Creating Children's Books Symposium Friday, October 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caldecott Medal Winners

C A L D E C O T T 1951 The Egg Tree by Katherine Milhous 1943 The Little House by Virginia Lee Burton M EDAL 1942 Make Way for Ducklings by Robert INNERS 1950 Song of the Swallows by Leo Politi W McCloskey 1949 The Big Snow by Berta and Elmer Hader 1941 They Were Strong and Good by Robert Law- son The Caldecott Medal is awarded annually by the Association of Library Service to Children, a divi- 1948 White Snow, Bright Snow by Alvin Tres- 1940 Abraham Lincoln by Ingri Parin D’Aulaire sion of the American Library Association, to the illustrator of the most distinguished American pic- selt, ill by Roger Duvoisin 1939 Mei Li by Thomas Handforth ture book for children. The medal honors Randolph Caldecott, a famous English illustrator of children’s 1938 Animals of the Bible by Helen D. Fish, 1947 The Little Island by Golden MacDonald ill by Dorothy Lathrop 2011 A Sick Day for Amos McGee ill Erin Stead Ill by Leonard Weisgard 2010 The Lion and the Mouse by Jerry Pinkney 2009 The House in the Night by Susan Swanson 1946 Rooster Crows by Maud and Miska Peter- 2008 The Invention of Hugo Cabaret by Brian Sel- znik sham 2007 Flotsam by David Wiesner 2006 The Hello, Goodbye Window by Chris Raschka 2005 Kitten’s First Full Moon by Kevin Henkes 1945 Prayer for a Child by Rachel Field, 2004 The Man Who Walked between Two Towers by Mordicai Gerstein Ill by Elizabeth Orton Jones 2003 My Friend Rabbit by Eric Rohmann 2002 The Three Pigs by David Wiesner 2001 So You Want to Be President by Judith 1944 Many Moons by James Thruber, Ill by St.George 2000 Joseph Had A little Overcoat by Simms Tabak Louis Slobodkin 1999 Snowflake Bentley by Jacqueline Briggs Mar- tin 1998 Rapunzel by Paul O. -

Margaret Wise Brown and Bedtime Parody Sand

Lunar Perturbations – How Did We Get from Goodnight Moon to Go the F**k to Sleep?: Margaret Wise Brown and Bedtime Parody Sandy Hudock Colorado State University-Pueblo From an Audi commercial to celebrating the end of the second Bush presidency to the ghost of Mama Cass presiding over a dead Keith Moon, to the ubiquity of the iPad, Good Night Moon has been and no doubt will continue to be parodied or invoked for generations to come. Songwriters reference it, the television show The Wire gives an urban twist to its constant refrain of “good night-----“ with “good night, po-pos, good night hoppers, good night hustlers…” What makes this story so much a part of the collective consciousness, a veritable cultural meme? How did Margaret Wise Brown’s life and her influence in children's publishing result in the longstanding enchantment of Good Night Moon? Recent political and cultural parodies of the go to bed genre all ultimately hearken back to this one simple story painted in green and orange, and the intrinsic comfort it provides to children as a go to bed ritual. Born in New York in 1910 to a wealthy family, Brown was a middle child whose parents’ many moves within the Long Island area required that she change schools four times while growing up, including a stint at a Swiss boarding school. As a child, she made up stories (in her family, a polite way of saying she told lies) and then challenged her siblings to look up the answers in the multi-volume Book of Knowledge, for which she later penned two entries on writing for small children. -

(ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to Present

Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) Caldecott Medal & Honor Books, 1938 to present 2014 Medal Winner: Locomotive, written and illustrated by Brian Floca (Atheneum Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing) 2014 Honor Books: Journey, written and illustrated by Aaron Becker (Candlewick Press) Flora and the Flamingo, written and illustrated by Molly Idle (Chronicle Books) Mr. Wuffles! written and illustrated by David Wiesner (Clarion Books, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing) 2013 Medal Winner: This Is Not My Hat, written and illustrated by Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press) 2013 Honor Books: Creepy Carrots!, illustrated by Peter Brown, written by Aaron Reynolds (Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division) Extra Yarn, illustrated by Jon Klassen, written by Mac Barnett (Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers) Green, illustrated and written by Laura Vaccaro Seeger (Neal Porter Books, an imprint of Roaring Brook Press) One Cool Friend, illustrated by David Small, written by Toni Buzzeo (Dial Books for Young Readers, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group) Sleep Like a Tiger, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski, written by Mary Logue (Houghton Mifflin Books for Children, an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company) 2012 Medal Winner: A Ball for Daisy by Chris Raschka (Schwartz & Wade Books, an imprint of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.) 2013 Honor Books: Blackout by John Rocco (Disney · Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group) Grandpa Green by Lane Smith (Roaring Brook Press, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership) Me...Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.) 2011 Medal Winner: A Sick Day for Amos McGee, illustrated by Erin E. -

Children's Literature

Children's Literature Handbooks Carpenter, H., & Prichard, M. (1984). The oxford companion to children's literature. Oxford Oxfordshire ; New York: Oxford University Press. Dictionary of literary biography. Detroit, Mich: Gale Research Co. v. 42: American writers for children before 1900 v. 52: American writers for children since 1960: fiction v. 62: American writers for children since 1960: poets, illustrators, and nonfiction authors v. 141: British children's wirters, 1880 - 1914 v. 160: British children's writers, 1914 - 1960 v. 161: British childrne's writers, since 1960 v. 163: British children's writers, 1800 - 1880 Fisher, M. T. (1975). Who's who in children's books. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Harris, L. L., Gale Research Company, & Gale Research Inc. Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism, , Irregular; Vol. 1. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (2002). Dictionary of american children's fiction, 1995-1999 : Books of recognized merit. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (1996). Dictionary of american children's fiction, 1990-1994 : Books of recognized merit. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (1993). Dictionary of american children's fiction, 1985-1989 : Books of recognized merit. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (1989). Dictionary of british children's fiction : Books of recognized merit. New York: Greenwood Press. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (1986). Dictionary of american children's fiction, 1960-1984 : Recent books of recognized merit. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Helbig, A., & Perkins, A. (1985). Dictionary of american children's fiction, 1859-1959 : Books of recognized merit. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Opie, I. A., & Opie, P. (1997). The oxford dictionary of nursery rhymes (New ed.). -

![Kenneth Bancroft Clark Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6892/kenneth-bancroft-clark-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-596892.webp)

Kenneth Bancroft Clark Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Kenneth Bancroft Clark Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Revised 2012 August Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998002 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm82078303 Prepared by Michael Spangler with the assistance of Janish Anderson, Sheila Day, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, Susie Moody, Thelma Todd, and Kathy Woodrell Revised and expanded by Kathleen O'Neill with the assistance of Sheralyn McCoy Collection Summary Title: Kenneth Bancroft Clark Papers Span Dates: 1897-2003 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1935-1990) ID No.: MSS78303 Creator: Clark, Kenneth Bancroft, 1914-2005 Extent: 173,750 items ; 496 containers plus 10 oversize ; 215 linear feet ; 1 microfilm reel Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Author, psychologist, and educator. Correspondence, memoranda, subject and project files, speeches and writings, transcripts of interviews and testimony, book drafts, minutes, reports, and administrative, academic, and financial records relating to Kenneth Bancroft Clark's career as a psychologist and professor at the City College, City University of New York, his contributions to the African-American civil rights movement and equal educational opportunities, and his various consulting firms, especially Metropolitan Applied Research Center, a group he organized in New York, N.Y., to advocate for the urban poor and disadvantaged. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

Hail to the Caldecott!

Children the journal of the Association for Library Service to Children Libraries & Volume 11 Number 1 Spring 2013 ISSN 1542-9806 Hail to the Caldecott! Interviews with Winners Selznick and Wiesner • Rare Historic Banquet Photos • Getting ‘The Call’ PERMIT NO. 4 NO. PERMIT Change Service Requested Service Change HANOVER, PA HANOVER, Chicago, Illinois 60611 Illinois Chicago, PAID 50 East Huron Street Huron East 50 U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. Association for Library Service to Children to Service Library for Association NONPROFIT ORG. NONPROFIT PENGUIN celebrates 75 YEARS of the CALDECOTT MEDAL! PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP PenguinClassroom.com PenguinClassroom PenguinClass Table Contents● ofVolume 11, Number 1 Spring 2013 Notes 50 Caldecott 2.0? Caldecott Titles in the Digital Age 3 Guest Editor’s Note Cen Campbell Julie Cummins 52 Beneath the Gold Foil Seal 6 President’s Message Meet the Caldecott-Winning Artists Online Carolyn S. Brodie Danika Brubaker Features Departments 9 The “Caldecott Effect” 41 Call for Referees The Powerful Impact of Those “Shiny Stickers” Vicky Smith 53 Author Guidelines 14 Who Was Randolph Caldecott? 54 ALSC News The Man Behind the Award 63 Index to Advertisers Leonard S. Marcus 64 The Last Word 18 Small Details, Huge Impact Bee Thorpe A Chat with Three-Time Caldecott Winner David Wiesner Sharon Verbeten 21 A “Felt” Thing An Editor’s-Eye View of the Caldecott Patricia Lee Gauch 29 Getting “The Call” Caldecott Winners Remember That Moment Nick Glass 35 Hugo Cabret, From Page to Screen An Interview with Brian Selznick Jennifer M. Brown 39 Caldecott Honored at Eric Carle Museum 40 Caldecott’s Lost Gravesite . -

A Never Ending Never Done Bibliography of Multicultural Literature for Younger and Older Children

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 388 SP 037 304 AUTHOR Walters, Toni S., Comp.; Cramer, Amy, Comp. TITLE A Never Ending Never Done Bibliography of Multicultural Literature for Younger and Older Children. First Edition. PUB DATE 96 NOTE 51p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; *American Indian Literature; American Indians; Asian Americans; *Black Literature; Blacks; Children; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethnic Groups; *Hispanic American Literature; Hispanic Americans; United States Literature IDENTIFIERS African Americans; *Asian American Literature; Latinos; *Multicultural Literature; Native Americans ABSTRACT People of all ages are addressed in this bibliography of multicultural literature. It focuses on four major ethnic groups: African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans, and Native Americans. Within each category a distinction is made between those works with an authentic voice and those with a realistic voice. An authentic voice is an author or illustrator who is from the particular ethnic group and brings expertise and life experience to his/her writings or illustrations. A realistic voice is that of an author or illustrator whose work is from outside that experience, but with valuable observations. An asterisk notes the distinction. No distinction is drawn between juvenile literature and adult literature. The decision is left to the reader to make the choices, because some adult literature may contain selections appropriate to children. Two appendices provide: a selected annotated bibliography (14 entries) on multiethnic/multicultural literature references and analyses and sources of multiethnic/multicultural books.(SPM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS April 3, 1990 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

6582 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 3, 1990 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TRIBUTES TO POLISH PRIME In both statements, the authors, each in his "establishing communism in Poland is like MINISTER MAZOWIECKI own way, offers an eloquent tribute to the trying to put a saddle on a cow." courage, vision, and leadership of Prime Min And it was finally and fully resurrected by HON. DAN ROSTENKOWSKI ister Mazowiecki, and to the great movement the roundtable agreement and the elections for political democracy and economic reform last year, in which the people of Poland, OF ILLINOIS given the first opportunity in fifty years to IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES which he symbolizes. freely and fairly determine their own desti I hope my colleagues will agree with me Tuesday, April 3, 1990 ny, threw out the communists and made that these statements should be made a part possible the establishment of the govern Mr. ROSTENKOWSKI. Mr. Speaker, we of the permanent record of this body. Accord ment led by the good and decent man we were recently given the high privilege of re ingly, I include the statements in their entirety honor by our presence here today-Prime ceiving the Honorable T adeusz Mazowiecki, at this point in the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD. Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki. the remarkable Prime Minister of the Republic ADDRESS BY REPRESENTATIVE STEPHEN J. So it seems to me that we have a very spe of Poland, on his first state visit to the United SOLARZ cial obligation to Prime Minister States. This is an extraordinary moment in the Mazowiecki, and to the Polish people, whose Over the course of his visit, Prime Minister history not only of our country but of the personal courage and political creativity Mazowiecki held many important meetings, in world. -

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

Caldecott Medal Winners

Hey, Al by Arthur Yorinks (1987) Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears by Caldecott Location: Picture Book Yorinks Verna Aardema (1976) Location: Picture Book Tales Why The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg Medal (1986) Arrow to the Sun by Gerald McDermott Location: Kids Holiday Christmas Van Allsburg (1975) Location: Picture Book Tales Arrow Winners Saint George and the Dragon by Marga- ret Hodges (1985) Duffy and the Devil by Harve Zemach Location: Kids 398.2342 Hodges (1974) The Randolph Caldecott Medal is awarded Location: Picture Book Tales Duffy Shadow by Blaise Cendrars annually by the Association for Library Service (1983) The Funny Little Woman by Arlene Mosel to Children to “the artist of the most distin- Location: Picture Book Tales (1973) guished American picture book for children.” Shadow Location: Picture Book Tales Funny One Fine Day by Nonny Hogrogian (1972) Jumanji by Chris Van Allsburg (1982) Location: Picture Book Hogrogian Location: Kids Illustrated Fiction Van Allsburg A Story A Story: An African Tale by Gail E. Fables by Arnold Lobel (1981) Haley (1971) Location: Picture Book Tales Collection Location: Picture Book Tales Story Ox-Cart Man by Donald Hall (1980) Sylvester and the Magic Pebble Location: Picture Book Hall by William Steig (1970) Location: Picture Book Steig The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses by Paul Goble (1979) Location: Picture Book Tales Girl Noah's Ark by Peter Spier (1978) Wilmington Memorial Library Location: Picture Book Spier 175 Middlesex Ave Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions by Wilmington, MA 01887 Margaret Musgrove (1977) wilmlibrary.org/kids Location: Kids 960 Musgrove Youth Services: 978-694-2098 Wolf in the Snow by Matthew The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Rapunzel by Paul O. -

![Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: a Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7632/annotated-bibliography-for-lower-elementary-reading-a-suggested-bibliography-for-students-grades-k-3-967632.webp)

Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: a Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 369 060 CS 011 678 AUTHOR Johnson, Lory, Comp.; And Others TITLE Annotated Bibliography for Lower Elementary [Reading]: A Suggested Bibliography for Students Grades K-3. INSTITUTION Iowa State Dept. of Education, Des Moines. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 74p.; For other bibliographies in this series, see CS 011 679-681. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Drama; Elementary School Students; Fiction; Folk Culture; Nonfiction; Poetry; Primary Education; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS Iowa ABSTRACT Designed to expose young readers to a wide variety of literary genres, this annotated bibliography provides a list of over 700 recently published children's literature selections representative of the universal themes in literature. Selections are divided into sections of folklore, drama, poetry, non-fiction, and fiction (the most extensive). The annotated bibliography is designed to assist teachers and students in improving the breadth and quality of reading in Iowa's lower elementary grades. Many of the titles in the annotated bibliography were published in the 1980s.(LS) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ANNOTATE D BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR LOW ER ELEMENTARY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Moe oi Educational -

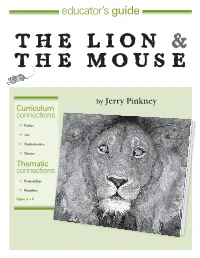

Educator's Guide

educator’s guide by Jerry Pinkney Curriculum connections D Fables D Art D Mathematics D Nature Thematic connections D Friendship D Families Ages 3 – 6 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS ActIVITIES 1. What is unusual about the front cover of this book? 1. Take a picture book safari. Ask your class to identify Ask your students to follow the lion’s gaze. What is and count all the different types of animals pictured he looking at? What could he be thinking about? in The Lion & the Mouse. Encourage your students to Flip to the back cover and ask the same questions search high and low, and not to forget the humans. about the mouse. 2. Make a room for a lion and mouse. How much space 2. The lion could have easily crushed the mouse when does each need? Measure the desks in your classroom. they first met. Instead, he lets go of the little creature. Are they big enough for a mouse? Measure your Why? classroom. Is it large enough for a lion? Measure the footprint of your school building. Could the king of 3. Two men set a trap for the lion. Why? What do your beasts have room enough to roam within it? students think they will do with him? 3. As a whole class project, research the natural habitat 4. Why does the mouse help the lion? of lions. Where do they live? What do they eat? How 5. Why does the mouse keep a rope knot? much can they weigh? In what ways do humans help lions? In what ways do they hurt them? 6.