Aeschylean Structure and Text in New Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heracles : Myth Becoming

Natibnal Library Bibhotheque naticmale I* of Canada du Canada Canadian Theses Service Services des theses canadiennes Ottawa, Canada K1 A ON4 CANADIAN THESES THESES CANADIENNES NOTICE The quality of this microfiche is heavily dependent upon the La qualite de cette microfiche depend grandement de la qualite quality of the original thesis submitted fcr microfilming. Every de la these soumise au microfilmage. Nous avons tout fail pour effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduc- assurer uoe qualit6 superieure de reproduction. tion possible. D If pages are missing, contact the university which granted the S'il 'manque des pages, veuillez communiquer avec I'univer- degree. Some pages may have indistinct print especially if the original certatnes pages peut laisser A pages were typed with a poor typewriter ribbon or if the univer-- ont 6t6 dactylographi6es sity sent us an inferior photocopy. a I'aide d'un ruban us6 ou si Imuniversit6nous a fa;t parvenir une photocopie de qualit6 inf6rieure. Previously copyrighted materials (journal articles, published cuments qui font d6jA I'objet d'un droit d'auteur (articles tests, etc.) are not filmed. ue, examens publi&, etc.) ne sont pas microfilmes. Reproduction in full or in part of this film is governed by the La reproduction, mGme partielle, de ce microfilm est soumke Canadian Copyright Act, R.S.C. 1970, c. C-30. A la Loi canadienne sur le droit d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C-30. THIS DI~ERTATION LA THESE A ETE HAS BEEN iICROFILMED M~CROFILMEETELLE QUE EXACTLY AS RECEIVED NOUS L'AVONS REGUE THE HERACLES: MYTH BECOMING MAN. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

Nagy Commentary on Euripides, Herakles

Informal Commentary on Euripides, Herakles by Gregory Nagy 97 The idea of returning from Hades implies a return from death 109f The mourning swan... Cf. the theme of the swansong. Cf. 692ff. 113 “The phantom of a dream”: cf. skias onar in Pindar Pythian 8. 131f “their father’s spirit flashing from their eyes”: beautiful rendition! 145f Herakles’ hoped-for return from Hades is equated with a return from death, with resurrection; see 297, where this theme becomes even more overt; also 427ff. 150 Herakles as the aristos man: not that he is regularly described in this drama as the best of all humans, not only of the “Greeks” (also at 183, 209). See also the note on 1306. 160 The description of the bow as “a coward’s weapon” is relevant to the Odysseus theme in the Odyssey 203 sôzein to sôma ‘save the body’... This expression seems traditional: if so, it may support the argument of some linguists that sôma ‘body’ is derived from sôzô ‘save’. By metonymy, the process of saving may extend to the organism that is destined to be saved. 270 The use of kleos in the wording of the chorus seems to refer to the name of Herakles; similarly in the wording of Megara at 288 and 290. Compare the notes on 1334 and 1369. 297 See at 145f above. Cf. the theme of Herakles’ wrestling with Thanatos in Euripides Alcestis. 342ff Note the god-hero antagonism as expressed by Amphitryon. His claim that he was superior to Zeus in aretê brings out the meaning of ‘striving’ in aretê (as a nomen actionis derived from arnumai; cf. -

THE HERO and HIS MOTHERS in SENECA's Hercules Furens

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XXIII/1 • 2013 pp. 103–128. ISBN 978-83-7654-209-6. ISSN 0302-7384 Mateusz Stróżyński Instytut Filologii Klasycznej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza ul. Fredry 10, 61-701 Poznań Polska – Poland The Hero and His Mothers in Seneca’S Hercules FUreNs abstraCt. Stróżyński Mateusz, The hero and his mothers in Seneca’s Hercules Furens. The article deals with an image of the heroic self in Seneca’s Hercules as well as with maternal images (Alcmena, Juno and Megara), using psychoanalytic methodology involving identification of complementary self-object relationships. Hercules’ self seems to be construed mainly in an omnipotent, narcissistic fashion, whereas the three images of mothers reflect show the interaction between love and aggression in the play. Keywords: Seneca, Hercules, mother, psychoanalysis. Introduction Recently, Thalia Papadopoulou have observed that the critics writing about Seneca’s Hercules Furens are divided into two groups and that the division is quite similar to what can be seen in the scholarly reactions to Euripides’ Her- akles.1 However, the reader of Hercules Furens probably will not find much 1 See: T. Papadopoulou, Herakles and Hercules: The Hero’s ambivalence in euripides and seneca, “Mnemosyne” 57:3, 2004, pp. 257–283. The author reviews shortly the literature about the play and in the first group of critics, of those who are convinced that Hercules is “mad” from the beginning, but his madness gradually develops, she enumerates Galinsky (G.K. Galinsky, The Herakles Theme: The adaptations of the Hero in literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Oxford 1972), Zintzen (C. -

An Analysis of Heracles As a Tragic Hero in the Trachiniae and the Heracles

The Suffering Heracles: An Analysis of Heracles as a Tragic Hero in The Trachiniae and the Heracles by Daniel Rom Thesis presented for the Master’s Degree in Ancient Cultures in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Annemaré Kotzé March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis is an examination of the portrayals of the Ancient Greek mythological hero Heracles in two fifth century BCE tragic plays: The Trachiniae by Sophocles, and the Heracles by Euripides. Based on existing research that was examined, this thesis echoes the claim made by several sources that there is a conceptual link between both these plays in terms of how they treat Heracles as a character on stage. Fundamentally, this claim is that these two plays portray Heracles as a suffering, tragic figure in a way that other theatre portrayals of him up until the fifth century BCE had failed to do in such a notable manner. This thesis links this claim with a another point raised in modern scholarship: specifically, that Heracles‟ character and development as a mythical hero in the Ancient Greek world had given him a distinct position as a demi-god, and this in turn affected how he was approached as a character on stage. -

How Disney's Hercules Fails to Go the Distance

Article Balancing Gender and Power: How Disney’s Hercules Fails to Go the Distance Cassandra Primo Departments of Business and Sociology, McDaniel College, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] Received: 26 September 2018; Accepted: 14 November; Published: 16 November 2018 Abstract: Disney’s Hercules (1997) includes multiple examples of gender tropes throughout the film that provide a hodgepodge of portrayals of traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. Hercules’ phenomenal strength and idealized masculine body, coupled with his decision to relinquish power at the end of the film, may have resulted in a character lacking resonance because of a hybridization of stereotypically male and female traits. The film pivots from hypermasculinity to a noncohesive male identity that valorizes the traditionally-feminine trait of selflessness. This incongruous mixture of traits that comprise masculinity and femininity conflicts with stereotypical gender traits that characterize most Disney princes and princesses. As a result of the mixed messages pertaining to gender, Hercules does not appear to have spurred more progressive portrayals of masculinity in subsequent Disney movies, showing the complexity underlying gender stereotypes. Keywords: gender stereotypes; sexuality; heroism; hypermasculinity; selflessness; Hercules; Zeus; Megara 1. Introduction Disney’s influence in children’s entertainment has resulted in the scrutiny of gender stereotypes in its films (Do Rozario 2004; Dundes et al. 2018; England et al. 2011; Giroux and Pollock 2010). Disney’s Hercules (1997), however, has been largely overlooked in academic literature exploring the evolution of gender portrayals by the media giant. The animated film is a modernization of the classic myth in which the eponymous hero is a physically intimidating protagonist that epitomizes manhood. -

Bacchylides Ode5

Bacchylides Ode5 - Begins with praising Hieron of Syracuse (Muses give him gifts) & his horse Pherenicos (won Olympic races) by servant ourania (a muse too, who is gold-banded) by is cut off by Zeus eagle. - Hercules also known as ruiner of the gates (held the bold hearted shaker of the spear)and goes to underworld to slay Cerberos - Meleagros is supposedly guarded by his mom althaia so he can live for long - It later talks about Hercules who descended to the realm of death while performing his labors and encounters meleagros whos sister Hercules takes and marries ->Deianeira , whose hands he is destined to die Heracles - Zeus made the nights long till 3 looked like Amphitryon to sleep with Alcmene -> 2 sons -> Hercales to zeus and Iphicles to Amphitryon. - When heracules was born Hera sent two giants serpents to kill him. But Hercules killed them. - Some say Amphitryon did it to see who is real son was, and Iphicles fled, thats how he found out it was his. - Heracles teachers include: Autolycos (wrestle), Eurytos (bow), Castor (armor) After the Labors - Hercules gave back Megara to Iolaos - He joined a prized game with Eurytos, and when heracules won, he went back on his word of giving Iole to Heracules who they feared would kill the kids - After this, some cattle got stolen and Eurytos thought it was Heracules. Eurytos son Iphitos didn’t believe it and went to see Heracules who went crazy and killed him. And he felt sorry so tried to get purified and caught a deadly disease (from HIppolytos while cleanse) - He tried to steal the tripod to get the oracle to cure his disease FROM a temple, APOLLO fought Heracules, Zeus send a thunderbolt to separate them. -

Euripides' Heracles

Euripides’ Heracles – A Hero Denied a Family. Heracles (Hercules) was one of the most famous of all Greek heroes. The mortal son of Zeus, he was renowned for completing twelve incredible labors involving taking wild beasts and visiting the ends of the earth. In this play, Heracles has been away from home for a year trying to complete his final labor - an impossible journey to the underworld where only the dead may go. His wife, Megara, his step-father, Amphityron, and his children wait for his return and fear the worst – that he has perished and will never return. In the meantime, there has been a violent coup and the king, the father of Megara and benefactor of Heracles, has been overthrown and killed by a man called Lycus, who feels he has a right to the throne. Lycus is a man of the people – a soldier who despises the aristocrats who have been in power. He places Heracles’ family under a death sentence and tells them that they must all die, including the children so the line of the king will be extinguished. Megara asks for a little more time to prepare her children for their deaths and Heracles appears just in time, having secretly made his way into the city. He learns of what Lycus intends to do to his family and plans to stop him. His father urges him to hide inside the house. When Lycus arrives, Amphitryon asks him inside and we know he is going to meet his death at the hands of Heracles. But the goddess Hera sends the spirit of Madness on Heracles. -

Metadrama and Movement of Plot in Seneca's Hercules Furens

144 STAVROS FRANGOULIDIS From Victor to Victim: Metadrama and Movement of Plot in Seneca’s Hercules Furens STAVROS FRANGOULIDIS Aristotle University of Thessaloniki [email protected] Seneca’s Hercules Furens dramatizes Juno’s success in transforming Hercules into a criminal. This is set in direct contrast to her failed attempts in the dramatic past to bring about his demise, which only served to boost his renown as a benefactor of mankind. She achieves her success despite the existence of a competing authorial plan. Juno is bent on turning her stepson against his divine father and leading him to slaughter his family, so as to prevent him from attaining godhood; for his part, Hercules plans to implement his vision of a new Golden Age and gain immortality by styling himself as eradicator of evils1. When the two plans collide, Hercules is unable to figure out the true meaning of events: 1 — The text of Seneca’s Hercules Furens is from the Loeb edition by Fitch 2002. All English translations of Seneca’s text are from the Chicago University works of Seneca in translation by Konstan 2017. I would like to thank David Konstan, Stephanie Winder, and Niki Ikonomaki for thoughtful comments on various stages in the development of this essay. I am also grateful to EuGestA’s editor Jacqueline Serris, the editorial assistant Florence Verecque and the three anonymous referees whose detailed comments improved the paper considerably. The remaining flaws are my own. On Hercules’ vision of a new Golden Age, see Fitch 1987, 361; also Papadopoulou 2004, 270. EuGeStA - n°10 - 2020 FROM VICTOR TO VICTIM 145 he believes himself to be eliminating the remaining harm in the world, whereas in reality he is acting as Juno’s agent, directing his assault against heaven and exterminating his own domus. -

Body Paragraph #1 – Exemplar 1 the Walt Disney Animated Movie

Body Paragraph #1 – Exemplar 1 Topic Sentence The Walt Disney animated movie Hercules is based on the most famous hero of The main idea being ancient Greek mythology. Both the movie and the original myth differ in quite a few discussed in body ways. The movie version deviates, not only in the story of Hercules himself, but also in paragraph #1 of your essay is: The Disney details that pertain to many other aspects of classical mythology. version of Hercules differs greatly from the original Greek One of the biggest differences between the two versions of Hercules was that Hera myth. drove Hercules crazy and was not his real mother in the myth, but Disney portrayed her This is the main idea of the paragraph and as Hercules’s real mother, the wife to Zeus and they lived as a happy family. In the real must be clearly stated myth Hercules’s father Zeus was with many different women, including Alcmene who in the TOPIC SENTENCE is Hercules’s mother, this made Hera very mad. Hera decided to take her anger out on Hercules by driving him mad. This eventually led to him killing his wife and children, which is the reason he has to complete 12 labors. In the Disney movie Zeus and Hera are happily married with their son Hercules, Hera is not the enemy whatsoever. As Evidence to punishment for murdering his wife and children Hercules had 12 labors to complete in Support The bulk of this the myth. These were daunting tasks that some deemed impossible, including killing paragraph consists of Hydra, the 9 headed serpent snake and the Nemean lion, along with cleaning manure points and arguments supported by filled stables and capturing Cerberus, the 3 headed watch dog of the Underworld. -

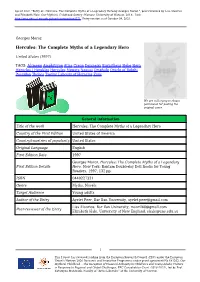

OMC | Data Export

Ayelet Peer, "Entry on: Hercules: The Complete Myths of a Legendary Hero by Georges Moroz ", peer-reviewed by Lisa Maurice and Elizabeth Hale. Our Mythical Childhood Survey (Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2018). Link: http://omc.obta.al.uw.edu.pl/myth-survey/item/271. Entry version as of October 04, 2021. Georges Moroz Hercules: The Complete Myths of a Legendary Hero United States (1997) TAGS: Alcmene Amphitryon Atlas Creon Deianeira Eurystheus Hebe Hera Heracles / Herakles Hercules Megara Nessus Omphale Oracle of Delphi Poseidon Thebes Twelve Labours of Heracles Zeus We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover. General information Title of the work Hercules: The Complete Myths of a Legendary Hero Country of the First Edition United States of America Country/countries of popularity United States Original Language English First Edition Date 1997 Georges Moroz, Hercules: The Complete Myths of a Legendary First Edition Details Hero. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Books for Young Readers, 1997, 132 pp. ISBN 0440227321 Genre Myths, Novels Target Audience Young adults Author of the Entry Ayelet Peer, Bar Ilan University, [email protected] Lisa Maurice, Bar Ilan University, [email protected] Peer-reviewer of the Entry Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, [email protected] 1 This Project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 681202, Our Mythical Childhood... The Reception of Classical Antiquity in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to Regional and Global Challenges, ERC Consolidator Grant (2016–2021), led by Prof. -

Megarian Myths: Extrapolating the Narrative Traditions of Megara

Chapter 3 KEVIN SOLEZ – MacEwan University, Edmonton, Alberta [email protected] Megarian Myths: Extrapolating the Narrative Traditions of Megara Studying the local in the framework of localism is to study the parameters that constrain the lives and thoughts of people who conceive of themselves as belonging to a particular place. I am inspired by Conceptual Metaphor Theory,1 where the physical structures of the brain that encode sensory-motor experience are recruited by the brain for cognition about all abstract things.2 The local experience of individuals in their landscape and culture, much of this dependent on their home territory and mobility, is the source domain for their thinking about everything else, including places and people that are not present, and not part of their locale. The local referents and their dynamics - sensory-motor experience in the first place, but also geography, rituals, stories, institutions, ancestries, cuisine, economic activities, etc. – structure the thinking of those embedded in the locale and constitute an individual’s template of cognition. 1 The importance of the local and local experience in Conceptual Metaphor Theory can be seen in the work of Z. Kövecses, e.g. “In many cases the ‘same’ bodily phenomenon may be interpreted differently in different cultures and that activities of the body (and the body itself) are often ‘construed’ differentially in terms of local cultural knowledge.[…] And yet, it seems to me reasonable to suggest that the kinds of bodily experience that form the basis of many conceptual metaphors […] can and do exist independently of any cultural interpretation (be it either conscious or unconscious).