Development Issues for the Creative Economy in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blu Jaz Food Menu(Dd 19.01.15)

FOOD MENU 1. Mediteranean 3-6 2. Local Delights 7 3. Continental 8 4. Finger Food 9 5. Wraps / Hotdogs / Burgers / Sandwiches 10 6. Pastas 11 7. Meat And Seafood 12 8. Desserts And Pastries 13 “Enjoy Your Meals” Opening Hours Monday to Thursday (12 Noon to 1 am) Friday (12 Noon to 2 am) Saturday (4 pm to 2 am) Closed on Sunday & Public Holiday (Except Fridays & Saturdays) Venues & Event Spaces BluBlu JazJaz 2nd LevelLevel Blu Jaz 3rd Level Piedra Negra 2nd Level Blu Jaz & Piedra Negra Venues are available to host : Private Events, Corporate Events, Birthday Party, Music Events, Town Hall Meetings. Please Contact: 9199 0610 Or Drop email at: [email protected] For more information please visit: www.blujazcafe.net MEDITERANEAN SOUP 01. Lentil Soup 6.00 SALAD 02. Shepherd’s Salad 8.00 diced cucumber, white onions, tomatoes, chopped green chillies, parsley and mint leaves with basil vinaigrette dressing 03. Village Salad 8.50 mesclun salad, tossed with chickpeas, black olives, feta cheese, cucumber, tomatoes and bell peppers with vinaigrette dressing (All Soup and Salads are served with lightly toasted bread) #03 Last Order At: 11:30 pm (Mon to Thu), 1:30 am (Fri And Sat) Prices Are Subject To 10% Service And Prevailing GST Pg 3 PITA BREAD WITH DIPS 4. Pita Bread 5” (1 pc) 1.50 Add Choice of Dips 05. Hummus (Chick Peas) 5.00 chickpeas and tahini sauce with olive oil, lemon juice, fresh garlic and house spices top with paprika & chick peas. 06. Baba Ghanoush (Aubergine) 5.00 roasted aubergine mixed with greek yoghurt, olive oil, lemon juice and garlic top with paprika & olive oil. -

STB Singapore Insider 2017

39036SIAG_Brand13_Venice_148x210_SG Insider_Apr17_Inc.indd 1 28/3/17 10:19 AM HANDY TIPS 02 Useful information Happy about Singapore birthday, WHAT’S ON 04 Exciting events in Singapore! the months ahead The Lion City turns 52 on 9 August, and you’re about to witness a slew of fun-filled festivities across the island RETAIL THERAPY during this period. 20 Singapore’s shopping hotspots and what to Aside from celebrating buy from there Singapore’s birthday at the National Day Parade with COVER STORY spectacular firework displays 11 Illustrator Eeshaun to look out for, the 2017 shares his favourite spots FORMULA 1 SINGAPORE in Singapore ARILINES SINGAPORE GRAND PRIX rolls into town – DAY TRIPPER bringing you a thrilling weekend 12 These day and night tours of electrifying live performances will show you alternative and exhilarating action on and sides of Singapore THE EAT LIST off the track. 24 Hawker highlights and the hottest tables in town What’s more? Revel in the celebrations of art at the Singapore Night Festival BY NIGHT and Singapore International 28 Cool bars and clubs to Festival of Arts. Also, not to be drink and be merry missed is the oh-so-popular Epicurean Market where a rare gastronomic affair awaits at Marina Bay Sands. But the fun doesn’t stop there – with plenty more exciting gigs, parties, shopping events and new restaurants on the ESSENTIAL 14 SINGAPORE horizon, Singapore will leave you FAMILY FUN breathless, that’s for sure! City must-dos and neighbourhood guides 30 Things to do with for every visitor the little ones FOUNDER Chris Edwards THE HONEYCOMBERS STB is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness [email protected] or usefulness of this publication and shall not be MANAGING DIRECTOR Hamish Mcdougall liable for any damage, loss, injury or inconvenience HO PRINTING SINGAPORE PTE LTD arising from or in connection with the content of EDITOR Zakaria Muhammad 31 Changi South Street 1 Singapore 486769 this publication. -

Legalize Same-Sex Marriage?

JULY 2015 ittle anilaConfidential L M LEFT, Michelle Beloso and Ampee Panaligan walked as Reinas in the Santacruzan. FAR RIGHT, Kapami- . lya’s Erich Gonzales added glamour to the festival. PISTAHAN SA TORONTO 2015 Glamorized and a smashing Success Legalize same-sex Marriage? Chances are Slim and None MANILA - Congress isn’t keen on passing a law legalizing same-sex unions despite the growing acceptance for lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders (LGBT) in the Philippines. No less than House Speaker Feliciano Belmonte Jr. himself thumbed down the idea of legalizing same- sex marriages, which are now deemed legal in the United States. “Definitely I’m against [it],” he said in a text message. Belmonte’s opposition was shared by male colleagues in the House, who noted that the chances of a bill on same-sex unions being passed is next to none considering that even the proposal to SAME SEX MARRIAGE continued on page 21 ABOVE-GMA7 Kapuso star Heart Evangelista poses with Miss Philippines Canada 2015 Nathalie Ramos and Miss Philippines Canada 2014 titlist Krisgelle Maramot. PHOTO BY ALBERT ALO PHOTO ON RIGHT Top L-R: Miss Teen Philippines Canada 2015 - Ansha Hipolito, GMA Pinoy TV star who crowned the winners - Heart Evangelista, Miss Philippines Canada 2015 - Nathalie Ramos, Mrs Philippines Canada 2015 - Ning Talandato, Little Miss Philippines Canada 2015 - Angeli Lachica Bottom L-R: Little Mr. Philippines Canada aka Pinoy Bulilit - Edward Jones, Miss Phil-Can first runner up 2015 - Audrey Bushell, Mrs Phil-Can first runner up 2015 - Reyna Laciste and Little Miss Phil-Can first runner up 2015 - Jasmin Flores PHL has worse food in MEN IN WHITE Asia Malaysian Chef Wan turns his nose up at CNN’s food ranking KUALA LUMPUR: Chef Wan feels that fact that he is Malaysian himself, his reasoning Malaysia should have clinched the top spot on was sound enough: “I see food as varieties and CNN’s “Which destination has the world’s best flavours that reflect the culture and food, and food?” poll published three days ago. -

Awareness and Willingness for Engagement of Youth on World Heritage Site: a Study on Lenggong Archaeological Site

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 22; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Awareness and Willingness for Engagement of Youth on World Heritage Site: A Study on Lenggong Archaeological Site Mastura Jaafar1, Shuhaida Md Noor2 & S. Mostafa Rasoolimanesh1 1 School of Housing, Building, and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia 2 School of Communication, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia Correspondence: S. Mostafa Rasoolimanesh, School of Housing, Building, and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia. Tel: 60-4-653-5278. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 15, 2014 Accepted: September 17, 2014 Online Published: October 30, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n22p29 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n22p29 Abstract Lenggong Valley was recognised as a World Heritage Site in June 2012. The literature highlights the importance of community engagement in conservation programmes. Principally, the involvement of young people is necessary to facilitate heritage management programmes. The readiness of youth to engage can be measured from their awareness and willingness to participate. For this study, we administered questionnaire surveys to 175 respondents from three secondary schools in Lenggong. The results revealed a low level of awareness and a lack of willingness for participation. In addition, the findings suggest an uncertain correlation between awareness and willingness for participation among youth. Keywords: awareness, community engagement, Lenggong valley, World Heritage Site (WHS), youth, willingness 1. Introduction Heritage is frequently defined as our inheritance from the past, what endures into the present, and what continues into the future; allowing generations to gain knowledge, wonder at and benefit from (UNESCO, 1998, 2002). -

![Pencapaian Filem Cereka Tempatan Di Peringkat Antarabangsa (1950-2017)] Finas Malaysia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4464/pencapaian-filem-cereka-tempatan-di-peringkat-antarabangsa-1950-2017-finas-malaysia-764464.webp)

Pencapaian Filem Cereka Tempatan Di Peringkat Antarabangsa (1950-2017)] Finas Malaysia

[INISIATIF PEMBANGUNAN DATA INDUSTRI FILEM: PENCAPAIAN FILEM CEREKA TEMPATAN DI PERINGKAT ANTARABANGSA (1950-2017)] FINAS MALAYSIA INISIATIF PEMBANGUNAN DATA INDUSTRI FILEM: PENCAPAIAN FILEM CEREKA TEMPATAN DI PERINGKAT ANTARABANGSA (1950-2017) 1 KAJIAN & PENGUMPULAN DATA OLEH : Ahmad Syazli Muhd Khiar ([email protected]) Pengarah Dasar & Penyelidikan FINAS TARIKH KEMASKINI : 31 Disember 2017 (Tertakluk kepada kemaskini data dan maklumat dari masa ke semasa) Bil Judul Filem [INISIATIFPengarah PEMBANGUNANama N DATA INDUSTRINama Festival FILE M: PENCAPAIANTahun Tempat FILEM CEREKAPenerima TEMPATAN Status Pencapaian Produksi/Tahun DI PERINGKATPenyertaan ANTARABANGSA (1950-2017)] FINAS MALAYSIA Tayangan 1 Nasib B.S Rajhans Malay Film BFI Festival of 1950 London, UK Malay Film Tayangan Official Selection Productions/1949 Commonwealth Films Productions 2 Iman K.R.S Sastry Malay Film 1st Asia Pacific Film 1954 Tokyo, Malay Film Penyertaan Official Submission Productions/1954 Festival Jepun Productions 3 Hang Tuah Phani Majumdar Malay Film 3rd Asia Pacific Film 1956 Hong Kong Malay Film Penyertaan Official Submission Productions/1956 Festival Productions Tan Sri P. Ramlee Menang Penggubah Muzik Terbaik 7th Berlin International 1956 Berlin, Malay Film Pencalonan Filem Terbaik (Golden Bear) Film Festival Germany Production (In Competition) 4 Semerah Padi Tan Sri P. Ramlee Malay Film 3rd Asia Pacific Film 1956 Hong Kong Malay Film Penyertaan Official Submission Productions/1956 Festival Productions 5 Anakku Sazali Phani Majumdar Malay Film 4th Asia -

Singapore-Insider-2017-Q4 English

39604SIAG_PEC_Strategic_Global_148x210_SG Insider_Jul17_Inc.indd 1 19/7/17 11:01 AM HANDY TIPS 02 Useful information Farewell 2017 and about Singapore Hello 2018! WHAT’S ON 04 Exciting events in the months ahead ‘Tis the season to be jolly! Waste no more time and make the best of what you have left RETAIL THERAPY with 2017 – using our handy 20 guide, of course. Singapore’s shopping hotspots and what to When in Singapore, don't just buy from there eat; be a foodie and treat your taste buds to flavourful local cuisines. For starters, check out Newton Circus Food Centre COVER STORY or Ayer Rajah Food Centre, 11 as recommended by local chef Artist Dyn shares his Haikal Johari. Creatures of the favourite hawker centres in Singapore night can hit the city’s coolest bars such as Native and Ah Sam DAY TRIPPER Cold Drink Stall to enjoy local- 12 These brilliantly curated inspired tipples. THE EAT LIST tours will show you 24 Hawker highlights and Shopaholics, take your shopping different sides of Singapore the hottest tables in town to the next level by being a keeper of local artisanal BY NIGHT goods. For retail therapy with 28 Cool bars and clubs to a distinctly local spin, flip to our drink and be merry favourite section of the guide, Take Me Home (page 22 & 23), where you’ll find hip local gems. Want a fun day out with the little ones? Explore a different side of Singapore with your kids through various day tours or visit unique spots on our ESSENTIAL island such as The Live Turtle 14 SINGAPORE and Tortoise Museum, and The City must-dos and FAMILY FUN Karting Arena. -

Hong Leong Bank Berhad

December 17, 2019 Global Markets Research Fixed Income Fixed Income Daily Market Snapshot UST US Treasuries Tenure Closing (%) Chg (bps) US Treasuries closed weak on Monday on a lack of any 2-yr UST 1.63 2 meaningful news besides the firm Markit PMI data releases. 5-yr UST 1.70 5 The pullback was seen as a response to last week’s news that 10-yr UST 1.87 5 both the US and China finally reached an agreement to sign-off 30-yr UST 2.29 3 Phase 1 of the trade pact. The curve shifted up with overall benchmark yields ending between 2-5bps higher. The UST 2Y MGS GII* shed 2bps at 1.63% whilst the much-watched 10Y spiked 5bps Closing at 1.87%. With the removal of a great degree of uncertainty Tenure Closing (%) Chg (bps) Chg (bps) (%) pertaining to the US-China trade Phase 1 for now, traders and 3-yr 3.02 -2 3.10 0 investors may now be focussing on other economic data that 5-yr 3.25 -3 3.29 0 include reports on industrial production and housing starts. 7-yr 3.41 1 3.39 0 10-yr 3.44 0 3.55 0 MGS/GIIl 15-yr 3.68 -3 3.78 0 20-yr 3.74 -3 3.90 1 Local govvies saw low momentum last Monday as secondary 30-yr 4.11 0 4.00 0 market volume notched a mere RM1.49b with investor interest * Market indicative levels mainly in the off-the-run 20’s and benchmark 5Y MGS. -

Pdf My Metro

Sains Full paper Humanika The Homeless' Survival Strategy in Kuala Lumpur City Strategi Kelangsungan Hidup Gelandangan di Pusat Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur Syafiq Sham*, Doris Padmini Selvaratnam Fakulti Ekonomi dan Pengurusan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 UKM, Bangi Selangor, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Article history: Received: 1 November 2017 Received in revised form: 4 April 2018 Accepted: 16 April 2018 Published online: 30 April 2018 Abstract The objective of this study is to identify the source of income for the homeless and the ways they continue living in Pusat Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (KL). The data used are collected through interviews with 25 homeless people who were brought by the Welfare Department authority to the Program Latihan Khidmat Negara (PLKN) Geo Kosmo camp, Kuala Kubu Bharu, Selangor under the OPS Menyelamat and using the questionnaire on the 50 homeless people who came to Dapur Jalanan Kuala Lumpur (DJKL). Based on statistical result, 28 were self-employed, 3 were working in the private sector and 19 were unemployed while their total income (monthly) showed 11 people earning RM200 and below, RM201 to RM400 with 7 persons, RM401 to RM600 with 8 persons and RM601 or above only 5 people. Based on interviews conducted at the camp most of them did not have fixed income and jobs. The proposal based on the findings is to increase the role of the Social Welfare Department (JKM) and non-governmental organization (NGOs) in focusing on opening new job opportunities and improving skills to homeless people. Keywords: Sources of income for the homeless, homeless survival, Dapur Jalanan Kuala Lumpur, PLKN Geo Kosmo camp Abstrak Objektif kajian ini adalah untuk mengenalpasti sumber pendapatan dan cara-cara mereka meneruskan kehidupan di Pusat Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (KL). -

Chapter 1 Introduction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universiti Teknologi Malaysia Institutional Repository CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION This research focuses on the relationship between cultural tourism, cultural heritage management and tourism carrying capacity. The location of study area is Historical City of Melaka that has many cultural tourism values. This research will also discuss the impact and influence caused by the increasing number of visitors on cultural heritage management. 1.1 Background Currently, cultural tourism is a trend which grows along with heritage tourism. Cultural tourism is focused on improving the historical attraction. Cultural tourism is one of the primary economic assets. Cultural tourism will be used as tourism attraction to increase the number of visitors. Cultural tourism uses the cultural or heritage assets to destination tourism. Besides, cultural heritage is a potential asset to improve tourism development. Cultural heritage has to be preserved and protected because it has the potential to attract tourists and promote the country’s tourist destinations. Therefore, the tourism asset needs policies or guidelines to integrate cultural tourism and cultural heritage management, by preservation and conservation. Furthermore, it requires policies and guideline to improve the tourism development. Besides that, policies are needed to conduct conservation, preservation or renovation of the cultural heritage asset in order to maintain its historical and aesthetic values. In order to attract more visitors to a particular destination, the destination concerned should consider the following; good access, interesting and attractive attraction, modern facilities and wide ranging amenities. On the other hand, the negative impact will usually surface when the number of visitor exceeds the threshold limit combined with poor management. -

Teater Eksperimental Melayu: Satu Kajian Bentuk Dan Struktur Teks Dramatik

TEATER EKSPERIMENTAL MELAYU: SATU KAJIAN BENTUK DAN STRUKTUR TEKS DRAMATIK FAZILAH HUSIN UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA 2007 TEATER EKSPERIMENTAL MELAYU: SATU KAJIAN BENTUK DAN STRUKTUR TEKS DRAMATIK oleh FAZILAH HUSIN Tesis yang diserahkan untuk memenuhi keperluan bagi Ijazah Doktor Falsafah Drama dan Teater Oktober 2007 PENGHARGAAN Penghargaan tidak terhingga diberikan kepada penyelia utama, yang sentiasa memberikan tunjuk ajar, semangat, keyakinan, dan sokongan, Profesor Mohamed Ghouse Nasuruddin; ribuan terima kasih kepada Allahyarham Dr. Jamaludin Osman, semoga roh beliau dicucuri rahmat; majikan, Universiti Putra Malaysia yang memberi peluang; kakitangan Pusat Pengajian Seni, Universiti Sains Malaysia, atas segala bantuan dan kerjasama; suami, Murad Jailani dan anak-anak, Luqman Hakim, Balqish Iman, dan Sara Zunaira yang berkorban rasa dan masa; emak, Timah Haji Zali dan aruah apak, Husin bin Ngah; kakak, abang, dan keluarga yang mendoakan; serta rakan-rakan seperjuangan yang sentiasa mencabar. Hanya Allah subhanahu wa taala jua yang dapat membalas segala budi baik kalian. 711019065448 P-SED0007 ii SUSUNAN KANDUNGAN Muka surat PENGHARGAAN ii JADUAL KANDUNGAN iii SENARAI JADUAL vii SENARAI LAMPIRAN viii SENARAI PENERBITAN DAN SEMINAR ix ABSTRAK x ABSTRACT xii BAB SATU: LATAR BELAKANG KAJIAN 1.0 Pendahuluan 1 1.1 Permasalahan Kajian 2 1.2 Tujuan Kajian 6 1.3 Tumpuan dan Batasan Kajian 7 1.4 Sumber Data dan Asas Pemilihan Teks 8 1.5 Kepentingan Kajian 8 1.6 Definsi Konsep 11 1.6.1 Teater Eksperimental 11 1.6.2 Teater Eksperimental Melayu -

WASHINGTON 8 TAR Section

Five to One—or more Th... preponderant* of Circulalion-more thin Section One (lie combined circulation of any live oilier new*, papen In Warren County and vicinity, makti Tha Pages 1 to 8 Sl«f'» idverlJiinn ratei proportionally very low HE "WASHINGTON 8 TAR 52d YEAR— NUMEK :!1 WASHINGTON, WAUKEN COUNTY, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY M. 1(119 SUBSCRIPTION: $2.00 A YEAR E ASK BIDS TOR STREET WORK ,11™ ,T" BENSON'S A DIFFERENT UNION PICNIC WAS SUCCESS TO BUILD BUnZVILLE- "—:£=»• TREATY TOIL S. 5E1TEJ!" "i ""=•»" KIND OF GARNML " jnynlili' Affair a. l-'r,-)\ SOLDIER JOYS TODAY r,,!i,v.viiiK HI. .•i|,i,r,,v,,i ,,r a,.. .-• in n.riy lilt:.. N.-.-I|!,1;,1 in l:..|- i-iilliuw I.y .h" Slim- IHuliu'iiy.CmimilH- Pledges Help in Case of German «!;!i'lni;i"VXirS''u,!"nl'!'p'i;.u?'iHe Believes That the Public lil-tHVtll- l.llll,-,,,,, ,,,,.1 IT.-»l,5l.ri,,n _ _ „, Dinner and Parade Are Features Ml",,. l:..i |;l, I'M, lli.hi, I,:,:. ,.-tr.| l.i.ls f..i- 11,,. iv:.iirrii,•!„;.- ,..' Ka.xl :u,,l Invasion. <>:,t,.r,.,l >„ th" l.< si 1,-a.i'. in t.iu'ii. Must Be Pleased. Kiiiuiiiy .',-i,...i!s h.iii ., i !,.•!,IHI .HI: 11-reeholders Announce the Plans of the Day. 1 will I,,' n-,.i'iv<..l Mi.n.l.iy. An;.'. IN :ni,l <•.-. ,,,.. l,i..|,tl..ii"l, I.,it II,.I, til' TiS-r..''w,,.,'tt.%.''!V;i^"a,,,>.'.': ;i t"n.li'!;';| PointThatWay. WHITE TOWNSHJPrJOINS TOWN BAN ON ROUGH STUFF !§S lI ''iilI EASYGHAIBSFORTHE JURORS ' in "lUiitir mi- ' In ',-li:,rs.-l «;, .,,„, 1 .,( |-,-.,l IM,I. -

9-REF (VOLUME).Pdf

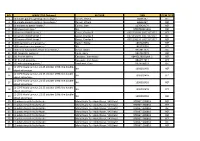

NO. MAIN TITLE (Volume) AUTHOR ISBN ITEM TYPE 1 10 minute guide to getting into college / Turner, O'Neal 28606167 REF 2 10 minute guide to getting into college / Turner, O'Neal 28606167 REF 3 10 minutes to better health / Collins, Jane 0276424174 REF 4 100 classic golf tips / NA 9780789315465 REF 5 100 years of Wall Street / Geisst, Charles R. 0071356193 | 0071373527 REF 6 100 years of Wall Street / Geisst, Charles R. 0071356193 | 0071373527 REF 7 100 years of Wall Street / Geisst, Charles R. 0071356193 | 0071373527 REF 8 1000 questions and answers / Baxter, Nicola 1843220091 REF 9 1000 questions and answers / NA 1843220091 REF 10 1000 su'al wa jawab fi al-Qur'an al-Karim / Ashur, Qasim 9953811075 REF 11 101 American customs : Collis, Harry 0844224073 REF 12 101 French idioms : Cassagne, Jean-Marie. 0844212903 (pbk.) : REF 13 101 French proverbs : Cassagne, Jean-Marie. 0844212911 REF 14 102 extra training games / Kroehnert, Gary 0074708023 REF 11 CEPSI Kuala Lumpur, 21-25 october 1996: the double- 15 NA 1000002459 REF edged advantage : 11 CEPSI Kuala Lumpur, 21-25 october 1996: the double- 16 NA 1000002459 REF edged advantage : 11 CEPSI Kuala Lumpur, 21-25 october 1996: the double- 17 NA 1000002459 REF edged advantage : 11 CEPSI Kuala Lumpur, 21-25 october 1996: the double- 18 NA 1000002459 REF edged advantage : 11 CEPSI Kuala Lumpur, 21-25 october 1996: the double- 19 NA 1000002459 REF edged advantage : 20 11 pidato terpilih Najib Razak : Mohd Najib Tun Abdul Razak, YAB Dato' 9789671288818 REF 21 11 pidato terpilih Najib Razak : Mohd