“Thuringia in the Weimar Republic”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erfurt - Weimar - Jena West - Jena-Göschwitz - Gera HOLZLANDBAHN ൹ 565

Kursbuch der Deutschen Bahn 2020 www.bahn.de/kursbuch 565 Erfurt - Weimar - Jena West - Jena-Göschwitz - Gera HOLZLANDBAHN ൹ 565 VMT-Tarif Erfurt Hbf - Gera (IC, RE, EB); Anerkennung von Nahverkehrsfahrscheinen in den IC zwischen Erfurt und Gera RE 1 Göttingen - Erfurt - Gera - Glauchau ᵕᵖ; RE 3 Erfurt - Gera - Altenburg ᵕᵖ EB 21 Erfurt - Weimar - Jena-Göschwitz - Gera ᵕᵖ Zug EB 21 EB 21 EB 21 EB 21 RE 3 RE 3 RB 20 EB 21 ICE EB 21 RE 1 RE 1 EB 21 RE 3 RE 3 RE 3 80915 80796 80919 80875 3949 3901 74605 80877 698 80917 3653 3653 80879 3953 3903 3923 f hy Sa,So Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Sa Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Ẅ ẅ Ẇ ẇ Ẇ Ẇ Ẇ Ẇ km von Eisenach München Greiz Heilbad Hbf Heiligensta 51 6 ܥ 51 6 20 6 ܥ ẘẖ 5 44 ẘẖ 6 06 22 5 58 4 ܥ ẗẒ 4 37 ẗẔ 4 37 08 3 ܥ Erfurt Hbf ẞẖ ݝ 0 38 0 7 Vieselbach Ꭺ 0 43 ܥ 3 15 ܥᎪܥᎪܥ 5 03 Ꭺ ܥᎪ ܥᎪܥᎪ ᎪܥᎪ 14 Hopfgarten (Weimar) Ꭺ 0 48 ܥ 3 19 ܥᎪܥᎪܥ 5 08 Ꭺ ܥᎪ ܥᎪܥᎪ ᎪܥᎪ 21 Weimar ẞẖ ܙ 0 54 ܥ 3 25 ܥ 4 49 ܥ 4 49 ܥ 5 13 5 35 ܥ 5 55 ẘẖ 6 21 ܥ 6 32 7 04 ܥ 7 04 Weimar 0 55 ܥ 2 05 ܥ 3 25 ܥ 4 22 ܥ 4 51 ܥ 4 51 ܥ 5 17 ܥ 5 41 ܥ 5 57 ẗẔ 6 22 ܥ 6 34 7 06 ܥ 7 06 25 Oberweimar 0 59 ܥᎪܥᎪܥ4 26 ܥᎪܥᎪ ܥ5 21 ܥ 5 45 ܥᎪ ܥ6 26 ܥᎪ ᎪܥᎪ 29 Mellingen (Thür) 1 02 ܥᎪܥ3 31 ܥ 4 29 ܥᎪܥᎪ ܥ5 24 ܥ 5 48 ܥᎪ ܥ6 29 ܥᎪ ᎪܥᎪ 36 Großschwabhausen 1 07 ܥᎪܥ3 36 ܥ 4 34 ܥᎪܥᎪ ܥ5 29 ܥ 5 53 ܥᎪ ܥ6 34 ܥᎪ ᎪܥᎪ 44 Jena West ܙ 1 13 ܥᎪܥ3 42 ܥ 4 40 ܥ 5 04 ܥ 5 04 ܥ 5 35 ܥ 5 59 ܥ 6 10 ܥ 6 40 ܥ 6 48 7 20 ܥ 7 20 Jena West 1 14 ܥᎪܥ3 43 ܥ 4 41 ܥ 5 05 ܥ 5 05 ܥ 5 37 ܥ 6 00 ܥ 6 12 ܥ 6 41 ܥ 6 50 7 22 ܥ 7 22 26 7 ܥ 26 7 54 6 ܥ 46 6 ܥ 16 6 ܥ 05 6 ܥ 41 5 ܥ 09 5 ܥ 09 5 ܥ 46 4 ܥ 48 3 ܥ 51 2 ܥ 19 1 ܙ Jena-Göschwitz -

Villen, Bürger- Und Geschäftshäuser Im Landkreis Greiz

Landkreis Greiz Villen, Bürger- und Geschäftshäuser im Landkreis Greiz Villen, Bürger- und Geschäftshäuser im Landkreis Greiz Impressum Herausgeber: Landratsamt Greiz Konzept: Landratsamt Greiz, Untere Denkmalschutzbehörde Texte: Christian Espig Fotos: Christoph Beer Idee & Gestaltung: stark comm. GmbH – Agentur für Kommunikation und Werbung Druck: Druckerei Tischendorf, Greiz Stand: November 2011 Grußwort 3 Liebe Bürgerinnen und Bürger, liebe Besucher, der Landkreis Greiz weist eine einzigartige, beein- wie sich der Lebensstil des Bürgertums und der An- druckende und vielgestaltige Villenlandschaft auf. spruch auf Repräsentation, Luxus aber auch Kunst- sinnigkeit der damaligen Bauherrschaft wider- Die vorliegende Publikation gibt Einblicke in die an- spiegelt. spruchsvolle Baukultur der Villen, Bürger- und Ge- schäftshäuser des 19. Jahrhunderts und frühen 20. Die fotografischen Aufnahmen in der Publikation Jahrhunderts, die heute noch zu bewundern ist und belegen noch heute, auch bei leerstehenden Gebäu- den Landkreis prägt. den, den ästhetischen Anspruch und den Wohlstand der einstigen Bauherren des Industriezeitalters. Die Herausgeber beabsichtigen, die repräsentative Villenarchitektur mit den aufwändigen dekorativen Reisen Sie mit uns durch den landschaftlich und Fassaden und den schmuckvollen Details vorzustel- architektonisch reizvollen Landkreis und begleiten len und Hintergründe zu deren Baugeschichte zu Sie uns zu den ausgewählten Standorten bau licher vermitteln. Wohnkultur. Lernen Sie Bauzeugnisse vergange- ner Stilepochen -

Etix VVK Stellen

Altenburg Ticketgalerie GmbH Kornmarkt 1 D-04600 Bad Brückenau Mediengruppe Oberfranken Ludwigstraße 12 D-97769 Bad Kissingen Mediengruppe Oberfranken Theresienstr. 21 D-97688 Bad König Reisebüro Reisefenster Bahnhofstraß 12 D-64732 Bad Langensalza KTL Kur und Tourismus Bad Langensalza GmbH Bei der Marktkirche D-99947 Bad Liebenwerda Reisebüro Jaich Rossmarkt 5 D-04924 Bad Liebenwerda Wochenkurier Markt 16 D-04924 Bad Mergentheim Fränkische Nachrichten Verlags GmbH Kapuzinerstraße 4 (am Schloss) D-97980 Bad Salzungen Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT Andreasstr. 11 D-36433 Bamberg bvd Kartenservice Lange Str. 39/41 D-96047 Bamberg Kartenkiosk Bamberg Forchheimer Str. 15 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Hauptwachstr. 22 D-96047 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstr. 1 D-96050 Bamberg Mediengruppe Oberfranken Gutenbergstraße 1 D-96050 Bautzen Intersport Goschwitzstraße 2 D-02625 Bautzen SZ Bautzen Lauengraben 18 D-02625 Bautzen Wochenkurier Hauptmarkt 7 D-02625 Bayreuth Abokarten Verwaltungs GmbH BT - Nordbayerischer Kurier Theodor-Schmidt-Str. 17 D-95448 Bayreuth Theaterkasse Bayreuth Opernstraße 22 D-95444 Berlin Berliner KartenKontor im Forum Steglitz Schloßstr.1 D-12163 Berlin HOLIDAY LAND Reisebüro & Theaterkasse Schnellerstrasse 21 D-12439 Berlin Reisestudio Menzer Treskowallee 86 D-10318 Bitterfeld Reisebüro Bier Brehnaer Straße 34 D-06749 Borna Ticketgalerie GmbH Brauhausstraße 3 D-04552 Bremen Bremer KartenKontor bei Saturn in der Galeria Kaufhof Papenstr. 5 D-28195 Bremen Bremer Kartenkontor Zum Alten Speicher 9 D-28759 -

Thuringia Focus

August 2021 Thuringia Focus. Intercord dedicates new R&D center Mühlhausen has long been a produc- tion hub for technical yarns, espe- cially for the automotive industry. Its footprint is now set to grow: A new development center was officially com- missioned on Intercord’s Mühlhausen premises in mid-June. The company en- larged the research department, too. Intercord will conduct tests at the new development center, while customers and suppliers will have an opportuni- ty to perform material testing of their At the laying of the foundation stone for the new building of Carlisle in Waltershausen. Photo: Carlisle own. Intercord’s Managing Director Ra- mazan Yasbay believes the center will provide a comprehensive overview of On the growth track: US investor Carlisle the products and materials that custo- mers want. The CEO described the sale expands operations in Thuringia of the company last October to US- based Beaver Manufacturing Company (BMC) as a “lucky thing” and called the Plastics specialist Carlisle is growing 25 new jobs and increase the Thuringian family-owned company a good choice. and investing around EUR 50 million in site’s total internal area to 17,000 square Electric mobility, too, is an important a new production facility in Waltershau- meters. The company will also buy new issue for Intercord. New engines will sen, Thuringia. The expansion is proof equipment for producing its special wa- mean new requirements for technical positive that Thuringia’s excellent site terproofing membranes. These products fibers. The company and its 90 em- conditions and all-round service make a are a runaway success since they can be ployees appear well prepared. -

Mitteilungsblatt

AMTLICHES MITTEILUNGSBLATT Amtsblatt der Verwaltungsgemeinschaft Bad Tennstedt bestehend aus den Mitgliedsgemeinden: Bad Tennstedt, Ballhausen, Blankenburg, Bruchstedt, Haussömmern, Hornsömmern, Kirchheilingen, Klettstedt, Kutzleben, Mittelsömmern, Sundhausen, Tottleben und Urleben mit öffentlichen Bekanntmachungen der Mitgliedsgemeinden Jahrgang 28 | Nr. 8/2018 Freitag, den 27. April 2018 nächster Redaktionsschluss: Montag, den 30.04.2018 nächster Erscheinungstermin: Freitag, den 11.05.2018 Aus dem Inhalt Amtliche Bekanntmachungen - VG Bad Tennstedt - Bad Tennstedt - Sundhausen Veranstaltungen in der Ver- waltungsgemeinschaft - Maifeuer in Haussömmern - Maifeuer in Tottleben - 7. Crosslauf für Kinder in Sundhausen - „Anwassern“ im Kurpark Bad Tennstedt - Vogelstimmenwanderung in Mittelsömmern - Frühlingskonzert des Stad- torchesters Bad Tennstedt - Bücherzwerge in der Bib- liothek - Kurkonzerte in Bad Tennstedt - Release Party im Kosmo- laut Gemeindenachrichten - Frühjahrsputz in Bad Tennstedt - Danksagung an Jagdgenos- senschaft Haussömmern - Kita Kirchheilingen- Ein spannendes letztes Kinder- gartenjahr - Geburtstage im Mai Schulnachrichten - 1. Elternversammlung für die zukünftigen 1. Klassen der Sebastian- Kneipp-Grundschule Bad Tennstedt - Der Geografie-Wettbewer- bes Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Gymnasiums - Die Pressekonferenz der Novalis-Regelschule - Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn- Gymnasium hat hinter die Kulissen des KiKA geschaut - Ferienrückblick der THEPRA Grundschule Kirchheilingen Redaktionsschluss - Vorlesewettbewerb am für das nächste -

Recyclinghof Münchenbernsdorf CD /DVD

INFO J 5 Leerungstage Vorgestellt: Recyclinghof Münchenbernsdorf Abfrage im Internet unter Seit Kurzem finden Leichtverpackun- www.awv-ot.de, Menüpunkt die Münchenberns- gen (wie Jogurt- Leerungstage oder telefonisch dorfer und andere Becher, Tetra- im AWV Ostthüringen Bürger der Verwal- Packs, Spülmittel- Sperrmüll tungsgemeinschaft flaschen), Schrott, den Recyclinghof Elektro-Klein- Abfuhr -Anmeldung telefonisch in der Thomas- und Elektro- unter 01802 298 168 oder Müntzer-Straße 29. Großgeräten (wie 0365/8332150 Der neue Standort elektrische Zahn- Abgabe am Recyclinghof zu den im Gewerbegebiet bürste, Haar- Öffnungszeiten „Kirchtal“ ist gut trockner, Wasch- zu erreichen und maschine, Fern- Recyclinghöfe großflächig ange- seher), Altholz legt. Den idylli- (wie Türen, Die- Bad Köstritz schen Ausblick auf len, Paneele), H.-Schütz-Str. 20 die umliegenden Bauschutt, Bau- Tel. 0365/4375923 Felder kann der stellenabfällen Berga Mitarbeiter der (wie Fenster, Fotos:AWV August-Bebel-Str. 5 Entsorgungsgesell- Waschbecken, Tel. 0151/15461999 schaft mbH „Umwelt“, Herr Hammer, an seinen Regenrinnen), Grünschnitt, Korken, Haushalts- Greiz Arbeitstagen in Münchenbernsdorf zu den Öff- Batterien, Reifen und Altkleidern. Schadstoffe kön- An der Goldenen Aue 2 nungszeiten Mittwoch 10.00 - 16.00 Uhr und Frei- nen zur Stellzeit des Schadstoffmobils, an jedem 2. Tel. 03661/674133 tag 12.00 - 18.00 Uhr jedoch kaum genießen - er hat Freitag des Monats von 16.00 - 18.00 Uhr, ebenfalls St. Adelheid 10 im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes alle Hände voll zu abgegeben werden. tun. Der Kunde muss sich nicht allein mit seinem (über Schönfelder Str.) Wir weisen darauf hin, dass nicht alle der ange- Tel. 03661/3962 Sperrmüll, Schrott oder anderem abmühen - Herr Hammer (im kleinen Bild rechts) packt kräftig beim führten Abgabemöglichkeiten kostenfrei sind, Untergrochlitzer Str. -

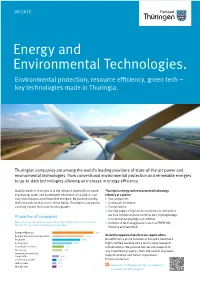

Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental Protection, Resource Efficiency, Green Tech – Key Technologies Made in Thuringia

09/2015 Energy and Environmental Technologies. Environmental protection, resource efficiency, green tech – key technologies made in Thuringia. Thuringian companies are among the world‘s leading providers of state-of-the-art power and environmental technologies: from conventional environmental protection and renewable energies to up-to-date technologies allowing an increase in energy efficiency. Quality made in Thuringia is in big demand, especially in waste Thuringia‘s energy and environmental technology processing, water and wastewater treatment, air pollution con- industry at a glance: trol, revitalization and renewable energies. By working closely > 366 companies with research institutions in these fields, Thuringia‘s companies > 5 research institutes can fully exploit their potential for growth. > 7 universities > leading engineering service providers in disciplines Proportion of companies such as industrial plant construction, hydrogeology, environmental geology and utilities (Source: In-house calculations according to LEG Industry/Technology Information Service, > market and technology leaders such as ENERCON, July 2013, N = 366 companies, multiple choices possible) Siemens and Vattenfall Seize the opportunities that our region offers. Benefit from a prime location in Europe’s heartland, highly skilled workers and a world-class research infrastructure. We provide full-service support for any investment project – from site search to project implementation and future expansions. Please contact us. www.invest-in-thuringia.de/en/top-industries/ environmental-technologies/ Skilled specialists – the keystone of success. Thuringia invests in the training and professional development of skilled workers so that your company can develop green, energy-efficient solutions for tomorrow. This maintains the competitiveness of Thuringian companies in these times of global climate change. -

How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia

— Early draft. Please do not quote, cite, or redistribute without written permission of the authors. — How Britain Unified Germany: Geography and the Rise of Prussia After 1815∗ Thilo R. Huningy and Nikolaus Wolfz Abstract We analyze the formation oft he German Zollverein as an example how geography can shape institutional change. We show how the redrawing of the European map at the Congress of Vienna—notably Prussia’s control over the Rhineland and Westphalia—affected the incentives for policymakers to cooperate. The new borders were not endogenous. They were at odds with the strategy of Prussia, but followed from Britain’s intervention at Vienna regarding the Polish-Saxon question. For many small German states, the resulting borders changed the trade-off between the benefits from cooperation with Prussia and the costs of losing political control. Based on GIS data on Central Europe for 1818–1854 we estimate a simple model of the incentives to join an existing customs union. The model can explain the sequence of states joining the Prussian Zollverein extremely well. Moreover we run a counterfactual exercise: if Prussia would have succeeded with her strategy to gain the entire Kingdom of Saxony instead of the western provinces, the Zollverein would not have formed. We conclude that geography can shape institutional change. To put it different, as collateral damage to her intervention at Vienna,”’Britain unified Germany”’. JEL Codes: C31, F13, N73 ∗We would like to thank Robert C. Allen, Nicholas Crafts, Theresa Gutberlet, Theocharis N. Grigoriadis, Ulas Karakoc, Daniel Kreßner, Stelios Michalopoulos, Klaus Desmet, Florian Ploeckl, Kevin H. -

Geflügelpest in Thüringen Von Der Aufstallungspflicht Betroffene Gemeinden Mit Zugehörigen Ortsteilen Stand: 30.03.2021, 18.00 Uhr

www.thueringer-sozialministerium.de Geflügelpest in Thüringen Von der Aufstallungspflicht betroffene Gemeinden mit zugehörigen Ortsteilen Stand: 30.03.2021, 18.00 Uhr Albersdorf Oberroßla Albersdorf (bei Jena) Rödigsdorf Ascherhütte-Waldfrieden Schöten Alperstedt Sulzbach Alperstedt Utenbach Siedlung Alpenstedt Zottelstedt Altenberga Arnstadt Altenberga Rudisleben Altendorf (bei Jena) Bad Berka Greuda Bad Berka Schirnewitz Bergern Am Ettersberg Gutendorf Berlstedt Meckfeld (bei Bad Berka) Buttelstedt Schoppendorf Daasdorf Tiefengruben Großobringen Bad Klosterlausnitz Haindorf Bad Klosterlausnitz Heichelheim Köppe Hottelstedt Bad Sulza Kleinobringen Auerstedt Krautheim Bad Sulza Nermsdorf Flurstedt Ottmannshausen Gebstedt Ramsla Ködderitzsch Sachsenhausen Neustedt Schwerstedt Reisdorf Stedten (bei Berlstedt) Schwabsdorf (bei Rannstedt) Thalborn Sonnendorf Vippachedelhausen Wickerstedt Weiden Ballstedt Wohlsborn Ballstedt Apolda Bechstedtstraß Apolda Bechstedtsstraß Herressen Bibra Heusdorf Bibra (bei Kahla) Nauendorf Zwabitz Oberndorf (bei Apolda) Blankenhain 1 www.thueringer-sozialministerium.de Geflügelpest in Thüringen Von der Aufstallungspflicht betroffene Gemeinden mit zugehörigen Ortsteilen Stand: 30.03.2021, 18.00 Uhr Niedersynderstedt Voigtsmühle (Mannstedt) Bobeck Wiesenmühle (Hardisleben) Babeck Camburg Bocka Camburg Bocka (bei Gera) Döbrichau (bei Bad Kösen) Großbocka Dornburg (bei Jena) Hohe Reuth Dorndorf (bei Jena) Kleinbocka Dorndorf-Steudnitz Bremsnitz Hirschroda (bei Apolda) Bremsnitz (bei Stadtroda) Naschhausen (bei Dornburg) -

Übersicht Der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an Besonderen Orten

Übersicht der Philharmonischen Sommerkonzerte an besonderen Orten 25.06.2021 , 18 Uhr EISENACH in der Georgenkirche Eröffnungskonzert der Telemann-Tage „Zart gezupft und frisch gestrichen“ von Telemann zum jungen Mozart, mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch, Solistin Natalia Alencova, Mandoline (Tickets 20,-, erm. 15 Euro, www.telemann-eisenach.de) 27.06., 04.07. und 11.07.2021 jeweils 16 Uhr BAD SALZUNGEN im Garten der Musikschule Bratschenseptett „Ars nova“ der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Blechbläserquartett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach Bläserquintett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Eintritt frei, wir freuen uns über Spenden) 02.07.2021 19:30 Uhr EISENACH Landestheater Eisenach Eröffnungskonzert des Sommerfestivals des Landestheaters Eisenach mit dem Bläseroktett, Kontrabass und Schlagwerk der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (www.landestheater-eisenach.de, Touristinfo Eisenach, www.eventim.de) 03.07. und 17.07.2021, 17 Uhr BAD LIEBENSTEIN / SCHLOSSPARK ALTENSTEIN "Hofmusik zur Zeit Georgs I. von Sachsen-Meiningen" mit der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach, Solovioline/Leitung Alexej Barchevitch "Auf die Harmonie gesetzt" - Liebensteiner Bademusik mit dem Bläseroktett der Thüringen Philharmonie Gotha-Eisenach (Tickets über www.ticketshop-thueringen.de) 03.07. – 29.08.2021 SCHLOSSHOF OPEN AIR auf Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha mit verschiedenen Konzertprogrammen u.a. mit den Stargästen Ragna Schirmer und Martin Stadtfeld und vielen weiteren prominenten -

Betreuungsangebote - Nach § 45A (1) Nr

Angebote zur Unterstützung im Alltag - Betreuungsangebote - nach § 45a (1) Nr. 1 SGB XI Landkreis Ort Institution Strasse PLZ E-Mail Telefon Altenburger Land Altenburg AWO KV Altenburger Land e.V. "Selbständiges Humboldtstraße 12 04600 selbst.wohnen.abg@awo- 03447/558998 Wohnen im Alter" thueringen.de Altenburger Land Altenburg Gemeinschaftspraxis für Ergotherapie Katrin Jenke Gabelentzstr. 6c 04600 [email protected] 03447/895464 & Kati Kratzsch Altenburger Land Altenburg Horizonte Altenburg gGmbH Carl von Ossietzky Str. 04600 verwaltung@horizonte- 03447/514212 19 altenburg.de Altenburger Land Rositz Familienentlastender und unterstützender Dienst Parkstr. 1 4617 [email protected] 034498/819263 der Lebenshilfe Altenburg Eichsfeld Heiligenstadt Kath. Altenheime Eichsfeld gGmbH Hospitalstraße 1 37308 [email protected] 03606/661445 Eichsfeld Leinefelde - Lebenshilfe Worbis e.V. Ernemannstr. 6 37327 m.toepfer@lebenshilfe- 03605/200993 Worbis worbis.de Eichsfeld Marth Betreuungsdienst "Mit Freude am Leben" Am Anger 1 37318 betreuungsdienst- [email protected] 036081/61325 Erfurt Erfurt Schutzbund der Senioren und Vorrhuheständler Juri-Gagarin-Ring 64 99084 landesverband@seniorenschut 0361/2620735 Thüringen e.V. zbund.org Erfurt Erfurt Volkssolidarität Thüringen gGmbH Sozialstation O.-Schlemmer-Str. 1 99085 thueringen- 0361/654770 Erfurt [email protected] Erfurt Erfurt Deutschordens-Seniorenhaus gGmbH Sozialstation Vilniuser Str. 14 99089 [email protected] 0361-7720 Erfurt Erfurt Caritas Trägergesellschaft "St. Elisabeth" gGmbH Herderstraße 5 99096 st.elisabeth-erfurt@caritas- 0361/34460 Altenpflegezentrum cte.de Erfurt Erfurt Altenhilfe Sophienhaus gGmbH Martin-Luther- Blosenburgstr. 19 99096 [email protected] 0361/60068153 Haus Erfurt Erfurt Christophoruswerk Erfurt gGmbH - Ambulanter Allerheiligenstr. 8 99084 betreuungsdienst@christophor 0361/21001-550 Betreuungsdienst uswerk.de Erfurt Erfurt MIA, (Miteinander-Inklusiv-Anders), offene Brühler Str. -

Welcome to the Heart of Europe Find out | Invest | Reap the Benefits More Than 2,800 Advertising Boards in 16 German Cities Promoted Erfurt in 2014/2015

Welcome to the heart of Europe Find out | Invest | Reap the benefits More than 2,800 advertising boards in 16 German cities promoted Erfurt in 2014/2015. The confident message of this campaign? Erfurt is growing and continues to develop at a rapid pace. Inhalt Contents A city at the heart of the action. Erfurt is growing 2 In the heart of Germany. Location and transport links 4 A growing city. Projects for the future 6 Reinventing the heart of the city. ICE-City Erfurt 8 On fertile soil. Industry in Erfurt 10 Already bearing fruit. Leading companies 12 A region ready for take-off. The Erfurt economic area 16 A meeting place in the heart of Europe. Conferences and conventions 18 A passion for teaching and research. Campus Thuringia 20 A city to capture your heart. Life in Erfurt 24 Welcome to Erfurt. Advice and contact details 28 | 1 Erfurt is growing A city at the heart of the action. Land area of Erfurt: 269 km2 2 | Erfurt is growing Erfurt is going places! It’s not for nothing that the Cologne Insti- Most of the old town has been restored The many companies that have moved tute for Economic Research named Erfurt and combines medieval charm with the to Erfurt in recent years are making this among the ten most dynamic cities in buzz of an urban centre. possible. Germany in its 2014 rankings. You can see Erfurt, the regional capital of Thuringia, the changes everywhere and sense a spirit is a prime hotspot for development and, ‘Erfurt is growing’ is therefore the confi- of dynamism: all kinds of housing projects as such, offers the many young people who dent message that is currently being heard are being built across the city, new hotels choose to settle here excellent prospects all over Germany.