Fast Cache Hit by Virtual Cache Fast Cache Hits by Avoiding Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and Power

Chapter 1: Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.6 – 1.7: Performance and power ITSC 3181 Introduction to Computer Architecture https://passlaB.githuB.io/ITSC3181/ Department of Computer Science Yonghong Yan [email protected] https://passlab.github.io/yanyh/ Lectures for Chapter 1 and C Basics Computer Abstractions and Technology • Lecture 01: Chapter 1 – 1.1 – 1.4: Introduction, great ideas, Moore’s law, aBstraction, computer components, and program execution • Lecture 02: C Basics; Memory and Binary Systems • Lecture 03: Number System, Compilation, Assembly, Linking and Program Execution ☛• Lecture 04: Chapter 1 – 1.6 – 1.7: Performance, power and technology trends • Lecture 05: – 1.8 - 1.9: Multiprocessing and Benchmarking 2 § 1.6 Performance 1.6 Defining Performance • Which airplane has the best performance? Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 100 200 300 400 500 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 Passenger Capacity Cruising Range (miles) Boeing 777 Boeing 777 Boeing 747 Boeing 747 BAC/Sud BAC/Sud Concorde Concorde Douglas Douglas DC- DC-8-50 8-50 0 500 1000 1500 0 100000 200000 300000 400000 Cruising Speed (mph) Passengers x mph 3 Response Time and Throughput • Response time çè Latency – How long it takes to do a task • Throughput çè Bandwidth – Total work done per unit time • e.g., tasks/transactions/… per hour • How are response time and throughput affected by – Replacing the processor with a faster version? – Adding more processors? • We’ll focus on response time for now… 4 Relative Performance • Define Performance = 1/Execution Time • “X is n time faster than Y”, i.e. -

Clock Rate Improves Roughly Proportional to Improvement in L • Number of Transistors Improves Proportional to L2 (Or Faster)

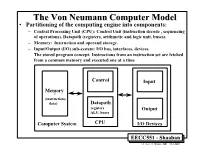

TheThe VonVon NeumannNeumann ComputerComputer ModelModel • Partitioning of the computing engine into components: – Central Processing Unit (CPU): Control Unit (instruction decode , sequencing of operations), Datapath (registers, arithmetic and logic unit, buses). – Memory: Instruction and operand storage. – Input/Output (I/O) sub-system: I/O bus, interfaces, devices. – The stored program concept: Instructions from an instruction set are fetched from a common memory and executed one at a time Control Input Memory - (instructions, data) Datapath registers Output ALU, buses Computer System CPU I/O Devices EECC551 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 Generic CPU Machine Instruction Execution Steps Instruction Obtain instruction from program storage Fetch Instruction Determine required actions and instruction size Decode Operand Locate and obtain operand data Fetch Execute Compute result value or status Result Deposit results in storage for later use Store Next Determine successor or next instruction Instruction EECC551 - Shaaban #2 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 HardwareHardware ComponentsComponents ofof AnyAny ComputerComputer Five classic components of all computers: 1. Control Unit; 2. Datapath; 3. Memory; 4. Input; 5. Output } Processor Computer Keyboard, Mouse, etc. Processor Memory Devices (active) (passive) Control Input (where Unit programs, data Disk Datapath live when Output running) Display, Printer, etc. EECC551 - Shaaban #3 Lec # 1 Winter 2001 12-3-2001 CPUCPU OrganizationOrganization • Datapath Design: – Capabilities & performance characteristics of principal Functional Units (FUs): • (e.g., Registers, ALU, Shifters, Logic Units, ...) – Ways in which these components are interconnected (buses connections, multiplexors, etc.). – How information flows between components. • Control Unit Design: – Logic and means by which such information flow is controlled. – Control and coordination of FUs operation to realize the targeted Instruction Set Architecture to be implemented (can either be implemented using a finite state machine or a microprogram). -

Atmega165p Datasheet

Features • High Performance, Low Power Atmel® AVR® 8-Bit Microcontroller • Advanced RISC Architecture – 130 Powerful Instructions – Most Single Clock Cycle Execution – 32 × 8 General Purpose Working Registers – Fully Static Operation – Up to 16 MIPS Throughput at 16 MHz – On-Chip 2-cycle Multiplier • High Endurance Non-volatile Memory segments – 16 Kbytes of In-System Self-programmable Flash program memory – 512 Bytes EEPROM – 1 Kbytes Internal SRAM 8-bit – Write/Erase cyles: 10,000 Flash/100,000 EEPROM(1)(3) – Data retention: 20 years at 85°C/100 years at 25°C(2)(3) Microcontroller – Optional Boot Code Section with Independent Lock Bits In-System Programming by On-chip Boot Program with 16K Bytes True Read-While-Write Operation – Programming Lock for Software Security In-System • JTAG (IEEE std. 1149.1 compliant) Interface – Boundary-scan Capabilities According to the JTAG Standard Programmable – Extensive On-chip Debug Support – Programming of Flash, EEPROM, Fuses, and Lock Bits through the JTAG Interface Flash • Peripheral Features – Two 8-bit Timer/Counters with Separate Prescaler and Compare Mode – One 16-bit Timer/Counter with Separate Prescaler, Compare Mode, and Capture Mode – Real Time Counter with Separate Oscillator –Four PWM Channels ATmega165P – 8-channel, 10-bit ADC – Programmable Serial USART ATmega165PV – Master/Slave SPI Serial Interface – Universal Serial Interface with Start Condition Detector – Programmable Watchdog Timer with Separate On-chip Oscillator – On-chip Analog Comparator Preliminary – Interrupt and Wake-up -

Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D

ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Computer Architecture and Design Fall 2013 Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D. Agrawal & Victor P. Nelson epartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849 ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 1 What is Performance? Response time: the time between the start and completion of a task. Throughput: the total amount of work done in a given time. Some performance measures: MIPS (million instructions per second). MFLOPS (million floating point operations per second), also GFLOPS, TFLOPS (1012), etc. SPEC (System Performance Evaluation Corporation) benchmarks. LINPACK benchmarks, floating point computing, used for supercomputers. Synthetic benchmarks. ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 2 Small and Large Numbers Small Large 10-3 milli m 103 kilo k 10-6 micro μ 106 mega M 10-9 nano n 109 giga G 10-12 pico p 1012 tera T 10-15 femto f 1015 peta P 10-18 atto 1018 exa 10-21 zepto 1021 zetta 10-24 yocto 1024 yotta ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 3 Computer Memory Size Number bits bytes 210 1,024 K Kb KB 220 1,048,576 M Mb MB 230 1,073,741,824 G Gb GB 240 1,099,511,627,776 T Tb TB ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 4 Units for Measuring Performance Time in seconds (s), microseconds (μs), nanoseconds (ns), or picoseconds (ps). Clock cycle Period of the hardware clock Example: one clock cycle means 1 nanosecond for a 1GHz clock frequency (or 1GHz clock rate) CPU time = (CPU clock cycles)/(clock rate) Cycles per instruction (CPI): average number of clock cycles used to execute a computer instruction. -

Chap01: Computer Abstractions and Technology

CHAPTER 1 Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Eight Great Ideas in Computer Architecture 11 1.3 Below Your Program 13 1.4 Under the Covers 16 1.5 Technologies for Building Processors and Memory 24 1.6 Performance 28 1.7 The Power Wall 40 1.8 The Sea Change: The Switch from Uniprocessors to Multiprocessors 43 1.9 Real Stuff: Benchmarking the Intel Core i7 46 1.10 Fallacies and Pitfalls 49 1.11 Concluding Remarks 52 1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 54 1.13 Exercises 54 CMPS290 Class Notes (Chap01) Page 1 / 24 by Kuo-pao Yang 1.1 Introduction 3 Modern computer technology requires professionals of every computing specialty to understand both hardware and software. Classes of Computing Applications and Their Characteristics Personal computers o A computer designed for use by an individual, usually incorporating a graphics display, a keyboard, and a mouse. o Personal computers emphasize delivery of good performance to single users at low cost and usually execute third-party software. o This class of computing drove the evolution of many computing technologies, which is only about 35 years old! Server computers o A computer used for running larger programs for multiple users, often simultaneously, and typically accessed only via a network. o Servers are built from the same basic technology as desktop computers, but provide for greater computing, storage, and input/output capacity. Supercomputers o A class of computers with the highest performance and cost o Supercomputers consist of tens of thousands of processors and many terabytes of memory, and cost tens to hundreds of millions of dollars. -

RAMP: Research Accelerator for Multiple Processors

Technical Report UCB//CSD-05-1412, September 2005 RAMP: Research Accelerator for Multiple Processors - A Community Vision for a Shared Experimental Parallel HW/SW Platform Arvind (MIT), Krste Asanovic´ (MIT), Derek Chiou (UT Austin), James C. Hoe (CMU), Christoforos Kozyrakis (Stanford), Shih-Lien Lu (Intel), Mark Oskin (U Washington), David Patterson (UC Berkeley), Jan Rabaey (UC Berkeley), and John Wawrzynek (UC Berkeley) Project Summary Desktop processor architectures have crossed a critical threshold. Manufactures have given up attempting to extract ever more performance from a single core and instead have turned to multi-core designs. While straightforward approaches to the architecture of multi-core processors are sufficient for small designs (2–4 cores), little is really known how to build, program, or manage systems of 64 to 1024 processors. Unfortunately, the computer architecture community lacks the basic infrastructure tools required to carry out this research. While simulation has been adequate for single-processor research, significant use of simplified modeling and statistical sampling is required to work in the 2–16 processing core space. Invention is required for architecture research at the level of 64–1024 cores. Fortunately, Moore’s law has not only enabled these dense multi-core chips, it has also enabled extremely dense FPGAs. Today, for a few hundred dollars, undergraduates can work with an FPGA prototype board with almost as many gates as a Pentium. Given the right support, the research community can capitalize on this opportunity too. Today, one to two dozen cores can be programmed into a single FPGA. With multiple FPGAs on a board and multiple boards in a system, large complex architectures can be explored. -

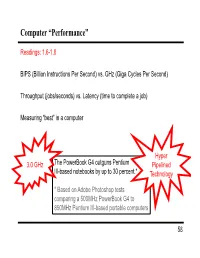

Computer “Performance”

Computer “Performance” Readings: 1.6-1.8 BIPS (Billion Instructions Per Second) vs. GHz (Giga Cycles Per Second) Throughput (jobs/seconds) vs. Latency (time to complete a job) Measuring “best” in a computer Hyper 3.0 GHz The PowerBook G4 outguns Pentium Pipelined III-based notebooks by up to 30 percent.* Technology * Based on Adobe Photoshop tests comparing a 500MHz PowerBook G4 to 850MHz Pentium III-based portable computers 58 Performance Example: Homebuilders Builder Time per Houses Per House Dollars Per House Month Options House Self-build 24 months 1/24 Infinite $200,000 Contractor 3 months 1 100 $400,000 Prefab 6 months 1,000 1 $250,000 Which is the “best” home builder? Homeowner on a budget? Rebuilding Haiti? Moving to wilds of Alaska? Which is the “speediest” builder? Latency: how fast is one house built? Throughput: how long will it take to build a large number of houses? 59 Computer Performance Primary goal: execution time (time from program start to program completion) 1 Performance ExecutionTime To compare machines, we say “X is n times faster than Y” Performance ExecutionTime n x y Performancey ExecutionTimex Example: Machine Orange and Grape run a program Orange takes 5 seconds, Grape takes 10 seconds Orange is _____ times faster than Grape 60 Execution Time Elapsed Time counts everything (disk and memory accesses, I/O , etc.) a useful number, but often not good for comparison purposes CPU time doesn't count I/O or time spent running other programs can be broken up into system time, and user time Example: Unix “time” command linux15.ee.washington.edu> time javac CircuitViewer.java 3.370u 0.570s 0:12.44 31.6% Our focus: user CPU time time spent executing the lines of code that are "in" our program 61 CPU Time CPU execution time CPU clock cycles =*Clock period for a program for a program CPU execution time CPU clock cycles 1 =* for a program for a program Clock rate Application example: A program takes 10 seconds on computer Orange, with a 400MHz clock. -

Intel® Itanium® Architecture Software Developer's Manual

Intel® Itanium® Architecture Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2: System Architecture Revision 2.1 October 2002 Document Number: 245318-004 THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH NO WARRANTIES WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING ANY WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR ANY PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR ANY WARRANTY OTHERWISE ARISING OUT OF ANY PROPOSAL, SPECIFICATION OR SAMPLE. INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED IN CONNECTION WITH INTEL® PRODUCTS. NO LICENSE, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, BY ESTOPPEL OR OTHERWISE, TO ANY INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS IS GRANTED BY THIS DOCUMENT. EXCEPT AS PROVIDED IN INTEL'S TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE FOR SUCH PRODUCTS, INTEL ASSUMES NO LIABILITY WHATSOEVER, AND INTEL DISCLAIMS ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY, RELATING TO SALE AND/OR USE OF INTEL PRODUCTS INCLUDING LIABILITY OR WARRANTIES RELATING TO FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, MERCHANTABILITY, OR INFRINGEMENT OF ANY PATENT, COPYRIGHT OR OTHER INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT. INTEL PRODUCTS ARE NOT INTENDED FOR USE IN MEDICAL, LIFE SAVING, OR LIFE SUSTAINING APPLICATIONS. Intel may make changes to specifications and product descriptions at any time, without notice. Designers must not rely on the absence or characteristics of any features or instructions marked "reserved" or "undefined." Intel reserves these for future definition and shall have no responsibility whatsoever for conflicts or incompatibilities arising from future changes to them. Intel processors based on the Itanium architecture may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Contact your local Intel sales office or your distributor to obtain the latest specifications and before placing your product order. -

The Role of Performance Relating the Metrics CPU Execution Time for a Program = CPU Clock Cycles for a Program * Ming-Hwa Wang, Ph.D

The Role of Performance Relating the Metrics CPU execution time for a program = CPU clock cycles for a program * Ming-Hwa Wang, Ph.D. clock cycle time = CPU clock cycles for a program / clock rate, measured COEN 210 Computer Architecture by running the program Department of Computer Engineering CPU clock cycles = instructions for a program * average CPI or clock Santa Clara University cycles per instruction measuring the instruction count (depends on the architecture but not on the Introduction exact implementation) by using hardware counters or by using software hardware performance is often key to the effectiveness of an entire system tools (that profile the execution or by using a simulator of the architecture) of hardware and software CPI = CPU clock cycles / instruction count, provides one way of comparing accurately measuring and comparing different machines is critical to two different implementations of the same instruction set architecture, CPI purchasers, and therefore to designers varies by applications as well as among implementations with the same for different types of applications, different performance metrics may be instruction set appropriate and different aspects of a computer system may be the most CPU time = instruction count * CPI * clock cycle time = instruction count * significant in determining overall performance CPI / clock rate an individual computer user is interested in reducing response/execution CPU execution time = (instructions / program) * (clock cycles / instruction) * time (the time between the start -

Chapter 4 Accessing and Understanding Performance

ChapterChapter 4 4 AccessingAccessing and and Understanding Understanding PerformancePerformance 1 Performance Why do we care about performance evaluation? –Purchasing perspective given a collection of machines, which has the –best performance ? –least cost ? –best performance / cost ? –Design perspective faced with design options, which has the –best performance improvement ? –least cost ? –best performance / cost ? How to measure, report, and summarize performance? –Performance metric –Benchmark 2 Which of these airplanes has the best performance? What metric defines performance? –Capacity, cruising range, or speed? Speed –Taking one passenger from one point to another in the least time –Transporting 450 passengers from one point to another 3 Two Notions of “Performance” Response Time (latency) –How long does it take for my job to run? –How long does it take to execute a job? –How long must I wait for the database query? Throughput –How many jobs can the machine run at once? –What is the average execution rate? –How much work is getting done? If we upgrade a machine with a new processor what do we increase? If we add a new machine to the lab what do we increase? 4 Execution Time Elapsed Time –counts everything (disk and memory accesses, I/O , etc.) –a useful number, but often not good for comparison purposes CPU time –doesn't count I/O or time spent running other programs –can be broken up into system time, and user time Our focus: user CPU time –time spent executing the lines of code that are "in" our program 5 Definitions Performance is in units of things-per-second –bigger is better If we are primarily concerned with response time " X is n times faster than Y" means 6 Which one is faster? Concorde or Boeing 747 Response Time of Concorde vs. -

TMS320F28035-EP Piccolo™ Microcontroller

Product Order Technical Tools & Support & Folder Now Documents Software Community TMS320F28035-EP SPRSP25A –JUNE 2018–REVISED JULY 2018 TMS320F28035-EP Piccolo™ Microcontroller 1 Device Overview 1.1 Features 1 • High-Efficiency 32-Bit CPU (TMS320C28x) • Code-Security Module – 60 MHz (16.67-ns Cycle Time) • 128-Bit Security Key and Lock – 16 × 16 and 32 × 32 MAC Operations – Protects Secure Memory Blocks – 16 × 16 Dual MAC – Prevents Firmware Reverse Engineering – Harvard Bus Architecture • Serial Port Peripherals – Atomic Operations – One Serial Communications Interface (SCI) – Fast Interrupt Response and Processing Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter – Unified Memory Programming Model (UART) Module – Code-Efficient (in C/C++ and Assembly) – Two Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) Modules • Programmable Control Law Accelerator (CLA) – One Inter-Integrated-Circuit (I2C) Module – 32-Bit Floating-Point Math Accelerator – One Local Interconnect Network (LIN) Module – Executes Code Independently of the Main CPU – One Enhanced Controller Area Network (eCAN) Module • Endianness: Little Endian • Enhanced Control Peripherals • JTAG Boundary Scan Support – ePWM – IEEE Standard 1149.1-1990 Standard Test Access Port and Boundary Scan Architecture – High-Resolution PWM (HRPWM) • Low Cost for Both Device and System: – Enhanced Capture (eCAP) Module – Single 3.3-V Supply – High-Resolution Input Capture (HRCAP) Module – No Power Sequencing Requirement – Enhanced Quadrature Encoder Pulse (eQEP) Module – Integrated Power-On Reset and Brown-Out Reset -

Introduction to Microprocessors

Introduction to Microprocessors Yuri Baida [email protected] [email protected] October 2, 2010 MDSP Project | Intel Lab Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology Agenda • Background and History – What is a microprocessor? – What is the history of the development of the microprocessor? – How does transistor scaling affect processor design? • PC Components – What are the major PC components and their functions? – What is memory hierarchy and how has it changed? • Processor Architecture – What are processor architecture and microarchitecture? – How does microarchitecture affect performance? – How is performance measured? MDSP Project | Intel Lab Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology 2 Background and History MDSP Project | Intel Lab Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology 3 What is a Microprocessor? • Microprocessor is a computer Central Processing Unit (CPU) on a single chip. • It contains millions of transistors connected by wires Core i7 die Core i7 in package Picture: Intel Picture: Ebbesen MDSP Project | Intel Lab Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology 4 Electrical Numerical Integrator and Calculator • Designed for the U.S. Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory • Built out of – 17,468 vacuum tubes – 7,200 crystal diodes – 1,500 relays – 70,000 resistors – 10,000 capacitors • Consumed 150 kW of power • Took up 72 m2 • Weighted 27 tons • Suffered a failure on average every 6 hours MDSP Project | Intel Lab Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology 5 Electrical Numerical Integrator and Calculator Glen Beck and Betty