LSM-Ithaka-GB-TFV-Opt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronologie De La Guinée Bissau

Chronologie de la Guinée Bissau (24 septembre : )Le Parti africain de l’indépendance de la Guinée-Bissau et du Cap-Vert (PAIGC) proclame la République. Formation d’un Conseil d’Etat dirigé par Luis Cabral. 1974 (10 septembre) : Reconnaissance de l’indépendance par le Portugal. Luis Cabral est président. 1974 (15 octobre) : Départ des dernières troupes portugaises. 1975 (18 mai) Nationalisation des terres urbaines et rurales. 1976 (29 février) La Guinée Bissau émet sa monnaie, le peso. 1977 (13 mars) Réélection par l’Assemblée nationale populaire de Luis Cabral à la présidence du Conseil d’Etat. 1978 (7 juillet) Décès de Francisco Mendes. Commissaire principal (chef du gouvernement) depuis 1973, il avait été reconduit dans ses fonctions en 1977. 1978 (28 septembre) : Joâo Bernado Vieira est nommé chef du gouvernement. 1980 (18 octobre) Projet de Constitution élaboré par le PAIGC et l’Assemblée nationale. 1980 (15 novembre) : Coup d’Etat militaire du commandant Joâo Bernado Vieira. Il préside le Conseil de la Révolution. 1981 (7/14 novembre) : Premier congrès extraordinaire du PAIGC. 1982 (17 mai) Victor Saúde Maria est nommé Premier ministre. 1983 (23 décembre) : Dévaluation de 50 % du peso. 1984 (12 mars) Victor Saúde Maria, accusé de préparer un coup d’Etat, est démis de ses fonctions. Le poste de Premier ministre est supprimé. 1984 (31 mars) Election des conseillers régionaux chargés d’élire les députés de l’Assemblée nationale populaire. 1984 (13 mai) Adoption d’une nouvelle Constitution. 1984 (13 mai) Joâo Bernado Vieira est élu président du Conseil d’Etat et cumule les fonctions de chef de l’Etat et de chef du gouvernement. -

Tamilton Gomes Teixeira

Análise Histórica e Social do Conflito e da Instabilidade Política na Guiné- Bissau e suas Configurações (1980-2019) Tamilton Gomes Teixeira Mestrado em Sociologia Orientador(a): Doutora Clara Carvalho, Professora Associada, ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Dezembro, 2020 i Análise Histórica e Social do Conflito e da Instabilidade Política na Guiné- Bissau e suas Configurações Tamilton Gomes Teixeira Mestrado em Sociologia Orientador(a): Doutora Clara Carvalho, Professora Associada, ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Dezembro, 2020 ii AGRADECIMENTOS Aos meus ancestrais de baraca de fanado de Bolama. Aos meus pais pelo apoio de sempre. À minha orientadora Prof. Clara Carvalho por tudo que em mim desperta, pela sua compreensão todas as vezes que não pude cumprir calendário por conta dos meus apertos para me manter em Lisboa, razão pela qual as possíveis imperfeições deste trabalho são apenas minhas. Aos colegas, Armando, Trindade, Vanita e Babiro que me acompanharam nesse árduo caminho, novo desafio, num país que me ensinou muito mais que o mestrado. Ao meu tio Evanildo, a minha amiga Neya. À minha prima Libania, que me ofereceu teto enquanto procurava uma casa para alugar. Fico grato! À minha irmã Tanelsia e Tania, por tudo. Ao Tony Tchecka, pela amizade, carinho, inspiração e por me ter ensinado sempre e a cada conversa sobre a Guiné. À minha parceira, Siozimila, responsável por eu não ter desistido, por todas as vezes que me confortou com um simples “são fases”, durante esse tempo em que se dividiu em pai e mãe para a nossa pequena Egypcia. Mas, sobretudo, por me compreender como ninguém, mesmo quando não sou palavra. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Mamudo Djanté

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESTADO DO RIO DE JANEIRO CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS JURÍDICAS E POLÍTICAS - CCJP Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência Política - PPGCP Mamudo Djanté Cooperação Bilateral Brasil/Guiné-Bissau: Uma análise no âmbito da cooperação Sul- Sul (1974-2016). Rio de Janeiro 2019 Mamudo Djanté Cooperação Bilateral Brasil/Guiné-Bissau: Uma análise no âmbito da cooperação Sul- Sul (1974-2016). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência Política - PPGCP da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência Política. Área de concentração: Relações Internacionais e Política Mundial. Orientador: Prof. Dr. André Luiz Coelho Farias de Souza Rio de Janeiro 2019 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Autorizo apenas para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução parcial ou total desta dissertação, desde que citada à fonte. ________________________ _________________ Assinatura Data FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO Mamudo Djanté Cooperação Bilateral Brasil/Guiné-Bissau: Uma análise no âmbito da cooperação Sul- Sul (1974-2016). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência Política - PPGCP da Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência Política. Área de concentração: Relações Internacionais e Política Mundial. BANCA EXAMINADORA: __________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. André Luiz Coelho Farias de Souza (orientador) Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - UNIRIO __________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fabricio Pereira da Silva Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - UNIRIO __________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Emerson Maione de Souza Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - UFRJ Aprovada em: _____ de _______________ de 2019 DEDICATÓRIA Ao meu querido falecido pai, Baba Djanté, a pessoa que se mais orgulhava de mim. -

Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: the Group of Women Facilitators

Monday street market in downtown Bissau, November 13, 2017. Bissau, Guinea-Bissau Photo: Beatriz Bechelli Policy Brief Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: The Group of Women Facilitators Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE | POLICE BRIEF | APRIL 2018 Policy Brief Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: Group of Women Facilitators Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute1 Key Recommendations • Identify the challenges and opportunities inherent to participating in the Group of Women Mediators (GMF) and how hurdles could be overcome. • Ensure the personal safety of the group’s current and prospective members and support ways to make it feasible for the women to participate on an ongoing basis. • Support and encourage the safe documentation of the GMF activities. • Promote stronger linkages to other women’s groups in Guinea-Bissau, including the Network of Women Mediators and the Network of Parliamentary Women (Rede de Mulheres Parlamentares, RMP). • Strengthen links to regional organizations such as WIPNET and ECOWAS and to global institutions such as the UN, especially via the UNWomen, DPA, and UNIOGBIS, focusing on capacity-building, knowledge-sharing, and drawing lessons learned. • Promote South-South cooperation on mediation and facilitation by creating links to other women’s groups elsewhere in Africa, including other Lusophone countries. 1 Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: The Group of Women Facilitators Introduction On July 10, 2017, the President of Guinea Bissau, José Mário Vaz, met politician Domingos Simões Pereira, who had served as Prime Minister from 2014 to August 2015. Although Pereira remained head of the country’s major political party, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cabo Verde (PAIGC), he had been dismissed (along with the entire cabinet) by the president in August 2015 during a power struggle between the two men. -

Women Fighters and National Liberation in Guinea Bissau Aliou Ly

24 | Feminist Africa 19 Promise and betrayal: Women fighters and national liberation in Guinea Bissau Aliou Ly Introduction Guinea Bissau presents an especially clear-cut case in which women’s mass participation in the independence struggle was not followed by sustained commitment to women’s equality in the post-colonial period. Amilcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau and his party, the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), realised that the national liberation war could not succeed without women’s participation, not only as political agents but also as fighters. Cabral also understood, and attempted to convince his male Party members, that a genuine national liberation meant liberation not only from colonialism but also from all the local traditional socio-cultural forces, both pre-colonial and imposed by the Portuguese rulers, that excluded women from decision-making structures at every level of society. Sadly, many of the former women fighters also say that male PAIGC members did not fulfil promises of socio-political, economic and gender equality that were crucial to genuine social transformation. Because women participated in bringing about independence in very dramatic ways, because the Party that came to power actually promised equality, and because the Party then had women return to their traditional subordinate roles, Guinea Bissau provides an especially clear case for exploring the relation in Africa between broken promises to women and the unhappiness reflected in the saying “Africa is growing but not developing”. In May 2013, Africa’s Heads of State celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the Organisation of African Unity in a positive mood because of a rising GDP and positive view about African economies. -

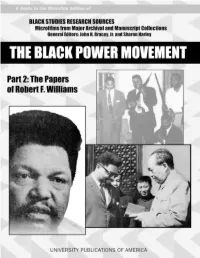

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Download the List of Participants

46 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Socialfst International BULGARIA CZECH AND SLOVAK FED. FRANCE Pierre Maurey Bulgarian Social Democratic REPUBLIC Socialist Party, PS Luis Ayala Party, BSDP Social Democratic Party of Laurent Fabius Petar Dertliev Slovakia Gerard Fuchs Office of Willy Brandt Petar Kornaiev Jan Sekaj Jean-Marc Ayrault Klaus Lindenberg Dimit rin Vic ev Pavol Dubcek Gerard Collomb Dian Dimitrov Pierre Joxe Valkana Todorova DENMARK Yvette Roudy Georgi Kabov Social Democratic Party Pervenche Beres Tchavdar Nikolov Poul Nyrup Rasmussen Bertrand Druon FULL MEMBER PARTIES Stefan Radoslavov Lasse Budtz Renee Fregosi Ralf Pittelkow Brigitte Bloch ARUBA BURKINA FASO Henrik Larsen Alain Chenal People's Electoral Progressive Front of Upper Bj0rn Westh Movement, MEP Volta, FPV Mogens Lykketoft GERMANY Hyacinthe Rudolfo Croes Joseph Ki-Zerbo Social Democratic Party of DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Germany, SPD ARGENTINA CANADA Dominican Revolutionary Bjorn Entolm Popular Socialist Party, PSP New Democratic Party, Party, PRD Hans-Joe en Vogel Guillermo Estevez Boero NDP/NPD Jose Francisco Pena Hans-Ulrich Klose Ernesto Jaimovich Audrey McLaughlin Gomez Rosemarie Bechthum Eduardo Garcia Tessa Hebb Hatuey de Camps Karlheinz Blessing Maria del Carmen Vinas Steve Lee Milagros Ortiz Bosch Hans-Eberhard Dingels Julie Davis Leonor Sanchez Baret Freimut Duve AUSTRIA Lynn Jones Tirso Mejia Ricart Norbert Gansel Social Democratic Party of Rejean Bercier Peg%:'. Cabral Peter Glotz Austria, SPOe Diane O'Reggio Luz el Alba Thevenin Ingamar Hauchler Franz Vranitzky Keith -

A Problemática Do Sistema De Governo Na Guiné-Bissau

UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA Faculdade de Direito A Problemática do Sistema de Governo na Guiné-Bissau Trabalho de investigação apresentado no âmbito do Mestrado em Direito: Especialidade em Ciências Jurídico-Forenses Aluno: Aníran Ykey Pereira Kafft Kosta Orientador: Professor Doutor João Carlos Simões Gonçalves Loureiro Coimbra, 2016 Índice Lista de Siglas / Abreviaturas ................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUÇÃO ..................................................................................................................... 4 I. ANÁLISE: TIPOS DE SISTEMAS DE GOVERNO ................................................ 6 1. SISTEMA PARLAMENTAR.................................................................................... 6 1.1. NOÇÃO................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. CARACTERÍSTICAS ............................................................................................ 6 1.3. VANTAGENS ........................................................................................................ 9 1.4. DESVANTAGENS ................................................................................................. 9 2. SISTEMA PRESIDENCIAL ................................................................................... 11 2.1. NOÇÃO................................................................................................................. 11 2.2. CARACTERÍSTICAS ......................................................................................... -

Women As Ministers and the Issue of Gender Equality in the Republic of Cape Verde

Afrika Zamani, Nos 18 & 19, 2010–2011, pp. 151–160 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa & Association of African Historians, 2013 (ISSN 0850-3079) Women as Ministers and the Issue of Gender Equality in the Republic of Cape Verde Ângela Sofia Benoliel Coutinho* Abstract In the year 2008, the Republic of Cape Verde was considered the nation with the second most gender equal government in the world, as its governmental index was composed of eight female ministers, seven male ministers, a male prime minister, and four male secretaries of state. This article investigates gender equality in government by analysing the proportion of women that occupy leadership positions in the ministries, the judiciary, diplomatic service and those in the legislative assembly and local governments. The objective of this article is to seek to discover the point to which the governmental gender equality statistics mirrors the reality of contemporary Cape Verdean society as a whole. In light of this data, is it legitimate to conclude that this is an egalitarian society? What trajectory did the Cape Verdean society undergo that led to this situation? Résumé En 2008, la république du Cap-Vert a été considérée comme le deuxième pays au monde qui respecte le plus la parité au sein de son gouvernement parce qu’il était composé de huit femmes ministres, sept hommes ministres, un homme Premier ministre, et quatre homme ministres d’État. Cet article étudie l’égalité entre les sexes au sein du gouvernement en analysant la proportion de femmes qui occupent des postes de direction dans les ministères, au niveau du pouvoir judiciaire, des services diplomatiques et dans les collectivités locales et au niveau du pouvoir législatif. -

Convict Leasing and the Construction of Carceral

RAGGED BATTALIONS, PLOTTING LIBERTY: CONVICT LEASING AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF CARCERAL CAPITALISM IN FLORIDA, 1875-1925 E. Carson Eckhard AN HONORS THESIS in HIstory Presented to the Faculty of the Department of HIstory of the UniversIty of Pennsylvania in PartIal Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts wIth Honors 2021 Warren Breckman, Honors Seminar Director Mia Bay, Thesis Advisor _____________________________ Sinyen Fei Undergraduate Chair, Department of History I Acknowledgements This project would not have been possIble wIthout the many people who supported me along the way. I would lIke to thank my advisors, MIa Bay and Warren Breckman for theIr constant support, encouragement and feedback on every draft. I am also grateful to the Andrea MItchell Center for the Study of Democracy, whose financIal support made my archival research possIble. I would also lIke to thank Jeff Green, Matt Shafer, GIdeon Cohn-Postar and Paul Wolff MItchell for theIr feedback and support throughout this Process. Thank you also to Scott WIlds for his genealogical assIstance, on this project and on others throughout my tIme at Penn. I would also lIke to thank Kathleen Brown for InsPIring me to pursue historical research and supportIng me these past four years, and Gabriel Raeburn, for IntroducIng me to Penn’s HIstory Department. AdditIonally, NatalIa Rommen and MIsha McDaniel’s love, lIstening and support empowered me throughout this project. Lastly, I am endlessly grateful to my famIly and friends, whose encouragement and patIence made this process possIble and enjoyable. I am especIally thankful for my grandparents, Janie and Harry ClIne, who have nurtured my love of history sInce I was a child. -

National Reconstruction in Guinea-Bissau

Sowing the First Harvest: National Reconstruction in Guinea-Bissau http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.lsmp1013 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Sowing the First Harvest: National Reconstruction in Guinea-Bissau Author/Creator Sarrazin, Chantal and Ole Gjerstad Publisher LSM Date 1978-00-00 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Guinea-Bissau Coverage (temporal) 1959 - 1975 Source Candice Wright Rights By kind permission of the Liberation Support Movement. Description INTRODUCTION. Chapter One-ASPECTS OF A DIFFICULT TRANSITION. Chapter Two-'SINCE PIDJIGUITI WE NEVER LOOKED BACK'. Chapter Three-'WE DON'T ACCEPT BEING TREATED LIKE ANIMALS'.