Sociology Contributions to Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

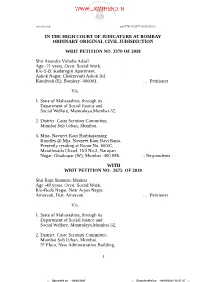

IN the HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 of 2018 Shri Anandra Vitho

spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 OF 2018 Shri Anandra Vithoba Adsul Age -71 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-5-B, Kadamgiri Apartment, Ashok Nagar, Chakravarti Ashok Rd, Kandivali (E), Bombay- 400001. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents WITH WRIT PETITION NO. 2675 OF 2019 Shri Raju Shamrao Mankar Age -49 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-Boda Nagar, Near Arjun Nagar, Amravati, Dist. Amravati. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. th 5 Floor, New Administrative Building, 1 ::: Uploaded on - 08/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 08/06/2021 13:37:37 ::: spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc Bandra, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents --- WITH WRIT PETITION (LDG.) NO. 9426 OF 2020 Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Age-35 years, Occu. Social Work. R/at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086 At present residing at - Ganga Savitri Banglow, Plot No. -

203Rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle

203rd Anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon Battle drishtiias.com/printpdf/203rd-anniversary-of-the-bhima-koregaon-battle Why in News The victory pillar (also known as Ranstambh or Jaystambh) in Bhima-Koregaon village (Pune district of Maharashtra) celebrated the 203rd anniversary of the Bhima- Koregaon battle of 1818 on 1st January, 2021. In 2018, incidents of violent clashes between Dalit and Maratha groups were registered during the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Bhima-Koregaon battle. Key Points 1/2 Historical Background: A battle was fought in Bhima Koregaon between the Peshwa forces and the British on 1st January, 1818. The British army, which comprised mainly of Dalit soldiers, fought the upper caste-dominated Peshwa army. The British troops defeated the Peshwa army. Peshwa Bajirao II had insulted the Mahar community and terminated them from the service of his army. This caused them to side with the English against the Peshwa’s numerically superior army. Mahar, caste-cluster, or group of many endogamous castes, living chiefly in Maharashtra state and in adjoining states. They mostly speak Marathi, the official language of Maharashtra. They are officially designated Scheduled Castes. The defeat of Peshwa army was considered to be a victory against caste-based discrimination and oppression. It was one of the last battles of the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817-18), which ended the Peshwa domination. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s visit to the site on 1st January, 1927, revitalised the memory of the battle for the Dalit community, making it a rallying point and an assertion of pride. The Victory Pillar Memorial: It was erected by the British in Perne village in the district for the soldiers killed in the Koregaon Bhima battle. -

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

403 Little Magazines in India and Emergence of Dalit

Volume: II, Issue: III ISSN: 2581-5628 An International Peer-Reviewed Open GAP INTERDISCIPLINARITIES - Access Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies LITTLE MAGAZINES IN INDIA AND EMERGENCE OF DALIT LITERATURE Dr. Preeti Oza St. Andrew‘s College Mumbai University [email protected] INTRODUCTION As encyclopaedia Britannica defines: ―Little Magazine is any of various small, usually avant-garde periodicals devoted to serious literary writings.‖ The name signifies most of all a usually non-commercial manner of editing, managing, and financing. They were published from 1880 through much of the 20th century and flourished in the U.S. and England, though French and German writers also benefited from them. HISTORY Literary magazines or ‗small magazines‘ are traced back in the UK since the 1800s. Americas had North American Review (founded in 1803) and the Yale Review(1819). In the 20th century: Poetry Magazine, published in Chicago from 1912, has grown to be one of the world‘s most well-regarded journals. The number of small magazines rapidly increased when the th independent Printing Press originated in the mid 20 century. Small magazines also encouraged substantial literary influence. It provided a very good space for the marginalised, the new and the uncommon. And that finally became the agenda of all small magazines, no matter where in the world they are published: To promote literature — in a broad, all- encompassing sense of the word — through poetry, short fiction, essays, book reviews, literary criticism and biographical profiles and interviews of authors. Little magazines heralded a change in literary sensibility and in the politics of literary taste. They also promoted alternative perspectives to politics, culture, and society. -

Dalit Literature and Aesthetics

Kervan – International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies n. 19 (2015) Dalit Literature and Aesthetics Ajay Navaria In conversation with Alessandra Consolaro, Dr. Ajay Navaria, who was in Torino as Visiting Researcher during October and November 2015, discusses Dalit literature and its aesthetics. Dr. Ajay Navaria, could you clarify the definition of the word ‘dalit’ and its different meanings? It’s not clear when and who and where the word ‘dalit’ was used for the first time. Late Gandhi ji called this community ‘Harijans’ – meaning People of God – but Doctor Ambedkar was against this word. He asked Gandhi ji “what else are the caste Hindus, if they themselves, like all of us, aren’t people of God”. Dr Ambedkar in his writings always used “depressed classes”, the word for this class of people or untouchables or depressed classes. In 1970, the word ‘dalit’ emerged in the Indian State of Maharastra, simultaneously with the movement of the Dalit panthers – a movement modeled to the US Black panther movement; Baburao Bagul, Nam Dev Dasal, Raja Dhale were the pioneers of this movement. This form of Dalit activism triggered/motivated the dalit literary moment we know today, as well its literature in Marathi language. So we can say that the word ‘dalit’ was used initially in Maharashtra. And from there it gradually migrated to the Hindi-belt of North-India in 1990. The word ‘dalit’ in Sanskrit means ‘broken’ or ‘scattered’. In Hindi dictionaries, the word ‘dalit’ means crushed, exploited, tortured and broken. As I said, the beginning of the Dalit movement has been considered from Dr Ambedkar. -

Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78)

FAMINE, DISEASE, MEDICINE AND THE STATE IN MADRAS PRESIDENCY (1876-78). LEELA SAMI UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: U5922B8 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592238 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION OF NUMBER OF WORDS FOR MPHIL AND PHD THESES This form should be signed by the candidate’s Supervisor and returned to the University with the theses. Name of Candidate: Leela Sami ThesisTitle: Famine, Disease, Medicine and the State in Madras Presidency (1876-78) College: Unversity College London I confirm that the following thesis does not exceed*: 100,000 words (PhD thesis) Approximate Word Length: 100,000 words Signed....... ... Date ° Candidate Signed .......... .Date. Supervisor The maximum length of a thesis shall be for an MPhil degree 60,000 and for a PhD degree 100,000 words inclusive of footnotes, tables and figures, but exclusive of bibliography and appendices. Please note that supporting data may be placed in an appendix but this data must not be essential to the argument of the thesis. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Dalit and Adivasi Voices in Hindi Literature

Studia Neophilologica ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/snec20 From marginalisation to rediscovery of identity: Dalit and Adivasi voices in Hindi literature Heinz Werner Wessler To cite this article: Heinz Werner Wessler (2020): From marginalisation to rediscovery of identity: Dalit and Adivasi voices in Hindi literature, Studia Neophilologica, DOI: 10.1080/00393274.2020.1751703 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2020.1751703 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 03 Jun 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=snec20 STUDIA NEOPHILOLOGICA https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2020.1751703 ARTICLE From marginalisation to rediscovery of identity: Dalit and Adivasi voices in Hindi literature Heinz Werner Wessler Department of Linguistics and Philology, University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Social issues have been an important concern in modern Indian Received 28 February 2019 literature in general and Hindi literature in particular since its begin- Accepted 10 October 2019 nings in the 19th century. In recent decades, Dalit and Adivasi KEYWORDS – literature written by author coming from a low caste and tribal Dalit; Indian literature; Hindi; background – have emerged as important Hindi genres. Dalit and caste in India; Adivasi; Indian Adivasis form the economically most marginalised groups in India. tribal literature; Dalit Their short stories, poems and essays, as well as autobiographical literature texts, are regularly published in important Hindi literary journals. -

Autobiography As a Social Critique: a Study of Madhopuri's Changiya Rukh and Valmiki's Joothan

AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN A Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy in Comparative Literature BY Kamaljeet kaur Administrative Guide: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. Amandeep Singh Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda March, 2012 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled ‘‘AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN’’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Administrative Guide, Acting Dean, School of Languages, Literature and Culture and Dr. Amandeep Singh, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Kamaljeet Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: i CERTIFICATE I certify that KAMALJEET KAUR has prepared her dissertation entitled “AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN”, for the award of M.Phil. degree of the Central University of Punjab, under my guidance. She has carried out this work at the Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. Amandeep Singh) Assistant Professor Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Acting Dean Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

District Census Handbook, North Goa

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 6 GOA DISTRICT CENSUS HAND BOOK PART XII-A AND XII-B VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY AND VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT NORTH GOA DISTRICT S. RAJENDRAN DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, GOA 1991 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS OF GOA ( All the Census Publications of this State will bear Series No.6) Central Government Publications Part Administration Report. Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration. (For Official use only). Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation. Part II General Population Tables Part II-A General Population Tables-A- Series. Part II-B Primary Census Abstract. Part III General Economic Tables Part III-A B-Series tables '(B-1 to B-5, B-l0, B-II, B-13 to B -18 and B-20) Part III-B B-Series tables (B-2, B-3, B-6 to B-9, B-12 to B·24) Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part IV-A C-Series tables (Tables C-'l to C--6, C-8) Part IV -B C.-Series tables (Table C-7, C-9, C-lO) Part V Migration Tables Part V-A D-Series tables (Tables D-l to D-ll, D-13, D-15 to D- 17) Part V-B D- Series tables (D - 12, D - 14) Part VI Fertility Tables F-Series tables (F-l to F-18) Part VII Tables on Houses and Household Amenities H-Series tables (H-I to H-6) Part VIII Special Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled SC and ST series tables Tribes (SC-I to SC -14, ST -I to ST - 17) Part IX Town Directory, Survey report on towns and Vil Part IX-A Town Directory lages Part IX-B Survey Report on selected towns Part IX-C Survey Report on selected villages Part X Ethnographic notes and special studies on Sched uled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part XI Census Atlas Publications of the Government of Goa Part XII District Census Handbook- one volume for each Part XII-A Village and Town Directory district Part XII-B Village and Town-wise Primary Census Abstract GOA A ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS' 1991 ~. -

History of Modern Maharashtra (1818-1920)

1 1 MAHARASHTRA ON – THE EVE OF BRITISH CONQUEST UNIT STRUCTURE 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Political conditions before the British conquest 1.3 Economic Conditions in Maharashtra before the British Conquest. 1.4 Social Conditions before the British Conquest. 1.5 Summary 1.6 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES : 1 To understand Political conditions before the British Conquest. 2 To know armed resistance to the British occupation. 3 To evaluate Economic conditions before British Conquest. 4 To analyse Social conditions before the British Conquest. 5 To examine Cultural conditions before the British Conquest. 1.1 INTRODUCTION : With the discovery of the Sea-routes in the 15th Century the Europeans discovered Sea route to reach the east. The Portuguese, Dutch, French and the English came to India to promote trade and commerce. The English who established the East-India Co. in 1600, gradually consolidated their hold in different parts of India. They had very capable men like Sir. Thomas Roe, Colonel Close, General Smith, Elphinstone, Grant Duff etc . The English shrewdly exploited the disunity among the Indian rulers. They were very diplomatic in their approach. Due to their far sighted policies, the English were able to expand and consolidate their rule in Maharashtra. 2 The Company’s government had trapped most of the Maratha rulers in Subsidiary Alliances and fought three important wars with Marathas over a period of 43 years (1775 -1818). 1.2 POLITICAL CONDITIONS BEFORE THE BRITISH CONQUEST : The Company’s Directors sent Lord Wellesley as the Governor- General of the Company’s territories in India, in 1798.