Police Body-Worn Cameras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attachment Council Agenda Bill I

Item: NB #5 City of Arlington Attachment Council Agenda Bill I COUNCIL MEETING DATE: July 6, 2020 SUBJECT: Community Policing, Policy and Accountability ATTACHMENTS: DEPARTMENT OF ORIGIN Presentation, Org Chart, IAPRO, BlueTeam, 2018 Strategic Planning, APD Planning Recommendations Police; Jonathan Ventura, Chief and Human Resources; James Trefry, Administrative Services Director EXPENDITURES REQUESTED: None BUDGET CATEGORY: N/A BUDGETED AMOUNT: 0 LEGAL REVIEW: DESCRIPTION: Presentation by the Chief of Police and the Administrative Services Director regarding the Arlington Police Department. Topics covered include community policing, policy and accountability. HISTORY: The Mayor and Councilmembers have requested a presentation about the current state of the police department in light of current events and feedback received from the community. ALTERNATIVES: Remand to staff for further information. RECOMMENDED MOTION: Information only; no action required. Arlington Police Department COMMUNITY POLICING / POLICY / ACCOUNTABILITY Community Policing Community Outreach Team / LE Embedded Social Worker (LEESW) (2018) Domestic Violence Coordinator (2019) School Resource Officer All-In Program / Conversations with Cops COP’s Building Trust Grant – Funding for 2 Officers (2015) Boards and Commissions Community Meetings 21st Century Policing Initiative Strategic Plan (2018) Virtual Training Simulator (2019) Crime Data (2019) Traffic Enforcement up 32% DUI Enforcement up 14% Burglary reports down 15% Robbery reports down 38% Overall Theft Reporting -

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale Proceeds by Recipient Agency for California

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale Proceeds by Recipient Agency for California Fiscal Year 2016 Agency Name Agency Type Cash Value Sales Proceeds Totals Alameda County District Attorney's Office Local $10,996 $0 $10,996 Alameda County Narcotics Task Force Task Force $0 $84,324 $84,324 Alameda County Sheriff's Office Local $11,152 $0 $11,152 Alhambra Police Department Local $351,211 $0 $351,211 Anaheim Police Department Local $1,524,643 $0 $1,524,643 Arcadia Police Department Local $0 $51 $51 Azusa Police Department Local $519,313 $0 $519,313 Bakersfield Police Department Local $24,010 $9,236 $33,246 Bell Gardens Police Department Local $828,834 $0 $828,834 Butte County District Attorney Local $23,843 $41,259 $65,102 Butte County Sheriff's Office Local $146,314 $141,022 $287,336 Butte Interagency Narcotics Task Force (BINTF) Task Force $20,589 $80,066 $100,655 California Department Of Corrections And Rehabilitation State $80,402 $67,244 $147,646 California Department Of Justice (DOJ) - Division Of Law Enforcement State $156,871 $16,227 $173,098 Chula Vista Police Department Local $112,258 $2,000 $114,258 Citrus Heights Police Department Local $3,143 $7,895 $11,038 City Of Baldwin Park Police Department Local $134,442 $1,764 $136,206 City Of Beverly Hills Police Department Local $527,882 $17,540 $545,422 City Of Brawley Police Department Local $26,539 $0 $26,539 City Of Carlsbad Police Department Local $48,291 $2,000 $50,291 City Of Chino Police Department Local $149,103 $1,725 $150,828 City Of Coronado Police Department Local $48,291 -

POST Law Enforcement K-9 Guidelines

K-9 Teams Detection Training Services C20K0001 Attachment - 2 POST Law Enforcement K-9 Guidelines CALIFORNIA COMMISSION ON PEACE OFFICER STANDARDS AND TRAINING POST Law Enforcement K-9 Guidelines Produced by POST Training Program Services Bureau Foreword by Robert A. Stresak POST Executive Director POST Law Enforcement K-9 Guidelines ©2014 by California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training Published January 2014 All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical or by any information retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without prior written permission of the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, with the following exception: California law enforcement agencies in the POST peace officer program and POST-certified training presenters are hereby given permission by POST to reproduce any or all of the contents of this manual for their internal use. All other individuals, private businesses and corporations, public and private agencies and colleges, professional associations, and non-POST law enforcement agencies in state or out-of-state may print or download this information for their personal use only. Infringement of the copyright protection law and the provisions expressed here and on the POST website under Copyright/Trademark Protection will be pursued in a court of law. Questions about copyright protection of this publication and exceptions may be directed to Publications Manager. All photos used with permission. Special thanks to Chief David M. Brown, Hemet Police Department. POST2014TPS-0414 POST Mission Statement The mission of the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training is to continually enhance the professionalism of California law enforcement in serving its communities. -

Employment Data for California Law Enforcement 1991/92

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. EMPLOYMENT DATA FOR CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT 1991/92 - 1992/93 145590 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the p~rson or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated in this do.c~ment ~~e those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the offiCial position or pOlicies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by California Commission on Peace Officer Standards & Training to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further rep~duction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyrrght owner . • • EMPLOYMENT DATA FOR 0, CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT 1991/92 - 1992/93 • State of California Department of Justice Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training Information Services Bureau 1601 Alhambra Boulevard Sacramento, CA 95816-7083 @ Copyrighl 1993. California Commission on '. Peace 0fIi= Standards and Training .---------- Commission on Peace OMcer Standards and Training ---------........ • COMMISSIONERS Sherman Block Sheriff ., Chairman Los Angeles County Marcel L. Leduc Sergeant Vice-Chairman San Joaquin Co. Sheriffs Department Colleue Campbell Public Member Jody Hall-Esser Chief Administrative Officer City of Culver City Edward Hunt District Attorney Fresno County Ronald Lowenberg Chief of Police Huntington Beach Daniel E. Lungren Attorney General • Ex-Officio Member Raquel Montenegro Professor of Education C.S.U.LA. Manuel Ortega Chief of Police Placentia Police Dept. Bernard C. Parks Assistant Chief Los Angeles Police Dept. Devallis Rutledge Deputy District Attorney Orange County D. -

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale Proceeds by Recipient Agency Fiscal Year 2017

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale Proceeds by Recipient Agency Fiscal Year 2017 Alabama Agency Name Agency Type Cash Value Sales Proceeds Totals 32nd Circuit - Cullman District Attorney Local $8,425 $0 $8,425 Athens Police Department Local $3,130 $0 $3,130 Auburn City Police Department Local $17,519 $1,114 $18,633 Autauga County Sheriff's Office Local $24,518 $1,114 $25,632 Baldwin County Sheriff's Office Local $413,153 $0 $413,153 Bessemer Police Department Local $176,024 $3,901 $179,925 Birmingham Police Department Local $46,396 $3,901 $50,297 Blount County Sheriff's Office Local $8,282 $0 $8,282 Calera Police Department Local $15,528 $2,201 $17,729 Calhoun Cleburne County Drug And Violent Crime Task Force Task Force $9,533 $2,113 $11,646 Central Alabama Drug Task Force Task Force $32,662 $1,393 $34,055 City Of Hoover Police Department Local $177,430 $3,901 $181,331 City Of Montevallo Police Department Local $8,425 $0 $8,425 City Of Montgomery Police Department Local $132,788 $10,988 $143,776 City Of Troy Police Department Local $2,192 $0 $2,192 Cullman County Sheriff's Office Local $3,567 $2,349 $5,916 Decatur Police Department Local $0 $1,944 $1,944 Dothan Police Department Local $26,789 $10,034 $36,823 Elmore County Sheriff's Department Local $21,117 $279 $21,396 Eufaula Police Department Local $5,040 $0 $5,040 Fairfield Police Department Local $25,143 $5,876 $31,019 Foley Police Department Local $8,275 $0 $8,275 Gardendale Police Department Local $5,385 $3,901 $9,286 Huntsville - Madison - Morgan County Strategic Counterdrug -

Applicant Rankings by State

Applicant Rankings by State *For additional information on the creation of these indices please see www.cops.usdoj.gov/Default.asp?Item=2208 **Note that this list contains 7,202 agencies. There were 58 agencies that were found to be ineligible for funding and 12 that withdrew after submitting applications, for a total of 7,272 applications received. Crime and Crime and Fiscal Need Community Final Index: Community Index: 0-50 Policing Index: 0- 0-100 Fiscal Need Policing Possible 50 Possible Possible Index Index Final Index State ORI Agency Name Points Points Points Percentile Percentile Percentile Akiachak Native Community Police AK AK002ZZ Department 31.20 36.75 67.95 99.9% 91.6% 99.9% AK AK085ZZ Tuluksak Native Community 21.18 39.44 60.62 98.5% 95.6% 99.2% AK AK038ZZ Akiak Native Community 18.85 38.40 57.25 96.7% 94.5% 98.0% AK AK033ZZ Manokotak, Village of 20.66 35.68 56.35 98.3% 89.4% 97.5% AK AK065ZZ Anvik Tribal Council 20.53 34.91 55.44 98.2% 87.6% 97.0% AK AK090ZZ Native Village of Kotlik 11.10 43.90 54.99 52.1% 98.9% 96.6% AK AK062ZZ Atmautluak Traditional Council 21.26 33.06 54.31 98.6% 82.7% 96.0% AK AK008ZZ Kwethluk, Organized Village of 25.85 25.97 51.82 99.7% 56.9% 93.8% AK AK057ZZ Gambell Police Department 20.37 30.93 51.30 98.1% 76.2% 93.0% AK AK095ZZ Alakanuk Tribal Council 22.18 26.44 48.61 99.0% 58.8% 89.4% AK AK00109 Sitka, City and Borough of 10.48 37.16 47.64 44.1% 92.3% 87.5% AK AK00102 Fairbank Department of Public Safety 11.64 35.25 46.89 58.8% 88.5% 85.8% AK AK00115 Yakutat Department of Public Safety 8.16 38.39 46.56 15.2% 94.5% 85.1% AK AK00101 Anchorage Police Department 13.52 31.27 44.79 77.3% 77.2% 80.7% AK AK00107 Petersburg Police Department 9.70 32.48 42.18 32.8% 81.3% 73.4% AK AK123ZZ Native Village of Napakiak 14.49 25.32 39.81 84.1% 54.2% 66.1% AK AK119ZZ City of Mekoryuk 12.65 26.94 39.59 69.7% 61.0% 65.4% Klawock Department of Public AK AK00135 Safety/Police Dept. -

Charles. Leslie Alabaster Police Department 201 1St Street North

Charles. Leslie Alabaster Police Department 201 1st Street North Alabaster, Alabama 35007 205- 664-6817 [email protected] Charles W. Wood Calhoun County Sheriff's Office 400 West 8th Street Anniston, Alabama 36201 (256) 820-6710 [email protected] Capt. Tom Stofer Auburn Department of Public Safety 161 North Ross Street Auburn, Alabama 36830 334-501- 3119 [email protected] La'Quaylin Parhm or Damon Johnson Birmingham Police Department 1710 First Avenue North Birmingham, Alabama 35203 (205) 933-4175 [email protected] James G. Fadely Jefferson County Sheriff's Office Reserves 2200 8th Avenue North Birmingham, Alabama 35203 205- 325-5700 [email protected] Robert Burnett Chelsea Citizen Observer Patrol City of Chelsea P.O. Box 111 Chelsea, Alabama 35043 205-281- 4082 [email protected] Officer David Hicks Clanton Police Department Police Explorers 601 1st Ave. Clanton, Alabama 35045 (205) 755-1194 [email protected] Jim Smith Police Chief Cottonwood Police Department P. O. Box 447 Cottonwood, Alabama 36320 334- 691-2113 [email protected] Capt. David J. Sandlin Cullman County Sheriff's Office 1910 Beech Avenue, S.E. Cullman, Alabama 35055 256-734- 0342 [email protected] Tom Barry Decatur Citizens Police Academy Alumni Association P O Box 5581 Decatur, Alabama 35601 256-301- 3139 [email protected] Tommie J. Reese, Chief of Police Demopolis Police Department 301 East Washington Street Demopolis, Alabama 36732 334- 289-3073 [email protected] Samuel Crawford Wiregrass Retired Senior Volunteer Program 501 North Foster St. Dothan, Alabama 36303 334-836- 1300 [email protected] Alan Hicks, Asst. Chief Douglas Police Reserves P. -

Office of Criminal Justice Planning Sacramento, CA 95814 1130 K Street, Suite 300 (916) 551-1063 Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 327-8704 Andrew L

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ~-===-~I ! 147229 Cal'lIornia - o.cf' Justice rl annlngL,lce of Cri mlnal' OFFICE OF CRIMINAL ~ ... .... i . .. USTICEP.............. LANNING \ ~UNE1882 : • FORTS TABLE OF CONTENTS STA1EWIDE ANTI-GANG EFFORTS ..................•........................................................... 1 ALA:tvmD A COUNTY ........................................................................ II" II ..••••.•.••...•.••. e8........ 2 CON1RA COSTA COUNTY ............... ............ ........ .................................... ........................ 3 FRESNO COUNIT ....................................... 1;1 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 0. •••••• 4 HUMBOLDT COUNTY ....................................................................................................... 4 Il\t1PERIAL COUNTY ......... "....................... 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• C/ •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 5 KERN CO UNf'Y ............................... ................................................................................... 5 • KrnGS COUNTY ................................................. "............................................................... 6 LA.KE COUN1Y ........................................... e ............................................................................ 6 LOS ANGELES eoUNIT' ................................ 5 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 MARIN' COUNTY ..................................................................................................................... -

2020 Named Freeway Publication

Photograph taken by Caltrans Photography 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California Prepared by The California Department of Transportation © 2021 California Department of Transportation. All Rights Reserved. [page left intentionally blank] 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California STATE OF CALIFORNIA Gavin Newsom, Governor CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY David S. Kim, Secretary CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Toks Omishakin, Director CALTRANS DIVISION OF RESEARCH, INNOVATION and SYSTEM INFORMATION Office of Highway System Information and Performance January 2021 [page left intentionally blank] PREFACE 2020 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California is produced by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) as a reference on the many named facilities that are a part of the California State Highway System. This publication provides information on officially named freeways; highways; structures such as bridges, tunnels, and interchanges; Blue Star Memorial Highways; Safety Roadside Rest Areas; and memorial plaques. A section concerning historical names is also included in this publication. The final section of this publication includes background information on each naming. HOW FREEWAYS, HIGHWAYS AND STRUCTURES ARE NAMED Each route in the State Highway System is given a unique number for identification and signed with distinctive numbered Interstate, United States, or California State route shields to guide public travel. The State Legislature designates all State highway routes and assigns route numbers, while the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) has authority over the numbering of Interstate and United States routes. In addition to having a route number, a route may also have a name and, in some cases, multiple names. -

A Report on Body Worn Cameras

A REPORT ON BODY WORN CAMERAS BY EUGENE P. RAMIREZ1 Manning & Kass, Ellrod, Ramirez, Trester LLP 15th Floor at 801 Tower 801 South Figueroa Street Los Angeles, California 90017 213‐624‐6900 CONTENTS BODY WORN CAMERAS .............................................................................................................................. 3 CALIFORNIA: THE TWO‐PARTY CONSENT STATE ........................................................................................ 5 THE RIALTO STUDY ...................................................................................................................................... 6 THE ACLU’S REPORT ON BODY WORN CAMERAS ..................................................................................... 11 POLICE EXECUTIVE RESEARCH FORUM’S STUDY ...................................................................................... 13 THE ACLU & PRIVACY RIGHTS ................................................................................................................... 15 ACLU RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................................................................... 16 ARE THERE EXEMPTIONS TO WEARING A BODY WORN CAMERA? .......................................................... 19 IN SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ 20 ENDNOTES ............................................................................................................................................... -

Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program Recommendations and Lessons Learned Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program Recommendations and Lessons Learned This project was supported by cooperative agreement number 2012-CK-WX-K028 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the author(s) or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of publication. Given that URLs and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s) nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. The points of view expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions of individual Police Executive Research Forum members. Recommended citation: Miller, Lindsay, Jessica Toliver, and Police Executive Research Forum. 2014. Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. ISBN: 978-1-934485-26-2 Published 2014 Contents Letter from the PERF Executive Director . v Letter from the COPS Office Director . vii Acknowledgments . ix. Introduction . 1 State of the field and policy analysis . 1 Project overview . 2 Chapter 1 . Perceived Benefits of Body-Worn Cameras . 5 Accountability and transparency . 5 Reducing complaints and resolving officer-involved incidents . 5 Identifying and correcting internal agency problems . -

Case 6:12-Bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27

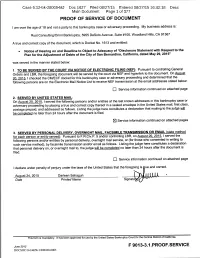

Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 377 Case 6:12-bk-28006-MJ Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 377 City of San BernardinoCase 6:12-bk-28006-MJ - U.S. Mail Doc 1627 Filed 08/27/15 Entered 08/27/15 16:42:18 DescServed 8/20/2015 Main Document Page 3 of 377 @COMM DEPARTMENT 05321 100 PLAZA CLINICAL LAB INC 1458 - CELPLAN TECHNOLOGIES, INC. P O BOX 39000 100 UCLA MEDICAL PL 245 1920 ASSOCIATION DRIVE, 4TH FLOOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94139-5321 LOS ANGELES, CA 90024-6970 RESTON, VA 20191 3M CUSTOMER SERVICE A & G TOWING A & R LABORATORIES INC 2807 PAYSPHERE CIR 591 E 9TH ST 1401 RESEARCH PARK DR 100 CHICAGO, IL 60674 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410 RIVERSIDE, CA 92507 A & W EMBROIDERY A 1 AUTO GLASS A 1 BUDGET GLASS P O BOX 10926 671 VALLEY BL 705 S WATERMAN AV SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92423 COLTON, CA 92324 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 A 1 BUDGET HOME & OFFICE CLEANING A 1 EVENT & PARTY RENTALS A 1 TREE SERVICE 2889 N GARDENA ST 251 E FRONT ST 304 E CLARK SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92407-6633 CORONA, CA 91723 REDLANDS, CA 92373 A A EQUIPMENT RENTAL A AMERICAN SELF STORAGE A G ENGINEERING 4811 BROOKS ST 875 E MILL ST 8647 HELMS AV MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 RANCHO CUCAMONGA, CA 91730 A GRAPHIC ADVANTAGE A J JEWELRY A J O CONNOR LADDER 3901 CARTER AV 2 1292 W MILL ST 103 4570 BROOKS RIVERSIDE, CA 92501 SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92410-2500 MONTCLAIR, CA 91763 A K ENGINEERING A L WARD A PLUS AUTOMOTIVE INC 1254 S WATERMAN AV 17 ADDRESS REDACTED A PLUS SMOG AND MUFFLER SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92408 235 E HIGHLAND SAN BERNARDINO, CA 92404 A PLUS COURT REPORTERS INC A T & T A T S I 35 E UNION ST A 1265 VAN BUREN 180 8157 US HIGHWAY 50 PASADENA, CA 91103 ANAHEIM, CA 92807 ATHENS, OH 45701 A T SOLUTIONS INC A T SOLUTIONS INC.