Basic Guide to the National Labor Relations Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genora and Sol Dollinger Papers

Genora and Sol Dollinger Collection Papers, 1914-1995 (Predominantly, 1940s-1980s) 5 linear feet 5 storage boxes Accession #633 DALNET # OCLC # The papers of Genora and Sol Dollinger were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in December of 1995 by Sol Dollinger and were opened for research in November of 1998. Genora Johnson Dollinger was born April 20, 1913 and grew up in Flint, Michigan, the eldest daughter of middle-class businessman, Raymond Albro and his wife, Lora. In 1930 she married Kermit Johnson, whose father Carl introduced her to radical politics, and a year later became a charter member of the Flint Socialist Party. She gained fame as the organizer of Flint Women’s Auxiliary #10 and the Women’s Emergency Brigade, which helped the UAW win the sit-down strike against General Motors in 1936-1937 that marked a major turning point in American labor history. Her husband led the strike at the Chevrolet engine plant No. 4. In 1941 Genora Johnson met fellow Socialist, Sol Dollinger, and a year later they were married. Solomon Dollinger was born in Youngstown, Ohio October 7, 1920 and grew up in New York City. At fifteen, he followed his older brother’s example and joined the Young People’s Socialist League. He worked for the WPA and as a union organizer with his brother before getting his sailor’s papers in 1941. In the 1940s and ‘50s he found work as a merchant seaman and in the automobile plants and organized for the Socialist Workers Party in Flint. -

Reconciling Collective Bargaining with Employee Supervision of Management

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 137 NOVEMBER 1988 No. 1 ARTICLES RECONCILING COLLECTIVE BARGAINING WITH EMPLOYEE SUPERVISION OF MANAGEMENT MICHAEL C. HARPERt I. INTRODUCTION A. The Challenge of Industrial Democracy The realities of economic organization in modern industrial states pose a critical dilemma for all who care about democratic ideals. Tech- nological developments and attendant complicated divisions of work have enabled these states to transform their citizens' standards of living; such developments have also, however, brought hierarchical economic organizations' that are unresponsive to the influence of most individual employees. A society that claims to be democratic cannot ignore this t Professor of Law, Boston University. The author wishes to thank participants in faculty workshops at Boston University and Northeastern University law schools, as well as Thomas Kohler, for their comments on an earlier draft of this Article. I also wish to thank Lori Bauer for her research assistance. I I See M. WEBER, THE THEORY OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ORGANIZATION 245-48 (T. Parsons ed. 1947). 2 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 137:1 condition.' Enhancing individuals' control over their own lives requires institutions that will facilitate democratic decisionmaking about eco- nomic production as well as governmental authority. This Article contributes to thought about such institutions by inte- grating two potentially conflicting strategies to mitigate modern hierar- chical -

Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?

William & Mary Law Review Volume 2 (1959-1960) Issue 1 Article 3 October 1959 Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible? J. T. Cutler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Repository Citation J. T. Cutler, Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?, 2 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 16 (1959), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/3 Copyright c 1959 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr UNION SECURITY AND RIGHT-TO-WORK LAWS: IS CO-EXISTENCE POSSIBLE? J. T. CUTLER THE UNION STRUGGLE At the beginning of the 20th Century management was all powerful and with the decision in Adair v. United States1 it seemed as though Congress was helpless to regulate labor relations. The Supreme Court had held that the power to regulate commerce could not be applied to the labor field because of the conflict with fundamental rights secured by the Fifth Amendment. Moreover, an employer could require a person to agree not to join a union as a condition of his employment and any legislative interference with such an agreement would be an arbitrary and unjustifiable infringement of the liberty of contract. It was not until the first World War that the federal government successfully entered the field of industrial rela- tions with the creation by President Wilson of the War Labor Board. Upon being organized the Board adopted a policy for- bidding employer interference with the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively and employer discrimination against employees engaging in lawful union activities2 . -

Governing Body 323Rd Session, Geneva, 12–27 March 2015 GB.323/INS/5/Appendix III

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE Governing Body 323rd Session, Geneva, 12–27 March 2015 GB.323/INS/5/Appendix III Institutional Section INS Date: 13 March 2015 Original: English FIFTH ITEM ON THE AGENDA The Standards Initiative – Appendix III Background document for the Tripartite Meeting on the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87), in relation to the right to strike and the modalities and practices of strike action at national level (revised) (Geneva, 23–25 February 2015) Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Decision on the fifth item on the agenda: The standards initiative: Follow-up to the 2012 ILC Committee on the Application of Standards .................. 1 Part I. ILO Convention No. 87 and the right to strike ..................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 II. The Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87) ......................................................................... 3 II.1. Negotiating history prior to the adoption of the Convention ........................... 3 II.2. Related developments after the adoption of the Convention ........................... 5 III. Supervision of obligations arising under or relating to Conventions ........................ -

Rethinking Precarity and Capitalism: an Interview with Charlie Post

Rethinking Precarity and Capitalism | 247 Rethinking Precarity and Capitalism: An Interview with Charlie Post Jordy Cummings1 (JC): The theme of this year’s Alternate Routes is the “paradox of low-wage, no-wage work”, and there is a great deal of analysis of an allegedly new historical subject, “the precariat”. What do you make of this “paradox”? Is capitalism really that different in 2015 than it was 20, 30, 40 years ago? Charlie Post2 (CP): Capitalism is certainly different today than it was during the so-called “Golden Age” of 1945-1975. During those years, “full-employment” – unemployment below the “frictional” rate of 3-4 percent, the dominance of full-time work with unemployment insurance, health care, pensions and the like (provided by the state, private employers, or some combination) – was the norm. This “full-employment” model also included some measure of job security – either legal or contractual protections from arbitrary dismissal, etc. The “Golden Age” was, in my opinion, exceptional in the history of capitalism. It was the product of a combination of a long period of rising profitability (1933-1966) and a militant labor movement across the industrialized world. Workers had threatened the foundations of capitalist rule (France and Spain in the mid-1930s, France and Italy immediately after World War II, France in 1968, Portugal 1974-1975) or severely disrupted capitalist accumulation in mass strike waves in the mid-1930s, immediate post-war years and again between 1965-1975. Capital was forced to make major concessions to labor. The “full-employment” model and the expansive welfare state were the most important gains, giving workers unprecedented security of employment. -

National Master Ups Freight Agreement

NATIONAL MASTER UPS FREIGHT AGREEMENT For the Period: August 1, 2013 2018 through July 31, 2018 2023 covering: The parties reserve the right to correct inadvertent errors and omissions. Where no reference is made to a specific Article or Section thereof, such Article and Section are to continue as in the current Master Agreement, as applied and interpreted during the life of such Agreement. Additions and new language are bold and underlined. Language from the prior Master Agreement that is being deleted is struck through. UPS Freight, herein referred to as the “Employer” and/or employees who are not members of the Local Union and all “Company”, and the TEAMSTERS NATIONAL UPS FREIGHT employees who are hired hereafter, shall become and remain NEGOTIATING COMMITTEE, hereinafter referred to as members in good standing of the Local Union as a condition TNUPSFNC, representing Local Unions affiliated with the of employment on and after the thirty-first (31st) day following International Brotherhood of Teamsters. the beginning of their employment, or on and after the thirty- first (31st) day following the effective date of this subsection, or ARTICLE 1 the date of this Agreement, whichever is the later. An employee PARTIES TO THE AGREEMENT who has failed to acquire, or thereafter maintain, membership in the Union, as herein provided, shall be terminated seventy-two Section 3. Transfer of Company Title or Interest (72) hours after the Employer has received written notice from In the event the Company is sold or any part of its operations covered an authorized representative of the Local Union, certifying that by this Agreement is transferred, the Company shall give notice to the membership has been, and is continuing to be offered to such Local UnionTNUPSFNC to the extent required by applicable law. -

Employee Free Choice Act—Union Certification

S. HRG. 108–596 EMPLOYEE FREE CHOICE ACT—UNION CERTIFICATION HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARING JULY 16, 2004—HARRISBURG, PA Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 95–533 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS TED STEVENS, Alaska, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ERNEST F. HOLLINGS, South Carolina CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky TOM HARKIN, Iowa CONRAD BURNS, Montana BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HARRY REID, Nevada JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire HERB KOHL, Wisconsin ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah PATTY MURRAY, Washington BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JAMES W. MORHARD, Staff Director LISA SUTHERLAND, Deputy Staff Director TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON DEPARTMENTS OF LABOR, HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, AND EDUCATION, AND RELATED AGENCIES ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi TOM HARKIN, Iowa JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ERNEST F. -

Capitalist Meltdo-Wn

"To face reality squarely; not to seek the line of least resistance; to call things by their right names; to speak t�e truth to the masses, no matter how bitter it may be; not to fear obstacles; to be true in little thi�gs as in big ones; to base one's progra.1!1 on the logic of the class struggle;. to be bold when the hour of action arrives-these are the rules of the Fourth International." 'Inequality, Unemployment & Injustice' Capitalist Meltdo-wn Global capitalism is currently in the grip of the most The bourgeois press is relentless in seizing on even the severe economic contraction since the Great Depression of smallest signs of possible "recovery" to reassure consumers the 1930s. The ultimate depth and duration of the down and investors that better days are just around thecomer. This turn remain to be seen, but there are many indicators that paternalistic" optimism" recalls similar prognosticationsfol point to a lengthy period of massive unemployment in the lowing the 1929 Wall Street crash: "Depression has reached imperialist camp and a steep fall in living standards in the or passed its bottom, [Assistant Secretary of Commerce so-called developing countries. Julius] Klein told the Detroit Board of Commerce, although 2 'we may bump along' for a while in returningto higher trade For those in the neocolonies struggling to eke out a living levels " (New Yo rk Times, 19 March 19 31).The next month, on a dollar or two a day, this crisis will literally be a matter in a major speech approved by President Herbert Hoover, of life and death. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

Featherbedding on the Railroads: by Law and by Agreement·

Featherbedding on the Railroads: by Law and by Agreement· J.A. LlPOWSKI* I. INTRODUCTION The concept of "featherbedding"1 or make-work rules involves the conflict between two ideals: efficiency, usually necessary for the profit able operation of an enterprise, and job security, which is the desire of every worker and the hope of any union interested in maintaining its membership rolls. These conflicting ideals must be reconciled at some point. In the railroad industry, where the controversy over featherbedding has been most pronounced and the consequences most strongly felt, the carriers argue that the increased labor cost resulting from this practice is crippling the industry. In 1963 it was estimated that featherbedding . • BA, Lindenwood College; J.D., University of Tulsa College of Law, 1976. 1. Featherbedding has been defined as "[T]hose work rules which require the employ ment of more workers than needed for the job. In addition, when technological advances eliminate positions, unions often insist that the workers be retained and receive their regular pay tor doing nothing" A PARADIS, THE LABOR REFERENCE BOOK 71 (1972). The United States Departm'ent of Labor says that featherbedding is: a derogatory term applied to a practice, working rule, or agreement provision which limits output or requires employment of excess workers and thereby creates or preserves soft or unnecessary jobs; or to a charge or fee levied by a union upon a company for services which are not performed or not to be performed. U.S. DEPT. OF LABOR, BULL. No. 1438. GLOSSARY OF CURRENT INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS AND WAGE TERMS 31 (1965). -

Why Organize and Affiliate Others?

Affiliate Organizing Committee Handbook Updated March, 2016 WHY ORGANIZE AND AFFILIATE OTHERS? ........................................................1 - 2 CSO CODE OF CONDUCT ...................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION TO CSO/NSO ...........................................................................4 BENEFITS OF CSO MEMBERSHIP AND LOCAL AFFILIATION .................................5 HOW MEMBERS PARTICIPATE IN CSO/NSO ........................................................6 - 7 ELIGIBILITY, DUES AND STANDARDS FOR AFFILIATION ....................................8 - 9 REPRESENTING A BRAND-NEW BARGAINING UNIT .......................................... 10 - 15 BARGAINING CSO AGREEMENTS .......................................................................16 ONCE THE CONTRACT HAS BEEN BARGAINED ...................................................17 APPENDIX A – AUTHORIZATION FORM ..............................................................19 APPENDIX B – RECOGNITION REQUEST ............................................................20 APPENDIX C – RECOGNITION AGREEMENT ........................................................21 APPENDIX D – NLRB RECOGNITION PETITION ...................................................22 APPENDIX E – CBC GOALS AND SETTLEMENT STANDARDS ........................23 - 31 CSO MEMBERSHIP FORM ..............................................................................33 1 CSO Affiliate Organizing Handbook Welcome to the California Staff Organization (CSO). -

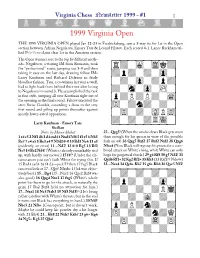

1999/1 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #1 1 1999 Virginia Open THE 1999 VIRGINIA OPEN played Jan 22-24 in Fredricksburg, saw a 3-way tie for 1st in the Open section between Adrian Negulescu, Emory Tate & Leonid Filatov. Each scored 4-1. Lance Rackham tal- 1 1 lied 5 ⁄2- ⁄2 to claim clear 1st in the Amateur section. The Open winners rose to the top by different meth- ‹óóóóóóóó‹ ods. Negulescu, a visiting IM from Rumania, took õÏ›‹Ò‹ÌÙ›ú the “professional” route, jumping out 3-0 and then taking it easy on the last day, drawing fellow IMs õ›‡›‹›‹·‹ú Larry Kaufman and Richard Delaune in fairly bloodless fashion. Tate, a co-winner last year as well, õ‹›‹·‹›‡›ú had to fight back from behind this time after losing to Negulescu in round 3. He accomplished the task õ›‹Â‹·‹„‹ú in fine style, jumping all over Kaufman right out of õ‡›fi›fi›‹Ôú the opening in the final round. Filatov executed the semi Swiss Gambit, conceding a draw in the very õfl‹›‰›‹›‹ú first round and piling up points thereafter against mostly lower-rated opposition. õ‹fl‹›‹Áfiflú õ›‹›‹›ÍÛ‹ú Larry Kaufman - Emory Tate Sicilian ‹ìììììììì‹ Notes by Macon Shibut 25...Qxg5! (When the smoke clears Black gets more 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 f3 e5 6 Nb3 than enough for his queen in view of the possible Be7 7 c4 a5 8 Be3 a4 9 N3d2 0-0 10 Bd3 Nc6 11 a3 fork on e4) 26 Qxg5 Rxf2 27 Rxf2 Nxf2 28 Qxg6 (evidently an error) 11...Nd7! 12 0-0 Bg5 13 Bf2 Nfxe4 (Now Black will regroup his pieces for a com- Nc5 14 Bc2 Nd4! (White is already remarkably tied bined attack on White’s king, while White can only up, with hardly any moves.) 15 f4!? (Under the cir- hope for perpetual check.) 29 g4 Rf8 30 g5 Nd2! 31 cumstances you can’t fault White for trying this.