From Fleets to Navies: the Evolution of Dominion Fleets Into the Independent Navies of the Commonwealth James Goldrick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Call the Hands

CALL THE HANDS Issue No. 7 April 2017 From the President Welcome to Call the Hands. Our focus this month is on small vessels that played a large role in Australia's naval history. Similarly, some individuals and small groups who are often overlooked are covered. We look at a young Australian, the little known WW1 naval pilot, Lieutenant R. A. Little who became an ace flying with the Royal Navy Air Service and 11 sailors from HMAS Australia who participated with distinction in the 1918 raid on Zeebrugge. As many stories cannot be covered in detail I hope you find the links and recommended ‘further reading’ of value. Likewise, the list of items included in ‘this month in history’ is larger. This may wet appetites to search our website for relevant stories of interest. I would like to acknowledge the recent gift of a collection of books and DVDs to the Society's library by Mrs Jocelyn Looslie. Sadly, her husband, RADM Robert Geoffrey Looslie, CBE, RAN passed away on 5 September 2016 at age 90. His long and distinguished career of 41 years commencing in 1940 included four sea commands. One of these was the guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane (1971–1972). During this period Brisbane conducted its second Vietnam deployment. David Michael From the Editor Occasional Paper 6 published in March 2017 listed RAN ships lost over a century. Whilst feedback was positive we acknowledge subscribers and members who pointed out omissions which included; HMA ships Tarakan1, Woomera and Arrow. The tragic circumstances of their loss and the lives of their sailors underscores the inherent risks our men and women face daily at sea in peace and war. -

Australian Navy Commodore Allan Du Toit Relieved Rear Adm

FESR Archive (www.fesrassociation.com) Documents appear as originally posted (i.e. unedited) ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Visitors Log: Archived Messages: General: October to December 2007 The FESR Visitors Log http://fesrassociation.com/cgi-bin/yabb2/YaBB.pl General >> Bulletin Board >> RAN Commodore Takes Over CTF 158 http://fesrassociation.com/cgi-bin/yabb2/YaBB.pl?num=1191197194 st Message started by seashells on Oct 1 , 2007, 10:06am Title: RAN Commodore Takes Over CTF 158 Post by seashells on Oct 1st, 2007, 10:06am NSA, Bahrain -- Royal Australian Navy Commodore Allan du Toit relieved Rear Adm. Garry E. Hall as commander of Combined Task Force (CTF) 158 during a ceremony at Naval Support Activity Bahrain Sept. 27. Command of CTF 158 typically rotates among coalition partners Australia, United Kingdom and the United States. CTF 158 is comprised of coalition ships and its primary mission in the Persian Gulf is Maritime Security Operations (MSO) in and around both the Al Basrah and Khawr Al Amaya Oil Terminals (ABOT and KAAOT, respectively), in support of U.N. Security Council Resolution 1723. This resolution charges the multinational force with the responsibility and authority to maintain security and stability in Iraqi territorial waters and also supports the Iraqi government's request for security support. Additionally, under the training and leadership of CTF 158, Iraqi marines aboard ABOT and KAAOT train with the coalition in order to eventually assume responsibility for security. “I am honored to have been in command of this task force,” said Hall. “The coalition forces have done an excellent job of providing security to the oil platforms and training the Iraqi forces.” “I am very proud of the coalition forces and my staff in supporting the CTF 158 mission,” said Capt. -

An Analysis of the Loss of HMAS SYDNEY

An analysis of the loss of HMAS SYDNEY By David Kennedy The 6,830-ton modified Leander class cruiser HMAS SYDNEY THE MAIN STORY The sinking of cruiser HMAS SYDNEY by disguised German raider KORMORAN, and the delayed search for all 645 crew who perished 70 years ago, can be attributed directly to the personal control by British wartime leader Winston Churchill of top-secret Enigma intelligence decodes and his individual power. As First Lord of the Admiralty, then Prime Minster, Churchill had been denying top secret intelligence information to commanders at sea, and excluding Australian prime ministers from knowledge of Ultra decodes of German Enigma signals long before SYDNEY II was sunk by KORMORAN, disguised as the Dutch STRAAT MALAKKA, off north-Western Australia on November 19, 1941. Ongoing research also reveals that a wide, hands-on, operation led secretly from London in late 1941, accounted for the ignorance, confusion, slow reactions in Australia and a delayed search for survivors . in stark contrast to Churchill's direct part in the destruction by SYDNEY I of the German cruiser EMDEN 25 years before. Churchill was at the helm of one of his special operations, to sweep from the oceans disguised German raiders, their supply ships, and also blockade runners bound for Germany from Japan, when SYDNEY II was lost only 19 days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Southeast Asia. Covering up of a blunder, or a punitive example to the new and distrusted Labor government of John Curtin gone terribly wrong because of a covert German weapon, can explain stern and brief official statements at the time and whitewashes now, with Germany and Japan solidly within Western alliances. -

Australian Update: August 2018

Australian Update: August 2018 Dr. Robbin Laird, Research Fellow, Williams Foundation, Canberra THE AUSTRALIAN NEW SUBMARINE PROGRAM: CLEARLY A WORK IN PROGRESS 3 AUSTRALIA BROADENS ITS MILITARY RELATIONSHIPS WITH SHIPBUILDING DEALS 7 THE COMMANDER OF THE RAAF AIR WARFARE CENTRE, AIR COMMODORE “JOE” IERVASI 10 THE AUSTRALIANS SHAPE THEIR WAY AHEAD ON ASW: THE KEY ROLE OF THE P-8 13 FLEET BASE EAST: A KEY ELEMENT IN THE AUSTRALIAN NAVY’S OPERATIONAL CAPABILITIES 16 THE AEGIS GLOBAL ENTERPRISE: THE AUSTRALIAN CASE 21 APPENDIX: THE AIR WARFARE DESTROYER ALLIANCE 23 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE HOBART CLASS DESTROYERS 24 THE HOBART CLASS – DIFFERENCES FROM THE F100 CLASS 25 DR. BEN GREENE, ELECTRICAL OPTICAL SYSTEMS 26 APPENDIX 30 PITCH BLACK 2018: RAAF PERSPECTIVES 31 THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY AND INTEGRATED AIR DEFENSE 34 APPENDIX: 35 LOOKING BACK AT RIMPAC 2018: THE PERSPECTIVE OF AIR COMMODORE CRAIG HEAP 36 SHAPING ENHANCED SOVEREIGN OPTIONS: LEVERAGING THE INTEGRATED FORCE BUILDING PROCESS 40 THE DEFENSE OF AUSTRALIA: LOOKING BACK AND LEANING FORWARD 43 2 The Australian New Submarine Program: Clearly A Work in Progress 8/19/18 Canberra, Australia During my current visit to Australia, I have been able to follow up the discussions with the Chief of Navy over the past three years with regard to shipbuilding and shaping a way ahead for the Royal Australian Navy. During this visit I had a chance to visit the Osborne shipyards and get an update on Collins class and enhanced availability as well as to get a briefing and discussion with senior Australian officials involved in shaping the new build submarine program. -

On 21 June 2008, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) Will Celebrate the Third Annual United Nations World Hydrography Day

1 of 7 WORLD HYDROGRAPHY DAY 2008 ADDRESS BY COMMANDER BORDER PROTECTION COMMAND 20 June 2008 Your Excellency, Mr Charles Lepani, Papua New Guinea High Commissioner to Australia; The Honourable Mr Greg Combet, MP, Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Procurement; Ms Sharon Bird, MP, Member for Cunningham; Mr Jim Turnour, MP, Member for Leichhardt The Hydrographer of Australia, CDRE Rod Nairn; Mr Joseph Kunda, Hydrographer of Papua New Guinea; Ladies and Gentlemen; As part of Navy’s Hydrographic Meteorological and Oceanographic Force Element Group, the Australian Hydrographic Service fulfils a number of important military and commercial roles. Today, hydrographic survey continues to play a key role as a public good in activities that maintain and enhance Australia’s national authority, influence and well-being. Tomorrow, on 21 June 2008, the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) will celebrate the third annual United Nations World Hydrography Day. The theme for the 2008 celebrations is …. Capacity Building, a vital tool to assist the IHO in achieving its mission and objectives. In keeping with this theme, today we take the opportunity to recognise Australia’s hydrographic contribution to capacity building 2 of 7 in our region, and to celebrate the achievements of Australia’s own Hydrographic Service. Capacity building is a key priority for the IHO. This year’s World Hydrography Day celebrations highlight the IHO’s commitment to supporting technology and skills transfer between established and newly-developing Hydrographic Offices in the interests of enhancing global navigational safety, maritime trade and protection of the marine environment. To support this priority, the IHO has defined a three-phase development strategy to build national hydrographic capacity worldwide. -

Command: a Historical Perspective

2020, VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 AN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES COMMAND: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Rear Admiral (Ret) James Goldrick Royal Austrailian Navy CENTER FOR CHARACTER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT EDITORIAL STAFF: EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. Mark Anarumo, Dr. David Altman, Center for Creative Managing Editor, Colonel, USAF Leadership Dr. Douglas Lindsay, Dr. Marvin Berkowitz, University of Missouri- Editor in Chief, USAF (Ret) St. Louis Dr. John Abbatiello, Dr. Dana Born, Harvard University Book Review Editor, USAF (Ret) (Brig Gen, USAF, Retired) Dr. David Day, Claremont McKenna College Ms. Julie Imada, Editor & CCLD Strategic Dr. Shannon French, Case Western Communications Chief Dr. William Gardner, Texas Tech University JCLD is published at the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Mr. Chad Hennings, Hennings Management Colorado. Articles in JCLD may be Corp reproduced in whole or in part without permission. A standard source credit line Mr. Max James, American Kiosk is required for each reprint or citation. Management For information about the Journal of Dr. Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University Character and Leadership Development or the U.S. Air Force Academy’s Center Dr. Robert Kelley, Carnegie Mellon for Character and Leadership University Development or to be added to the Association of Graduates Journal’s electronic subscription list, Ms. Cathy McClain, (Colonel, USAF, Retired) contact us at: Dr. Michael Mumford, University of [email protected] Oklahoma Phone: 719-333-4904 Dr. Gary Packard, United States Air Force Academy (Colonel, USAF) The Journal of Character & Leadership Development Dr. George Reed, University of Colorado at The Center for Character & Leadership Colorado Springs (Colonel, USA, Retired) Development Rice University U.S. -

The Need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick

Corbett Paper No 7 The need for a New Naval History of The First World War James Goldrick The Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies November 2011 The need for a New Naval History of the First World War James Goldrick Key Points . The history of naval operations in the First World War urgently requires re- examination. With the fast approaching centenary, it will be important that the story of the war at sea be recognised as profoundly significant for the course and outcome of the conflict. There is a risk that popular fascination for the bloody campaign on the Western Front will conceal the reality that the Great War was also a maritime and global conflict. We understand less of 1914-1918 at sea than we do of the war on land. Ironically, we also understand less about the period than we do for the naval wars of 1793-1815. Research over the last few decades has completely revised our understanding of many aspects of naval operations. That work needs to be synthesized and applied to the conduct of the naval war as a whole. There are important parallels with the present day for modern maritime strategy and operations in the challenges that navies faced in exercising sea power effectively within a globalised world. Gaining a much better understanding of the issues of 1914-1918 may help cast light on some of the complex problems that navies must now master. James Goldrick is a Rear Admiral in the Royal Australian Navy and currently serving as Commander of the Australian Defence College. -

FROM CRADLE to GRAVE? the Place of the Aircraft

FROM CRADLE TO GRAVE? The Place of the Aircraft Carrier in Australia's post-war Defence Force Subthesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES at the University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1996 by ALLAN DU TOIT ACADEMY LIBRARy UNSW AT ADFA 437104 HMAS Melbourne, 1973. Trackers are parked to port and Skyhawks to starboard Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Allan du Toit Canberra, October 1996 Ill Abstract This subthesis sets out to study the place of the aircraft carrier in Australia's post-war defence force. Few changes in naval warfare have been as all embracing as the role played by the aircraft carrier, which is, without doubt, the most impressive, and at the same time the most controversial, manifestation of sea power. From 1948 until 1983 the aircraft carrier formed a significant component of the Australian Defence Force and the place of an aircraft carrier in defence strategy and the force structure seemed relatively secure. Although cost, especially in comparison to, and in competition with, other major defence projects, was probably the major issue in the demise of the aircraft carrier and an organic fixed-wing naval air capability in the Australian Defence Force, cost alone can obscure the ftindamental reordering of Australia's defence posture and strategic thinking, which significantly contributed to the decision not to replace HMAS Melbourne. -

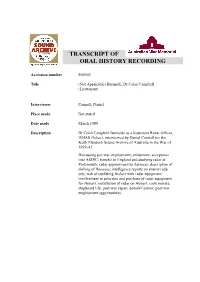

Transcript of Oral History Recording

TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL HISTORY RECORDING Accession number S00543 Title (Not Applicable) Burnside, Dr Colin Campbell (Lieutenant) Interviewer Connell, Daniel Place made Not stated Date made March 1989 Description Dr Colin Campbell Burnside as a lieutenant Radar Officer, HMAS Hobart, interviewed by Daniel Connell for the Keith Murdoch Sound Archive of Australia in the War of 1939–45 Discussing pre-war employment; enlistment; acceptance into ASDIC; transfer to England and studying radar at Portsmouth; radar appointment to Adelaide; description of sinking of Rameses; intelligence reports on enemy radar sets; task of outfitting Hobart with radar equipment; involvement in selection and purchase of radar equipment for Hobart; installation of radar on Hobart; crew morale; shipboard life; post-war Japan; demobilisation; post-war employment opportunities. COLIN CAMPBELL Page 2 of 34 Disclaimer The Australian War Memorial is not responsible either for the accuracy of matters discussed or opinions expressed by speakers, which are for the reader to judge. Transcript methodology Please note that the printed word can never fully convey all the meaning of speech, and may lead to misinterpretation. Readers concerned with the expressive elements of speech should refer to the audio record. It is strongly recommended that readers listen to the sound recording whilst reading the transcript, at least in part, or for critical sections. Readers of this transcript of interview should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal conversational style that is inherent in oral records. Unless indicated, the names of places and people are as spoken, regardless of whether this is formally correct or not – e.g. -

Anzac Parade and Our Changing Narrative of Memory1

Anzac Parade and our changing narrative of memory1 IAN A. DEHLSEN Abstract Australian historian Ken Inglis once called Canberra’s Anzac Parade ‘Australia’s Sacred Way’. A quasi-religious encapsulation of the military legends said to define our national character. Yet, it remains to be discussed how the memorials on Anzac Parade have been shaped by these powerful and pervasive narratives. Each memorial tells a complex story, not just about the conflicts themselves but also the moral qualities the design is meant to invoke. The Anzac Parade memorials chart the changing perceptions of Australia’s military experience through the permanence of bronze and stone. This article investigates how the evolving face of Anzac Parade reflects Australia’s shifting relationship with its military past, with a particular emphasis on how shifting social, political and aesthetic trends have influenced the memorials’ design and symbolism. It is evident that the guiding narratives of Anzac Parade have slowly changed over time. The once all-pervasive Anzac legends of Gallipoli have been complemented by multicultural, gender and other thematic narratives more attuned to contemporary values and perceptions of military service. [This memorial] fixes a fleeting incident in time into the permanence of bronze and stone. But this moment in our history—fifty years ago—is typical of many others recorded not in monuments, but in the memories of our fighting men told and retold … until they have passed into the folklore of our people and into the tradition of our countries.2 These were the words of New Zealand Deputy Prime Minister J.R. Marshall at the unveiling of the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial on Anzac Parade, Canberra, in the winter of 1968. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships. -

Person Name - Prefix a Table of Salutations That May Precede an Individual’S Name to Identify Social Status

Person Name - Prefix A table of salutations that may precede an individual’s name to identify social status. Accurate and uniform information is key to exchanging data. The table below is the recommended format for an individuals name prefix. Note: Military abbreviations are provided in Non Department of National Defence writing format as per "The Canadian Style, A Guide to Writing and Editing" published in 1997. Prefix Abbreviation Second Lieutenant 2nd Lieut. Acting Sub-Lieutenant Acting Sub-Lieutenant Able Seaman A.B. Abbot Ab. Archbishop Abp. Admiral Admiral Brigadier-General Brig.-Gen Brother Bro. Base Chief Petty Officer BsCPO Captain Capt. Commander Cmdr. Chief Chief Commodore Commodore Colonel Col. Constable Const. Corporal Cpl. Chief Petty Officer 1st class Chief Petty Officer, 1st class Chief Petty Officer 2nd class Chief Petty Officer, 2nd class Constable Cst. Chief Warrant Officer Chief Warrant Officer Doctor Dr. Bishop (Episcopus) Episc Your Excellency Exc. Father Fr. General Gen. Her Worship Her Worship Her Excellency HerEx His Worship His Worship His Excellency HisEx Honourable Hon. Lieutenant-Commander Lt.-Cmdr Lieutenant-Colonel Lt.-Col Lieutenant-General Lt.-Gen Leading Seaman L.S. Lieutenant Lieut. Monsieur M. Person Name - Prefix Prefix Abbreviation Master Ma. Madam Madam Major Maj. Mayor Mayor Master Corporal Master Corporal Major-General Maj.-Gen Miss Miss Mademoiselle Mlle. Madame Mme. Mister Mr. Mistress Mrs. Ms Ms. Master Seaman M.S. Monsignor Msgr. Monsieur Mssr. Master Mstr Master Warrant Officer Master Warrant Officer Naval Cadet Naval Cadet Officer Cadet Officer Cadet Ordinary Seaman O.S. Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 1st class Petty Officer, 2nd class Petty Officer, 2nd class Professor Prof.