New York State Transportation Fuels Infrastructure Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cenovus Reports Second-Quarter 2020 Results Company Captures Value by Leveraging Flexibility of Its Operations Calgary, Alberta (July 23, 2020) – Cenovus Energy Inc

Cenovus reports second-quarter 2020 results Company captures value by leveraging flexibility of its operations Calgary, Alberta (July 23, 2020) – Cenovus Energy Inc. (TSX: CVE) (NYSE: CVE) remained focused on financial resilience in the second quarter of 2020 and used the flexibility of its assets and marketing strategy to adapt quickly to the changing external environment. This positioned the company to weather the sharp decline in benchmark crude oil prices in April by reducing volumes at its oil sands operations and storing the mobilized oil in its reservoirs for production in an improved price environment. While Cenovus’s financial results were impacted by the weak prices early in the quarter, the company captured value by quickly ramping up production when Western Canadian Select (WCS) prices increased almost tenfold from April to an average of C$46.03 per barrel (bbl) in June. As a result of this decision, Cenovus reached record volumes at its Christina Lake oil sands project in June and achieved free funds flow for the month of more than $290 million. “We view the second quarter as a period of transition, with April as the low point of the downturn and the first signs of recovery taking hold in May and June,” said Alex Pourbaix, Cenovus President & Chief Executive Officer. “That said, we expect the commodity price environment to remain volatile for some time. We believe the flexibility of our assets and our low cost structure position us to withstand a continued period of low prices if necessary. And we’re ready to play a significant -

Detailed List of 2018 Investments

FOR THE YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 & DECEMBER 31, 2017 PREPARED BY The Finance Department of the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund OAK BROOK OFFICE 2211 York Road, Suite 500, Oak Brook, IL 60523-2337 SPRINGFIELD REGIONAL COUNSELING CENTER 3000 Professional Drive, Suite 101, Springfield, IL 62703-5934 CONTACT IMRF 1-800-ASK-IMRF (275-4673) www.imrf.org Brian Collins Executive Director At IMRF we REAACH for our goals. These values guide IMRF to REAACH our mission, vision, and goals. They define how we work and shape the expectations we have for our organization. Through our commitment to these values, our members, employers, and stakeholders across Illinois and beyond can feel confident in IMRF as a world-class pension provider. FOR THE YEARS ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2018 & DECEMBER 31, 2017 PREPARED BY The Finance Department of the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund IMRF MISSION OAK BROOK OFFICE STATEMENT 2211 York Road, Suite 500, Oak Brook, IL 60523-2337 To efficiently and impartially develop, implement, and administer programs SPRINGFIELD REGIONAL COUNSELING CENTER that provide income protection to 3000 Professional Drive, Suite 101, members and their beneficiaries on Springfield, IL 62703-5934 behalf of participating employers, in a prudent manner. CONTACT IMRF 1-800-ASK-IMRF (275-4673) www.imrf.org Brian Collins Executive Director At IMRF FIXED INCOME U.S. Securities Corporate Bonds Interest Market Asset Description Maturity Date Par Value Cost Value Rate Value 1 Mkt Plaza Tr 3.85% 02/10/2032 $ 605,000 $ 623,147 $ 604,812 1st Horizon -

BPC-2012-PRS-20-2012-V1 Workshops Contractstrategy.Pdf

Contract Strategy Critical to Your Project’s Success Agenda Introductions Safety Moment Sub-committee Scope Workshop Scope Exercise # 1 Business Need Exercise #2 Wrap-up Our Team Bill Somerville, Nexen Randy Bignell, Bantrel Jason Bobier, Nexen John Taylor, Corporate-Commercial Lawyer Nicola Haig, Athabasca Oil Paul Bourque, Clearstream Safety Moment Share the Road! Committee Scope Develop a Best Practice for the Development and Selection of Contracting Strategies for Capital Projects Encourage Owners and Contractors to Utilize the Recommended Best Practice Our Objective To improve capital project execution through the use of a (Contracting Strategy) best practice that will facilitate the selection of the appropriate contract, which is designed to increase the probability of: achieving project goals; and successfully completing the project Workshop Scope Communicate our objectives, scope and work done to date; and Obtain your feedback and support Exercise #1 Industry Checkup Have you ever been on a project that went completely sideways? Was it the other guy’s fault? Were you slightly, slightly, slightly to blame? Could the project have been planned, set up, and contracted in such a way to improve the project’s outcomes? Business Need Research has shown that if undertaken at the beginning of a project: •Effective risk assessment; and subsequent •Contract Strategy including: •Assignment of Contract Scopes; •Interfaces Split; and •Contract Terms Will have a better chance of being •Fit for purpose •Flexible •Able to -

New Book on Irving Oil Explores Business

New book on Irving Oil explores business Miramichi Leader (Print Edition)·Nathalie Sturgeon CA|September 25, 2020·08:00am Section: B·Page: B6 SAINT JOHN • New Brunswick scholar and author Donald J. Savoie has published a new book exploring the origins of the Irving Oil empire. Savoie, who is the Canada Research Chair in Public Administration and Governance at the Université de Moncton, has released Thanks for the Business: Arthur L. Irving, K.C. Irving and the Story of Irving Oil. It’s look at entrepreneurship through the story of this prominent Maritime business family. “New Brunswickers, and Maritimers more generally, should applaud business success,” said Savoie, who describes himself as a friend of Arthur Irving. “We haven’t had a strong record of applauding business success. I think K.C. Irving, Arthur Irving, and Irving Oil speak to business success.” Irving Oil is the David in a David and Goliath story of major oil refineries in the world, Savoie noted, adding it provides a valuable economic contribution to the province as a whole, having laid the in-roads within New Brunswick into a multi-country oil business. He wanted his book to serve as a reminder of that. In a statement, Candice MacLean, a spokeswoman for Irving Oil, said company employees are proud to read the story of K.C. Irving, the company’s founder, and Arthur Irving, the company’s current chairman. “(Arthur’s) passion and love for the business inspires all of us every day,” MacLean said. “Mr Savoie’s Thanks for the Business captures the story of the Irving Oil that we are proud to be a part of.” In his new book, Savoie, who has won the Donner Prize for public policy writing, details Irving Oil’s “success born in Bouctouche and grown from Saint John, New Brunswick.” The company now operates Canada’s largest refinery, along with more than 900 gas stations spanning eastern Canada and New England, according to Savoie. -

An Effects-Based Assessment of the Health of Fish in a Small Estuarine Stream Receiving Effluent from an Oil Refinery

An effects-based assessment of the health of fish in a small estuarine stream receiving effluent from an oil refinery by Geneviève Vallières B.Sc. Biology, Université de Sherbrooke, 1998 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science In the Graduate Academic Unit of Biology Supervisors: Kelly Munkittrick, Ph.D. Department of Biology Deborah MacLatchy, PhD. Department of Biology Examining Board: Kenneth Sollows, Ph.D., Department of Engineering, Chair Simon Courtenay, Ph. D. Department of Biology External Examiner: Kenneth Sollows, Ph.D., Department of Engineering This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate studies. THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2005 © Geneviève Vallières, 2005 ABSTRACT A large oil refinery discharges its effluent into Little River, a small estuarine stream entering Saint John Harbour. An effects-based approach was used to assess the potential effects of the oil refinery effluent on fish and fish habitat. The study included a fish community survey, a sentinel species survey, a fish caging experiment, and a water quality survey. The study showed that the fish community and the sentinel species, the mummichog (Fundulus heteroclitus), were impacted in the stream receiving the oil refinery effluent. Lower abundance and species richness were found downstream of the effluent discharge whereas increased liversomatic index and MFO (females only) were measured in fish collected in Little River. Water quality surveys demonstrated that the receiving environment is subjected to extended periods of low dissolved oxygen levels downstream of the effluent discharge. The anoxic periods correlated with the discharge of ballast water through the waste treatment system. -

OR18-9-000 White Cliffs Pipeline, L.L.C

173 FERC ¶ 61,155 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION Before Commissioners: James P. Danly, Chairman; Neil Chatterjee and Richard Glick. White Cliffs Pipeline, L.L.C. Docket No. OR18-9-000 OPINION NO. 573 ORDER ON INITIAL DECISION (Issued November 19, 2020) This order addresses briefs on and opposing exceptions to an Initial Decision issued on September 12, 2019 concerning the application for market-based rate authority of White Cliffs Pipeline, L.L.C. (White Cliffs).1 The Initial Decision found that White Cliffs lacks market power in the origin market and recommended that the Commission grant White Cliffs’ application. As discussed below, although we modify the Initial Decision’s findings regarding the product market, we affirm the Initial Decision’s finding that White Cliffs lacks market power in the applicable market and grant White Cliffs’ application for market- based rate authority. I. Background White Cliffs owns and operates a 527-mile common carrier crude oil pipeline system that consists of two parallel 12.75-inch pipelines capable of transporting crude oil from Platteville, Colorado, and Healy, Kansas, to Cushing, Oklahoma (White Cliffs Pipeline).2 White Cliffs is a joint venture majority-owned by Rose Rock Midstream, L.P., a wholly-owned subsidiary of SemGroup Corporation.3 At the time White Cliffs filed for market-based rate authority, White Cliffs Pipeline had a capacity of 185,000 barrels per day. During the pendency of this case, White Cliffs converted one of its pipelines from transporting crude oil to transporting natural gas liquids, which reduced 1 White Cliffs Pipeline, L.L.C., 168 FERC ¶ 63,033 (2019) (Initial Decision). -

The Dark Side of the Attack on Colonial Pipeline

“Public GitHub is 54 often a blind spot in the security team’s perimeter” Jérémy Thomas Co-founder and CEO GitGuardian Volume 5 | Issue 06 | June 2021 Traceable enables security to manage their application and API risks given the continuous pace of change and modern threats to applications. Know your application DNA Download the practical guide to API Security Learn how to secure your API's. This practical guide shares best practices and insights into API security. Scan or visit Traceable.ai/CISOMag EDITOR’S NOTE DIGITAL FORENSICS EDUCATION MUST KEEP UP WITH EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES “There is nothing like first-hand evidence.” Brian Pereira - Sherlock Holmes Volume 5 | Issue 06 Editor-in-Chief June 2021 f the brilliant detective Sherlock Holmes and his dependable and trustworthy assistant Dr. Watson were alive and practicing today, they would have to contend with crime in the digital world. They would be up against cybercriminals President & CEO Iworking across borders who use sophisticated obfuscation and stealth techniques. That would make their endeavor to Jay Bavisi collect artefacts and first-hand evidence so much more difficult! As personal computers became popular in the 1980s, criminals started using PCs for crime. Records of their nefarious Editorial Management activities were stored on hard disks and floppy disks. Tech-savvy criminals used computers to perform forgery, money Editor-in-Chief Senior Vice President laundering, or data theft. Computer Forensics Science emerged as a practice to investigate and extract evidence from Brian Pereira* Karan Henrik personal computers and associated media like floppy disk, hard disk, and CD-ROM. This digital evidence could be used [email protected] [email protected] in court to support cases. -

The Energy Sector an Investment in the People and Communities of Atlantic Canada

The Energy Sector An Investment in the People and Communities of Atlantic Canada January 2008 The Energy Sector An Investment in the People North America needs energy and Canada, and Communities of Atlantic the United States and Mexico want to find it closer to home. These twin needs of Canada increasing demand and increased security have created a unique opportunity for On the doorstep of a growing Atlantic Canada that could drive job market 2 creation, community development and Distance between Atlantic Canada’s investment in the region well into the next major centres and the ports decade and beyond. of Boston and New York (chart) 3 Oil, natural gas and electricity; Atlantic Atlantic Canada’s energy mix 3 Canada develops and delivers all three major forms of energy for its own communities Projects and players in Atlantic and for export around the continent to be Canada’s energy sector 5 used as heat, fuel and power in homes and New Brunswick 5 businesses. Over the last few decades, the Nova Scotia 6 Atlantic Canadian energy industry has laid Newfoundland and Labrador 8 the foundation for what has become one of Prince Edward Island 9 the most significant sectors in the regional economy, and, increasingly, one of the most Exporting energy resources; diverse with its mix of traditional thermal importing human resources 10 and hydroelectric generation with newer technology such as nuclear, wind, bioenergy and tidal. Matching people and skill sets 12 Occupations that will be required by the Atlantic Canadian On the doorstep of a growing energy sector over the next decade market (chart) 12 Energy accounts for just over half of all exports from Atlantic Canada and it now Engaging in all aspects of stands poised to significantly increase its community life 13 reach. -

Matching Gift Programs * Please Note, This List Is Not All Inclusive

Companies With Matching Gift Programs * Please note, this list is not all inclusive. If your employer is not listed, please check with human resources to see if your company matches and the guidelines for matches. A AlliedSignal Inc. Archer Daniels Midland 3Com Corporation Allstate Foundation, Allstate Giving ARCO Chemical Co. 3M Company Altera Corp. Contributions Program Ares Advanced Technology AAA Altria Employee Involvement Ares Management LLC Abacus Capital Investments Altria Group Argonaut Group Inc. Abbot Laboratories AMB Group Aristokraft Inc. Accenture Foundation, Inc. Ambac Arkansas Best Corporation Access Group, Inc. AMD Corporate Giving Arkwright Mutual Insurance Co. ACE INA Foundation American Express Co. Armco Inc. Acsiom Corp. American Express Foundation Armstrong Foundation Adams Harkness and Hill Inc. American Fidelity Corp. Arrow Electronics Adaptec Foundation American General Corp. Arthur J. Gallagher ADC Foundation American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Ashland Oil Foundation, Inc. ADC Telecommunications American Inter Group Aspect Global Giving Program Adobe Systems Inc. American International Group, Inc. Aspect Telecommunications Associates ADP Foundation American National Bank and Trust Co. Corp. of North America A & E Television Networks of Chicago Assurant Health AEGON TRANSAMERICA American Standard Foundation Astra Merck Inc. AEP American Stock Exchange AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical LP AES Corporation Ameriprise Financial Atapco A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Ameritech Corp. ATK Foundation Aetna Foundation, Inc. Amgen Center Atlantic Data Services Inc. AG Communications Systems Amgen Foundation Atochem North America Foundation Agilent Technologies Amgen Inc. ATOFINA Chemicals, Inc. Aid Association for Lutherans AMN Healthcare Services, Inc. ATO FINA Pharmaceutical Foundation AIG Matching Grants Program Corporate Giving Program AT&T Aileen S. Andrew Foundation AmSouth BanCorp. -

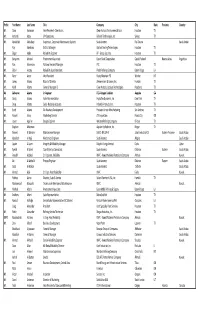

Ms Catherine Sr PCS Fertilizer GA I Al Aithan Dh Ran H I Prefix First Name

Prefix First Name Last Name Title Company City State Province Country Mr. Dana Aaronson Vice President ‐ Operations Clean Harbors Environmental Svcs Houston TX Mr. Armand Abay VP Operations Refined Technologies, Inc. Spring TX Mr. Abdulelah Abdulbaqi Supervisor, Corporate Maintenance Systems Saudi Aramco Ras Tanura Saudi Arabia Roy Abeldano District Manager Garlock Sealing Technologies Houston TX Mr. Edgar Ablan Reliability Engineer BP ‐ Group Security Houston TX Mr. Benjamin Achaval Procurement Associate Exxon Mobil Corporation Capital Federal Buenos Aires Argentina Mr. Ron Ackerman National Account Manager PSC Houston TX Mr. Eddie Acosta Reliability Superintendent Placid Refining Company Baton Rouge LA Mr. Terry Acree Vice President Rocky Mountain PSI Worden MT Mr. James Adams Board of Director Zimmermann & Jansen, Inc. Humble TX Mr. Keith Adams General Manager IS Clean Harbors Catalyst Technologies Pasadena TX Ms Catherine AdamsAdams Sr EnEngineergineer PCS NitroNitrogengen Fertilizer AuAugustagusta GA Ms. Cindy Adams Sales Representative HydroTex Dynamics, Inc. Deer Park TX Doug Adams Sales‐ National Accounts InduMar Products, Inc. Houston TX Mr. Scott Adams Dir. Business Development Precision Screen Manufactoring San Anotnio TX Mr. Russell Aday Marketing Director CFS Inspection Ponca City OK Mr. Javier Aguirre Design Engineer Western Refining Company El Paso TX Stephen Akkerman Aquilex Hydrochem, Inc Borger TX Mr. Ahmed Al Bahrani Maintenance Manager SABIC‐ IBN ZAHR Jubail Industrial City Eastern Province Saudi Arabia Mr. Abdullah Al Hajji Mechanical Engineer Saudi Aramco Abqaiq Saudi Arabia Mr. Jassim Al Jasmi Integrity & Reliability Manager Dolphin Energy Limited Doha Qatar Mr. Ayedh Al Saleh Coord Elec Sys Consultant Saudi Aramco Dhahran Eastern Saudi Arabia Mr. Reyadh Alabdali Sr. Engineer, Reliablity KNPC ‐ Kuwait National Petroleum Company Ahmadi Kuwait Ali Al‐Abdul'al Process Engineer Saudi Aramco Dhahran Eastern Saudi Arabia MrMr. -

ALUMNI NEWS Winter 2004

FORGING OUR FUTURES — CAMPAIGN UNB PAGE 6 UNB Vol. 12 No. 2 ALUMNI NEWS Winter 2004 MAKING A SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE OLD ARTS BUILDING UNB UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK TURNS 175 WWW.UNB.CA/UNBDIFFERENCE Be part of it! Welcome to the University of New Brunswick Alumni & Friends Travel Club. We are pleased to offer you this opportunity to preview our exciting line-up of travel programs, both domestic and abroad. Our goal is to offer enriching travel experiences along with the opportunity to connect with UNB alumni, their families and friends. Embark on an unforgettable journey! EXPLORER Don’t just dream of the exciting places you’d like to Discover South America visit . do it! See the world with us as we fly the April 15 — April 29, 2004 UNB flag around the globe. Embark on an unforgettable journey and discover the captivating BE PART OF IT! flavor of South America. Your adventure can be extended with optional 3-night pre-Machu Picchu and/or post-Amazon excursions. Highlights: Santiago • Folklore Show • Puerto Varas • The Lake Highlights: 4 rounds of golf with cart: The Lynx at Kingswood; District • Crossing of the Andes • Peulla • Bariloche • Buenos Aires • Royal Oaks; Crowbush; Mill River • Welcome reception • Deluxe Tango Show • Iguassu Falls • Rio de Janeiro motor coach • Farewell reception • On board escort & on-site coor- Cost: $6,675 CDN (per person/double occupancy) dination • 3 breakfasts • 3 dinners Explore his brilliance! Cost: $760 CDN (per person/double occupancy) EXPEDITIONS Best ski trails East of the Rockies! Mozart’s Imperial Cities — ADVENTURE Praque, Salzburg & Vienna Ski Mont Sainte-Anne April 30 — May 16, 2004 March 1 — March 6, 2004 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in It’s March Break, time to hit the slopes of Mont Saint-Anne! Mont Salzburg, Austria, in 1759. -

Pipeline's Shutdown Exposes Cyber Threat to Power Sector

P2JW130000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ADVERTISEMENT Wonderingwhatitfeels like to finally roll over your old 401k? Find outhow our rolloverspecialists canhelpyou getthe ball rolling on page R6. ***** MONDAY,MAY 10,2021~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.108 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 Last week: DJIA 34777.76 À 902.91 2.7% NASDAQ 13752.24 g 1.5% STOXX 600 444.93 À 1.7% 10-YR. TREASURY À 16/32 , yield 1.576% OIL $64.90 À $1.32 EURO $1.2163 YEN 108.59 Kabul Mourns Victims of Attack That Struck at Schoolgirls Shoppers What’s News Feel Bite As Prices Business&Finance Begin mericans accustomed Ato years of low infla- tion are beginning to pay To Climb sharply higher prices for goods and services as the economy strains to rev up Companies arepassing and the pandemic wanes. A1 on the pain of supply Investors in search of shortages and rising higher returns and lower taxes are scooping up debt costsof ingredients sold by stateand local gov- S ernments, pushing borrowing PRES BY JAEWON KANG coststonear-recordlows. A1 TED Star Entertainment OCIA Americans accustomed to SS said it wantstomerge with /A yearsoflow inflation arebegin- casino operator CrownRe- ning to paysharply higher sorts, which has also re- ZUHAIB prices forgoods and services as ceived asweetened bid M the economystrains to revup from Blackstone Group. B1 and the pandemic wanes. MARIA GRIEF:MournersonSundayattendafuneral forone of 53 people killedSaturdayinabombing thattargetedschoolgirls in a Pricetagsonconsumer Policymakers debated the predominantly Shiiteneighborhood in Kabul. The Afghan president blamedthe Taliban. The Taliban deniedresponsibility.A8 goods from processed meat to root cause of a growing dishwashing productshave shortage of workers that risen by double-digit percent- threatens to restrain the pace ages from ayear ago, according of U.S.