Becoming Indians: Cervantes and García Lorca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Srl No Folio/Client ID Name of the Member to Whom the Amount of Dividend Is Due (To Be Given in Alphabetical Order) Last Known A

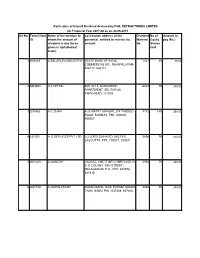

Particulars of Unpaid Dividend declared by IFGL REFRACTORIES LIMITED for Financial Year 2007-08 as on 20.09.2015 Srl No Folio/Client Name of the member to Last known address of the Dividend No of Amount to ID whom the amount of person(s) entitled to receive the Warrant Equity pay (Rs.) dividend is due (to be amount No. Shares given in alphabetical held order) 1 B03445 A BALAGURU MOORTHY STATE BANK OF INDIA, 1421 35 70.00 COMMERCIAL BR., RAJAPALAYAM- 626117, 626117 2 M03408 A C MITTAL 305, GH-8, SARASWATI 6429 70 140.00 APARTMENT, SECTOR-46, FARIDABAD, 121003 3 S01862 A C SHAH 8/23 MATRY MANDIR, 278 TARDEO 9172 140 280.00 ROAD, BOMBAY, PIN : 400007, 400007 4 L01301 A G SERVICES PVT LTD 1/2 LORD SINHA RD 2ND FLR, 5696 70 140.00 CALCUTTA, PIN : 700071, 700071 5 G01203 A GANESH VADIVEL CHETTIAR COMPOUND, N 2934 70 140.00 G O COLONY 6TH STREET, MELAGARAM P.O., PIN : 627818, 627818 6 G01749 A GOPALASAMY INDIAN BANK, RASI PURAM, SALEM 3057 70 140.00 TAMIL NADU, PIN : 637408, 637408 7 C01906 A HUKMI CHAND SUPREME COMPUTER SERVICES, 1933 105 210.00 44 M K TEMPLE ST OPP UBI SRI VITTAL, COMPLEX 1ST FLR B V K IYENGAR RD, BANGALORE PIN : 560053, 560053 8 J03026 A JOY HEMANTH, B M C POST, COCHIN, 4303 35 70.00 PIN : 682021, 682021 9 D03059 A K DHINAKARAN Y-94 2ND FLOOR 8TH STREET, 6TH 2658 70 140.00 MAIN ROAD, ANNA NAGAR CHENNAI, PIN : 600040, 600040 10 S08488 A KUMARA SWAMY HOUSE NO 12-6*48 S U N ROAD, 10344 70 140.00 WARANGAI, A P, PIN : 506002, 506002 11 12348869IN A MALLESHWAR RAO H NO 12-1-118, P V STREET, 14501 5 10.00 300394 WARANGAL, 506002 -

Las Transformaciones De Aldonza Lorenzo

Lemir 14 (2010): 205-215 ISSN: 1579-735X ISSN: Las transformaciones de Aldonza Lorenzo Mario M. González Universidade de São Paulo RESUMEN: Aldonza Lorenzo aparece en el Quijote tan solo como la base real en que se apoya la creación de la dama del caballero andante, Dulcinea del Toboso, a partir del pasado enamoramiento del hidalgo por la labradora. No obstante, permanece en la novela como una referencia tanto para don Quijote como para su escudero. Para el caballero, lo que permite esa aproximación es la hermosura y la honestidad de una y otra, exacta- mente los atributos que Sancho Panza niega radicalmente en Aldonza para crear lo que puede llamarse una «antidulcinea». A la obsesión de don Quijote por desencantar a Dulcinea, parecería subyacer la de salvar la hermosura y honestidad de Aldonza Lorenzo. De hecho, cuando todos los elementos de la realidad son paulatinamente recuperados por el caballero en su vuelta a la cordura, la única excepción es Aldonza Lo- renzo, de quien Alonso Quijano sugestivamente nada dice antes de morir. ABSTRACT: Aldonza Lorenzo appears in Cervantes’s Don Quixote merely as the source that gave birth to the knight- errant’s imagined ladylove Dulcinea del Toboso ever since the Hidalgo fell in love with the farm girl in the past. However, Aldonza Lorenzo remains a reference to Don Quixote and his squire Sancho Panza throughout the novel. For the knight, beauty and honesty aproximate both girls, the real and the imagi- nary, while his squire denies those virtues in Aldonza creating what can be defined as an «anti-dulcinea». -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Sobre Crítica Del «Quijote» La Razón Que Nutren La Cultura Y La Reflexión, La Voz De Alonso Quijano

SOBRE CRÍTICA DEL QUIJOTE Maxime Chevalier Hace varias décadas que deja pendientes la crítica cervantina unas preguntas esenciales. Me refiero a la relación entre Cervantes y el protagonista del Qui• jote, por una parte, y, por otra parte, al concepto en que tenía Cervantes los libros y la cultura libresca. Sobre ambas preguntas quisiera explicarme hoy. La primera pregunta la planteó la edad romántica al afirmar que Cervan• tes mal había entendido la grandeza de su héroe. Tal concepto iba ya en germen en la conocida frase de la Estética hegeliana que define el asunto del Quijote como «oposición cómica entre un mundo ordenado según la razón [...] y un alma aislada», frase decisiva por señalar la pauta de la crítica deci• monónica, según la cual la novela cervantina es el conflicto entre prosaísmo y poesía, realidad e ideal, don Quijote y la sociedad. Al tomar este camino, se orientaban forzosamente los estudiosos a quienes competía la definición del protagonista hacia un elogio de la locura, un elogio de la locura radicalmente distinto del de Erasmo, que es elogio jocoso de la simpleza (stultitia).1 E iban a desembocar fatalmente en el dilema enunciado por Marthe Robert: de dos cosas la una, o bien abona el lector el buen sentido cervantino, hipótesis en la que don Quijote no pasa de ser un loco grotesco; o bien vemos en don Quijote una especie de santo escarnecido, y hemos de confesar que Cervantes no en• tendió su propia creación.2 Dilema finamente cincelado —y dilema inacepta• ble. Cualquier lector de buena fe en seguida advierte que dicho dilema no da cuenta de la realidad. -

Oceánide 4# 2012 Don Quixote and Jesus Christ

Oceánide 4 2012 Fecha de recepción: 24 diciembre 2011 Fecha de aceptación: 20 enero 2012 Fecha de publicación: 25 enero 2012 URL:http://oceanide.netne.net/articulos/art4-15.php Oceánide número 4, ISSN 1989-6328 Don Quixote and Jesus Christ: The suffering “Idealists” of Modern Religion Rebekah Marzhan (Hamline University, Minnesota USA) RESUMEN: La figura de Don Quijote ha sido siempre examinada como la de un personaje que simboliza el absurdo de la búsqueda idealista. Por lo tanto, incontables generaciones han sido capaces de apropiarse temporalmente de este caballero medieval como representante de su propia situación histórica. A través de muy diversa tradición poética, ensayística, o novelesca, grandes pensadores han elevado el espíritu del Quijote desde las páginas de Cervantes, y revivido a este loco caballero como símbolo, no solo como estandarte de la fe en uno mismo, sino también de la fe en el sentido religioso o espiritual en este mundo moderno y racional. Si bien esta evolución del pensamiento ha sido desarrollada y explorada a través de diversos movimientos literarios, el análisis de ilustraciones modernas de Don Quijote han sido ampliamente descuidadas. En otras palabras, para apreciar la evolución del espíritu quijotesco ha de prestarse especial atención a las composiciones artísticas del siglo XX, con la obra de Salvador Dalí a la cabeza. Con una edición de 1945 de la obra cervantina, Dalí refleja a través de la iconografía cristiana la figura de un Don Quijote irracional que sufre a causa de su idealismo. Palabras clave: Don Quijote, Dalí, análisis visual, sufrimiento, Cristianismo. ABSTRACT: The figure of Don Quixote has always been seen as a character symbolizing the absurdity of idealistic pursuits. -

The Universal Quixote: Appropriations of a Literary Icon

THE UNIVERSAL QUIXOTE: APPROPRIATIONS OF A LITERARY ICON A Dissertation by MARK DAVID MCGRAW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Eduardo Urbina Committee Members, Paul Christensen Juan Carlos Galdo Janet McCann Stephen Miller Head of Department, Steven Oberhelman August 2013 Major Subject: Hispanic Studies Copyright 2013 Mark David McGraw ABSTRACT First functioning as image based text and then as a widely illustrated book, the impact of the literary figure Don Quixote outgrew his textual limits to gain near- universal recognition as a cultural icon. Compared to the relatively small number of readers who have actually read both extensive volumes of Cervantes´ novel, an overwhelming percentage of people worldwide can identify an image of Don Quixote, especially if he is paired with his squire, Sancho Panza, and know something about the basic premise of the story. The problem that drives this paper is to determine how this Spanish 17th century literary character was able to gain near-univeral iconic recognizability. The methods used to research this phenomenon were to examine the character´s literary beginnings and iconization through translation and adaptation, film, textual and popular iconography, as well commercial, nationalist, revolutionary and institutional appropriations and determine what factors made him so useful for appropriation. The research concludes that the literary figure of Don Quixote has proven to be exceptionally receptive to readers´ appropriative requirements due to his paradoxical nature. The Quixote’s “cuerdo loco” or “wise fool” inherits paradoxy from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s In Praise of Folly. -

Under the Influence of Cervantes: Trapiello's Al Morir Don Quijote

Under the Influence of Cervantes: Trapiello’s Al morir don Quijote Dr. Isidoro Arén Janeiro Independent Scholar Yor the last four hundred years, Cervantes’ masterpiece, Don Quixote (1605- 1615), has influenced literary creation, and it has conditioned the authors who dared to distinguish themselves from one of the monsters of literature. It has been argued that there is a before and an after the first publication of the Primera parte del Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605). In essence, giving it the status of being the first “original”: the first modern novel that set the tone for the process of narrative production in Spain. Afterwards, all writers owed Cervantes, and are obliged into a conscious effort to swerve from the “original,” so as to differentiate their work by taking their narrative one step away; thus, positioning their work next to the “original” as a unique creation on its own. The aim of this article is to study these aspects, and to present an overview of the influence upon Andrés Trapiello’s Al morir Don Quijote (2005) by its predecessor: Cervantes’ Don Quijote (1605-1615). It will also analyse the complexity of the Cervantes’ masterpiece and the relationship established between the Primera parte del Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha (1605), the “original,” and the Segunda Parte del Ingenioso Caballero Don Quijote de la Mancha (1615). Additionally, it will present a study of Trapiello’s Al morir don Quijote, where the betrayal of Alonso Quijano is the central aspect that defines this novel. Finally, it will take into account Harold Bloom’s work The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, and it will analyse the intricate relationship between Trapiello and his text, as it is overshadowed by its predecessor. -

Decoding Madness Through Psychological Theory

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2021 QUIJANO AS QUIJOTE: DECODING MADNESS THROUGH PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY Cristian Rivera Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Spanish Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rivera, Cristian, "QUIJANO AS QUIJOTE: DECODING MADNESS THROUGH PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY" (2021). LSU Master's Theses. 5275. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/5275 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUIJANO AS QUIJOTE: DECODING MADNESS THROUGH PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures by Cristian Rivera M.S., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 2017 May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee for their guidance in completing my thesis. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Carmela Mattza especially for dedicating her time and expertise to this project and for being a caring advisor. I would also like to thank my friends and family for the support and encouragement they have shown me throughout this program and my entire academic career. Lastly, I would like to thank the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures and the Hispanic Studies faculty and staff at LSU for providing me with the many opportunities that have contributed substantially to my success as an academic professional. -

Cervantes the Cervantes Society of America Volume Xxvi Spring, 2006

Bulletin ofCervantes the Cervantes Society of America volume xxvi Spring, 2006 “El traducir de una lengua en otra… es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés.” Don Quijote II, 62 Translation Number Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Wiemer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editors: Daniel Eisenberg Tom Lathrop Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Editorial Board John J. Allen † Carroll B. Johnson Antonio Bernat Francisco Márquez Villanueva Patrizia Campana Francisco Rico Jean Canavaggio George Shipley Jaime Fernández Eduardo Urbina Edward H. Friedman Alison P. Weber Aurelio González Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes, official organ of the Cervantes Society of America, publishes scholarly articles in Eng- lish and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Tw i ce yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $20.00 a year for individuals, $40.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Theresa Sears, 6410 Muirfield Dr., Greensboro, NC 27410. -

The Search for Dog in Cervantes

humanities Article Article The Search for Dog in Cervantes ID Ivan Schneider Seattle, WA 98104,98104, USA; [email protected] Received: 20 20 March March 2017 2017;; Accepted: 11 11 July July 2017 2017;; Published: 14 14 July July 2017 2017 Abstract: This paper reconsiders the missing galgo from the first line in Don Quixote with a set of Abstract: This paper reconsiders the missing galgo from the first line in Don Quixote with a set of interlocking claims: first, that Cervantes initially established the groundwork for including a talking interlocking claims: first, that Cervantes initially established the groundwork for including a talking dog in Don Quixote; second, through improvisation Cervantes created a better Don Quixote by dog in Don Quixote; second, through improvisation Cervantes created a better Don Quixote by transplanting the idea for a talking dog to the Coloquio; and third, that Cervantes made oblique transplanting the idea for a talking dog to the Coloquio; and third, that Cervantes made oblique references to the concept of dogs having human intelligence within the novel. references to the concept of dogs having human intelligence within the novel. Keywords: Cervantes; talking dogs; narratology; animal studies Keywords: Cervantes; talking dogs; narratology; animal studies 1. Introduction 1. Introduction “[Cervantes] saw his scenes and the actors in them as pictures in his mind before he put “[Cervantes]them on paper, saw much his scenes as El Greco and the [see actors Figure in1] madethem as little pictures clay models in his ofmind his figuresbefore beforehe put thempainting on paper, them.” much (Bell as1947 El ,Greco p. -

A1076 A2201 Jagjit Singh Sethi Prithvijit Singh Wz-30

A1076 A2201 JAGJIT SINGH SETHI PRITHVIJIT SINGH WZ-30, MEENAKSHI GARDEN, NEAR SUBHASH TOWER 17,FLAT NO.603,SOUTH CLOSER NAGAR MERTRO STATION, NEW DELHI SECTOR-50,GURGOAN Contact: ----- Contact: 9810411980 ----- ----- NEW DELHI - 110018, Delhi GURGAON - 0, Haryana A1190 A2263 M.P. AGARWAL BHUPINDER SINGH 517, BRAHMANIPURA, RAJA RAM AGARWAL HOUSE NO. 22, SECTOR-3, CHANDIGARH- MARG, BEHIND JAIN MANDIR, BAHRAICH - (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: ----- ----- ----- BAHRAICH - 271801, Uttar Pradesh CHANDIGARH - 0, Chandigarh A1564 A2693 SHAMJIT SINGH SODHI MOHD. AFZAL E-352, GREATER KAILASH-II, 2ND FLOOR, NEW M/S KHAIR-UD-DIN SONS & CO., 7- EXTN DELHI- 110048 INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, JAMMU- 180 003 Contact: 9810592921 Contact: 191,2431390,09419141625 ----- ----- GREATER KAILASH-II - 110048, Delhi JAMMU - 180003, Jammu And Kashmir A1603 A3288 DR. ABUL FAZAL SYED KHALID HUSSAIN C/O- DR. A. F. FAIZY DEPTT. OF BIOCHEMISTRY, C-3/7, VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI J. N. MEDICAL COLLEGE, AMU, ALIGARH, UP Contact: 09756956133 Contact: ----- ----- ----- ALIGARH - 202002, Uttar Pradesh VASANT VIHAR - 110057, Delhi A2171 A3372 NARENDRA KUMAR MEHTA SATYAPADOO BHATTACHARYA 638,DDA SFS POCKET-I SECTOR22,DWARKA-I D-26/17 NARAD GHAT, VARANASI (U.P) NEW DELHI Contact: 9313573057 Contact: ----- ----- ----- DELHI - 110075, Delhi VARANASI - 0, Uttar Pradesh A3483 A5106 ASHOK KUMAR SINHA RAJIV BHATIA ASHOK MANSION , ANNIE BESANT ROAD, A-4/537,PACHIM VIHAR,NEW DELHI OPP- PATNA COLLEGE, PATNA- 100004 (BIHAR) Contact: ----- Contact: 9871811444 ----- ----- PATNA - 800004, Bihar PASCHIM VIHAR - 110063, Delhi A3655 A5126 H. C. PATHIK MOHD. G. ANSARI RAJA DY. DIR. SPORTS (RETD.) VILL & POST- ROHRU, 4107, MANDI STREET, NEAR PUL DISTT- SHIMLA HILLS, HIMACHAL PRADESH KAMBOH, SAHARANPUR (UP) Contact: ----- Contact: 09358971388 ----- ----- SHIMLA - 171207, Himachal Pradesh SAHARANPUR - 247001, Uttar Pradesh A4147 A5181 S. -

Review of José Ángel Ascunce Arrieta's Book: El Quijote Como

Volume 28.1 (2008) Reviews 205 Beusterien claims that “Cervantes intentionally invokes the noun negra” (143) through the dance of the chacona performed by the nephew and in so doing “he criticizes White drama and its appropriation of Africanness in his burlesque of the character of the nephew dancing the chacona.” (164). Through the inclusion of the dance, the negra is “present, but not present” suggesting that Whiteness is “revealed and foreclosed in this European musical context” (165). Compelling points for Beusterein’s case, for this read- er, include the fact that the African-inspired dance is performed with an invisible Jew- ish woman, thus providing both denarrativized and narrativized forms of racism at the same time while “upend[ing] race and gender hierarchies” (165), such as Juana Macha and Juan Castrado. Despite the skepticism with which some readers will react to Beusterien’s argu- ment of the connection between the adjectivenegra” “ and the broader historical context of Afro-Hispanic difference, his discussion is illuminating. He posits that “the negra in the comedia is a stock type characterized as a base sexualized object. Her skin color is sexual fantasy” (146). Yet, evidently, she is represented onstage as “anti-female,” often played by a male. Her dangerous darkness contrasts with the exotic whiteness of the Jewish female, and each represents colonial desire and religious desire, respectively. (For this reader, a sign of a perhaps over-eager application of this is Beusterien’s assumption that the character Jacinta (“una esclava herrada”) in El médico is a Black slave and not Moorish.) That said, Beusterien’s An Eye on Race provokes readers to take another look at these texts, some well known and others more obscure.