Cuaderno De Documentacion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Deal – the Coordinators

Green Deal – The Coordinators David Sassoli S&D ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first European Parliament and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be 1 February 2020 – H1 2024 the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle President of the European Commission Head of Cabinet Secretary General Chairs and Vice-Chairs Political Group Coordinators EPP S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe ENVI Renew Committee on Europe Dan-Ştefan Motreanu César Luena Peter Liese Jytte Guteland Nils Torvalds Silvia Sardone Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator the Environment, Public Health Greens/EFA GUE/NGL Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Food Safety Pacal Canfin Chair Bas Eickhout Anja Hazekamp Bas Eickhout Alexandr Vondra Silvia Modig Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator S&D S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe EPP ITRE Patrizia Toia Lina Gálvez Muñoz Christian Ehler Dan Nica Martina Dlabajová Paolo Borchia Committee on Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Industry, Research Renew ECR Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Energy Cristian Bușoi Europe Chair Morten Petersen Zdzisław Krasnodębski Ville Niinistö Zdzisław Krasnodębski Marisa Matias Vice-Chair Vice-Chair -

Plusinside Senti18 Cmufilmfest15

Pittsburgh Opera stages one of the great war horses 12 PLUSINSIDE SENTI 18 CMU FILM FEST 15 ‘BLOODLINE’ 23 WE-2 +=??B/<C(@ +,B?*(2.)??) & THURSDAY, MARCH 19, 2015 & WWW.POST-GAZETTE.COM Weekend Editor: Scott Mervis How to get listed in the Weekend Guide: Information should be sent to us two weeks prior to publication. [email protected] Send a press release, letter or flier that includes the type of event, date, address, time and phone num- Associate Editor: Karen Carlin ber of venue to: Weekend Guide, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 34 Blvd. of the Allies, Pittsburgh 15222. Or fax THE HOT LIST [email protected] to: 412-263-1313. Sorry, we can’t take listings by phone. Email: [email protected] If you cannot send your event two weeks before publication or have late material to submit, you can post Cover design by Dan Marsula your information directly to the Post-Gazette website at http://events.post-gazette.com. » 10 Music » 14 On the Stage » 15 On Film » 18 On the Table » 23 On the Tube Jeff Mattson of Dark Star City Theatre presents the Review of “Master Review of Senti; Munch Rob Owen reviews the new Orchestra gets on board for comedy “Oblivion” by Carly Builder,”opening CMU’s film goes to Circolo. Netflix drama “Bloodline.” the annual D-Jam show. Mensch. festival; festival schedule. ALL WEEKEND SUNDAY Baroque Coffee House Big Trace Johann Sebastian Bach used to spend his Friday evenings Trace Adkins, who has done many a gig opening for Toby at Zimmermann’s Coffee House in Leipzig, Germany, where he Keith, headlines the Palace Theatre in Greensburg Sunday. -

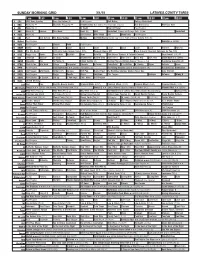

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Sunday Morning Grid 3/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding College Basketball 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Snowboarding U.S. Grand Prix: Slopestyle. (Taped) Red Bull Series PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: Folds of Honor QuikTrip 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Swimfan › (2002) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR T’ai Chi, Health JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Deepak Chopra MD Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs New. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Uncle Buck ›› (1989) 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(Weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule June(weekly) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24 400 400 Hitler's Last Year、 Family Guns、 Family Guns、 WW2 Hell Under the Sea、 Underworld, Inc. Nazi Attack On America、 Nazi World War Weird Apocalypse World War I、 Apocalypse: The Second World My Fighting Season One Strange Rock Long Road Home America's Great War 1917-1918 War 430 430 500 500 Time Scanners、Return From The Dead、Into The Crystal Cave、Viking Apocalypse、 Borneo's Secret Kingdom Chain of Command Hitler's Jurassic Monsters、Secrets of Christ's Tomb: Explorer Special、Invaders、 →Wild Namibia →I Wouldn't Go In There Mystery of The Disappearing Skyjacker、Paranatural II、Secret History of UFO's、Roswell UFO Secrets、Invasion Earth →Wild Botswana: Lion Brotherhood 530 530 600 information 600 630 Brain Games 4、Is It Real?、Mad Scientists 630 700 700 Return of The Lion、Game Of Lions、Caught in the Act V、 Planet Carnivore、Blood Rivals: Lion vs. Buffalo、Brutal Killers、 Dr. K's Exotic Animal ER Cat Wars: Lion vs. Cheetah、Lion vs. Giraffe、Superpride、Blood Rivals: Hippo V. Lion、 Supercar Megabuild2 Car S.O.S.Ⅱ Season 3 Attack of The Big Cats、Big Cat Games、The Jungle King Compilation →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic →CAR S.O.S.Ⅳ Test broadcasting Program(22nd) 730 730 800 800 Two Tales of China、 CAR S.O.S.Ⅲ Big, Bigger, Biggest 2、Nazi World War Weird、Das Reich - Hitler's Death Squad、Chasing UFOs China From Above、 Megafactories →Shido Nakamura's unexpected trip by Golf GTI Dynamic Maritime China 830 830 900 information 900 930 930 Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey、Moon Landings Declassified、Roswell UFO Secrets、 Survive the Wild Wicked Tuna 7 Genius(18h ~11:00) 1000 1000 1030 information 1030 Pope vs. -

Netanyahu Formally Denies Charges in Court

WWW.JPOST.COM THE Volume LXXXIX, Number 26922 JERUSALEFOUNDED IN 1932 M POSTNIS 13.00 (EILAT NIS 11.00) TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 27 SHVAT, 5781 Eye in the sky A joint goal Feminist religious art IAI unveils aerial Amos Yadlin on the need to When God, Jesus surveillance system 6 work with Biden to stop Iran and Allah were women Page 6 Page 9 Page 16 How did we miss Netanyahu formally denies charges in court Judges hint witnesses to be called only after election • PM leaves hearing early the exit • By YONAH JEREMY BOB two to three weeks to review these documents before wit- Prime Minister Benjamin nesses are called, that would ramp? Netanyahu’s defense team easily move the first witness fought with the prosecution beyond March 23. ANALYSIS on Monday at the Jerusalem Judge Rivkah Friedman Feld- • By YONAH JEREMY BOB District Court over calling man echoed the prosecution’s witnesses in his public cor- arguments that the defense A lifetime ago when living ruption trial before the March had between one to two years in northern New Jersey, I 23 election. to prepare for witnesses. But often drove further north for It seemed that the judges ultimately the judges did not work. were leaning toward calling seem anxious to call the first Sometimes the correct exit the first witness in late March witness before March 23. was small and easy to miss. or early April, which they A parallel fight between the But there were around five would present as a compro- sides was the prosecution’s or so exits I could use to avoid mise between the sides. -

Uef-Spinelli Group

UEF-SPINELLI GROUP MANIFESTO 9 MAY 2021 At watershed moments in history, communities need to adapt their institutions to avoid sliding into irreversible decline, thus equipping themselves to govern new circumstances. After the end of the Cold War the European Union, with the creation of the monetary Union, took a first crucial step towards adapting its institutions; but it was unable to agree on a true fiscal and social policy for the Euro. Later, the Lisbon Treaty strengthened the legislative role of the European Parliament, but again failed to create a strong economic and political union in order to complete the Euro. Resulting from that, the EU was not equipped to react effectively to the first major challenges and crises of the XXI century: the financial crash of 2008, the migration flows of 2015- 2016, the rise of national populism, and the 2016 Brexit referendum. This failure also resulted in a strengthening of the role of national governments — as shown, for example, by the current excessive concentration of power within the European Council, whose actions are blocked by opposing national vetoes —, and in the EU’s chronic inability to develop a common foreign policy capable of promoting Europe’s common strategic interests. Now, however, the tune has changed. In the face of an unprecedented public health crisis and the corresponding collapse of its economies, Europe has reacted with unity and resolve, indicating the way forward for the future of European integration: it laid the foundations by starting with an unprecedented common vaccination strategy, for a “Europe of Health”, and unveiled a recovery plan which will be financed by shared borrowing and repaid by revenue from new EU taxes levied on the digital and financial giants and on polluting industries. -

Port Back on Comp Plan

Fifteen and done: Giants devastate Packers in Green Bay /B1 MONDAY CITRUS COUNTY TODAY & Tuesday morning HIGH Partly cloudy, winds 5 to 73 10 mph. Slight chance LOW of rain Tuesday. 47 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JANUARY 16, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 162 NEWS BRIEFS Port back on comp plan Government center to open CHRIS VAN ORMER As part of the groundwork Commissioners (BOCC) portation planner, ex- “One of the recommenda- Tuesday Staff Writer to conduct a feasibility conducted a transmittal plained the background for tions of the 1996 evaluation study for the proposed Port public hearing on the port the need to put back the appraisal report was to re- The new West Citrus Keeping the port project Citrus project, county staff element and voted unani- port element. Jones said the move the port element from Government Center in on course, commissioners on had to put the port element mously to authorize trans- original comprehensive the comprehensive plan,” Meadowcrest opens for Tuesday agreed to add an- back into the comprehen- mittal of the element to plan adopted in 1989 in- Jones said. “The board in business Tuesday other chapter to the county’s sive plan. The Citrus state agencies for review. cluded a ports and aviation morning. comprehensive plan. County Board of County Cynthia Jones, trans- element. See PORT/Page A4 The satellite offices for clerk of court, tax collec- tor, property appraiser and supervisor of elec- tions relocated from their old offices in a Crystal River shopping center on U.S. -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press Galleries

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Media Coordinators: Elizabeth Crowley Wendy A. Oscarson-Kirchner Amy H. Gross James D. Saris HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Molly Cain Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Maureen Groppe, Gannett Washington Bureau, Chair Laura Litvan, Bloomberg News, Secretary Alan K. Ota, Congressional Quarterly Richard Cowan, New York Times Andrew Taylor, Reuters Lisa Mascaro, Las Vegas Sun RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration.