Implement Liquid Democracy on Ethereum: a Fast Algorithm for Realtime Self-Tally Voting System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Liquid Democracy System for Human-Computer Societies

A Liquid Democracy System for Human-Computer Societies Anton Kolonin, Ben Goertzel, Cassio Pennachin, Deborah Duong, Marco Argentieri, Matt Iklé, Nejc Znidar SingularityNET Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands {anton, ben, cassio}@singularitynet.io Abstract replicated in latest developments of distributed computing system based on Proof-of-Stake (PoS) in blockchain. In the Problem of reliable democratic governance is blockchain systems, including some that are now used to critical for survival of any community, and it will design ecosystems for Artificial Intelligence (AI) be critical for communities powered with Artificial applications, the mostly suggested solution called Delegated Intelligence (AI) systems upon developments of Proof-of-Stake (DPoS), which effectively means that rule on the latter. Apparently, it will be getting more and basis of financial capabilities while it is implemented more critical because of increasing speeds and indirectly, by means of manually controlled voting process scales of electronic communications and to select delegates to conduct the governance of the system. decreasing latencies in system responses. In order The latter be only limited improvement and can nor be to address this need, we present design and implemented in AI communities operating at high speeds implementation of a reputation system supporting not controllable by means of limited human capabilities. “liquid democracy” principle. The system is based on “weighted liquid rank” algorithm employing The described situation leads to the danger that consensus in different sorts of explicit and implicit ratings being any emergent AI community may be quickly took over by exchanged by members of the society as well as AI system hostile to either majority of community of AI implicit assessments of of the members based on systems or humans that are supposed to be served by given measures of their activity in the society. -

Interactive Democracy Blue Sky Ideas Track

Session 29: Blue Sky AAMAS 2018, July 10-15, 2018, Stockholm, Sweden Interactive Democracy Blue Sky Ideas Track Markus Brill TU Berlin Berlin, Germany [email protected] ABSTRACT approached this question by developing an app, DemocracyOS [48], Interactive Democracy is an umbrella term that encompasses a va- that allows users to propose, debate, and vote on issues. Democ- riety of approaches to make collective decision making processes racyOS is only one example of a quickly growing number of ap- more engaging and responsive. A common goal of these approaches proaches that aim to reconcile established democratic processes is to utilize modern information technology—in particular, the with the desire of citizens to participate in political decision mak- 1 Internet—in order to enable more interactive decision making pro- ing. Another example is the software LiquidFeedback [6], which is 2 cesses. An integral part of many interactive democracy proposals developed by the Association for Interactive Democracy. Currently, are online decision platforms that provide much more flexibility these tools are mainly used for decision making within progressive and interaction possibilities than traditional democratic systems. political parties [9, p. 162] or in the context of community engage- This is achieved by embracing the novel paradigm of delegative ment platforms such as WeGovNow [10]. A common goal of these voting, often referred to as liquid democracy, which aims to recon- approaches, often summarized under the umbrella term Interac- 3 cile the idealistic appeal of direct democracy with the practicality tive Democracy (henceforth ID), is to utilize modern information of representative democracy. The successful design of interactive technology—in particular, the Internet—in order to enable more democracy systems presents a multidisciplinary research challenge; interactive decision making processes. -

Democracy on the Precipice Council of Europe Democracy 2011-12 Council of Europe Publishing Debates

Democracy on the Precipice Democracy Democracy is well-established and soundly practiced in most European countries. But despite unprecedented progress, there is growing dissatisfaction with the state of democracy and deepening mistrust of democratic institutions; a situation exacer- Democracy on the Precipice bated by the economic crisis. Are Europe’s democracies really under threat? Has the traditional model of European democracy exhausted its potential? A broad consensus is forming as to the urgent need to examine the origins of the crisis and to explore Council of Europe visions and strategies which could contribute to rebuilding confidence in democracy. Democracy Debates 2011-12 As Europe’s guardian of democracy, human rights and the rule of law, the Council of Europe is committed to exploring the state and practice of European democracy, as Debates of Europe Publishing 2011-12 Council Council of Europe Democracy well as identifying new challenges and anticipating future trends. In order to facilitate Preface by Thorbjørn Jagland this reflection, the Council of Europe held a series of Democracy Debates with the participation of renowned specialists working in a variety of backgrounds and disciplines. This publication presents the eight Democracy Debate lectures. Each presentation Zygmunt Bauman analyses a specific aspect of democracy today, placing the issues not only in their political context but also addressing the historical, technological and communication Ulrich Beck dimensions. The authors make proposals on ways to improve democratic governance Ayşe Kadıoğlu and offer their predictions on how democracy in Europe may evolve. Together, the presentations contribute to improving our understanding of democracy today and to John Keane recognising the ways it could be protected and strengthened. -

The Fluid Mechanics of Liquid Democracy

The Fluid Mechanics of Liquid Democracy Paul Gölz Anson Kahng Simon Mackenzie Ariel D. Procaccia Abstract Liquid democracy is the principle of making collective decisions by letting agents transitively delegate their votes. Despite its significant appeal, it has become apparent that a weakness of liquid democracy is that a small subset of agents may gain massive influence. To address this, we propose to change the current practice by allowing agents to specify multiple delegation options instead of just one. Much like in nature, where — fluid mechanics teaches us — liquid maintains an equal level in connected vessels, so do we seek to control the flow of votes in a way that balances influence as much as possible. Specifically, we analyze the problem of choosing delegations to approximately minimize the maximum number of votes entrusted to any agent, by drawing connections to the literature on confluent flow. We also introduce a random graph model for liquid democracy, and use it to demonstrate the benefits of our approach both theoretically and empirically. 1 Introduction Liquid democracy is a potentially disruptive approach to democratic decision making. As in direct democracy, agents can vote on every issue by themselves. Alternatively, however, agents may delegate their vote, i.e., entrust it to any other agent who then votes on their behalf. Delegations are transitive; for example, if agents 2 and 3 delegate their votes to 1, and agent 4 delegates her vote to 3, then agent 1 would vote with the weight of all four agents, including herself. Just like representative democracy, this system allows for separation of labor, but provides for stronger accountability: Each delegator is connected to her transitive delegate by a path of personal trust relationships, and each delegator on this path can withdraw her delegation at any time if she disagrees with her delegate’s choices. -

Governance in Decentralized Networks

Governance in decentralized networks Risto Karjalainen* May 21, 2020 Abstract. Effective, legitimate and transparent governance is paramount for the long-term viability of decentralized networks. If the aim is to design such a governance model, it is useful to be aware of the history of decision making paradigms and the relevant previous research. Towards such ends, this paper is a survey of different governance models, the thinking behind such models, and new tools and structures which are made possible by decentralized blockchain technology. Governance mechanisms in the wider civil society are reviewed, including structures and processes in private and non-profit governance, open-source development, and self-managed organisations. The alternative ways to aggregate preferences, resolve conflicts, and manage resources in the decentralized space are explored, including the possibility of encoding governance rules as automatically executed computer programs where humans or other entities interact via a protocol. Keywords: Blockchain technology, decentralization, decentralized autonomous organizations, distributed ledger technology, governance, peer-to-peer networks, smart contracts. 1. Introduction This paper is a survey of governance models in decentralized networks, and specifically in networks which make use of blockchain technology. There are good reasons why governance in decentralized networks is a topic of considerable interest at present. Some of these reasons are ideological. We live in an era where detailed information about private individuals is being collected and traded, in many cases without the knowledge or consent of the individuals involved. Decentralized technology is seen as a tool which can help protect people against invasions of privacy. Decentralization can also be viewed as a reaction against the overreach by state and industry. -

Forms of Government (World General Knowledge)

Forms of Government (World General Knowledge) Anarchism A system that advocates self-governed societies based on voluntary institutions. These are often described as stateless societies, although several authors have defined them more specifically as institutions based on non-hierarchical or free associations. Anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary, and/or harmful. Anarchy A society without a publicly enforced government or political authority. Sometimes said to be non-governance; it is a structure which strives for non-hierarchical, voluntary associations among agents. Anarchy is a situation where there is no state. Autocracy Autocracy is a system of government in which supreme power (social and political) is concentrated in the hands of one person or polity, whose decisions are subject to neither external legal restraints nor regularized mechanisms of popular control Aristocracy Rule by the nobility; a system of governance where political power is in the hands of a small class of privileged individuals who claim a higher birth than the rest of society. Anocracy A regime type where power is not vested in public institutions (as in a normal democracy) but spread amongst elite groups who are constantly competing with each other for power. Adhocracy Rule by a government based on relatively disorganised principles and institutions as compared to a bureaucracy, its exact opposite. Absolute monarchy A traditional and historical system where the monarch exercises ultimate governing Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 Forms of Government (World General Knowledge) authority as head of state and head of government. Many nations of Europe during the Middle Ages were absolute monarchies. -

Electronic Democracy the World of Political Science— the Development of the Discipline

Electronic Democracy The World of Political Science— The development of the discipline Book series edited by Michael Stein and John Trent Professors Michael B. Stein and John E. Trent are the co-editors of the book series “The World of Political Science”. The former is visiting professor of Political Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and Emeritus Professor, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The latter is a Fellow in the Center of Governance of the University of Ottawa, in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and a former professor in its Department of Political Science. Norbert Kersting (ed.) Electronic Democracy Barbara Budrich Publishers Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2012 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-86649-546-3. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org © 2012 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0. (CC- BY-SA 4.0) It permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you share under the same license, give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ © 2012 Dieses Werk ist beim Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH erschienen und steht unter der Creative Commons Lizenz Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Diese Lizenz erlaubt die Verbreitung, Speicherung, Vervielfältigung und Bearbeitung bei Verwendung der gleichen CC-BY-SA 4.0-Lizenz und unter Angabe der UrheberInnen, Rechte, Änderungen und verwendeten Lizenz. -

Computational Perspectives on Democracy

Computational Perspectives on Democracy Anson Kahng CMU-CS-21-126 August 2021 Computer Science Department School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Thesis Committee: Ariel Procaccia (Chair) Chinmay Kulkarni Nihar Shah Vincent Conitzer (Duke University) David Pennock (Rutgers University) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Copyright c 2021 Anson Kahng This research was sponsored by the National Science Foundation under grant numbers IIS-1350598, CCF- 1525932, and IIS-1714140, the Department of Defense under grant number W911NF1320045, the Office of Naval Research under grant number N000141712428, and the JP Morgan Research grant. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of any sponsoring institution, the U.S. government or any other entity. Keywords: Computational Social Choice, Theoretical Computer Science, Artificial Intelligence For Grandpa and Harabeoji. iv Abstract Democracy is a natural approach to large-scale decision-making that allows people affected by a potential decision to provide input about the outcome. However, modern implementations of democracy are based on outdated infor- mation technology and must adapt to the changing technological landscape. This thesis explores the relationship between computer science and democracy, which is, crucially, a two-way street—just as principles from computer science can be used to analyze and design democratic paradigms, ideas from democracy can be used to solve hard problems in computer science. Question 1: What can computer science do for democracy? To explore this first question, we examine the theoretical foundations of three democratic paradigms: liquid democracy, participatory budgeting, and multiwinner elections. -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kotsialou, G., & Riley, L. (Accepted/In press). Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation . In International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems 2020: Social Choice and Cooperative Game Theory Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Liquid Democracy: an Algorithmic Perspective

Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 70 (2021) 1223-1252 Submitted 11/2020; published 03/2021 Liquid Democracy: An Algorithmic Perspective Anson Kahng [email protected] Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University Simon Mackenzie [email protected] University of New South Wales Ariel D. Procaccia [email protected] School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University Abstract We study liquid democracy, a collective decision making paradigm that allows voters to transitively delegate their votes, through an algorithmic lens. In our model, there are two alternatives, one correct and one incorrect, and we are interested in the probability that the majority opinion is correct. Our main question is whether there exist delegation mechanisms that are guaranteed to outperform direct voting, in the sense of being always at least as likely, and sometimes more likely, to make a correct decision. Even though we assume that voters can only delegate their votes to better-informed voters, we show that local delegation mechanisms, which only take the local neighborhood of each voter as input (and, arguably, capture the spirit of liquid democracy), cannot provide the foregoing guarantee. By contrast, we design a non-local delegation mechanism that does provably outperform direct voting under mild assumptions about voters. 1. Introduction Liquid democracy is a modern approach to voting in which voters can either vote directly or delegate their vote to other voters. In contrast to the classic proxy voting paradigm (Miller, 1969), the key innovation underlying liquid democracy is that proxies | who were selected by voters to vote on their behalf | may delegate their own vote to a proxy, and, in doing so, further delegate all the votes entrusted to them. -

Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗

Research Paper AAMAS 2020, May 9–13, Auckland, New Zealand Incentivising Participation in Liquid Democracy with Breadth-First Delegation∗ Grammateia Kotsialou Luke Riley Political Economy - King’s College London Informatics - King’s College London, Quant Network London, United Kingdom London, United Kingdom [email protected] luke.riley@{kcl.ac.uk,quant.network} ABSTRACT Party in Argentina and Partido de Internet in Spain have been ex- Liquid democracy allows members of an electorate to either directly perimenting with liquid democracy implementations. Additionally, vote over alternatives, or delegate their voting rights to someone the local governments of the London Southwark borough and the they trust. Most of the liquid democracy literature and implementa- Italian cities Turino and San Dona di Piave are working on integrat- tions allow each voter to nominate only one delegate per election. ing liquid democracy for community engagement processes (Boella However, if that delegate abstains, the voting rights assigned to et al. [2018]). In the technology domain, the online platform Liq- her are left unused. To minimise the number of unused delegations, uidFeedback uses a liquid democracy system where a user selects it has been suggested that each voter should declare a personal a single guru for different topics (Behrens et al. [2014]; Kling etal. ranking over voters she trusts. In this paper, we show that even if [2015]). Another prominent online example is GoogleVotes (Hardt personal rankings over voters are declared, the standard delegation and Lopes [2015]), where each user wishing to delegate can select method of liquid democracy remains problematic. More specifically, a ranking over other voters. -

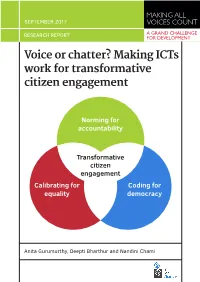

Voice Or Chatter? Making Icts Work for Transformative Citizen Engagement

SEPTEMBER 2017 RESEARCH REPORT Voice or chatter? Making ICTs work for transformative citizen engagement Norming for accountability Transformative citizen engagement Calibrating for Coding for equality democracy Anita Gurumurthy, Deepti Bharthur and Nandini Chami RESEARCH REPORT Voice or chatter? Making ICTs work for transformative citizen engagement Authors Anita Gurumurthy is a founding member and Executive Director of IT for Change, where she leads research on the network society with a focus on governance, democracy and gender justice. She works with policy-makers, practitioners, social movements, activists and the academic community to expand and deepen conversations on the digital, as it rewires social justice, gender relations and citizenship rights. Deepti Bharthur is Research Associate at IT for Change. She contributes to academic, action and policy research in the areas of e-governance and digital citizenship, data economy, platforms and digital exclusions. She has also coordinated and co-developed design-based digital interventions for gender training. Nandini Chami is Senior Research Associate at IT for Change. She works in the areas of digital rights and development, and women’s rights in the information society. She has supported IT for Change’s advocacy efforts around the 2030 development agenda on issues of ‘data for development’, and digital technologies and gender justice. Acknowledgements This report was produced under a research project entitled ‘Voice or chatter? Using a structuration framework towards a theory of ICT-mediated citizen engagement’. The authors of this report coordinated the research, with research assistance from Sanjana Thomas and Amrita Vasudevan, and communications and editorial support from Yogesh Kumar, Swati Mehta, Manu Pandey and Amrita Vasudevan.