Impressionism: Reflections and Perceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In a Splendid Exhibition, the École Des Beaux- Arts in Paris Is Currently

Ausstellungsbericht 22.12.2008 Exhibition Review Editor: R. Donandt Exhibition: Figures du corps. Une leçon d'anatomie aux beaux-arts. Paris, École natio- nale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris. 21.10.2008-04.01.2009 Exhibition catalogue: Philippe Comar (ed.): Figures du corps. Une leçon d'anatomie aux beaux-arts. Beaux-arts de Paris les editions, 2008. 509 p., 800 ill. ISBN: 978-2-84056-269- 6. 45,- EUR. Mechthild Fend, University College London In a splendid exhibition, the École des beaux- sixteenth-century displays include the well arts in Paris is currently showing their own known anatomical treatises by Vesalius and anatomical collections enriched by a small Estienne, studies on proportion after Vitruvius number of objects from other French institu- and by Lomazzo and Dürer, as well as écorchés tions. Usually behind the scenes - stored away and muscle studies by Bandinelli or Antonio del in archives and galleries reserved for the train- Pollaiuolo. In the next of the six sections, which ing of art students - the books, prints, draw- are organized more or less in chronological or- ings, photographs, waxmodels or casts are der, the formation of the French art academy up now centre stage in two large exhibition halls until the early nineteenth century is addressed, at Quai Malaquais. With these materials the especially the increasing specialisation of anat- exhibition traces the history of anatomy train- omy training for artists; this development is also ing at the French national art school. The pres- explored in the catalogue essay by Morwena tigious institution was founded in 1648 under Joly. -

16 Exhibition on Screen

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern

Lauren Jimerson exhibition review of Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Lauren Jimerson, exhibition review of “Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern ,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw. 2020.19.1.14. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Jimerson: Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Toulouse-Lautrec: Resolutely Modern Grand Palais, Paris October 9, 2019–January 27, 2020 Catalogue: Stéphane Guégan ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: Résolument moderne. Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RMN–Grand Palais, 2019. 352 pp.; 350 color illus.; chronology; exhibition checklist; bibliography; index. $48.45 (hardcover) ISBN: 978–2711874033 “Faire vrai et non pas idéal,” wrote the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864– 1901) in a letter to his friend Étienne Devismes in 1881. [1] In reaction to the traditional establishment, constituted especially by the École des Beaux-Arts, the Paris Salon, and the styles and techniques they promulgated, Toulouse-Lautrec cultivated his own approach to painting, while also pioneering new methods in lithography and the art of the poster. He explored popular, even vulgar subject matter, while collaborating with vanguard artists, writers, and stars of Bohemian Paris. Despite his artistic innovations, he remains an enigmatic and somewhat liminal figure in the history of French modern art. -

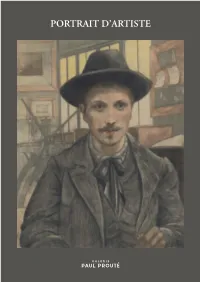

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

The Myth of the City in the French and the Georgian Symbolist Aesthetics

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention 5(03): 4519-4525, 2018 DOI: 10.18535/ijsshi/v5i3.07 ICV 2015: 45.28 ISSN: 2349-2031 © 2018, THEIJSSHI Research Article The Myth of the City in the French and the Georgian Symbolist Aesthetics Tatia Oboladze PhD student at Ivane Javakhisvhili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia,young-researcher at Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature ―Modern Art is a genuine offspring of the city… the city The cultural contexts of the two countries were also different. created new images, here the foundation was laid for the If in the 19th-c. French literature the tendencies of literary school, known as Symbolism…The poet’s Romanticism and Realism (with certain variations) co-existed consciousness was burdened by the gray iron city and it and it was distinguished by paradoxes, striving towards poured out into a new unknown song‖ (Tabidze 2011: 121- continuous formal novelties, the beginning of the 20th c. was 122), - writes Georgian Symbolist Titsian Tabidze in his the period of stagnation of Georgian culture. Although in the program article Tsisperi Qantsebit (With Blue Horns). Indeed, work of individual authors (A.Abasheli, S.Shanshiashvili, in the Symbolist aesthetics the city-megalopolis, as a micro G.Tabidze, and others) aesthetic features of modernism, model of the material world, is formed as one of the basic tendencies of new art were observable, on the whole, literature concepts. was predominated by epigonism1. Against this background, in Within the topic under study we discuss the work of Charles 1916, the first Symbolist literary group Tsisperi Qantsebi (The Baudelaire and the poets of the Georgian Symbolist school Blue Horns) came into being in the Georgian literary area. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Caroline Mc Corriston Claude Monet (1840-1926) ● Monet was the leading figure of the impressionist group. ● As a teenager in Normandy he was brought to paint outdoors by the talented painter Eugéne Boudin. Boudin taught him how to use oil paints. ● Monet was constantly in financial difficulty. His paintings were rejected by the Salon and critics attacked his work. ● Monet went to Paris in 1859. He befriended the artists Cézanne and Pissarro at the Academie Suisse. (an open studio were models were supplied to draw from and artists paid a small fee).He also met Courbet and Manet who both encouraged him. ● He studied briefly in the teaching studio of the academic history painter Charles Gleyre. Here he met Renoir and Sisley and painted with them near Barbizon. ● Every evening after leaving their studies, the students went to the Cafe Guerbois, where they met other young artists like Cezanne and Degas and engaged in lively discussions on art. ● Monet liked Japanese woodblock prints and was influenced by their strong colours. He built a Japanese bridge at his home in Giverny. Monet and Impressionism ● In the late 1860s Monet and Renoir painted together along the Seine at Argenteuil and established what became known as the Impressionist style. ● Monet valued spontaneity in painting and rejected the academic Salon painters’ strict formulae for shading, geometrically balanced compositions and linear perspective. ● Monet remained true to the impressionist style but went beyond its focus on plein air painting and in the 1890s began to finish most of his work in the studio. Personal Style and Technique ● Use of pure primary colours (straight from the tube) where possible ● Avoidance of black ● Addition of unexpected touches of primary colours to shadows ● Capturing the effect of sunlight ● Loose brushstrokes Subject Matter ● Monet painted simple outdoor scenes in the city, along the coast, on the banks of the Seine and in the countryside. -

Leonardo in Verrocchio's Workshop

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 32 Leonardo da Vinci: Pupil, Painter and Master National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press TB32 prelims exLP 10.8.indd 1 12/08/2011 14:40 This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2011 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including BRISTOL photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without © Photo The National Gallery, London / By Permission of Bristol City prior permission in writing from the publisher. Museum & Art Gallery: fig. 1, p. 79. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence © Galleria deg li Uffizi, Florence / The Bridgeman Art Library: fig. 29, First published in Great Britain in 2011 by p. 100; fig. 32, p. 102. © Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale National Gallery Company Limited Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street Culturali: fig. 1, p. 5; fig. 10, p. 11; fig. 13, p. 12; fig. 19, p. 14. © London WC2H 7HH Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Fiorentino, Gabinetto Fotografico, Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali / Photo Scala, www.nationalgallery. org.uk Florence: fig. 7, p. -

Artists at Play Natalia Erenburg, Iakov Tugendkhold, and the Exhibition of Russian Folk Art at the “Salon D’Automne” of 1913

Experiment 25 (2019) 328-345 brill.com/expt Artists at Play Natalia Erenburg, Iakov Tugendkhold, and the Exhibition of Russian Folk Art at the “Salon d’Automne” of 1913 Anna Winestein Executive Director, Ballets Russes Arts Initiative, and Associate, Davis Center at Harvard University and Center for the Study of Europe at Boston University [email protected] Abstract The exhibition of Russian folk art at the Paris “Salon d’Automne” of 1913 has been gen- erally overlooked in scholarship on folk art, overshadowed by the “All-Russian Kustar Exhibitions” and the Moscow avant-garde gallery shows of the same year. This article examines the contributions of its curator, Natalia Erenburg, and the project’s instiga- tor, Iakov Tugendkhold, who wrote the catalogue essay and headed the committee— both of whom were artists who became critics, historians, and collectors. The article elucidates the show’s rationale and selection of exhibits, the critical response to it and its legacy. It also discusses the artistic circles of Russian Paris in which the project origi- nated, particularly the Académie russe. Finally, it examines the project in the context of earlier efforts to present Russian folk art in Paris, and shows how it—and Russian folk art as a source and object of collecting and display—brought together artists, collec- tors, and scholars from the ranks of the Mir iskusstva [World of Art] group, as well as the younger avant-gardists, and allowed them to engage Parisian and European audi- ences with their own ideas and artworks. Keywords “Salon d’Automne” – Natalia Erenburg – Iakov Tugendkhold – Russian folk art – Paris – Mir iskusstva – Mikhail Larionov – Academie russe Overshadowed by both the “All-Russian Kustar Exhibitions” of 1902 and 1913 in St. -

1998 Education

1998 Education JANUARY JUNE 11 Video: Alfred Steiglitz: Photographer 2–5 Workshop: Drawing for the Doubtful, Earnest Ward, artist 17 Teacher Workshop: The Art of Making Books 3 Video: Masters of Illusion 18 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove’s Nature Abstraction, 10 Video: Cezanne: The Riddle of the Bathers Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 17 Video: Mondrian 25 Members Preview: O’Keeffe and Texas 21 Gallery Talk: Nature and Symbol: Impressionist and 26 Colloquium: The Making of the O’Keeffe and Texas Post-impressionism Prints from the McNay Collection, Exhibition, Sharyn Udall, Art Historian, William J. Chiego, Lyle Williams, Curator, Prints and Drawings Director, Rose M. Glennon, Curator of Education 22 Lecture and Members Preveiw: The Garden Setting: Nature Designed, Linda Hardberger, Curator of the Tobin FEBRUARY Collection of Theatre Arts 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 24 Teacher Workshop: Arts in Education, Getty 8 Video: Georgia O’Keeffe: The Plains on Paper Education Institute 12 Gallery Talk: Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe and American Nature, Charles C. Eldredge, title? JULY 15 Video: Alfred Stieglitz: Photographer 7 Members Preview: Kent Rush Retrospective 21 Symposium: O’Keeffe in Texas 12 Gallery Talk: A Discourse on the Non-discursive, Kent Rush, artist MARCH 18 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 1 Video: Women in Art: O’Keeffe 19 Performance: A Different Notion of Beautiful, Gemini Ink 8 Lunch and Lecture: A Photographic Affair: Stieglitz’s 26 Gallery Talk: Kent Rush Retrospective, Lyle Williams, Portraits -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson.