The Age of Reform: a Defense of Richard Hofstadter Fifty Years On* , Subject to the Cambridge Core Terms of Use, Available At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science *

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science * George REISCH Received: 31.5.2012 Final version: 30.7.2012 BIBLID [0495-4548 (2012) 27: 75; pp. 323-342] ABSTRACT: Historian Richard Hofstadter’s observations about American cold-war politics are used to contextualize Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and argue that substantive claims about the nature of sci- entific knowledge and scientific change found in Structure were adopted from this cold-war political cul- ture. Keywords: Thomas S. Kuhn; The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics;” Cold War; James B. Conant; Brainwashing. RESUMEN: Las observaciones del historiador Richard Hofstadter sobre la política americana en la Guerra Fría se uti- lizan para contextualizar La estructura de las revoluciones científicas de Thomas Kuhn y sostener que algunas afirmaciones fundamentales sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento científico y el cambio científico que se pueden hallar en La estructura fueron adoptadas de esta cultura política de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave: Thomas S. Kuhn; La estructura de las revoluciones científicas ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”; Guerra Fría; James B. Conant; lavado de cerebro. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant. –Richard Hofstadter (1964, 4) 1. Introduction The conventional wisdom holds that Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions of- fered a revolutionary critique of existing scholarship about science. The book swept aside misconceptions wrought by three kinds of intellectuals—logic-chopping philos- ophers who confused their logical models and formulas with historical fact, Whiggish historians who viewed science’s past through the lenses of the present, and text-book writers whose brief, potted historical introductions obscured science’s dynamic, revo- lutionary history. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott

University of New England DUNE: DigitalUNE All Theses And Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2017 Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SU A: Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott Austin Coco University of New England Follow this and additional works at: http://dune.une.edu/theses Part of the Political Science Commons © 2017 Austin Coco Preferred Citation Coco, Austin, "Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SAU : Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott" (2017). All Theses And Dissertations. 136. http://dune.une.edu/theses/136 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at DUNE: DigitalUNE. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses And Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DUNE: DigitalUNE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Austin Coco Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Austin Coco Coco|1 Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Introduction This essay examines three cases of otherness: the Italian other in the 1920s, the Communist other during the Red Scare of the 1950s, and the Muslim other in post-2001. The similarities and differences of these cases will be analyzed through Richard Hofstadter’s analysis of the production of otherness for what he calls the paranoid style, Foucault’s analysis of power relations, and James Scott’s analysis of power relations and language. This essay will assess the theoretical methods behind “otherness” that Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott use, the three cases of “otherness”, and the similarities and differences between the cases and how the theoretical mechanisms apply. -

What Kind of Book Is the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution?

What Kind of Book is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution? eric nelson first read Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the I American Revolution when I was a nineteen-year-old stu- dent in the Harvard History Department’s sophomore tutorial. The text was assigned by my late friend and teacher Mark Kish- lansky, who began our discussion of the book by posing the same deceptively simple question that he asked about each his- toriographical masterwork on the syllabus: “What kind of book is this?” I remember thinking rather smugly that, in this case at least, the question had an obvious and straightforward answer: surely, Ideological Origins was a work of intellectual history— and, more specifically, a contribution to the history of early American political thought. But it now strikes me that this an- swer, while not incorrect, was, and is, quite beside the point. Mark was not asking us a banal question about the genre to which Bailyn’s monograph belonged, but rather a deep one about how Bailyn understood that genre. To present Ideological Origins as a history of political thought is, implicitly, to defend a particular conception of what sort of thing “political thought” is and what its history looks like. What, Mark wished us to pon- der, is that conception? I found myself asking this question with a renewed sense of urgency more than fifteen years later as I grappled witha I am indebted to Bernard Bailyn, Richard Bourke, Jonathan Gienapp, James Hank- ins, Michael Rosen, and Quentin Skinner for extremely helpful comments on this essay. -

The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption

The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption Foreword by Chester E. Finn, Jr. Introduction by Diane Ravitch 1627 K Street Northwest Suite 600 Washington D.C. 20006 (202) 223-5452 (202) 223-9226 Fax www.edexcellence.net September 2004 The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts research, issues publications, and directs action projects in elementary/secondary education reform at the national level and in Dayton, Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Further information is at www.edexcellence.net/institute, or write us at 1627 K Street Northwest Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20006 This report is available in full on the web site. Additional copies can be ordered at www.edexcellence.net/institute/publication/order.cfm or by calling 410-634-2400. The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University. Cover illustration by Thomas Fluharty, all rights reserved Design by Katherine Rybak Torres, all rights reserved Printed by District Creative Printing, Upper Marlboro, Maryland Executive Summary extbook Adoption: The process, in place in twenty-one states, of Treviewing textbooks according to state guidelines and then man- dating specific books that schools must use, or lists of approved text- books that schools must choose from. Textbook Adoption Is Bad for Students and Schools It consistently produces second-rate textbooks that replicate the same flaws and failings over and over again. Adoption states perform poorly on national tests, and the market incentives caused by the adop- tion process are so skewed that lively writing and top-flight scholarship are discouraged. -

Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism

The Rot at the Heart of American Progressivism: Imperialism, Racism, and Fear of Democracy in Richard Ely's Progressivism Gerald Friedman Department of Economics University of Massachusetts at Amherst November 8, 2015 This is a sketch of my long overdue intellectual biography of Richard Ely. It has been way too long in the making and I have accumulated many more debts than I can acknowledge here. In particular, I am grateful to Katherine Auspitz, James Boyce, Bruce Laurie, Tami Ohler, and Jean-Christian Vinel, and seminar participants at Bard, Paris IV, Paris VII, and the Five College Social History Workshop. I am grateful for research assistance from Daniel McDonald. James Boyce suggested that if I really wanted to write this book then I would have done it already. And Debbie Jacobson encouraged me to prioritize so that I could get it done. 1 The Ely problem and the problem of American progressivism The problem of American Exceptionalism arose in the puzzle of the American progressive movement.1 In the wake of the Revolution, Civil War, Emancipation, and radical Reconstruction, no one would have characterized the United States as a conservative polity. The new Republican party took the United States through bloody war to establish a national government that distributed property to settlers, established a national fiat currency and banking system, a progressive income tax, extensive program of internal improvements and nationally- funded education, and enacted constitutional amendments establishing national citizenship and voting rights for all men, and the uncompensated emancipation of the slave with the abolition of a social system that had dominated a large part of the country.2 Nor were they done. -

Uncovering the Reformation Roots of American Marriage and Divorce Law

Uncovering the Reformation Roots of American Marriage and Divorce Law Judith Areent INTRO D UCTIO N ............................................................................................... 30 I. SIXTEENTH CENTURY EUROPEAN MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE LAW R EFO R M .............................................................................................. 34 A. Luther Advocates Civil Marriage and Fault-Based Divorce .......... 35 B. Zwingli Inspires Zurich to Enact the First Modem Marriage and D ivorce Law ....................................................................... 44 C. Calvin's Geneva Adopts a Civil Marriage and Divorce O rdinance .................................................................................. 49 II. REFORMATION IN ENGLAND ............................................................... 53 A. Henry VIII Opposes Divorce ..................................................... 53 B. Archbishop Cranmer Proposes the Reformatio Legum Ecclesiasticarum....................................................................... 54 C. The Rise of Godly Puritans and Support for Marriage and D ivorce Reform ......................................................................... 59 III. MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE LAW IN COLONIAL AMERICA .................... 61 A. Civil Marriage in Plymouth Plantation ...................................... 61 B. Civil Marriage and Divorce in Massachusetts Bay Colony ........... 64 C. Civil Marriage, but No Divorce, in the Colonies Outside New E ngland ................................................................................... -

The Age of Reform After Fifty Years

Downloaded from https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781400001961 FORUM: RICHARD HOFSTADTER'S THE AGE OF REFORM AFTER FIFTY YEARS https://www.cambridge.org/core [Note: The following two essays are revised versions of presentations made by Robert Johnston and Gillis Harp at the annual meeting of the British American Nineteenth Century Historians (BrANCH) in Cambridge, England, in October 2005. BrANCH invited SHGAPE to help organize the conference. Based on a suggestion by Robert Johnston, SHGAPE con- tributed a session commemorating Richard Hofstadter's book on the Populist and Progressive movements, first published in 1955 and much-acclaimed and much-criticized since. While Professor Johnston had the assignment of assessing The Age of Reform in retro- . IP address: spect, Gillis Harp attempted to put the book within its contemporary intellectual context. Beyond evaluating this noteworthy book, the session had the intention as well of prompting memories from a few people in attendance who knew Hofstadter as a friend and colleague. 170.106.35.229 In this, the session succeeded, reminding those present that The Age of Reform reflected the personality of its author and is more than a historiographic interpretation against which one measures one's own views.! , on 25 Sep 2021 at 06:23:25 The Age of Reform: A Defense of Richard Hofstadter Fifty Years , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at On* Robert D. Johnston, University of Illinois at Chicago When we attend academic history conferences, it has become common to hold sessions honoring important books of the moment. This makes con- siderable sense, as authors get to engage with thoughtful critics in a process that, we hope, advances the discipline. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This Is Not A

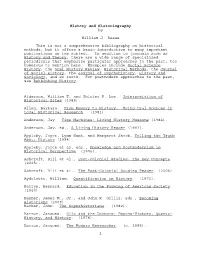

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This is not a comprehensive bibliography on historical methods, but it offers a basic introduction to many important publications on the subject. In addition to journals such as History and Theory, there are a wide range of specialized periodicals that emphasize particular approaches to the past, too numerous to mention here. Examples include Social Science History, the Oral History Review, Historical Methods, the Journal of Social History, the Journal of Psychohistory, History and Sociology, and so forth. For postmodern approaches to the past, see Rethinking History. Alderson, William T. and Shirley P. Low. Interpretation of Historical Sites (1985). Allen, Barbara. From Memory to History: Using Oral Sources in Local Historical Research. (1981). Anderson, Jay. Time Machines: Living History Museums (1984). Anderson, Jay, ed., A Living History Reader (1991). Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (1994). Appleby, Joyce et al, eds., Knowledge and Postmodernism in Historical Perspective. (1996). Ashcroft, Bill et al., Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts. (2005). Ashcroft, Bill et al., The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. (2006) Aydelotte, William. Quantification in History. (1971). Bailyn, Bernard. Education in the Forming of American Society. (1960) Banner, James M., Jr., and John R. Gillis, eds., Becoming Historians (2009). Barker, John. The Superhistorians. (1982). Barzun, Jacques. Clio and the Doctors: Psycho-History, Quanto- History, and History. (1976). Barzun, Jacques. The Modern Researcher. (c. 1985). 1 Barzun, Jacques. Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers. (1985). Beauchamp, Edward. Dissertations in the History of Education, 1970-1980. (1985). Becker, Carl. Everyman His Own Historian. -

The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter 45

The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter 45 The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter Ryan Coates Third Year Undergraduate, Durham University ‘We have all been taught to regard it as more or less “natural” for young dissenters to become conservatives as they grow older.’ Richard Hofstadter So proved to be the case for the author of this statement, the outstanding American historian of the twentieth century, Richard Hofstadter (1916-70). This assertion challenges the dominant orthodox portrayal of Hofstadter as the iconic public intellectual of post-war American liberalism. The orthodox interpretation, supported by biographer David Brown and historians Arthur Schlesinger and Sean Wilentz, demonstrates Hofstadter’s ideological progression from thirties radical, briefly a member of the Communist Party, to fifties liberal credited as the founder of consensus history.1 This interpretation draws upon Hofstadter’s most political works, includingThe American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948), The Age of Reform (1955) and most prominently, the essays collected in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1964), to reveal an apparent all-encompassing hostility toward conservatism. The revisionist interpretation, advanced by Hofstadter’s fellow New York intellectual Alfred Kazin and historians Robert Collins, Daniel Walker Howe and Peter Elliott Finn, challenges this one-dimensional portrayal of Hofstadter’s complex relationship to conservatism.2 Rather than flourishing into the iconic historian of American liberalism, the revisionists contend, Hofstadter’s intellectual development represented a gradual transition that had, by the end of his shortened life, culminated in a conversion to Burkean conservatism. Indeed, Kazin’s description of Hofstadter as a ‘secret conservative in a radical period’ encourages parallels 1 David S. -

HISTORY Copy.Pages

! ! ! QUOTES ON HISTORY ! ! Civilization is a stream with banks. The stream is sometimes filled with blood from people killing stealing, shouting and doing the things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry and even whittle statues. The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. Historians are pessimists because they ignore the banks for the river. ! --Will Durant The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like. ! —E. L. Doctorow History gives us the facts, sort of, but from literary works we can learn what the past smelled like, sounded like, and felt like, the forgotten gritty details of a lost era. Literature brings us as close as we can come to reinhabiting the past. By re- claiming this use of literature in the classroom, perhaps we can move away from the political agitation that has been our bread and butter—or porridge and hardtack— for the last 30 years. ! —Scott Herring Great novelists are the true historians of the times in which they live. Stop and think about it for a minute and I’m sure you’ll find that you didn’t get your impres- sions of what life was like here and abroad in the last 300 years from the history books—but from the novels of such literary titans as Hardy, Dostoevsky, Dickens, Sinclair Lewis, Jane Austen, and Tolstoy. Writers like these had a kind of extrasen- sory perception which enabled them to see beneath the surface of the age—and, of course, the genius to bring people and events to life in stories that enthralled read- ers of their own time as well as later generations.