John Paul II As Philosopher Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family JPI 510/729 Theological Anthropology McCarthy • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Burns, J., Ed. Theological Anthropology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981. • Balthasar, Hans Urs. The Christian State of Life. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983. • ______. Theo-Drama II, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990. ISBN 0898702879 • ______. Theo-Drama III. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 11992. ISBN 089870295X. • De Lubac, H. The Drama of Atheist Humanism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995. ISBN: 089870443X • De Lubac, H. A Brief Catechesis on Nature and Grace. Ignatius Press, 1984. ISBN: 0898700353 • John Paul II. Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body. Pauline, 1997. • Schmitz, K. The Gift: Creation. Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, 1982. • Scola. The Nuptial Mystery. Trans. M. Borras. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2005. • Spaemann, R. Essays in Anthropology – Variations on a Theme. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2010. JPI 532/707 Biblical Theology of Marriage and Family (OT) Atkinson • Holy Scriptures [The most recent edition of Ignatius Press’ RSV is particularly good.] • Biblical and Theological Foundation of the Family, Joseph Atkinson (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2014). • Jean-Baptiste Edart (with Himbaza and Schenker). The Bible on the Question of Homosexuality. (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2012). JPI 550/850 Gender and the Sexual Difference D.L. Schindler • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Simon Baron-Cohen, The Essential Difference. (New York: Basic Books, 2003). • John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: Theology of the Body. • Eve Tushnet, Gay and Catholic (Ave Maria Press, 2014). -

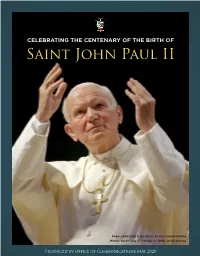

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

Download Download

Implementing the Principles of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church in Catholic Higher Education1 His Eminence Renato Raffaele Cardinal Martino The purpose of this discussion is to share a refl ection on the imple- mentation of Catholic Social Teaching (CST) in the ministry of Catholic higher education. In particular, I wish to highlight the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church2 that was completed by the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace at the request of the Servant of God, Pope John Paul II. Designed to be a user-friendly synthesis of the principles of CST, the Compendium has proven to be an extremely practical and substantial resource. It has now been translated into 40 different lan- guages and is widely available throughout the world. In a certain sense, the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church has been called “the Church’s best kept secret.” Why is this the case? Before the publication of the Compendium, perhaps because the social teach- ings of the popes were responding to specifi c situations (such as the cir- cumstances of the workers at the end of nineteenth century examined by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Rerum novarum3), a well-structured exposition of the social doctrine of the Church did not exist. It was not until 1999 that Pope John Paul II, in his exhortation Ecclesia in America4, promised a document that would synthesize the social doc- trine of the Church. He then asked the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace to prepare such a document—the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church—which was fi rst released on October 25, 2004. -

Thomas Aquinas' Metaphysics of Creatio Ex Nihilo

Studia Gilsoniana 5:1 (January–March 2016): 217–268 | ISSN 2300–0066 Andrzej Maryniarczyk, S.D.B. John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin Poland PHILOSOPHICAL CREATIONISM: THOMAS AQUINAS’ METAPHYSICS OF CREATIO EX NIHILO In keeping with the prevalent philosophical tradition, all philoso- phers, beginning with the pre-Socratics, through Plato and Aristotle, and up to Thomas Aquinas, accepted as a certain that the world as a whole existed eternally. They supposed that only the shapes of particu- lar things underwent transformation. The foundation for the eternity of the world was the indestructible and eternal primal building material of the world, a material that existed in the form of primordial material elements (the Ionians), in the form of ideas (Plato), or in the form of matter, eternal motion, and the first heavens (Aristotle). It is not strange then that calling this view into question by Tho- mas Aquinas was a revolutionary move which became a turning point in the interpretation of reality as a whole. The revolutionary character of Thomas’ approach was expressed in his perception of the fact that the world was contingent. The truth that the world as a whole and eve- rything that exists in the world does not possess in itself the reason for its existence slowly began to sink into the consciousness of philoso- phers. Everything that is exists, as it were, on credit. Hence the world and particular things require for the explanation of their reason for be- ing the discovery of a more universal cause than is the cause of motion. This article is a revised and improved version of its first edition: Andrzej Maryniarczyk SDB, The Realistic Interpretation of Reality. -

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner Proceedings from the First Conference of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas held in the United States of America Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by John P. Hittinger, Daniel C. Wagner and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7554-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7554-7 DEDICATION TO THE MEMORY OF REV. VICTOR BREZIK, C.S.B. 1913-2009 TEXAN—BASILIAN—THOMIST Father Victor Brezik, who joined the University of St. Thomas faculty in 1954, adopted as his personal motto, “Dare to do whatever you can,” from his favorite philosopher, St. Thomas Aquinas. Fr. Brezik’s philosophical attitude and vision inspired generations of students and colleagues. In addition to his many contributions to the University, Fr. Brezik co-founded with Hugh Roy Marshall the University of St. Thomas’ Center for Thomistic Studies in 1975. The Center for Thomistic Studies, where the wisdom of Thomas Aquinas could be brought to bear on the problems of the contemporary world, was Fr. -

The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: the Case of Gaudium Et Spes

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 45 Number 2 Volume 45, 2006, Number 2 Article 6 The Use of Philosophical Principles in Catholic Social Thought: The Case of Gaudium et Spes Rev. Joseph W. Koterski, S.J. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE USE OF PHILOSOPHICAL PRINCIPLES IN CATHOLIC SOCIAL THOUGHT: THE CASE OF GAUDIUM ET SPES REVEREND JOSEPH W. KOTERSKI, S.J.t It is common to find individuals who are very attracted to questions of social justice and others quite uninterested, or even suspicious.1 At both extremes there are dangers to avoid. On the one hand, Catholicism may never be reduced to the concerns of "the social gospel" apart from the rest of the faith.2 On the other hand, the Church's social teachings, especially in the clear articulation given by recent popes and the Second Vatican Council, are not peripheral to the faith, not something purely optional, as if the essence of Catholicism were a matter of spirituality to the exclusion of morality.3 Like the rest of Catholic moral theology, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) has roots both in revelation and reason,4 and anyone interested in t Rev. Joseph W. -

Mulieris Dignitatem Twenty Years Later: an Overview of the Document and Challenges

MULIERIS DIGNITATEM TWENTY YEARS LATER: AN OVERVIEW OF THE DOCUMENT AND CHALLENGES Sr. Prudence Allen, R.S.M.g INTRODUCTION August 15, 2008, marked the twentieth anniversary of the promulgation of the apostolic letter Mulieris Dignitatem.1 This Article provides an overview of Mulieris Dignitatem, looking at some of the key principles Pope John Paul II articulates. This Article describes how the principles were innovative with respect to previous teaching about women, evaluates the principles in light of present developments in our American culture, and suggests some possible ways we might consider acting on these principles for a new evangelization. Reflections proceed chronologically and thematically through Mulieris Dignitatem. This Article discusses the following themes: Part I, the truth about the human being; Part II, Mary, the Mother of God, as our pilgrim guide; Part III, communio in the Holy Trinity as analogous for communio of women and men; Part IV, the rupture within a person and among persons through sin; Part V, encountering Jesus Christ as enabling this rupture to be overcome; Part VI, the mandate to release each woman’s genius in the face of evil for the good of all; Part VII, paradigm dimensions of women’s vocations in the Church; Part VIII, complementarity through spousal bonds; and Part IX, plans of action through educating on the nature and dignity of women and through ransoming language. g Sr. Prudence Allen, R.S.M., Ph.D., is a Professor, Department of Philosophy, at the St. John Vianney Theological Seminary in Denver, Colorado. 1. Pope John Paul II, Mulieris Dignitatem [Apostolic Letter on the Dignity and Vocation of Women] (1988) [hereinafter Mulieris Dignitatem]. -

John Paul II and the Law

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 21 Article 7 Issue 1 Symposium on Pope John Paul II and the Law 1-1-2012 John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration Nicholas DiMarzio Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Nicholas DiMarzio, John Paul II: Migrant Pope Teaches on Unwritten Laws of Migration, 21 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 191 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol21/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PAUL II: MIGRANT POPE TEACHES ON UNWRITTEN LAWS OF MIGRATION MOST REVEREND NICHOLAS DiMARzio, PH.D., D.D.* INTRODUCTION His Holiness, John Paul II, of happy memory, was one of the greatest teaching popes in the Church's history. He has given the Church a body of teaching that will take generations to fathom. This issue of the Notre DameJournal of Law, Ethics & Pub- lic Policy is an attempt to collate his teaching regarding law and public policy. This article will attempt to bring together John Paul II's thought and teaching on migration, which is implicit in many of his teachings, and also explicit in many of his discourses. Underlying his teaching is an understanding of human dignity which became the departure point forJohn Paul II's understand- ing of natural law. -

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005)

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005) His Holiness John Paul II (16 Oct. 1978-2 April 2005) was the first Slav and the first non-Italian Pope since Hadrian VI. Karol Wojtyla was born on 18 May 1920 at Wadowice, an industrial town south-west of Krakow, Poland. His father was a retired army lieutenant, to whom he became especially close since his mother died when he was still a small boy. Joining the local primary school at seven, he went at eleven to the state high school, where he proved both an outstanding pupil and a fine sportsman, keen on football, swimming, and canoeing (he was later to take up skiing); he also loved poetry, and showed a particular flair for acting. In 1938 he moved with his father to Krakow where he entered the Jagiellonian University to study Polish language and literature; as a student he was prominent in amateur dramatics, and was admired for his poems. When the Germans occupied Poland in September 1939, the university was forcibly closed down, although an underground network of studies was maintained (as well as an underground theatrical club which he and a friend organised). Thus he continued to study incognito, and also to write poetry. In winter 1940 he was given a labourer’s job in a limestone quarry at Zakrówek, outside Krakow, and in 1941 was transferred to the water- purification department of the Solway factory in Borek Falecki; these experiences were to inspire some of the more memorable of his later poems. In 1942, after his father’s death and after recovering from two near-fatal accidents, he felt the call to the priesthood, began studying theology clandestinely and after the liberation of Poland by the Russian forces in January 1945 was able to rejoin the Jagiellonian University openly. -

Duns Scotus on Common Natures And

DUNS SCOTUS ON COMMON NATURES AND “CARVING AT THE JOINTS” OF REALITY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Andrew C. Helms ______________________________ Richard Cross, Director Graduate Program in Philosophy Notre Dame, Indiana March 2016 © Copyright 2016 Andrew Chad Helms DUNS SCOTUS ON COMMON NATURES AND “CARVING AT THE JOINTS” OF REALITY Abstract by Andrew Chad Helms Despite the puzzles of interpretation it engenders, John Duns Scotus’s theory of common natures is widely cited as an example of scholastic “realism.” Common natures serve a variety of functions in Scotus’s system, providing the “real unity” which serves as the subject for Aristotelian science. The “proper passions” of substances – characteristics which serve to identify substances by type, but do not formally belong to the essence of a subject – are ontologically dependent on common natures according to kind. And Scotus operates on the assumption that it is the description of created subjects according to their common natures which is the most fundamental description of them. Thus, for Scotus, common natures and their relations determine what we might call the “structure” of reality. But not every “subject of a science” is a common nature. According to Scotus, “being,” the subject of “metaphysics,” does not have the same real unity as the natural groupings under the ten categories of Aristotle. As a consequence of this, the “transcendental passions of being” include predicates which do not possess the “real unity” of a common nature, because they are too abstract or generic to do so. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF JOHN PAUL II ON THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF POPE LEO XIII Venerable Brothers, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen,1. The Pontifical Committee for Historical Sciences has most appropriately wished to commemorate the centenary of the death of Pope Leo XIII, of venerable memory. In fact, my illustrious Predecessor did not limit himself to founding the Cardinals' Commission for the promotion of historical studies, which gave birth to today's Pontifical Committee for Historical Sciences, but he also gave an effective impetus to the historical sciences by opening the Vatican Secret Archives and the Vatican Apostolic Library.I am therefore delighted at this initiative and I am pleased to greet each of you who in these days have come to honour the memory of such an enlightened Pontiff, emphasizing in particular his merits in the field of the historical sciences.2. As is well known, Leo XIII's influence effectively extended to the various contexts of the Church's pastoral action and commitment to culture. I have had various opportunities to reflect on some of these on previous occasions. I am thinking, for example, of Pope Pecci's particular concern for the social problems arising in the second half of the 19th century, which he expressly addressed in the Encyclical Letter Rerum Novarum. I also dedicated an Encyclical, Centesimus Annus, to this theme of the Church's social doctrine, with ample references to that fundamental Document (cf. nn. 4-11).Moreover, I recall the strong encouragement that Leo XIII gave to the renewal of philosophical and theological studies, in particular with the publication of the Encyclical Letter Aeterni Patris, through which he also contributed significantly to the development of Neothomism. -

John Cardinal Newman and Ex Corde Ecclesiae

162 Catholic Education/December 2004 WHAT WOULD NEWMAN DO? JOHN CARDINAL NEWMAN AND EX CORDE ECCLESIAE STEPHEN J. DENIG Niagara University John Paul II’s 1990 apostolic exhortation Ex Corde Ecclesiae and subsequent legislation require those teaching theological disciplines in Catholic univer- sities to have a mandatum. This article explores the thought of John Cardinal Newman with a view to defending a position, consistent with Newman’s thought, relative to the seeking and acceptance of a mandatum. INTRODUCTION In the June 2003 edition of Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice, Heft detailed the work between one Catholic diocese, the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, and one Roman Catholic university, the University of Dayton, as together they sought to implement the Vatican decree, Ex Corde Ecclesiae (ECE; John Paul II, 1990). Of particular con- cern in the Heft essay was the mandatum, a requirement that a Catholic teaching a Catholic theological discipline at a Catholic university have the approval of competent ecclesiastical authority (John Paul II, 1990, para. 4.3). Thus, the mandatum is a statement by an ecclesiastical authority, gen- erally the ordinary of the diocese, that the Catholic theologian is teaching in communion with the Church. As Heft opined in another essay, it is a recognition by the bishop that the theologian is teaching in communion with the Church. There may also be good reason for a particular theologian not to accept a mandatum; nor should anyone conclude that a theologian without it is, by that fact alone, not in full communion with the Church. There is an important dis- tinction between teaching in full communion with the Church and being rec- ognized officially as doing so by the bishop.