Jews and Unitarians Reform Faith and Architecture In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME INSTITUTION Borough of Manhattan Community

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 423 559 CS 509 903 TITLE New Media. INSTITUTION Borough of Manhattan Community Coll., New York, NY. Inst. for Business Trends Analysis. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 65p. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Downtown Business Quarterly; vl n3 Sum 1998 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Community Colleges; Curriculum Development; *Employment Patterns; Employment Statistics; Mass Media; *Technological Advancement; Technology Education; Two Year Colleges; *World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS City University of New York Manhattan Comm Coll; *New Media; *New York (New York) ABSTRACT This theme issue explores lower Manhattan's burgeoning "New Media" industry, a growing source of jobs in lower Manhattan. The first article, "New Media Manpower Issues" (Rodney Alexander), addresses manpower, training, and workforce demands faced by new media companies in New York City. The second article, "Case Study: Hiring Dynamid" (John Montanez), examines the experience of new employees at a new media company that creates corporate websites. The third article, "New Media @ BMCC" (Alice Cohen, Alberto Errera, and MeteKok), describes the Borough of Manhattan Community College's developing new media curriculum, and includes an interview with John Gilbert, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of Rudin Management, the company that transformed 55 Broad Street into the New York Information Technology Center. The fourth section "Downtown Data" (Xenia Von Lilien-Waldau) presents data in seven categories: employment, services and utilities, construction, transportation, real estate, and hotels and tourism. The fifth article, "Streetscape" (Anne Eliet) examines Newspaper Row, where Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph HearsL ran their empires. (RS) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force University of Texas at Austin April 2, 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Inputs to the Task Force ......................................................................................................... 6 Charge 1 ................................................................................................................................ 9 Offsite Storage, Cooperative Collection Management, and Print Preservation .................................9 Closure and Consolidation of Branch Libraries ............................................................................... 10 Redesign of Library Facilities Housing Academic and Research Collections ..................................... 10 Proliferation of Digital Resources and Hybrid Collections .............................................................. 11 Discovery Mechanisms ................................................................................................................. 12 Charge 2 .............................................................................................................................. 14 Size of the Fine Arts Library Collection .......................................................................................... 14 Use of the Fine Arts -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Isabel Amiano

isabel amiano www.isabelamiano.com.ar ARCHITECTURE NEW YORK New York in fact has three separately recognizable skylines: Midtown Manhattan, Downtown Manhattan (also known as Lower Manhattan), and Downtown Brooklyn. The largest of these skylines is in Midtown, which is the largest central business district in the world, and also home to such notable buildings as the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Center. The Downtown skyline comprises the third largest central business district in the United States (after Midtown and Chicago's Loop), and was once characterized by the presence of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Today it is undergoing the rapid reconstruction of Lower Manhattan, and will include the new One World Trade Center Freedom Tower, which will rise to a height of 1776 ft. when completed in 2010. The Downtown skyline will also be getting notable additions soon from such architects as Santiago Calatrava and Frank Gehry. Also, Goldman Sachs is building a 225 meter (750 feet) tall, 43 floor building across the street from the World Trade Center site. New York City has a long history of tall buildings. It has been home to 10 buildings that have held the world's tallest fully inhabitable building title at some point in history, although half have since been demolished. The first building to bring the world's tallest title to New York was the New York World Building, in 1890. Later, New York City was home to the world's tallest building for 75 continuous years, starting with the Park Row Building in 1899 and ending with 1 World Trade Center upon completion of the Sears Tower in 1974. -

Copyrighted Material

14_464333_bindex.qxd 10/13/05 2:09 PM Page 429 Index Abacus, 12, 29 Architectura, 130 Balustrades, 141 Sheraton, 331–332 Abbots Palace, 336 Architectural standards, 334 Baroque, 164 Victorian, 407–408 Académie de France, 284 Architectural style, 58 iron, 208 William and Mary, 220–221 Académie des Beaux-Arts, 334 Architectural treatises, Banquet, 132 Beeswax, use of, 8 Academy of Architecture Renaissance, 91–92 Banqueting House, 130 Bélanger, François-Joseph, 335, (France), 172, 283, 305, Architecture. See also Interior Barbet, Jean, 180, 205 337, 339, 343 384 architecture Baroque style, 152–153 Belton, 206 Academy of Fine Arts, 334 Egyptian, 3–8 characteristics of, 253 Belvoir Castle, 398 Act of Settlement, 247 Greek, 28–32 Barrel vault ceilings, 104, 176 Benches, Medieval, 85, 87 Adam, James, 305 interior, viii Bar tracery, 78 Beningbrough Hall, 196–198, Adam, John, 318 Neoclassic, 285 Bauhaus, 393 202, 205–206 Adam, Robert, viii, 196, 278, relationship to furniture Beam ceilings Bérain, Jean, 205, 226–227, 285, 304–305, 307, design, 83 Egyptian, 12–13 246 315–316, 321, 332 Renaissance, 91–92 Beamed ceilings Bergère, 240, 298 Adam furniture, 322–324 Architecture (de Vriese), 133 Baroque, 182 Bernini, Gianlorenzo, 155 Aedicular arrangements, 58 Architecture françoise (Blondel), Egyptian, 12-13 Bienséance, 244 Aeolians, 26–27 284 Renaissance, 104, 121, 133 Bishop’s Palace, 71 Age of Enlightenment, 283 Architrave-cornice, 260 Beams Black, Adam, 329 Age of Walnut, 210 Architrave moldings, 260 exposed, 81 Blenheim Palace, 197, 206 Aisle construction, Medieval, 73 Architraves, 29, 205 Medieval, 73, 75 Blicking Hall, 138–139 Akroter, 357 Arcuated construction, 46 Beard, Geoffrey, 206 Blind tracery, 84 Alae, 48 Armchairs. -

The Furness Memorial Library

3 The Furness Memorial Library Daniel Traister In memory of William E. Miller (1910-1994), Assistant Curator, Furness Memorial Library ilmarth S. Lewis, the great Horace Walpole collector, W once quipped that, if use were the criterion by which people judged the quality of libraries, we should judge that library to be the best which had the largest collection of telephone books. The Horace Howard Furness Memorial Library, now part of the Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania, has never needed to justify itself by denigrating “mere” use in favor of qual- ity and importance of collections. Over the years of its existence, it has always been among the most heavily used of Penn’s special collections (and this without even one telephone book in sight). The quality of its collections has never been in doubt, either. Its use is in part a reflection, obviously enough, of the drawing power of William Shakespeare. The Furnesses, father and son, based the collection on Shakespeare’s works and his stage and print career. Around these same topics their successors have continued to build it. The Furnesses’ chosen author has surely elicited more editions of and words about himself than any other writer in English—more, perhaps, than any other writer in the world. His continuing preeminence at all levels of education, and the popularity of Shakespearian productions on stage and screen, are evidence of an enthusiasm so widespread that it cannot be written off as merely academic. More than three hundred and fifty years after his death, Shakespeare continues to be box office. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Hamburg Historic District (amendment, increase, decrease) other names/site number Gold Coast 2. Location th hill to northwest of downtown: roughly W. 5 St from Western to N/A street & number Brown, W. 6th St from Harrison to Warren, W. 7th St from Ripley to not for publication th th Vine, W. 8 St from Ripley to Vine, W. 9 St from Ripley to Brown N/A city or town Davenport vicinity state Iowa code IA county Scott code 163 zip code 52802 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

How to Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture

How To Paint Black Furniture-A Dozen Examples Of Exceptional Black Painted Furniture frenchstyleauthority.com /archives/how-to-paint-black-furniture-a-dozen-examples-of-exceptional-black- painted-furniture Black furniture has been one of the most popular furniture paint colors in history, and a close second is white. Today, no other color comes close to these two basic colors which always seem to be a public favorite. No matter what the style is, black paint has been fashionable choice for French furniture,and also for primitive early American, regency and modern furniture. While the color of the furniture the same, the surrounds of these distinct styles are polar opposite requiring a different finish application. Early American furniture is often shown with distressing around the edges. Wear and tear is found surrounding the feet of the furniture, and commonly in the areas around the handles, and corners of the cabinets or commodes. It is common to see undertones of a different shade of paint. Red, burnt orange are common colors seen under furniture pieces. Furniture made from different woods, are often painted a color similar to wood color to disguise the fact that it was made from various woods. Paint during this time was quite thin, making it easily naturally distressed over time. – Black-painted Queen Anne Tilt-top Birdcage Tea Table $3,000 Connecticut, early 18th century, early surface of black paint over earlier red Joseph Spinale Furniture is one of the best examples to look at for painting ideas for early American furniture. This primitive farmhouse kitchen cupboard is heavily distressed with black paint. -

Faith Reforming

Reforming Faith by Design Frank Furness’ Architecture and Spiritual Pluralism among Philadelphia’s Jews and Unitarians Matthew F. Singer Philadelphia never saw anything like it. The strange structure took shape between 1868 and 1871 on the southeast corner of North Broad and Mount Vernon streets, in the middle of a developing residential neighborhood for a newly rising upper middle class. With it came a rather alien addition to the city’s skyline: a boldly striped onion dome capping an octagonal Moorish-style minaret that flared outward as it rose skyward. Moorish horseshoe arches crowned three front entrances. The massive central At North Broad and Mount Vernon streets, Rodeph Shalom’s first purpose-built temple—de- doorway was topped with a steep gable signed by Frank Furness—announced the growing presence and aspirations of the newly developed neighborhood’s prospering German Jewish community. beneath a Gothic rose window that, in HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA turn, sat within another Moorish horse- shoe. Composed of alternating bands of phia. In a city of red-brick rowhouses built full Jewish emancipation and equality and yellow and red sandstone, the arches’ halo- primarily in neoclassical styles, Rodeph sparked new spasms of anti-Semitism. like tops appeared to radiate from central Shalom’s new temple mixed Islamic, Pedestrians gazing upon Rodeph disks incised with abstracted floral shapes. Byzantine and Gothic elements. Shalom may have wondered whether their Buttresses shored the sides of the building, Founded in 1795 as the first Ashkenazi wandering minds conjured an appari- which stood tall and vertical like a Gothic (Central and Eastern European) Jewish tion from a faraway time and place. -

Subasta Octubre 2019

Subasta Octubre 2019 MITTWOCH 9 OKTOBER 2019 KL. 16:00 CEST (1 - 481) 1. LOMBARD SCHOOL. Gold reliquary medallion, late 16th 9. Jewellery set consisting of a brooch and earrings in gold, first Century - early 17th Century. half of the 19th Century. 18K gold, black enamel and central medallion depicting the Adoration of 14K gold, gilt metal and oval, round and square cut garnets, 1.80 cts the Shepherds on the front and the Flight to Egypt on the back, in approx. Brooch: 5.4x4.5 cm. Earrings: 4.3 cm. 20.5 gr. reverse-glass painting and églomisé. 4.8 x 3.8 cm. 31.8 gr. Schätzwert: 750 EUR Schätzwert: 550 EUR Endpreis: - Endpreis: 1.800 EUR 10. Catalan silver long earrings, 19th Century. 2. Two reliquary pendants, 17th-18th centuries. Silver, probably oval, cushion and pear cut topazes, 2.85 cts and rose One of them in the shape of Jerusalem Cross in silver and wood with cut diamonds, 0.25 cts approx. Original case included. 5.8 x 1.4 cm. mother of pearl inlays; and the other one as a medallion depicting Our 13.9 gr. Lady of Sorrows with the attributes of passion on the front and Saint Schätzwert: 300 EUR Margaret in an illuminated engraving on the back. 7.5x4.8 cm and 7x4.7 Endpreis: 650 EUR cm. 56.3 gr. Schätzwert: 550 EUR 11. Coral long earrings and bracelet, 19th Century. Endpreis: - 14K and 18K gold, coral beads, two flower-shaped coral beads, carved coral beads and coral cameo with the representation of a male bust. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

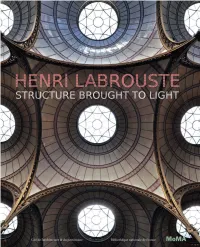

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Is the Condensed Result of Several Years of Research, Goers Are Plunged

HENRI LABROUSTE STRUCTURE BROUGHT TO LIGHT With essays by Martin Bressani, Marc Grignon, Marie-Hélène de La Mure, Neil Levine, Bertrand Lemoine, Sigrid de Jong, David Van Zanten, and Gérard Uniack The Museum of Modern Art, New York In association with the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine et the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the special participation of the Académie d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This exhibition, the first the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine has devoted to Since its foundation eighty years ago, MoMA’s Department of Architecture (today the a nineteenth-century architect, is part of a larger series of monographs dedicated Department of Architecture and Design) has shared the Museum’s linked missions of to renowned architects, from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau to Claude Parent and showcasing cutting-edge artistic work in all media and exploring the longer prehistory of Christian de Portzamparc. the artistic present. In 1932, for instance, no sooner had Philip Johnson, Henry-Russell Presenting Henri Labrouste at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine carries with Hitchcock, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., installed the Department’s legendary inaugural show, it its very own significance, given that his name and ideas crossed paths with our insti- Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, than plans were afoot for a show the following tution’s history, and his works are a testament to the values he defended. In 1858, he year on the commercial architecture of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, intended as the even sketched out a plan for reconstructing the Ecole Polytechnique on Chaillot hill, first in a series of shows tracing key episodes in the development of modern architecture though it would never be followed through.