Contagion, Stigmatization and Utopia As Therapy in Zhao Liang's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhang Yimou Interviews Edited by Frances Gateward

ZHANG YIMOU INTERVIEWS EDITED BY FRANCES GATEWARD Discussing Red Sorghum JIAO XIONGPING/1988 Winning Winning Credit for My Grandpa Could you discuss how you chose the novel for Red Sorghum? I didn't know Mo Yan; I first read his novel, Red Sorghum, really liked it, and then gave him a phone call. Mo Yan suggested that we meet once. It was April and I was still filming Old Well, but I rushed to Shandong-I was tanned very dark then and went just wearing tattered clothes. I entered the courtyard early in the morning and shouted at the top of my voice, "Mo Yan! Mo Yan!" A door on the second floor suddenly opened and a head peered out: "Zhang Yimou?" I was dark then, having just come back from living in the countryside; Mo Yan took one look at me and immediately liked me-people have told me that he said Yimou wasn't too bad, that I was just like the work unit leader in his village. I later found out that this is his highest standard for judging people-when he says someone isn't too bad, that someone is just like this village work unit leader. Mo Yan's fiction exudes a supernatural quality "cobblestones are ice-cold, the air reeks of blood, and my grandma's voice reverberates over the sorghum fields." How was I to film this? There was no way I could shoot empty scenes of the sorghum fields, right? I said to Mo Yan, we can't skip any steps, so why don't you and Chen Jianyu first write a literary script. -

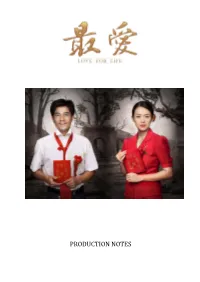

Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok

PRODUCTION NOTES Set in a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, LOVE FOR LIFE is the story of De Yi and Qin Qin, two victims faced with the grim reality of impending death, who unexpectedly fall in love and risk everything to pursue a last chance at happiness before it’s too late. SYNOPSIS In a small Chinese village where an illicit blood trade has spread AIDS to the community, the Zhao’s are a family caught in the middle. Qi Quan is the savvy elder son who first lured neighbors to give blood with promises of fast money while Grandpa, desperate to make amends for the damage caused by his family, turns the local school into a home where he can care for the sick. Among the patients is his second son De Yi, who confronts impending death with anger and recklessness. At the school, De Yi meets the beautiful Qin Qin, the new wife of his cousin and a recent victim of the virus. Emotionally deserted by their respective spouses, De Yi and Qin Qin are drawn to each other by the shared disappointment and fear of their fate. With nothing to look forward to, De Yi capriciously suggests becoming lovers but as they begin their secret affair, they are unprepared for the real love that grows between them. De Yi and Qin Qin’s dream of being together as man and wife, to love each other legitimately and freely, is jeopardized when the villagers discover their adultery. With their time slipping away, they must decide if they will surrender everything to pursue one chance at happiness before it’s too late. -

The Biopolitical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2018 The iopB olitical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds Xiaoyu Gao Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gao, Xiaoyu, "The iopoB litical Elements in Yan Lianke's Fiction Worlds" (2018). Masters Theses. 3619. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3619 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The GraduateSchool � EA'ill 11.'1I·��-- h l:'ll\'tll\11'\' Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate candidates Completing Theses in PartialFulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: •The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. •The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

China As Dystopia: Cultural Imaginings Through Translation Published In: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) Doi: 10.1080/1

China as dystopia: Cultural imaginings through translation Published in: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) doi: 10.1080/14781700.2015.1009937 Tong King Lee* School of Chinese, The University of Hong Kong *Email: [email protected] This article explores how China is represented in English translations of contemporary Chinese literature. It seeks to uncover the discourses at work in framing this literature for reception by an Anglophone readership, and to suggest how these discourses dovetail with meta-narratives on China circulating in the West. In addition to asking “what gets translated”, the article is interested in how Chinese authors and their works are positioned, marketed, and commodified in the West through the discursive material that surrounds a translated book. Drawing on English translations of works by Yan Lianke, Ma Jian, Chan Koonchung, Yu Hua, Su Tong, and Mo Yan, the article argues that literary translation is part of a wider programme of Anglophone textual practices that renders China an overdetermined sign pointing to a repressive, dystopic Other. The knowledge structures governing these textual practices circumscribe the ways in which China is imagined and articulated, thereby producing a discursive China. Keywords: translated Chinese literature; censorship; paratext; cultural politics; Yan Lianke Translated Literature, Global Circulations 1 In 2007, Yan Lianke (b.1958), a novelist who had garnered much critical attention in his native China but was relatively unknown in the Anglophone world, made his English debut with the novel Serve the People!, a translation by Julia Lovell of his Wei renmin fuwu (2005). The front cover of the book, published by London’s Constable,1 pictures two Chinese cadets in a kissing posture, against a white background with radiating red stripes. -

Restrictions on AIDS Activists in China

Human Rights Watch June 2005 Vol. 17, No. 5(C) Restrictions on AIDS Activists in China I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Case Study: The Closure of Orchid Orphanage ................................................................. 3 III. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology............................................................................................................................ 11 IV. Continuing Crackdown in Henan Province..................................................................... 12 Detention and harassment of Henan AIDS activists........................................................ 17 The mistreatment of activists helping AIDS orphans....................................................... 22 V. Harassment of Activists Working with Persons at High Risk of HIV Transmission................................................................................................................................ 29 Activists working with injection drug users and sex workers .......................................... 31 Restrictions on AIDS information for men who have sex with men............................. 36 Internet censorship................................................................................................................. 37 VI. Institutional Barriers to AIDS Organizations................................................................. -

People's Republic of China the Olympics Countdown – Repression of Activists Overshadows Death Penalty and Media Reforms

People’s Republic of China The Olympics countdown – repression of activists overshadows death penalty and media reforms Introduction "We must make efforts to create a harmonious society and a good social environment for successfully holding the 17th Communist Party Congress and the Beijing Olympic Games[…]We must strike hard at hostile forces at home and abroad, such as ethnic separatists, religious extremists, violent terrorists and ‘heretical organizations’ like the Falun Gong who carry out destabilizing activities." Zhou Yongkang, Minister of Public Security.(1) An overriding preoccupation with ensuring ‘harmony’ and ‘stability’ has featured heavily in China’s preparations for hosting major events including the Olympic Games in August 2008. As the statement above also illustrates, several senior Chinese officials appear to continue to equate such principles with a need to ‘strike hard’ against those perceived to be jeopardizing such an environment. While the statement refers to ‘violent terrorism’, it also includes groups or activists who may be engaged in peaceful activities, such as Falun Gong practitioners, ‘religious extremists’ or ‘ethnic separatists.’ Amnesty International remains deeply concerned that such ‘strike hard’ policies continue to be used to constrain the legitimate activities of a range of peaceful activists in China, including journalists, lawyers and human rights defenders. This report updates concerns in these areas, illustrated by the experiences of several individuals who have been detained or imprisoned in violation of their fundamental human rights. The failure of the Chinese authorities to address the legal and institutional weaknesses that allow such violations to flourish continues to hamper efforts to strengthen rule of law in China – a cornerstone for ‘harmony’ or ‘stability’ - and casts a deep shadow over other legal reforms which have been introduced over recent months. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema

Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema edited by Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre, 7 Tin Wan Praya Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2010 Hardcover ISBN 978-962-209-175-7 Paperback ISBN 978-962-209-176-4 All rights reserved. Copyright of extracts and photographs belongs to the original sources. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the copyright owners. Printed and bound by XXXXX, Hong Kong, China Contents List of Tables vii Acknowledgements ix List of Contributors xiii Introduction 1 Ying Zhu and Stanley Rosen Part 1 Film Industry: Local and Global Markets 15 1. The Evolution of Chinese Film as an Industry 17 Ying Zhu and Seio Nakajima 2. Chinese Cinema’s International Market 35 Stanley Rosen 3. American Films in China Prior to 1950 55 Zhiwei Xiao 4. Piracy and the DVD/VCD Market: Contradictions and Paradoxes 71 Shujen Wang Part 2 Film Politics: Genre and Reception 85 5. The Triumph of Cinema: Chinese Film Culture 87 from the 1960s to the 1980s Paul Clark vi Contents 6. The Martial Arts Film in Chinese Cinema: Historicism and the National 99 Stephen Teo 7. Chinese Animation Film: From Experimentation to Digitalization 111 John A. Lent and Ying Xu 8. Of Institutional Supervision and Individual Subjectivity: 127 The History and Current State of Chinese Documentary Yingjin Zhang Part 3 Film Art: Style and Authorship 143 9. -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

La Tua Terra, La Mia Lingua Traduzione Di Parte Del Romanzo Godersi La Vita Di Yan Lianke

Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Interpretariato e Traduzione Editoriale, Settoriale Tesi di Laurea La tua terra, la mia lingua Traduzione di parte del romanzo Godersi la vita di Yan Lianke Relatore Ch.ma Prof.ssa Nicoletta Pesaro Laureando Angela Ferri Matricola 988808 Anno Accademico 2016 / 2017 «Tutto può cambiare, ma non la lingua che ci portiamo dentro, anzi che ci contiene dentro di sé come un mondo più esclusivo e definitivo del ventre materno».1 1 Italo Calvino, cit. in Andrea Camilleri, Tullio De Mauro, La lingua batte dove il dente duole, Bari, Laterza, 2014, p. 71. I Abstract This thesis focuses on the translation into Italian of part of Yan Lianke’s Lenin’s Kisses. After an overall presentation of the topic of dialect translation in literature, the aim is to give a solution to the translation of the author’s Henan dialect by adopting a very informal language and by utilizing specific terms from a Southern Italian dialect. This thesis is divided into four sections. The first section can be considered as a long reflection on the importance of translating dialect in literature. The history of dialectal writing in China and the political attitudes toward it, are also part of this first chapter. Furthermore, this section illustrates how dialectal writing is linked to some authors’ love for their homeland. Yan Lianke and his novel are attentively presented in this section. The second section is the translation from Chinese into Italian of two chapters selected from the novel. Each chapter has a few features that are representative and reflects the unique structure of the entire novel. -

中国人的姓名 王海敏 Wang Hai Min

中国人的姓名 王海敏 Wang Hai min last name first name Haimin Wang 王海敏 Chinese People’s Names Two parts Last name First name 姚明 Yao Ming Last First name name Jackie Chan 成龙 cheng long Last First name name Bruce Lee 李小龙 li xiao long Last First name name The surname has roughly several origins as follows: 1. the creatures worshipped in remote antiquity . 龙long, 马ma, 牛niu, 羊yang, 2. ancient states’ names 赵zhao, 宋song, 秦qin, 吴wu, 周zhou 韩han,郑zheng, 陈chen 3. an ancient official titles 司马sima, 司徒situ 4. the profession. 陶tao,钱qian, 张zhang 5. the location and scene in residential places 江jiang,柳 liu 6.the rank or title of nobility 王wang,李li • Most are one-character surnames, but some are compound surname made up of two of more characters. • 3500Chinese surnames • 100 commonly used surnames • The three most common are 张zhang, 王wang and 李li What does my name mean? first name strong beautiful lively courageous pure gentle intelligent 1.A person has an infant name and an official one. 2.In the past,the given names were arranged in the order of the seniority in the family hierarchy. 3.It’s the Chinese people’s wish to give their children a name which sounds good and meaningful. Project:Search on-Line www.Mandarinintools.com/chinesename.html Find Chinese Names for yourself, your brother, sisters, mom and dad, or even your grandparents. Find meanings of these names. ----What is your name? 你叫什么名字? ni jiao shen me ming zi? ------ 我叫王海敏 wo jiao Wang Hai min ------ What is your last name? 你姓什么? ni xing shen me? (你贵姓?)ni gui xing? ------ 我姓 王,王海敏。 wo xing wang, Wang Hai min ----- What is your nationality? 你是哪国人? ni shi na guo ren? ----- I am chinese/American 我是中国人/美国人 Wo shi zhong guo ren/mei guo ren 百家 姓 bai jia xing 赵(zhào) 钱(qián) 孙(sūn) 李(lǐ) 周(zhōu) 吴(wú) 郑(zhèng) 王(wán 冯(féng) 陈(chén) 褚(chǔ) 卫(wèi) 蒋(jiǎng) 沈(shěn) 韩(hán) 杨(yáng) 朱(zhū) 秦(qín) 尤(yóu) 许(xǔ) 何(hé) 吕(lǚ) 施(shī) 张(zhāng).