Reading Children's Book Editor Ursula Nordstrom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margaret Wise Brown and Bedtime Parody Sand

Lunar Perturbations – How Did We Get from Goodnight Moon to Go the F**k to Sleep?: Margaret Wise Brown and Bedtime Parody Sandy Hudock Colorado State University-Pueblo From an Audi commercial to celebrating the end of the second Bush presidency to the ghost of Mama Cass presiding over a dead Keith Moon, to the ubiquity of the iPad, Good Night Moon has been and no doubt will continue to be parodied or invoked for generations to come. Songwriters reference it, the television show The Wire gives an urban twist to its constant refrain of “good night-----“ with “good night, po-pos, good night hoppers, good night hustlers…” What makes this story so much a part of the collective consciousness, a veritable cultural meme? How did Margaret Wise Brown’s life and her influence in children's publishing result in the longstanding enchantment of Good Night Moon? Recent political and cultural parodies of the go to bed genre all ultimately hearken back to this one simple story painted in green and orange, and the intrinsic comfort it provides to children as a go to bed ritual. Born in New York in 1910 to a wealthy family, Brown was a middle child whose parents’ many moves within the Long Island area required that she change schools four times while growing up, including a stint at a Swiss boarding school. As a child, she made up stories (in her family, a polite way of saying she told lies) and then challenged her siblings to look up the answers in the multi-volume Book of Knowledge, for which she later penned two entries on writing for small children. -

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

The Kindergarten Canon: 100 Books Every Child Should Encounter By

The Kindergarten Canon Title Author 1 is One Tasha Tudor Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Judith Viorst & Ray Cruz Amazing Grace Mary Hoffman & Caroline Binch Anansi the Spider Gerald McDermott* Are You My Mother? P.D. Eastman Bear Called Paddington, A Michael Bond Bear Snores On Karma Wilson & Jane Chapman Beauty and the Beast, The Brothers Grimm* Big Red Barn, The Margaret Wise Brown & Felicia Bond Birthday for Frances, A Russell Hoban & Garth Williams Blueberries for Sal Robert McCloskey Bremen Town Musicians, The Brothers Grimm* Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? Bill Martin Jr. & Eric Carle Caps for Sale Esphyr Slobodkina Carrot Seed, The Ruth Krauss & Crockett Johnson Cars and Trucks and Things that Go Richard Scarry Cat in the Hat, The Dr. Seuss Chair for My Mother, A Vera B. Williams Bill Martin Jr. (author), John Archambault Chicka Chicka Boom Boom (author), and Lois Ehlert Chrysanthemum Kevin Henkes Cinderella Brothers Grimm* Click, Clack, Moo: Cows that Type Doreen Cronin & Betsy Lewin Corduroy Don Freeman Curious George Margret Rey and H. A. Rey Dear Zoo Rod Campbell Emperor's New Clothes, The Hans Christian Andersen* Fisherman and his Wife, The Brothers Grimm* Frederick Leo Lionni Freight Train Donald Crews Frog and Toad are Friends Arnold Lobel George and Martha James Marshall Gingerbread Man , The Fairy Tale* Giving Tree, The Shel Silverstein Go, Dog. Go! P.D. Eastman Goggles Ezra Jack Keats Goldilocks and the Three Bears Brothers Grimm* Good Night Gorilla Peggy Rathmann Good Night Moon Margaret Wise Brown & Clement Hurd Green Eggs and Ham Dr. -

Different Drummers

Special Issue: Different Drummers March/April 2013 Volume LXXXIX Number 2 ® Features Barbara Bader 21 Z Is for Elastic: The Amazing Stretch of Paul Zelinsky A look at the versatile artist’s career. Roger Sutton 30 Jack (and Jill) Be Nimble: An Interview with Mary Cash and Jason Low Independent publishers stay flexible and look to the future. Eugene Yelchin 41 The Price of Truth Reading books in a police state. Elizabeth Burns 47 Reading: It’s More Than Meets the Eye Making books accessible to print-disabled children. Columns Editorial Roger Sutton 7 See, It’s Not Just Me In which we celebrate the nonconforming among us. The Writer’s Page Polly Horvath and Jack Gantos 11 Two Writers Look at Weird Are they weird? What is weird, anyway? And will Jack ever reply to Polly? Different Drums What’s the strangest children’s book you’ve ever enjoyed? Elizabeth Bird 18 Seven Little Ones Instead Luann Toth 20 Word Girl Deborah Stevenson 29 Horrible and Beautiful Kristin Cashore 39 Embracing the Strange Susan Marston 46 New and Strange, Once Elizabeth Law 58 How Can a Fire Be Naughty? Christine Taylor-Butler 71 Something Wicked Mitali Perkins 72 Border Crossing Vaunda Micheaux Nelson 79 Wiggiling Sight Reading Leonard S. Marcus 54 Wit’s End: The Art of Tomi Ungerer A “willfully perverse and subversive individualist.” (continued on next page) March/April 2013 ® Columns (continued) Field Notes Elizabeth Bluemle 59 When Pigs Fly: The Improbable Dream of Bookselling in a Digital Age How one indie children’s bookstore stays SWIM HIGH ACROSS T H E SKY afloat. -

Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing As Critical Engagement in Writing Support

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2020 Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing as Critical Engagement in Writing Support Anna Cairney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Creative Writing Commons EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty in the department of ENGLISH of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by Anna Cairney Date Submitted: 1/27/2020 Date Approved: 1/27/2020 __________________________________ __________________________________ Anna Cairney Derek Owens, D.A. © Copyright by Anna Cairney 2020 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT Anna Cairney Editing is usually perceived in the pejorative within in the literature of composition studies generally, and specifically in writing center studies. Regardless if the Writing Center serves mostly undergraduates or graduates, the word “edit” has largely evolved to a narrow definition of copyediting or textual cleanup done by the author at the end of the writing process. Inversely, in trade publishing, editors and agents work with writers at multiple stages of production, providing editorial feedback in the form of reader’s reports and letters. Editing is a rich, intellectual skill of critically engaging with another’s text. What are the implications of differing literacies of editing for two fields dedicated to writing production? This dissertation examines the editorial practices of three leading 20th century editors: Maxwell Perkins, Katharine White, and Ursula Nordstrom. -

Updated Editions of Virginia Lee Burton's

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Fall 2009 Books for Children Use our 2 140 156 handy Harcourt Children’s Books Bill Peet: An Autobiography Holidays color-coded High-quality, award-winning key to determine books for more than eighty 141 158 each book’s years. Mariner Books Authors and Illustrators format. Check out the new adult titles by State, with Websites 19 from our highly acclaimed Clarion Books trade paperback line. 160 Picture Book As an adjective the word Awards & Accolades clarion means “brilliantly clear.” 142 An appropriate name Larousse Reference 161 for this distinctive imprint. The acclaimed line of bilingual Costumes and Website Board Book and foreign language dictionar - Resources 38 ies and books for children, for HMH Books more than 150 years. 162 Early Reader Fresh new formats and Index media tie-ins. 143 The American Heritage ® 167 Fiction 68 High School Dictionary Bookstore Representatives Houghton Mifflin The most comprehensive high Books for Children school dictionary available 168 A distinguished, award- today. Ordering Information Nonfiction winning publishing tradition. 144 101 Spring 2009 Backlist Paperback Sandpiper Paperbacks Imaginations soar with 153 our popular and classic Books by Publication Month Reference paperbacks. 154 Black History Month Cover 123 illustration Graphia Paperbacks © 2009 by Quality paperbacks for Jill McElmurry from today’s teen readers. Little Blue Truck Leads the Way by Alice Schertle Catalog design by Kat Black Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 222 Berkeley Street Boston, Massachusetts 02116 (617) -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Girls’ Guide to Power: Romancing the Cold War by Amanda Kirstin Allen A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Amanda Kirstin Allen Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Jo-Ann Wallace, English and Film Studies Patricia Demers, English and Film Studies Margaret Mackey, School of Library and Information Studies Cecily Devereux, English and Film Studies Michelle Meagher, Women’s Studies Beverly Lyon Clark, English, Wheaton College Dedicated to Mary Stolz and Ursula Nordstrom. Abstract This dissertation uses a feminist cultural materialist approach that draws on the work of Pierre Bourdieu and Luce Irigaray to examine the neglected genre of postwar-Cold War American teen girl romance novels, which I call “female junior novels.” Written between 1942 and the late 1960s by authors such as Betty Cavanna, Maureen Daly, Anne Emery, Rosamond du Jardin, and Mary Stolz, these texts create a kind of hieroglyphic world, where possession of the right dress or the proper seat in the malt shop determines a girl’s place within an entrenched adolescent social hierarchy. -

THESIS ARTISTS' BOOKS and CHILDREN's BOOKS Elizabeth A

THESIS ARTISTS’ BOOKS AND CHILDREN’S BOOKS Elizabeth A. Curren Art and the Book In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Art and the Book Corcoran College of Art + Design Washington, DC Spring 2013 © 2013 Elizabeth Ann Curren All Rights Reserved CORCORAN COLLEGE OF ART + DESIGN May 6, 2013 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY ELIZABETH A. CURREN ENTITLED ARTISTS’ BOOKS AND CHILDREN’S BOOKS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING, IN PART, REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTs IN ART AND THE BOOK. Graduate Thesis Committee: (Signature of Student) Elizabeth A. Curren (Printed Name of Student) (Signature of Thesis Reader) Georgia Deal (Printed Name of Thesis Reader) (Signature of Thesis Reader) Sarah Noreen Hurtt (Printed Name of Thesis Reader) (Signature of Program Chair and Advisor) Kerry McAleer-Keeler (Printed Name of Program Director and Advisor) Acknowledgements Many people have given generously of their time, their experience and their insights to guide me through this thesis; I am extremely grateful to all of them. The faculty of the Art and The Book Program at the Corcoran College of Art + Design have been most encouraging: Kerry McAleer-Keeler, Director, and Professors Georgia Deal, Sarah Noreen Hurtt, Antje Kharchi, Dennis O’Neil and Casey Smith. Students of the Corcoran’s Art and the Book program have come to the rescue many times. Many librarians gave me advice and suggestions. Mark Dimunation, Daniel DiSimone and Eric Frazier of the Rare Books and Special Collections at the Library of Congress have provided research support and valuable comments during the best internship opportunity anyone can ever have. -

Clement Hurd Drawings 1955, 1958BASC 11

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wm1mgw No online items Finding Aid to the Clement Hurd Drawings 1955, 1958BASC 11 Finding aid prepared by Susanne Mari Sakai Book Arts & Special Collections February 2020 100 Larkin Street San Francisco 94102 [email protected] URL: http://sfpl.org/index.php?pg=0200000201 Finding Aid to the Clement Hurd BASC 11 1 Drawings 1955, 1958BASC 11 Title: Clement Hurd Drawings Date: 1955, 1958 Identifier/Call Number: BASC 11 Creator: Hurd, Clement, 1908-1988 Physical Description: 1 flat file, 1 oversize flat box(2 linear feet) Contributing Institution: Book Arts & Special Collections Abstract: The collection contains original artwork by Clement Hurd for the children's books The Cat from Telegraph Hill and The Faraway Christmas: A Story of the Farallon Islands, both written by his wife Edith Thacher Hurd and published in the 1950's. Collection is stored on site. Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research and is available for use during Book Arts & Special Collections hours. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the San Francisco Public Library. All requests for permission to publish or quote from materials must be submitted in writing to Book Arts & Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the San Francisco Public Library as the owner of the physical items. Preferred Citation [Identification of item/Title of folder], Clement Hurd Drawings (BASC 11), Book Arts & Special Collections, San Francisco Public Library. Provenance Transferred from the San Francisco Public Library's Children's Department in or after 1993. -

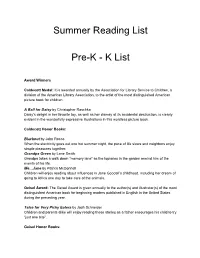

Summer Reading List Prek K List

Summer Reading List PreK K List Award Winners Caldecott Medal: It is awarded annually by the Association for Library Service to Children, a division of the American Library Association, to the artist of the most distinguished American picture book for children. A Ball for Daisy by Christopher Raschka Daisy’s delight in her favorite toy, as well as her dismay at its accidental destruction, is clearly evident in the wonderfully expressive illustrations in this wordless picture book. Caldecott Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco When the electricity goes out one hot summer night, the pace of life slows and neighbors enjoy simple pleasures together. Grandpa Green by Lane Smith Grandpa takes a walk down “memory lane” as the topiaries in the garden remind him of the events of his life. Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell Children will enjoy reading about influences in Jane Goodall’s childhood, including her dream of going to Africa one day to take care of the animals. Geisel Award: The Geisel Award is given annually to the author(s) and illustrator(s) of the most distinguished American book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year. Tales for Very Picky Eaters by Josh Schneider Children and parents alike will enjoy reading these stories as a father encourages his child to try “just one bite”. Geisel Honor Books: I Broke My Trunk! by Mo Willems Beloved characters, Elephant and Piggie, are at it again in this unlikely story of how poor Gerald broke his trunk. See Me Run by Paul Meisel A dog has a funfilled day at the dog park in this easytoread story. -

Barrington Bunny: Case of the Curious Clouds a Narrative Picture Book for Symbolic Play and STEM Curriculum

Bank Street College of Education Educate Graduate Student Independent Studies Spring 4-23-2020 Barrington Bunny: case of the curious clouds a narrative picture book for symbolic play and STEM curriculum Claudia Chung Bank Street College of Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/independent-studies Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Chung, C. (2020). Barrington Bunny: case of the curious clouds a narrative picture book for symbolic play and STEM curriculum. New York : Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/independent-studies/253 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Independent Studies by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Barrington Bunny: Case of the Curious Clouds A Narrative Picture Book for Symbolic Play And STEM Curriculum By Claudia Chung Early Childhood and Childhood General Education Faculty Mentor: Stan Chu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Science in Education Bank Street Graduate School of Education 2020 2 “I believe that at five we reach a point not to be achieved again and from whichever, after we at best keep and most often go down from. And so at 2 and 13, at 20 & 30 & 21 & 18 — each year has the newness of its own awareness to one alive. Alive- and life. “ — Margaret Wise Brown 3 Abstract Adults constantly use their imagination to help them visualize, problem-solve, enjoy a book, empathize, and think creatively.