Spirited Defender – Unitarian Universalist World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Prophets, Spiritual Guides, Or Interfaith Traffic Directors?

Campus Prophets, Spiritual Guides, or Interfaith Traffic Directors? The Many Lives of College and University Chaplains The Luce Lectures on the Changing Role of Chaplains in American Higher Education Based on a Lecture Delivered on November 13, 2018 John Schmalzbauer Department of Religious Studies Missouri State University 901 South National Avenue Springfield, MO 65897 Email: [email protected] What roles do chaplains play in contemporary American higher education? Drawing on the National Study of Campus Ministries (2002-2008), this paper contrasts the post-war chaplaincy with its twenty-first century successor. While a relatively young occupation, the job of the college chaplain has shifted greatly over the past sixty years. Vastly different from the 1950s, the demographic profile of college chaplains has also changed, reflecting the growing presence of women clergy and the diversification of the American campus. Accompanying these shifts, changes in American religion have transformed the context of the profession. Though some things have remained the same (chaplains still preach, counsel, and preside over religious services), other things are very different. On the twenty-first century campus, chaplains have increasingly found themselves occupying the roles of campus prophets, spiritual guides, and interfaith traffic directors, a combination that did not exist in the mid-century chaplaincy.1 In chronicling these changes, it is helpful to compare accounts of post-war chaplaincy with the twenty-first century profession. Historian Warren Goldstein’s work on Yale University chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr. looms large in this comparison. For a whole generation of mainline Protestants, Coffin modeled an approach to chaplaincy that emphasized the public, prophetic components of the role, accompanying the Freedom Riders and protesting the Vietnam War. -

Living Tradition

Jesus Is Just Alright With Me April 13, 2014 Rev. John L. Saxon I This past year, Karla and I have been preaching a series of sermons on the six sources of what we call the “living tradition” of our Unitarian Universalist faith: direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder, affirmed in all cultures, that moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces that create and uphold life; words and deeds of prophetic women and men that challenge us to confront powers and structures of evil with justice, compassion, and the transforming power of love; wisdom from the world’s religions which inspires us in our ethical and spiritual life; humanist teachings that counsel us to heed the guidance of reason and the results of science, warning us against the idolatries of mind and spirit; and spiritual teachings of earth-centered traditions that celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature. But wait! That’s just five!!! There’s one more! I wonder what it could be? Let me think. (Pause.) Oh, now I remember! It’s Jewish and Christian teachings that call us to respond to God’s love by loving our neighbors as ourselves. II Now let’s face it. Claiming Jewish and Christian—especially Christian—teachings as one of the sources of Unitarian Universalism makes some UUs more than a little bit uncomfortable. There’s more than a little bit of truth in the joke that the only time you hear a UU say “Jesus Christ” is when she spills hot coffee in her lap during coffee hour on Sunday. -

Mindingbusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES

BULLETIN MindingBusiness the 4 ALUMNI-RUN COMPANIES WINTER 2018 In this ISSUE WINTER 2018 40 38 Minding the Business How Charlie Albert ’69, JJ Rademaekers ’89, AK Kennedy L’Heureux ’90, and James McKinnon ’87 achieved entrepreneurial success—and DEPARTMENTS became their own bosses 3 On Main Hall By Neil Vigdor ’95 8 Alumni Spotlight 16 Around the Pond 32 Sports 38 Larry Stone Tribute 66 Alumni Notes 58 106 Milestones How to Work Smarter, Not Harder The Moorhead Academic Center and Jon Willson ’82 in action By Julie Reiff 58 40 m Taft varsity football celebrates their 41–23 victory over Hotchkiss School on November 11. ROBERT FALCETTI Taft Bulletin / WINTER 2018 1 On Main Hall A WORD FROM HEADMASTER WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 WINTER 2018 Volume 88, Number 2 EDITOR Linda Hedman Beyus DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli THE RIGORS AND REWARDS OF ACCREDITATION ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Debra Meyers There are lots of ways schools improve. Boards plan strategically, heads and “We have hard ON THE COVER administrative teams examine and change practices, and faculty experiment PHOTOGRAPHY work to do, but it’s A model of a Chuggington® train—inspired by the Robert Falcetti and innovate. But for schools like Taft, there’s another critical way: the New children’s animated show of the same name—greets England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC) Accreditation Process. It’s a the glorious work readers on this issue’s cover! Read the feature on ALUMNI NOTES EDITOR pages 40–57 about four alumni who create and make really rigorous methodology that ensures accredited schools regularly reflect, Hillary Dooley on challenges different products, including toy/games designer plan, and innovate; and it’s this process Taft just finished. -

Minister's Musings

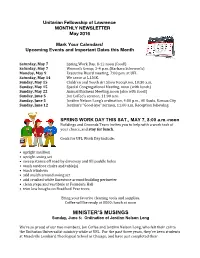

Unitarian Fellowship of Lawrence MONTHLY NEWSLETTER May 2016 Mark Your Calendars! Upcoming Events and Important Dates this Month Saturday, May 7 Spring Work Day, 8-12 noon (food!) Saturday, May 7 Women’s Group, 2-4 p.m. (Barbara Schowen’s) Monday, May 9 Executive Board meeting, 7:00 p.m. at UFL Saturday, May 14 We serve at L.I.N.K. Sunday, May 15 Children and Youth Art Show Reception, 10:30 a.m. Sunday, May 15 Special Congregational Meeting, noon (with lunch) Sunday, May 22 Annual Business Meeting, noon (also with food!) Sunday, June 5 Jon Coffee’s sermon, 11:00 a.m. Sunday, June 5 Jordinn Nelson Long’s ordination, 4:00 p.m., All Souls, Kansas City Sunday, June 12 Jordinn’s “Good-bye” sermon, 11:00 a.m. Reception following SPRING WORK DAY THIS SAT., MAY 7, 8:00 a.m.-noon Buildings and Grounds Team invites you to help with a work task of your choice, and stay for lunch. Goals for UFL Work Day include: • upright mailbox • upright swing set • sweep stones off road by driveway and fill puddle holes • wash outdoor chairs and table(s) • wash windows • add mulch around swing set • add crushed white limestone around building perimeter • clean steps and vestibule at Founders Hall • trim low boughs on Bradford Pear trees Bring your favorite cleaning tools and supplies. Coffee will be ready at 0800; lunch at noon MINISTER’S MUSINGS Sunday, June 5: Ordination of Jordinn Nelson Long We're so proud of our two members, Jon Coffee and Jordinn Nelson Long, who felt their call to the Unitarian Universalist ministry while at UFL. -

Works on Theology and Vocation

An Annotated Bibliography of Works Pertinent to Vocation and Values Works on Theology and Vocation: Title Author/Publisher Work Description A collection of theological essays from a multi- and interdisciplinary approach, stemming from Loyola University John Haughey, S. J., editor; 2003 Revisiting the Idea of Vocation: of Chicago’s participation in the The Catholic University of Theological Explorations Programs for the Theological America Press Exploration of Vocation. The volume includes essays written from Jewish and Islamic perspectives. Gilbert C. Meilander; 2000 Notre This collection offers a Working: Its Meaning and Its Dame Press comprehensive look at work by Limits different authors. Historical review of professional life in America and the impact of Work and Integrity: The Crisis William Sullivan; 1995 globalization, technology, and and Promise of Professionalism HarperCollins changing work patterns on in America professionals. The book promotes civic responsibilities for professionals, and commitments to the larger society. Guide to help people discover R. J. Ledier & D. A. Shapiro; Whistle While You Work and heed their callings, using 2001 Berrett-Koehler stories and exercises. Best-seller for twenty-five years— helps job hunters define their Richard N. Bolles; 2002 Ten What Color is Your Parachute? interests, experience, goals, and Speed Press state of mind, then points them in the direction of a suitable, satisfying and profitable career. Arguing that all work should have The Reinvention of Work: A dignity, Fox envisions a work Matthew Fox; 1995 Harper San New Vision of Livelihood for world in which intellect, heart, Francisco Our Time and health harmonize to celebrate the whole person. Drawing on interviews with fast- trackers, Albion shares how these Making a Life, Making a Living: Mark Albion; 2000 Warner Books men and women found the Reclaiming Your Purpose and courage and motivation to re- Passion in Business and Life create successful professional lives guided by passion. -

For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience

26 January 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com For Some, Religion Is Part of the College Experience Some students find new ways to explore and express religious attitudes, ideas and beliefs at college FAITH LAPIDUS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm Faith Lapidus. Today on our show, we play music from singer Lana Del Rey. We also answer a question from Burma about the way Americans elect a president. But, first we go to real college to hear how some students combine religion with their school life. College Religious Life FAITH LAPIDUS: Going to college is often a chance for young adults to explore ideas and beliefs different from those they grew up with. As they do, college students are finding new ways to express their beliefs. As we hear from 2 Christopher Cruise, American clergy say many young people are remaining true to their religious faith. (SOUND) CHRISTOPHER CRUISE: A traditional observance gives Indian students a chance to share their faith and culture with others. Many did that at this recent event, says Chandni Raja of the Hindu Student Organization at the University of Southern California. CHANDNI RAJA: "Meeting other groups on campus and trying to get that dialogue going, while also maintaining our own communities as a strong place where people can come together." Varun Soni works as dean of religious life at the University of Southern California. He says many students keep religion on their own terms. VARUN SONI: "They're more interested, I find, in making religion work for them as opposed to working for it. -

2015 Ministry Days WELCOME!

Unitarian Universalist Minsters Association 2015 Ministry Days June 22-24, 2015 — Oregon Convention Center (Portland, OR) WELCOME! We bid you welcome! Welcome to those who come with a twinkle in your eye and spring in your step, joyful to be a new minister. Welcome to those who are here for the very first time; and to those who stopped counting years ago. Welcome to those who come with a tired spirit and a heart broken from a year of disappointment. Welcome to those who come looking forward to a new chapter and ministry in life and those who are mourning that which just ended. Welcome to those extroverts who come eager for the energy only 650 colleagues can provide. Welcome to those introverts who come yearning for peace and solitude in the midst of the chaos. Welcome to those who come for words of inspiration and hope; and to those who come to sing and be held by music Welcome to those who we can touch and hug in Portland; to those in front of computer screens around the globe. Welcome… one and all. — Rev. Don Southworth All main events will be held in Ministry Days 2015 Schedule Portland Ballroom 254-255 Monday, June 22: DoubleTree Hotel ________________ Are you on Facebook? Chapter Leader Retreat (Adams/Jefferson) 8:00 AM - 5:00 PM Twitter? Instagram? Google+? Registration (Portland DoubleTree EMC: ) 2:00 PM - 7:30 PM Use #ministrydays when you Choir Rehearsal 4:30 PM - 5:30 PM post so our colleagues at home Reception/Welcome (Portland DoubleTree EMC) 7:30 PM - 10:00 PM can follow along! Follow the UUMA at: Tuesday, June 23: Oregon Convention Center _________ facebook.com/uuministers Registration Continues (Portland Ballroom Lobby) 7:30 AM - 5:00 PM and @UUMinAssoc on Spiritual Practices (See page 8) 7:30 AM - 8:15 AM Twitter Quiet Space (E147) 7:30 AM - 2:30 PM Have you signed up for Opening Worship — Including Child Dedication 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM Ministry Days text updates Snack Break 10:00 AM - 10:15 AM yet? Text @UUMinistersMD to 23559 to sign up! Staying Keynote: Rev. -

Scotty Mclennan Believes Great Works of Literature Offer Deeper Insight Than Do Business Case Studies Or Biographies of Busines

n his sermon on leo tolstoy’s the death In using literature to discuss ethics in business, text. Charles Geschke, who was one of the founders of Ivan Ilyich, the Rev. Scotty McLennan asks a which authors and works do you study? of Adobe, and who is an active practicing Roman tough question. If the title character is respected Some American works would include F. Scott Catholic, talks about how to do that in your business as a government official, if he is fair as a prosecu- Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and The Last Tycoon, life. I use a case study by a now-deceased business- tor and dutiful as a husband and father, why as Flannery O’Connor’s The Displaced Person and A person from Boston named Samina Qureshi, who Ihe lies dying at age 43 does he feel like a failure, Good Man is Hard to Find, Arthur Miller’s Death of was Muslim, and how she saw herself responsible for that his life hasn’t been “real”? The congregation a Salesman, Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!, Saul Bellow’s the spiritual as well as business life of employees of pondering that question isn’t necessarily seated in Seize the Day, and the Norwegian writer Henrik Ib- her design and architectural firm. pews, for the Rev. McLennan is a theologian not sen’s An Enemy of the People. A third course I teach is called “Global Business, only to the faithful but to students of business. On I also was interested in helping people think Religion, and National Culture.” If you’re going to do the faculty at Stanford Business School, he lectures about how to do business around the world, in dif- business in India, it behooves you to know something on ethics and spirituality, exploring how to recon- ferent cultural settings and with different religions about Hinduism, and in the UAE, Islam, in Japan, cile the pursuits of prosperity and spiritual growth. -

UUMA News the Newsletter of the Unitarian Universalist Ministers’ Association

UUMA News The Newsletter of the Unitarian Universalist Ministers’ Association From the President March 2002 — Dear Colleagues, Convo 2002 (p. 2) What a thrill it was to see so many beloved colleagues gathered for our 2002 convocation in Bir- E-Mail Aliases (p. 3) mingham. What a feast of lectures, worship, small groups and chance encounters! And how (p. 3) gratifying it was to see us take seriously our witness for social justice in the midst of our other EDGES of the Spirit plans. I hope that all of us, whether we were able to be there or not, join together to recognize the Public Witness Seminar (p. 3) debt of gratitude that we owe to the members of the Convo Planning Committee: Patricia Jimenez, Doug Morgan Strong, Susan Manker Seale, Bob Schaibly, Jane Bramadat, Scotty Ministerial Specialties (p. 4) Meek, and Chair Kirk Loadman Copeland. My hat is off to every one of them. As you will read elsewhere in this newsletter, videotapes and print copies of the lectures and many other events Journey Toward Wholeness (p. 5) are available; some of them would make wonderful congregational study materials and conversa- Gilbert Spirit Fund (p. 5) tion starters. I was heartened by the opportunity at Convo to get on the table several issues that have con- Sermon Awards (p. 6) cerned the Executive Committee for some time and have been circulating in the form of specula- tions and rumors. One of these is the nature of our ongoing connection between us as an interna- Notable Unitarians (p. 8) tional body of colleagues following the changes that are in process between the UUA and the UU Reflections on Prayer (p. -

Title Here P 1 Table of Contents

Title Here p 1 Table of Contents Welcome!.........................................................................1 Getting the Most Out of the Conference.................................2 Conference Overview........................................................4 Special Events...................................................................6 Plenary Sessions..............................................................10 Workshops: Sunday, October 25.........................................18 Workshops: Monday, October 26.......................................28 Workshops: Tuesday, October 27.......................................39 Thank You to Our Donors..................................................46 Thank You To Our NGO Sponsors........................................47 Conference Schedule........................................................48 Map of Norris......................................................back cover Welcome! p 1 Dear Friends, This conference allows us to feel the pulse of the interfaith movement. Your lives, projects and presence make up the beat and strength of that pulse. At this conference, you will learn from and be challenged by the workshops and speakers, but you will grow the most by engaging deeply with one another. Take time to hear each other’s stories. Encourage one another. Envision new ways of doing things together. If nothing else, harness the creative potential of our collective imagination. Many organizations have conferences, what will make this moment unique is what happens after. -

Developing Our Faith

Developing Our Faith Building Your Own Chalice Children Theology, Volume 1 A Unitarian Universalist Introduction, Second Edition Preschool Curriculum A Good Telling Richard Gilbert Katie Erslev Bringing Worship to Life with Based on the assumption that Based on the premise that children learn best through Story everyone is their own Kristin Maier theologian, this classic UU adult experience, this program helps This guide to storytelling in education program invites nurture spiritual growth, worship provides techniques for participants to develop their creativity and a sense of good storytelling, plus practice own personal credos community through imaginative exercises to help readers learn Item 1004 | $16.00 activities and rituals such as to employ them. Skinner House rhymes and finger plays. Item 5111 | $16.00 Building Your Own Item 1860 | $30.00 Theology, Volume 2 Around the Church, Around Exploring, Second Edition Come Sing a Song with Me the Year Richard Gilbert A Songbook for All Ages Edited by Melodie Feather Unitarian Universalism for Continues the credo Twenty-five of the most popular Kindergarten to Grade 2 development process by and accessible songs from Jan Evans-Till focusing on various theological Singing the Living Tradition and This year-long program helps questions to help participants Singing the Journey in simple young children understand the grow in their ability to arrangements for families, faith and practices of our UU understand and articulate their summer camps, RE and community. own belief systems multigenerational -

Revs. David and Teresa Schwartz

SENIOR MINISTERS OF THE FIRST UNITARIAN CHURCH OF CHICAGO founded 1836 A Service for the Ordination to the Unitarian Universalist Ministry of 1839 - 1844 Joseph Harrington, Jr. 1846 - 1849 William Adam Teresa Lynn Schwartz and David Richard Schwartz 1849 - 1857 Rush Rhees Shippen 1857 - 1859 George Noyes and their Installation as 19th & 20th Ministers of 1861 - 1864 Charles Thomas 1866 - 1874 Robert Laird Collier The First Unitarian Church of Chicago 1876 - 1881 Brooke Herford 1183 - 1891 David Utter 1891 - 1901 William Wallace Fenn 1901 - 1923 William Hansen Pulsford 1925 - 1944 Von Ogden Vogt 1944 - 1962 Leslie Pennington 1963 - 1968 Jack Kent 1969 - 1978 Jack Mendelsohn 1980 - 1986 Duke Gray 1988 - 1991 Tom Chula k 1993 - 1998 Terasa Cooley 1999 - 2011 Nina Grey WELCOME Heading Out Members, friends, family, neighbors, Philip Booth the reverend clergy, and visitors: welcome all who have come with joy Beyond here there’s no map. into this house of memory and hope How you get there is where loving our shared history, you’ll arrive; how, dawn by journeying together into the future. dawn, you can see your way clear: in ponds, sky, just as Whether you are here for the first time, woods you walk through give whether you have walked these stones for decades, to fields. And rivers: beyond you belong here this hour. all burning, you’ll cross on bridges you’ve long lugged with you. Whatever your route, go lightly, toward light. Once you give away all save necessity, all’s SERVICE OF ORDINATION AND INSTALLATION mostly well: what you used to believe you owned is nothing, nothing beside how you’ve come to feel.