A Newtown West building Aro Street 88 Bldg A Aro Valley East building Avon Street 25 Island Bay Bowen Street 25 Wellington Central Brussels Street 47 Miramar Cable Street 2 Te Aro 119 Jervois Quay Cambridge Terrace 53A Te Aro Cleveland Street 37 Brooklyn College Street 12 Te Aro Constable Street 77 Newtown Courtenay Place 43 Te Aro Courtenay Place 30 Te Aro Courtenay Place 33 Bldg B Te Aro Rear building Courtenay Place 45 Te Aro Courtenay Place 49 Te Aro Courtenay Place 66-72 Te Aro Courtenay Place 128 Te Aro Courtenay Place 132 Te Aro Courtenay Place 38 Te Aro Courtenay Place 55 Bldg B Te Aro Cnr Tory St & Forresters Ln Courtenay Place 55 Bldg A Te Aro Cnr Tory St & Courtenay Pl Courtenay Place 33 Bldg A Te Aro Building facing street Coutts Street 117 Kilbirnie 36 Te Whiti St -

Brooklyn-Tattler-February-2017

FEBRUARY 2017 284 BROOKLYN TATTLER what’s happening in your community What’s On Community news From the Library scouts Upstream arts trail Community Groups Artworks, and features a number of former In thIs IssUE from the bowling club members including the late Sir Coordinator/BCA 2-3 Leonard Hadley who was a life member and bCa News Brooklyn village is buzzing again after a long-time club patron. In the mural above From the Councillor 4 coordInatOr quiet Christmas and New Year period. EUan harrIs the bowlers is a commentary box with bowls I sure missed the smell of Jo’s pies as I Vogelmorn Tennis Club 5 brookLyn commUnIty centrE & commentators Garry Ward and Stuart Scott. walked through the village with my dog Residents Association 6 vogelmOrn hall ph 384 6799 Underneath you can make out flags for the Kodak. Arvind Mora from Brooklyn [email protected] Rose and Crown and Lovelocks Sports Bar. Scouts 8 Foodmarket and the team at Caribe kept Hi Everyone, The Lovelocks Sports Bar is still going strong the energy of the village going while From the Library 9 at 12 Bond Street but the Rose and Crown Welcome to the first Tattler for 2017 many took a break. Of course it was extra What’s On 10-11 pub in the former BNZ shopping centre on delivered free to homes throughout busy at the Brooklyn Community Centre Willis Street has now gone. Resource Centre News 12 Brooklyn, Kowhai Park, Panorama Heights, with the holiday program running. Friends of Owhiro Stream 14 Mornington, Vogeltown and Kingston, thanks to our neighbours the Brooklyn In late January I learned that Graeme BCA 15-17 Scout Group on Harrison Street. -

Wellington City Council - Spatial Plan

Wellington City Council - Spatial Plan Three Waters Assessment - Growth Catchments Mahi Table and Cost Estimates March 2021 Document History Activity Name Signature Date Author Katrina Murison 10/03/2021 Reviewed Mohammed Hassan 10/03/2021 Approved Olena Chan 11/03/2021 Version Date Description A 15/02/2021 Draft for WWL review B 18/02/2021 Draft for WCC review 0 10/03/2021 Final for WCC 1 Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Context and Scope ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Assumptions .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Three-Water Investment to Support Growth .................................................................................................... 4 2.1. Explaining Growth Investment .................................................................................................................. 4 2.2. Comparative investment by suburb .......................................................................................................... 5 3. Three-Water Mahi Catchments and Tables ....................................................................................................... 8 3.1. Growth Catchments .................................................................................................................................. -

WADESTOWN SCHOOL Community Newsletter

WADESTOWN SCHOOL Community Newsletter Principal: Sally Barrett Website: www.wadestown.school.nz Thursday 29 June, 2017 Dear Parents A Special Thank You from Us All to Our Wonderful PTA Volunteers I would to begin this last school Community Newsletter for the term by acknowledging the tremendous contribution of our two outgoing PTA co-chairs, Katy Pearce and Kirsty Bennett. Both Katy and Kirsty have worked tirelessly for Wadestown School over the last four years. They have been involved in a variety of innovative fundraising activities, welcoming new families to Wadestown School and led many other PTA initiatives. Under their skilled leadership the PTA has flourished and grown. Katy and Kirsty will be remembered for their positive attitude, superb organisational skills and ensuring that every PTA initiative they have undertaken has always benefitted the students of Wadestown School. What an amazing contribution you have both made. David Dick, our long-serving PTA treasurer is also standing down after a superb contribution, not only as our treasurer but being involved in many other PTA activities including several years of assisting with the mid-year social fundraisers. This year was no exception and David played a significant role in the success of the Kiwiana Party. David has also taken a leading role in emergency management at Wadestown School and assisted us by purchasing and preparing a kit for each area of the school with tools and equipment that would be required in an emergency. Thank you David for your commitment and support. Anna Sims has been a very dedicated supporter of the PTA and has undertaken many varied roles over the years she has been so actively involved.