I. Definition, Methodology and Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macro Report August 23, 2004

Prepared by: LI Pang-kwong, Ph.D. Date: 10 April 2005 Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 2: Macro Report August 23, 2004 Country: Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, CHINA Date of Election: 12 September 2004 NOTE TO COLLABORATORS: The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Part I: Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1. Report the number of portfolios (cabinet posts) held by each party in cabinet, prior to the most recent election. (If one party holds all cabinet posts, simply write "all".) In the context of Hong Kong, the Executive Council (ExCo) can be regarded as the cabinet. The ExCo comprises the Official Members (all the Principal Officials in the Government Secretariat have been appointed concurrently the Official Members of the ExCo since July 2002) and the Non-official Members. The members of the ExCo are appointed by the Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), while the Principal Officials are nominated by the Chief Executive and are appointed by the Central People’s Government of China. Name of Political Party Number of Portfolios Official Members (with portfolios) of the Executive Council: All the Official Members do not have party affiliation. Non-official Members (without portfolio) of the Executive Council: 1. Democratic Alliance for Betterment of Hong Kong 1 2. -

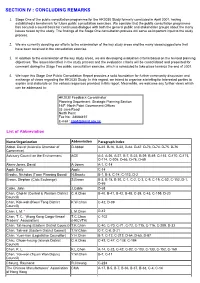

Section Iv : Concluding Remarks

SECTION IV : CONCLUDING REMARKS 1. Stage One of the public consultation programme for the HK2030 Study formally concluded in April 2001, having established a benchmark for future public consultation exercises. We consider that the public consultation programme has secured a sound basis for continuous dialogue with both the general public and stakeholder groups about the many issues raised by the study. The findings of the Stage One consultation process will serve as important input to the study process. 2. We are currently devoting our efforts to the examination of the key study areas and the many ideas/suggestions that have been received in the consultation exercise. 3. In addition to the examination of the key study areas, we are developing evaluation criteria based on the revised planning objectives. The issues identified in the study process and the evaluation criteria will be consolidated and presented for comment during the Stage Two public consultation exercise, which is scheduled to take place towards the end of 2001. 4. We hope this Stage One Public Consultation Report provides a solid foundation for further community discussion and exchange of views regarding the HK2030 Study. In this regard, we intend to organise a briefing for interested parties to explain and elaborate on the various responses provided in this report. Meanwhile, we welcome any further views which can be addressed to: HK2030 Feedback Co-ordinator Planning Department, Strategic Planning Section 16/F. North Point Government Offices 33 Java Road North Point Fax -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

A Chinese Graphic Design History in Greater China Since 1979 Wendy Siuyi Wong

Detachment and Unification: A Chinese Graphic Design History in Greater China Since 1979 Wendy Siuyi Wong The illustrations are identified by the name of Introduction designer, the client or title of the work, the The history of modern Chinese design is virtually unknown due to design category, and the year. The title of the its relatively late development compared to design in the West. Not work is the author’s own title, if an official until recent decades, since the opening up of China in 1979, has a name is cannot found. All woks reprinted with unifying Chinese graphic design history started to form. This was permission of the designer. assisted by China’s rapid economic development and interactions with Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau; which, together with main- land China, make up the Greater China region. Traditionally, in academic practice, it was common to separate the investigation of these individual Chinese societies. Matthew Turner, one of the few Western historians to examine Chinese design, notes that the history of Hong Kong design prior to the 1960s “simply was believed not to 1 2 1 Matthew Turner, “Early Modern Design in exist.” Chinese-trained design scholar Shou Zhi Wong emphasizes Hong Kong” in Dennis P. Doordan, ed., that there has been very little written about modern design in main- Design History: An Anthology land China, because design activity under the communists before (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995), 212. This the start of the Open Door Policy in 1979 was mostly in the service article was first published in Design of party propaganda.3 Both Turner and Wang, as well as Scott Issues, 6:1 (Fall 1989): 79–91; also Matthew Turner, “Development and Minick and Jiao Ping, published their works on Chinese design Transformations in the Discourse of history before a number of key economic and political changes in Design in Hong Kong” in Rajeshwari China and Hong Kong took place. -

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS for GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5Pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday)

2012 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ELECTION NOMINATIONS FOR GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCIES (NOMINATION PERIOD: 18-31 JULY 2012) As at 5pm, 26 July 2012 (Thursday) Geographical Date of List (Surname First) Alias Gender Occupation Political Affiliation Remarks Constituency Nomination Hong Kong Island SIN Chung-kai M Politician The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 YEUNG Sum M The Honorary Assistant Professor The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHAI Man-hon M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 CHENG Lai-king F Registered Social Worker The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 LEUNG Suk-ching F District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 HUI Chi-fung M District Council Member The Democratic Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island HUI Ching-on M Legal and Financial Consultant 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island IP LAU Suk-yee Regina F Chairperson/Board of Governors New People's Party 18/7/2012 WONG Chor-fung M Public Policy Researcher New People's Party 18/7/2012 TSE Tsz-kei M Community Development Officer New People's Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Kin-yee Miriam F Solicitor Liberal Party 18/7/2012 SHIU Ka-fai M Managing Director Liberal Party 18/7/2012 LEE Chun-keung Michael M Manager Liberal Party 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LO Wing-lok M Medical Practitioner 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island LAU Gar-hung Christopher M Retirement Benefits Consultant People Power 18/7/2012 SHIU Yeuk-yuen M Company Director 18/7/2012 AU YEUNG Ying-kit Jeff M Family Doctor 18/7/2012 Hong Kong Island CHUNG Shu-kun Christopher Chris M Full-time District Councillor Democratic Alliance -

Milestones of Tobacco Control in Hong Kong 向「全面禁煙」目標進發 Prospect for a Tobacco Endgame 27 香港吸煙情況 Smoking Prevalence in Hong Kong

目錄 CONTENTS 04 前言 46 香港吸煙與健康委員會的發展 Foreword Development of Hong Kong Council on Smoking and Health 06 獻辭 全力邁向無煙香港 Messages 57 Towards a Tobacco Endgame in Hong Kong 香港控煙重要里程 全球控煙趨勢 24 Global trend of tobacco control Milestones of Tobacco Control in Hong Kong 向「全面禁煙」目標進發 Prospect for a tobacco endgame 27 香港吸煙情況 Smoking Prevalence in Hong Kong 30 控煙工作多管齊下 Multi-pronged Tobacco Control Measures 監測煙草使用與預防政策 Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies 保護人們免受煙草煙霧危害 Protect people from tobacco smoke 提供戒煙幫助 Offer help to quit tobacco use 警示煙草危害 Warn about the dangers of tobacco 確保禁止煙草廣告、促銷和贊助 Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship 提高煙稅 Raise taxes on tobacco 前言 FOREWORD 2017 marks the 35th anniversary of tobacco control and also the decennial of the indoor smoking ban in Hong Kong. Through the concerted efforts of the Government and different sectors of the community for more than 30 years, the general public are aware of the health hazards of smoking and a supportive atmosphere for smoking cessation has been successfully created across the territory. The Smoking (Public Health) Ordinance was enacted in 1982, a key milestone for tobacco control legislation in Hong Kong. Since its enactment, the Government has adopted a progressive and multi-pronged approach on tobacco control which aligns with the MPOWER measures suggested by the World Health Organization. The smoking prevalence in Hong Kong has gradually reduced from 23.3% in the early 1980s to 10.5% in 2015, which is one of the lowest in the world. Thirty-five years ago, both indoor and outdoor places were smoky and hazy. -

01 China's Stockmarket

CHINA’S STOCKMARKET OTHER ECONOMIST BOOKS Guide to Analysing Companies Guide to Business Modelling Guide to Economic Indicators Guide to the European Union Guide to Financial Markets Guide to Management Ideas Numbers Guide Style Guide Business Ethics Economics E-Commerce E-Trends Globalisation Measuring Business Performance Successful Innovation Successful Mergers Wall Street Dictionary of Business Dictionary of Economics International Dictionary of Finance Essential Director Essential Finance Essential Internet Essential Investment Pocket Asia Pocket Europe in Figures Pocket World in Figures CHINA’S STOCKMARKET A Guide to its Progress, Players and Prospects Stephen Green To my family and friends THE ECONOMIST IN ASSOCIATION WITH PROFILE BOOKS LTD Published by Profile Books Ltd 3a Exmouth House, Pine Street, London ec1r 0jh Copyright © The Economist Newspaper Ltd 2003 Text copyright © Stephen Green 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. The greatest care has been taken in compiling this book. However, no responsibility can be accepted by the publishers or compilers for the accuracy of the information presented. Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily coincide -

Minutes of the 7Th Meeting of the Vetting Committee Eastern District Council

Minutes of the 7th Meeting of the Vetting Committee Eastern District Council Date : 28 February 2017 (Tuesday) Time : 2:30 pm Venue: Eastern District Council (EDC) Conference Room Present Time of Arrival Time of Departure (pm) (pm) Mr TING Kong-ho, Eddie 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Chi-chung, Dominic 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Chun-sing, Patrick 2:30 end of meeting Mr KU Kwai-yiu 2:30 end of meeting Mr HO Ngai-kam, Stanley 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAM Sum-lim 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAM Kei-tung, George 2:30 3:30 Mr HUNG Lin-cham 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHUI Chi-kin 2:45 end of meeting Mr CHEUNG Kwok-cheong, Howard 2:35 end of meeting Mr LEUNG Siu-sun, Patrick 2:30 end of meeting Mr LEUNG Kwok-hung, David 2:30 end of meeting Mr MAK Tak-ching 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Kin-pan, BBS, MH, JP 2:30 4:10 Mr YEUNG Sze-chun 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHIU Ka-yin, Andrew 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHIU Chi-keung 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAU Hing-yeung 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHENG Chi-sing 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAI Chi-keong, Joseph 2:30 end of meeting Mr NGAN Chun-lim, MH 2:30 end of meeting Mr LO Wing-kwan, Frankie, MH (Chairman) 2:30 end of meeting Mr FAN Hai-tai (Co-opted Member) 2:30 end of meeting Absent with Apologies Mr HUI Lam-hing (Vice-chairman) (absent with consent) Mr NG Kwan-yuk (Co-opted Member) 1 In Regular Attendance (Government Representatives) Miss NGAI Lai-ying, Angora Assistant District Officer (Eastern)1, Eastern District Office Miss WAH Pui-yee, Vivian Senior Executive Officer (District Council), Eastern District Office Miss HAU Tsun-tsun, Kenix Executive Officer I (District Council)1, (Secretary) Eastern District Office In Attendance by Invitation (Representatives from the Government and Organisations) Miss TANG Wai-yan, Zoe Manager (Hong Kong East) Marketing, Programme and District Activities, Leisure and Cultural Services Department Opening Remarks The Chairman welcomed all Members and Government representatives to the meeting. -

Minutes of the 3 Meeting of the Eastern District Council Date

Minutes of the 3rd Meeting of the Eastern District Council Date : 26 April 2016 (Tuesday) Time : 2:30 pm Venue : Eastern District Council Conference Room Present Time of Arrival Time of Departure (pm) (pm) Mr TING Kong-ho, Eddie 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Chi-chung, Dominic 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Chun-sing, Patrick 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Kwok-hing, BBS, MH 2:30 5:00 Mr KU Kwai-yiu 2:30 end of meeting Mr HO Ngai-kam, Stanley 2:30 end of meeting Ms LI Chun-chau 2:30 end of meeting Mr LEE Chun-keung 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAM Sum-lim 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAM Kei-tung, George 2:30 end of meeting Ms LAM Chui-lin, Alice, MH 2:30 end of meeting Mr SHIU Ka-fai 2:30 end of meeting Mr HUNG Lin-cham 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHUI Chi-kin 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHEUNG Kwok-cheong, Howard 2:30 end of meeting Mr LEUNG Siu-sun, Patrick 2:30 end of meeting Mr LEUNG Kwok-hung, David 2:30 end of meeting Mr HUI Lam-hing 2:30 end of meeting Mr HUI Ching-on 2:32 end of meeting Mr KWOK Wai-keung, Aron 3:20 5:10 Mr MAK Tak-ching 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Kin-pan, MH, JP (Chairman) 2:30 end of meeting Mr WONG Kin-hing 2:30 end of meeting Mr YEUNG Sze-chun 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHIU Ka-yin, Andrew 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHIU Chi-keung (Vice-chairman) 2:30 end of meeting Mr LAU Hing-yeung 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHENG Chi-sing 2:30 end of meeting Mr CHENG Tat-hung 2:47 end of meeting Mr LAI Chi-keong, Joseph 2:30 end of meeting Mr NGAN Chun-lim, MH 2:30 end of meeting Mr LO Wing-kwan, Frankie, MH 2:35 end of meeting Mr KUNG Pak-cheung, MH 2:30 end -

Diasporas and Transnationalism

METROPOLIS WORLD BULLETIN September 2006 Volume 6 Diasporas and Transnationalism Disponible en français à www.metropolis.net Diasporas and Transnationalism HOWARD DUNCAN Executive Head, Metropolis Project and Co-Chair, Metropolis International Steering Committee hose of us who follow international migration are once again paying attention to transnational communities T or, as we have now come to use this term, diasporas. The contexts of the discussions are many, an indication in itself of the new centrality of diasporas for us. These terms immediately connote homeland connections which is the main reason for our interest in them. But, whereas in previous years the academic interest in the immigrant diaspora was on the social and economic relations within the group, we are now seeing a growing interest in relations between diaspora groups and the members of the destination society. From one point of view, the tie to a homeland may be regarded as a counter force to full integration and citizenship in the society of destination. For societies that prefer temporary forms of residence, however, the draw of homeland might instil greater public confidence in a state’s immigration program. But the question has become whether internal diaspora relations affect the integration or degree of attachment that immigrants feel towards their new homes. We hope that this issue of the Metropolis World Bulletin will help us to appreciate the wide scope of transnationalism and the policy implications of this phenomenon. Regardless of one’s particular take on these communities, it is crucial to understand how transnational communities function and what are their actual effects both upon destination societies and upon the homeland. -

Fourth Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Of

Fourth Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China under the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women i CONTENT Fourth Report of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China under the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Paragraph PREAMBLE 1-5 ARTICLE 1: DEFINING DISCRIMINATION Definition of discrimination against women in the Sex 6 Discrimination Ordinance Reservations and declarations to the application of the 7 Convention in the HKSAR ARTICLE 2: OBLIGATIONS OF STATE PARTIES 8 The Basic Law and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights 9 Legislation – The four anti-discrimination ordinances 10 Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) 13 Women’s Commission (WoC) 16 – The organisation, role and function of WoC 18 – Increase of resources for WoC 20 ARTICLE 3: APPROPRIATE MEASURES Gender mainstreaming 21 Studies, research and data collection on women – Collection of sex-disaggregated statistics 24 – Surveys and researches conducted by WoC 26 i Paragraph – Surveys and researches conducted by EOC 27 ARTICLE 4: TEMPORARY SPECIAL MEASURES Reservation entered in respect of this Article 28 ARTICLE 5: STEREOTYPING AND PREJUDICES Review of sexual offences 29 Efforts to eliminate discrimination on the grounds of sexual 30 orientation and gender identity Public education efforts – Promotion of the Convention 32 Control of pornography and sex discriminatory elements in the 33 media – The -

Minutes of the Second Meeting of the Eastern District Council Date: 7

Minutes of the Second Meeting of the Eastern District Council Date: 7 January 2020 (Tuesday) Time: 11:00 am Venue: Eastern District Council Conference Room Present Time of Arrival Time of Departure (am) (pm) Ms CHAU Hui-yan 11:00 end of meeting Mr WONG Chun-sing, Patrick 11:00 end of meeting Mr KU Kwai-yiu 11:00 end of meeting Mr HO Wai-lun 11:00 end of meeting Mr NG Cheuk-ip 11:00 end of meeting Mr LEE Yue-shun 11:00 end of meeting Ms LEE Ching-har, Annie 11:00 end of meeting Ms ISHIGAMI LEE Fung-king, Alice 11:00 end of meeting Mr YUEN Kin-chung, Kenny 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHOW Cheuk-ki 11:00 end of meeting Ms WEI Siu-lik 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHUI Chi-kin 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHEUNG Chun-kit 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHEUNG Kwok-cheong 11:00 end of meeting Mr LEUNG Siu-sun, Patrick 11:00 end of meeting Ms LEUNG Wing-sze 11:00 end of meeting Mr KWOK Chi-chung 11:00 end of meeting Mr KWOK Wai-keung, JP 11:00 2:07 Mr CHAN Ka-yau, Jason 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHAN Wing-tai 11:00 end of meeting Ms CHAN Po-king 11:00 end of meeting Mr MAK Tak-ching 11:00 end of meeting Ms FU Kai-lam, Karrine 11:00 end of meeting Ms TSANG Yan-ying 11:00 end of meeting Mr TSANG Kin-shing, Bull 11:00 end of meeting Ms WONG Yi, Christine 11:00 end of meeting Mr PUI Chi-lap, James 11:00 end of meeting Dr CHIU Ka-yin, Andrew (Vice-chairman) 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHOI Chi-keung, Peter 11:00 end of meeting Mr CHENG Tat-hung 11:00 end of meeting Mr LAI Chi-keong, Joseph (Chairman) 11:00 end of meeting Ms LAI Tsz-yan 11:00 end of meeting Ms TSE Miu-yee 11:00