Toward Understanding the Jesuit Brother's Vocation, Especially As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

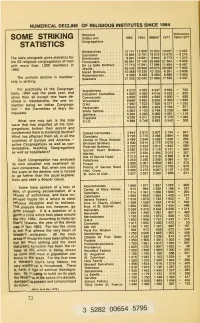

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Glossary, Bibliography, Index of Printed Edition

GLOSSARY Bishop A member of the hierarchy of the Church, given jurisdiction over a diocese; or an archbishop over an archdiocese Bull (From bulla, a seal) A solemn pronouncement by the Pope, such as the 1537 Bull of Pope Paul III, Sublimis Deus,proclaiming the human rights of the Indians (See Ch. 1, n. 16) Chapter An assembly of members, or delegates of a community, province, congregation, or the entire Order of Preachers. A chapter is called for decision-making or election, at intervals determined by the Constitutions. Coadjutor One appointed to assist a bishop in his diocese, with the right to succeed him as its head. Bishop Congregation A title given by the Church to an approved body of religious women or men. Convent The local house of a community of Dominican friars or sisters. Council The central governing unit of a Dominican priory, province, congregation, monastery, laity and the entire Order. Diocese A division of the Church embracing the members entrusted to a bishop; in the case of an archdiocese, an archbishop. Divine Office The Liturgy of the Hours. The official prayer of the Church composed of psalms, hymns and readings from Scripture or related sources. Episcopal Related to a bishop and his jurisdiction in the Church; as in "Episcopal See." Exeat Authorization given to a priest by his bishop to serve in another diocese. Faculties Authorization given a priest by the bishop for priestly ministry in his diocese. Friar A priest or cooperator brother of the Order of Preachers. Lay Brother A term used in the past for "cooperator brother." Lay Dominican A professed member of the Dominican Laity, once called "Third Order." Mandamus The official assignment of a friar or a sister to a Communit and ministry related to the mission of the Order. -

Religious Consecration and the Solemnity of the Vow in Thomas Aquinas’S Works

Mirator 19:1 (2018) 32 Towards a Sacralization of Religious Vows? Religious Consecration and the Solemnity of the Vow in Thomas Aquinas’s Works AGNÈS DESMAZIÈRES homas Aquinas most likely took the Dominican cloth in 1244, in Naples, against the will of This parents who had destined him to the well-established Benedictine convent of the Monte Cassino, where he had been schooled. Kidnapped by his brothers, he spent two years imprisoned in the family castles of Montesangiovanni and Roccasecca, before being released and joining again the Dominicans. The various biographers of Thomas Aquinas granted importance to this episode, relating it with lively and epic details. Marika Räsänen has skillfully demonstrated how the episode of Thomas’s change of clothing was crucial in the construction of the ‘Dominican identity’ in a time when the Order of Preachers was struggling recruiting new candidates.1 Yet, I would highlight in this article a complementary issue: when Thomas Aquinas entered the Dominican Order, the doctrine and rites of incorporation to a religious order were still in a phase of elaboration. Thomas’s doctrine itself evolved significant- ly, moving from a juridical conception of religious vows, characteristic of his early writings, to a sacral one, inspired by a return to patristic and monastic traditions, in his later works. In the first centuries after Christ, the monk accomplished his integration to the monastery through a simple change of clothing, which intervened after a period of probation, lasting from a few days to a full year. At first, the commitment to a monastic rule was only tacit. -

Road to Emmaus Journal

A JOURNAL OF ORTHODOX FAITH AND CULTURE ROAD TO EMMAUS Help support Road to Emmaus Journal. The Road to Emmaus staff hopes that you find our journal inspiring and useful. While we offer our past articles on-line free of charge, we would warmly appreciate your help in covering the costs of producing this non-profit journal, so that we may continue to bring you quality articles on Orthodox Christianity, past and present, around the world. Thank you for your support. Please consider a donation to Road to Emmaus by visiting the Donate page on our website. WHERE THE CROSS DIVIDES THE ROAD: THOUGHTS ON ORTHODOXY AND ISLAM In Part II of a wide-ranging interview, Dr. George Bebawi speaks of his experience of Orthodoxy in England with Russian Orthodox émigrés, clergy, and theologians; his concern about the vul- nerability of Christian youth in the West; and his observations on Judaism and Islam in relation to Orthodoxy. Born in Egypt in 1938, Dr. George graduated from the Coptic Orthodox Theological College in Cairo after a rich spiritual youth spent in the company of contemporary 20th-century Coptic Egyptian desert fathers of Cairo and Scetis. (See Road to Emmaus, Summer, 2009, Issue 38). He went on to attend Cambridge University on scholarship, where he studied Theology, Patristics, and Biblical Criticism, receiving an M.Lit and Ph.D at Cambridge University in 1970. Dr. George taught Theology, Patristics, Church History, and Islamic studies at Orthodox, Catholic and Prot- estant seminaries in Europe, the Middle East, and the United States. His hopes for Christian unity also motivated him to serve on various committees of the World Council of Churches and in the Secretariat for Christian Unity at the Vatican. -

TOWARDS a NEW IDENTITY the Vocation and Mission of Lay Brother in the Order Rome 2002

Order of the Discalced Brothers of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel P. Camilo Maccise TOWARDS A NEW IDENTITY The vocation and mission of Lay Brother in the Order Rome 2002 INTRODUCTION A present day topic 1. For some years now I have wanted to propose to the Order a reflection on the vocation and mission of the brothers in our religious family. Various circumstances obliged me to delay its preparation, especially the expectation for the last seven years of the publication of a document from the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life on the topic, which was requested by the Synod on consecrated life(1). Since my second sexennium as Superior General is coming to a close I decided to turn this desire into reality. In effect, I consider it urgent and topical to offer some considerations on the theme in the light of history, present-day challenges and future prospects for this form of vocation within the Teresian Carmel. Even though it is true we are juridically a clerical Institute(2), at Carmel's beginnings there was no distinction between cleric and lay members. All were simply "Brothers"(3). As late as 1253, the Prior General of the Order was a lay brother. The Order came to know, like other religious families, the phenomenon of clericalization, which became a char- acteristic of religious life in the West. Our senior members know how much the distinction be- tween “Brothers” and "Fathers" had its effect on mentalities, customs and ways of living. 2. -

Book of Common Prayer, Formatted As the Original

The Book of Common Prayer, Formatted as the original This document was created from a text file through a number of interations into InDesign and then to Adobe Acrobat (PDF) format. This document is intended to exactly duplicate the Book of Common Prayer you might find in your parish church; the only major difference is that font sizes and all dimensions have been increased slightly (by about 12%) to adjust for the size difference between the BCP in the pew and a half- sheet of 8-1/2 X 11” paper. You may redistribute this document electronically provided no fee is charged and this header remains part of the document. While every attempt was made to ensure accuracy, certain errors may exist in the text. Please contact us if any errors are found. This document was created as a service to the community by Satucket Software: Web Design & computer consulting for small business, churches, & non-profits Contact: Charles Wohlers P. O. Box 227 East Bridgewater, Mass. 02333 USA [email protected] http://satucket.com Concerning the Service Christian marriage is a solemn and public covenant between a man and a woman in the presence of God. In the Episcopal Church it is required that one, at least, of the parties must be a baptized Christian; that the ceremony be attested by at least two witnesses; and that the marriage conform to the laws of the State and the canons of this Church. A priest or a bishop normally presides at the Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage, because such ministers alone have the function of pronouncing the nuptial blessing, and of celebrating the Holy Eucharist. -

Cornelia in Rome Lancaster.Pdf

CORNELIA AND ROME BEFORE WE BEGIN… •PLEASE KEEP IN MIND THAT •It is over 170 years since Cornelia first came to Rome •The Rome Cornelia visited was very different from the one that you are going to get to know whilst you are here •But you will be able to see and visit many places Cornelia knew and which she would still recognise WHAT WE ARE GOING TO DO •Learn a little bit about what Rome was like in the nineteenth century when Cornelia came •Look at the four visits Cornelia made to Rome in 1836-37, 1843-46, 1854, 1869 •Find out what was happening in Cornelia’s life during each visit ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY •It was a very small city with walls round it •You could walk right across it in two hours •Most houses were down by the river Tiber on the opposite bank from the Vatican •Inside the walls, as well as houses, there were vineyards and gardens, and many ruins from ancient Rome ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY •Some inhabitants (including some clergy) were very rich indeed, but the majority of people were very, very poor •The streets were narrow and cobbled and had no lighting, making them exremely dangerous once it went dark •The river Tiber often flooded the houses on its banks •Cholera epidemics were frequent ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY • You can see how overcrowded the city was when Cornelia knew it • There were magnificent palaces and church buildings but most people lived in wretchedly poor conditions • Injustice, violence and crime were part of everyday life ROME IN THE 19TH CENTURY • The river Tiber flowed right up against the houses • It -

The Constitution and the Statutes

The Constitution and the Statutes of the Swiss-American Benedictine Congregation Established by the General Chapter Changes Approved by CIVC – September 21, 2005 and summer 2008 Contents Preface Section I: Of the Nature and Purpose of the Congregation C 1-5 Section II: Norms for the Individual Monasteries A. Of the Organs of Government of the Monastery C 6-8; S 1-5 1. Of the Chapter C 9-10; S 6-10 2. Of the Abbot C 11-20; S 11-26 3. Of the Council C 21-23; S 27-29 4. Of Delegated Authority C 24-25; S 30-31 B. Of Order in the Community S 32-33 C. Of Claustral and Secular Oblates S 34-35 D. Of Novitiate and Profession, and of the Juniors C 26; S 36 1. Of the Novitiate C 27-31; S 37-41 2. Of Profession and the Temporarily Professed C 32-38; S 42-43 3. Of the Effects and Consequences of the Vows a. Stability, and Fidelity to the Monastic Way of Life C 39-42 b. Obedience C 43 c. Consecrated Celibacy C44 d. Poverty and the Sharing of Goods C 45-46; S 44-46 E. Of the Component Elements of Monastic Life 1. Of Common Prayer and the Common Life C 47-49; S 47-48 2. Of Private Prayer and Monastic Asceticism C 50-52; S 49 3. Of Work and Study C 53-54; S 50 4. Of Penalties and Appeals C 55-57; S 51-52 5. Of Financial Administration S 53-56 6. -

Hugh Taylor, a Carthusian Lay Brother

Watch" at dead of night, he saw a procession of angels Hugh Taylor, a in white raiment, each bearing a lighted candle in his hand. Entering the sacristy, they went straight to the carthusian Lay place in which the Sacristan had concealed the sacred particle. They bowed down in deepest adoration, brother opened the pyx, and after remaining some moments in contemplation of their Lord hidden in the Sacrament of Source: The Tablet – The International Catholic News weekly - Page His love to men, they vanished away. When morning 22, 16th March 1895 came, Brother Hugh asked the Sacristan if he had not placed the sacred particle he spoke of in that place. The The Catholic Truth Society has just published a short life answer being in the affirmative, Hugh told the story of of Dom Maurice Chauncy and Brother Hugh Taylor, his vision, and the Sacristan, fully assured by this grace, from the pen of Dom Lawrence Hendriks, of the same consumed the particle during his Mass; "neither," says order. Hugh Taylor was a Conversus, or professed lay Chauncy, "did he fear death, for he received the Author brother, distinguished by his virtues and by the evident of life, not sickness, for he received Him Who healeth all efficacy of his prayers; He entered the London our infirmities; nor did he any longer feel repugnance, Charterhouse in 1518. for he tasted in spirit that the Lord is sweet." Seculars Under the able direction of Prior Tynbygh, the holy were also in the habit of confiding their doubts and Irishman who formed the Carthusian Martyrs to difficulties to Brother Hugh. -

Memorial of St. Ignatius of Loyola the Year of St

1 Memorial of St. Ignatius of Loyola The Year of St. Ignatius of Loyola Remarks of Bishop John Barres St. Agnes Cathedral July 31, 2021 Father Stockdale, thank you for your inspiring homily and many thanks for the presence of your brother priests from Saint Anthony’s Church in Oceanside - Father John Crabb, S.J., and Father Peter Murray, S.J. Please express my gratitude and fraternal best wishes to Father Vincent Biaggi, S.J. and to your pastor Father James Donovan, S.J. Thank you to Father Daniel O’Brien, S.J., associate pastor of the shared parishes of Saint Martha, Uniondale and Queen of the Most Holy Rosary, Roosevelt for your presence here today. Together, Bishop William Murphy, Bishop Robert Coyle, Bishop Luis Romero, Fr. Bright, Fr. Herman, Fr. Alessandro da Luz, seminarian Louis Cona and I celebrate this historic moment with you, with our Holy Father Pope Francis, with Jesuits around the world, and with the People of God of the Diocese of Rockville Centre and the universal Church. It was in 1978 that Father Joseph Austin, S.J. arrived at Saint Anthony’s in Oceanside as a new pastor with two other members of the Society of Jesus.1 Our diocese and generations of Saint Anthony’s parishioners have been blessed by the spiritual charism and evangelizing spirit of the Society of Jesus. Founded by Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the Society of Jesus or “the Jesuits”, of which our Holy Father Pope Francis is a member, is the largest male religious order in the Catholic Church. -

The Value and Viability of the Jesuit Brother's Vocation

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/valueviabilityof404rehg <t> o 00 '£ 00 o o 00 o c 0> CO o 0? o a. 6 *-« o c c o/^ o X 3 CO > o o The Value and Viability of the Jesuit Brother's Vocation An American Perspective WILLIAM REHG, S J. 40/4 WINTER 2008 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. It concerns itself with topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially United States Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces through its publication, Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits. This is done in the spirit of Vatican II's recommendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the Unit- ed States. The issues treatecl may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, re- ligious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the journal, while meant especially for Ameri- can Jesuits, is not exclusively for them. Others who may find it helpful are cordially welcome to make use of it. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR R. Bentley Anderson, S.J., teaches history at St. Louis University, St. Louis, Mo. (2008) Richard A. Blake, S. J., is chairman of the Seminar and editor of Studies; he teaches film studies at Boston College, Chestnut Hill, Mass.