Case 2:04-Cv-00671-TS Document 132 Filed 08/02/05 Page 1 of 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasies and Complexes in the Rorschach Test

Send Orders of Reprints at [email protected] The Open Psychology Journal, 2013, 6, 1-5 1 Open Access Trauma and the Father Image: Fantasies and Complexes in the Rorschach Test Settineri Salvatore1, Lo Presti Eleonora2, Liotta Marco3 and Mento Carmela*,4 1Clinical Psychology, Department of Human and Social Science, University of Messina, Italy 2University of Messina, Italy 3Psychological Sciences, University of Messina, Italy 4Clinical Psychology, Department of Neurosciences, University of Messina, Italy Abstract: In the interpretation of the Rorschach test, the features of the table IV inkblot evoke a dimension of authority, morals and related emotions. Interestingly, the father figure is related to ego development and also guides towards matur- ity via more evolved emotions such as feelings of shame and guilt. In some cases these feelings are found to be lacking in adults experiencing depression. The aim of this work is to analyze the relationship between the representational world in relation to the father figure and depressive mood disorders. The group of subjects is composed of 25 patients who had a psychiatric diagnosis of "Depressive episode". The presence of specific phenomena brings out the complexes, the uneasy and conflictual relationship with the father figure submerged in the unconscious thus emerges. Shock is thereby mani- fested in relation to the black in which the large, dark, and blurred stimulus is perceived as sinister, threatening and dan- gerous. The trauma emerges in the result of a relationship with a father who has not allowed the child to manage similari- ties and differences. From the nature of the answers of the Rorschach protocols, it emerges that the symbolic abilities of subjects are not fully developed or have been attacked by an early trauma. -

Adaptation of Psychological Assessment Tools for Administration by Blind and Visually Impaired Psychologists and Trainees

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 428 487 EC 307 090 AUTHOR Keller, Richard M. TITLE Adaptation of Psychological Assessment Tools for Administration by Blind and Visually Impaired Psychologists and Trainees. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 14p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Graduate Students; Higher Education; Intelligence Tests; *Psychological Testing; *Psychologists; *Test Interpretation; Testing; *Testing Problems; *Visual Impairments IDENTIFIERS Bender Visual Motor Gestalt Test; Rorschach Test; Thematic Apperception Test; *Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Revised) ABSTRACT This paper focuses on challenges to psychologists and psychology graduate students who are blind or visually impaired in the administration and scoring of various psychological tests. Organized by specific tests, the paper highlights those aspects of testing which pose particular difficulty to testers with visual impairments and also describes methods by which some tests can be adapted to mediate these challenges. Specific tests include:(1) the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised verbal subtests and performance subtests;(2) the Visual Motor Gestalt Test; (3) the Rorschach Test;(4) the Thematic Apperception Test; and (5) projective drawing tests. (CR) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ******************************************************************************** ADAPTATION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT TOOLS FOR ADMINISTRATION BY BLIND AND VISUALLY IMPAIRED PSYCHOLOGISTS AND TRAINEES Richard M. Keller BEST COPY AMLABLE Teachers College, Columbia University ;(3 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND EDJéCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS 0 CENTER (ERIC) BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. -

The Swami and the Rorschach: Spiritual Practice, Religious

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Religious Studies College of Arts & Sciences 1998 The wS ami and the Rorschach: Spiritual Practice, Religious Experience, and Perception Diane Jonte-Pace Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/rel_stud Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jonte-Pace, Diane. "The wS ami and the Rorschach: Spiritual Practice, Religious Experience, and Perception." The nnI ate Capacity: Mysticism, Psychology, and Philosophy. Ed. Robert K. C. Forman. New York: Oxford UP, 1998. 137-60. The wS ami and the Rorschach by Diane Jonte-Paace, 1998, reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/ product/the-innate-capacity-9780195116977?q=Innate%20Capacity&lang=en&cc=us# This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEVEN The Swami and the Rorschach Spiritual Practice, Religious Experience, and Perception DIANE JONTE-PACE NEARLY A CENTURY after William James initiated the psychological study of mysti cism with the publication of The Varieties of Religious Experience, 1 Robert Forman has returned to James's project by issuing a call for a psychologia perennis.2 This "perennial psychology" would investigate mystical or nonordinary states of con sciousness and the transformative processes that produce them. Whereas James of fered a typology of mystical experience structured around the mysticism of the "healthy minded" and the mysticism of the "sick soul," Forman proposes an inquiry that goes well beyond the work of his predecessor. -

The Projective Technique of Personality Study As Illustrated by the Rorschach Test, Its History, Its Method, and Its Status

The Projective Technique of Personality Study as Illustrated by the Rorschach Test, its History, its Method, and its Status Item Type Thesis Authors Krug, John E. Download date 04/10/2021 10:28:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/4761 THE PROJECTIVE TECHNIQUE OF PERSONALITY STUDY AS ILLUSTRATED BY THE RORSCHACH TEST, ITS HISTORY, ITS METHOD, ill~D ITS STATUS A Thesis Presented to the raculty of the Department of Education Indiana State Teachers College ,) ,._, , ., J, \,, .", " ) "...:-._._._---~ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Education Number 609 by John Eo Kr.ug August 1949 The thesis of --=J:...:::o~hn:=.::.._=E::.:o~K::.:r:...u=:;g~ , Contribution of the Graduate School, Indiana State Teachers College, Number 602, under the title The Projective Technique of Personality Study As Illus trated By The Rorschach TeBt, Its History, Its Method, And Its Status is hereby approved as counting toward the completion of the Master's degree in the amount of __S__ hours' credito Committee on thesis: Chairman Representative of English Department: ~V?CL~/~~I Date of Acceptance .•·r;u¥#K TABLE OF OONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 10 THE PROBLEM AND OBJECTIVES OF THIS THESIS " o .. .. 1 The problem and the procedure .. •• 1 Statement of the problem •• • .••.• 1 Order of procedure ••. •...• .. 1 Introduction and statement of objectives ... 0 2 Organization of this paper .•.•..• .. •• 5 II. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF INK BLOT TESTING • .. •• 7 Introduction .. .. •. .. 7 Development ... .•• 8 Conclusion ••. .••... .. 20 III" ,THE METHOD AND PROCEDURE OF' THE RORE:CHACH TEST' .. 21 Introduction .. ..... 21 Background of the examiner . -

A Study of the Efficacy of the Group Rorschach Test in Predicting Scholastic Achievement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1947 A study of the efficacy of the group Rorschach test in predicting scholastic achievement. Marjorie H. Brownell University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Brownell, Marjorie H., "A study of the efficacy of the group Rorschach test in predicting scholastic achievement." (1947). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1359. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1359 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDY of the EFFICACY of the GROUP RORSCHACH EST IN PREDICTING SCHOLASTIC ACHIEVEMENT BROWNELL-1947 m A STUDY OF THE EFFICACY OF THE GROUP KOKSCilACH 3HGW IN PREDICTING SCHOLASTIC ACHIEVEMENT by MARJORIE BROWNELL THESIS "SUBMITTED FOR TEE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS MY 1947 TABLE OP CONTENTS fag© Introduction - - - - - . 1 Survey of Literature I. Historical - . — — — — 3 II. Group Rorschach m 5 III, Reliability and Validity 6 IV, Present Status of the Rorschach - - g V. Applications lQ VI. Achievement Studies Problem - - im ----- id, ft Subjects and Apparatus and l&terials I, Subjects ----------««...,. 2.9 II. Apparatus and Materials X9 Procedure I. Method of Administration 21 II. Testing Sessions ^2 III. Scoring Technique ------ _ 23 Results and Discussion I. Results - 37 II. Discussion 53 Summary and Conclusions - -- -- - „ 41 Appendix 43 I CM a. US GO INTRODUCTION Personality rnay be measured either by pencil-and-paper tests in which the subject merely answers a number of printed questions concerning his likes and dislikes, feelings and attitudes, or by the projective type of test. -

Children's Creativity and Personal Adaptation Resources

behavioral sciences Article Children’s Creativity and Personal Adaptation Resources Vera G. Gryazeva-Dobshinskaya, Yulia A. Dmitrieva *, Svetlana Yu. Korobova and Vera A. Glukhova Laboratory of Psychology and Psychophysiology of Stress-Resistance and Creativity, Scientific and Educational Center “Biomedical Technologies”, Higher Medical and Biological School, South Ural State University, 454080 Chelyabinsk, Russia; [email protected] (V.G.G.-D.); [email protected] (S.Y.K.); [email protected] (V.A.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-961-785-2908 Received: 28 November 2019; Accepted: 30 January 2020; Published: 3 February 2020 Abstract: The study provides insights into the aspects of creativity, the structure of psychometric intelligence, and personal adaptation resources of senior preschool children. Creativity and intelligence are presented as general adaptation resources. Existing studies of creative ability and creativity as integral individual characteristics in the context of adaptation are analyzed. The aim is to identify varied sets of creativity and personal adaptation resource markers that differentiate groups of children in order to determine possible strategies for adaptation, preservation, and development of their creative abilities at the beginning of lyceum schooling. It embraces the use of the E. Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) (figural version), the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC), and the G. Rorschach Test. A sample of the study consisted of 122 children, aged 6–7 and enrolled in a school. The average IQ score among the children was above 115 (M = 133.7, σ = 9.9). The entire sample was divided into four groups by the originality-elaboration ratio according to the TTCT. -

Rorschach Inkblot Test: an Overview on Current Status

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (Online) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (Print) Volume 8, Issue 4, Oct- Dec, 2020 DIP: 18.01.075/20200804, DOI: 10.25215/0804.075 http://www.ijip.in Research Paper Rorschach Inkblot Test: an overview on current status Anwesha Mondal1*, Manish Kumar2 ABSTRACT The Rorschach Inkblot Test has the dubious distinction of being simultaneously the most cherished and the most criticized of all psychological assessment tools. Till date on one hand it is held in great esteem by many for its ability to access intrapsychic material, whereas others consider it to be a prime example of unscientific psychological assessment. However, the Rorschach Inkblot Test is extensively used since it is found to be a tool to unearth the deep-rooted emotional conflicts. Despite limitations and various drawbacks Rorschach Inkblot Test is widely and rigorously used in different clinical settings and has considerable potential to contribute in the field of psychology in the future years. Hence, an attempt has been made to understand the current status of Rorschach Inkblot Test. Keywords: Rorschach, current, status ersonality refers to the patterns of thoughts, feelings, social adjustments and behaviours consistently exhibited by an individual over time that strongly influence an individual’s P expectations, self-perceptions, values, attitudes, and predicts reactions to people, problems and stress. Personality is referred to as the complexity of psychological systems that contribute to unity and continuity in the individual’s conduct and experience, both as it is expressed and as it is perceived by that individual and others. In the 1930s personality psychology emerged as a discrete field of study where personality assessment received its important impetus. -

Infleunce of Induced Mood on the Rorschach Performance

A Dissertation entitled The Impact of Induced Mood on Visual Information Processing by Nicolae Dumitrascu Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Clinical Psychology Joni L. Mihura, Ph.D., Committee Chair Gregory J. Meyer, Ph.D., Committee Member John D. Jasper, Ph.D., Committee Member Mary E. Haines, Ph.D., Committee Member Jeanne Brockmyer, Ph.D., Committee Member Patricia Komuniecki, Ph.D., Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2011 ii An Abstract of The Impact of Induced Mood on Visual Information Processing by Nicolae Dumitrascu Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Clinical Psychology The University of Toledo December 2011 Previous research in the areas of social psychology, perception, memory, thinking, and creativity suggests that a happy mood promotes global, flexible, top-down processing, whereas a sad mood leads to a more analytic, less flexible, bottom-up processing. The main goal of this study was to determine if selected variables of the Rorschach Inkblot Test can capture the mood effects associated with a happy and a sad mood, respectively. A linear increase was predicted in Global Focus-W, Global Focus Synthesis-WSy, Synthesis-Sy, Perceptual Originality-Xu%, and Ideational Flexibility- Content Range and a linear decrease was predicted in Local Focus-Dd across the three mood conditions (sad/neutral/happy). Also, an increase was predicted in Perceptual Inaccuracy-X-% in both happy and sad mood conditions as compared to neutral. A secondary goal of this study was to replicate the findings showing a global/local bias as a function of mood state on two perceptual tasks requiring hierarchical processing. -

Perception and Language: Using the Rorschach with People with Aphasia V

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 1-1-2016 Perception and Language: Using the Rorschach with People with Aphasia V. Terri Collin Dilmore Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Collin Dilmore, V. (2016). Perception and Language: Using the Rorschach with People with Aphasia (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/93 This Worldwide Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERCEPTION AND LANGUAGE: USING THE RORSCHACH WITH PEOPLE WITH APHASIA A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By V. Terri Collin Dilmore, M.A. August 2016 Copyright V. Terri Collin Dilmore 2016 PERCEPTION AND LANGUAGE: USING THE RORSCHACH WITH PEOPLE WITH APHASIA By V. Terri Collin Dilmore Approved July 27, 2016 ________________________________ ________________________________ Alexander Kranjec, Ph.D. Sarah Wallace, Ph.D., CCC-SLP Assistant Professor of Psychology Associate Professor of Speech-Language Pathology (Committee Director) (Committee Co-Director) ________________________________ ________________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Lori Koelsch, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty Graduate School of Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology Liberal Arts Director of Undergraduate Psychology Professor of Philosophy (Committee Reader) ________________________________ Leswin Laubscher, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Psychology Associate Professor of Psychology iii ABSTRACT PERCEPTION AND LANGUAGE: USING THE RORSCHACH WITH PEOPLE WITH APHASIA By V. -

Critique of Projective Tests

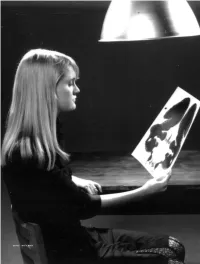

WARHOL CREDIT HERE by Scott O. Lilienfeld, James M. Wood and Howard N. Garb What’s Wrong with This PICTURE PICTURE? PHOTOGRAPHS BY JELLE WAGAANER PSYCHOLOGISTS OFTEN USE THE FAMOUS RORSCHACH INKBLOT TEST AND RELATED TOOLS TO ASSESS PERSONALITY AND MENTAL ILLNESS. BUT RESEARCH SHOWS THAT INSTRUMENTS ARE FREQUENTLY INEFFECTIVE FOR THOSE PURPOSES www.sciam.com SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN 41 What if you were asked to describe images you saw in an inkblot or to invent a story for an ambiguous illustration— say, of a middle-aged man looking away from a woman who was grabbing his arm? To comply, you would draw on your own emotions, experiences, memories and imagination. You would, in short, project yourself into the images. Once you did that, many practicing psychologists would assert, trained evaluators could mine your musings to reach conclusions about your personality traits, unconscious needs and overall mental health. But how correct would they be? The answer is important Standardization is needed because seemingly trivial differences because psychologists frequently apply such “projective” in- in the way an instrument is administered can affect a person’s struments (presenting people with ambiguous images, words responses. Norms provide a reference point for determining or objects) as components of mental assessments, and because when someone’s responses fall outside an acceptable range. the outcomes can profoundly affect the lives of the respondents. In the 1970s John E. Exner, Jr., then at Long Island Uni- The tools often serve, for instance, as aids in diagnosing men- versity, ostensibly corrected those problems in the early tal illness, in predicting whether convicts are likely to become Rorschach test by introducing what he called the Comprehen- violent after being paroled, in assessing the mental stability of sive System. -

Indicators of Empathy in the Rorschach Inkblot Test

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1989 Indicators of Empathy in the Rorschach Inkblot Test Elaine D. Rado Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Rado, Elaine D., "Indicators of Empathy in the Rorschach Inkblot Test" (1989). Master's Theses. 3594. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3594 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Elaine D. Rado INDICATORS OF EMPATHY IN THE RORSCHACH INK BLOT TEST by Elaine D. Rado A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts April 1989 (c) 1989, Elaine D. Rado ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would primarily like to thank my thesis committee, director, Dr. James Johnson, and reader, Dr. Al DeWolfe, for their willingness to take on this project with me, as well as for their support, encouragement, understanding and wisdom. I would also like to acknowledge the role of Dr. Marvin Acklin in organizing the archive used in this study, and thank Gene Alexander and Rachel Albrecht for their preliminary work with that data. ii VITA The author, Elaine Dorothy Rado, is the daughter of Jane Port Rado and Ernest David Rado. -

The Rorschach As a Diagnostic Aid in Differentiating the Bipolar Affective Disorder from the Schizophrenic Disorder

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-1985 The Rorschach as a Diagnostic Aid in Differentiating the Bipolar Affective Disorder from the Schizophrenic Disorder Stephen James Newman Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Psychiatric and Mental Health Commons, and the Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Stephen James, "The Rorschach as a Diagnostic Aid in Differentiating the Bipolar Affective Disorder from the Schizophrenic Disorder" (1985). Dissertations. 2346. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/2346 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RORSCHACH AS A DIAGNOSTIC AID IN DIFFERENTIATING THE BIPOLAR AFFECTIVE DISORDER FROM THE SCHIZOPHRENIC DISORDER by Stephen James Newman A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Department of Counseling and Personnel Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1985 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE RORSCHACH AS A DIAGNOSTIC AID IN DIFFERENTIATING THE BIPOLAR AFFECTIVE DISORDER FROM THE SCHIZOPHRENIC