Afriheritage Research Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Download File

CAMEROON: COVID-19 Situation Report – #13 13 June – 25 June 2020 Situation Overview and Humanitarian Needs As of 25 June 2020, there have been over 12,825 confirmed COVID-19 cases, with 7,774 recoveries and 331 deaths (fatality rate: 2.6%). Cases have been reported in all ten regions of the country though the majority remain in Central and Littoral regions. The crisis Situation in Numbers is accelerating. During the period 1-25 June, the number of cases has nearly doubled from 6,752. 12,825 COVID- UNICEF continues to assist the Government response as the sector co-lead for the Risk 19 confirmed Communications and Community Engagement (RCCE) pillar, particularly addressing the cases growing stigma faced by infected persons. In view of the accelerating rate of transmissions in regions with pre-existing humanitarian 331 deaths needs, especially North-West, South-West, Far North, North, East and Adamaoua regions, UNICEF has adjusted its 2020 humanitarian funding requirements, reflected in 5,800,000 the country inter-agency Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), launched on 24 June. The Children affected revised HRP/HNO estimates that 6.2 million people including 3.2 million children are in need. UNICEF COVID-19 activities are also included in UNICEF’s global COVID-19 HAC by COVID-19 appeal, launched on 11 May. school closures UNICEF continues advocacy for the prevention of children detention while supporting COVID-19 sensitisation for children and their caregivers in situations of detention. In US$ 24 M major urban centres, UNICEF has developed responses for street children and ensuring funding required of safe sanitary and protection environments in childcare facilities for separated and isolated which $5.3m children. -

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N'djida

Aerial Surveys of Wildlife and Human Activity Across the Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape Northern Cameroon and Southwestern Chad April - May 2015 Paul Elkan, Roger Fotso, Chris Hamley, Soqui Mendiguetti, Paul Bour, Vailia Nguertou Alexandre, Iyah Ndjidda Emmanuel, Mbamba Jean Paul, Emmanuel Vounserbo, Etienne Bemadjim, Hensel Fopa Kueteyem and Kenmoe Georges Aime Wildlife Conservation Society Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) L'Ecole de Faune de Garoua Funded by the Great Elephant Census Paul G. Allen Foundation and WCS SUMMARY The Bouba N’djida - Sena Oura - Benoue - Faro Landscape is located in north Cameroon and extends into southwest Chad. It consists of Bouba N’djida, Sena Oura, Benoue and Faro National Parks, in addition to 25 safari hunting zones. Along with Zakouma NP in Chad and Waza NP in the Far North of Cameroon, the landscape represents one of the most important areas for savanna elephant conservation remaining in Central Africa. Aerial wildlife surveys in the landscape were first undertaken in 1977 by Van Lavieren and Esser (1979) focusing only on Bouba N’djida NP. They documented a population of 232 elephants in the park. After a long period with no systematic aerial surveys across the area, Omondi et al (2008) produced a minimum count of 525 elephants for the entire landscape. This included 450 that were counted in Bouba N’djida NP and its adjacent safari hunting zones. The survey also documented a high richness and abundance of other large mammals in the Bouba N’djida NP area, and to the southeast of Faro NP. In the period since 2010, a number of large-scale elephant poaching incidents have taken place in Bouba N’djida NP. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview

1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies Contents occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 71 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Humanitarian crisis in Niger 3 - 6 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Central African Republic 7 Summary of major issues, challenges Cholera in Burundi. and proposed actions For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 8 All events currently being monitored A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as recent events that have largely been controlled and thus closed. Major issues and challenges include: The humanitarian crisis in Niger and the Central African Republic remains unabated, characterized by continued armed attacks, mass displacement of the population, food insecurity, and limited access to healthcare services. In Niger, the extremely volatile security situation along the borders with Burkina Faso, Mali, and Nigeria occasioned by armed attacks from Non-State Actors as well as resurgence in inter-communal conflicts, is contributing to an unprecedented mass displacement of the population along with its associated consequences. Seasonal flooding with huge impact as well as high morbidity and mortality rates from common infectious diseases have also complicated response to the humanitarian crisis. -

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°143 Nairobi /Brussels, 14 January 2019 What’s new? Protests across Sudan flared up as the government cut a vital bread subsidy. Economic grievances are fuelling demands for political change, with protest- ers calling on President Omar al-Bashir, in power since 1989, to resign. Authorities have responded with violence, killing dozens and arresting many more. Why does it matter? In the past, President Bashir and his government have been able to ride out popular demonstrations. But these newest protests, demanding Bashir resign because of economic mismanagement and corruption, have spread to loyalist regions and coincide with rising discontent in his party. What should be done? Foreign governments influential in Khartoum should continue to publicly discourage violence against demonstrators, with Western pow- ers signalling that future aid and, in the U.S.’s case, sanctions relief are at stake. They should seek to improve prospects for a peaceful transition by creating incentives for Bashir to step down. I. Overview Protests engulfing Sudanese towns and cities have seen dozens killed in crackdowns by security forces and could turn bloodier still. Demonstrators express fury over sub- sidy cuts and call for President Omar al-Bashir to resign. Discontent within the ruling party, the depth of the economic crisis and the diverse makeup of protests suggest Bashir has less room to manoeuvre than before. He may survive, though likely by suppressing protests with levels of violence that would reverse his recent rapproche- ment with Western powers and deepen Sudan’s economic woes. -

MINMAP South-West Region

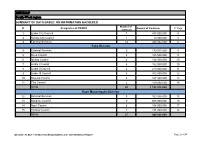

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon

sustainability Article Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon Akhere Solange Gwan 1 and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi 2,3,* 1 Department of Geography and Planning, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Technische Universität Dresden, 01737 Tharandt, Germany 3 Department of Geography, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 14 July 2020; Published: 18 July 2020 Abstract: There is growing interest in the need to understand the link between urban expansion and farmers’ livelihoods in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including Cameroon. This paper undertakes a qualitative investigation of the effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods in Bamenda, a primate city in Cameroon. Taking into consideration two key areas—the Mankon–Bafut axis and the Nkwen Bambui axis—this study analyzes the trends and effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods with a view to identifying ways of making the process more beneficial to the farmers. Maps were used to determine the trend of urban expansion between 2000 and 2015. Twelve farmers drawn from the target sites were interviewed, while three focus group discussions were conducted. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze perceptions of the effects and coping strategies of farmers to urban expansion. Using the livelihoods approach, farmers’ livelihoods repertoires and portfolios were analyzed for the periods before and after urban expansion. Between 2000 and 2015, the surface area for farmlands in Bamenda II and Bamenda III reduced from 3540 ha to 2100 ha and 2943 ha to 1389 ha, respectively. -

MINMAP South-West Region

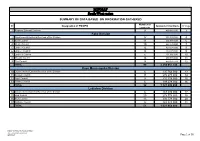

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon

Centre for Research on Settlements and Urbanism Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning J o u r n a l h o m e p a g e: http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon Lawrence Akei MBANGA 1 1 The University of Bamenda, Faculty of Arts, Department of Geography and Planning, Bamenda, CAMEROON E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 https://doi.org/10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 K e y w o r d s: human settlements, dynamics, sustainability, Bamenda III, Cameroon A B S T R A C T Every human settlement, from its occupation by a pioneer population continues to undergo a process of dynamism which is the result of socio economic and dynamic factors operating at the local, national and global levels. The urban metabolism model shows clearly that human settlements are the quality outputs of the transformation of inputs by an urban area through a metabolic process. This study seeks to bring to focus the drivers of human settlement dynamics in Bamenda 3, the manifestation of the dynamics and the functional evolution. The study made used of secondary data and information from published and unpublished sources. Landsat images of 1989, 1999 and 2015 were used to analyze dynamics in human settlement. Field survey was carried out. The results show multiple drivers of human settlement dynamism associated with population growth. Human settlement dynamics from 1989, 1999 and 2015 show an evolution in surface area with that of other uses like agriculture reducing.