Black Queer Placemaking in Subprime Baltimore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

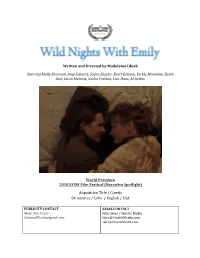

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Garveyism: a ’90S Perspective Francis E

New Directions Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 7 4-1-1991 Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective Francis E. Dorsey Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections Recommended Citation Dorsey, Francis E. (1991) "Garveyism: A ’90s Perspective," New Directions: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/newdirections/vol18/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Directions by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GARVEYISM A ’90s Perspective By Francis E. Dorsey Pan African Congress in Manchester, orn on August 17, 1887 in England in 1945 in which the delegates Jamaica, Marcus Mosiah sought the right of all peoples to govern Garvey is universally recog themselves and freedom from imperialist nized as the father of Pan control whether political or economic. African Nationalism. After Garveyism has taught that political power observing first-hand the in without economic power is worthless. Bhumane suffering of his fellow Jamaicans at home and abroad, he embarked on a mis The UNIA sion of racial redemption. One of his The corner-stone of Garvey’s philosophical greatest assets was his ability to transcend values was the establishment of the Univer myopic nationalism. His “ Back to Africa” sal Negro Improvement Association, vision and his ‘ ‘Africa for the Africans at UNIA, in 1914, not only for the promulga home and abroad” geo-political perspec tion of economic independence of African tives, although well before their time, are peoples but also as an institution and all accepted and implemented today. -

Racism and Discrimination As Risk Factors for Toxic Stress

Racism and Discrimination as Risk Factors for Toxic Stress April 28, 2021 ACEs Aware Mission To change and save lives by helping providers understand the importance of screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences and training providers to respond with trauma-informed care to mitigate the health impacts of toxic stress. 2 Agenda 1. Discuss social and environmental factors that lead to health disparities, as well as the impacts of racism and discrimination on public health across communities 2. Broadly discuss the role of racism and discrimination as risk factors for toxic stress and ACE Associated Health Conditions 3. Make the case to providers that implementing Trauma-Informed Care principles and ACE screening can help them promote health equity as part of supporting the health and wellbeing of their patients 3 Presenters Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH Chief Health Equity Officer, SVP, American Medical Association Ray Bignall, MD, FAAP, FASN Director, Kidney Health Advocacy & Community Engagement, Nationwide Children’s Hospital; Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine Roy Wade, MD, PhD, MPH Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania, Division of General Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia 4 Operationalizing Racial Justice Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH Chief Health Equity Officer, SVP American Medical Association Land and Labor Acknowledgement We acknowledge that we are all living off the stolen ancestral lands of Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. We acknowledge the extraction of brilliance, energy and life for labor forced upon people of African descent for more than 400 years. We celebrate the resilience and strength that all Indigenous people and descendants of Africa have shown in this country and worldwide. -

Zola.’ (AP) Song of the Summer

ARAB TIMES, THURSDAY, JULY 1, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Music Dacus sings young love Cat album falters at fi rst but ends strong By Mark Kennedy ot to be totally catty, but Doja Cat’s third album Nstarts poorly. The first four songs — “Woman,” “Naked,” “Payday” with Young Thug and “Get Into It (Yuh)” — are half-baked tunes mimicking beats and vocals from Nicki Minaj or Rihanna. None are note- worthy. It’s depressing. What happened to the artist behind 2019s “Hot Pink,” a sonic breath of fresh air? What happened to the Doja Cat whose electric performance of “Say So” at the Grammys was reminiscent of Missy Elliott’s futurism? Just wait. The fi fth song, “Need to Know,” is a superb, steamy sex tape of a song (with Dr. Luke co-writing and producing) and the sixth, “I Don’t Do Drugs” featuring Ariana Grande, is airy and confi dent with heav- enly harmonies. “Love to Dream” follows, a slice of dreamy pop, and then The Weeknd stops by on a terrifi c, slow-burning “You Right.” Cat The Cat is back. From then on, the 14-track “Planet Her” rights itself with whispery pop songs and the envelope-pushing “Options” with JID, climaxing with the awesome “Kiss Me More,” the previously released single with SZA that has a Gwen Stefani-ish refrain and must be considered a strong contender for This image released by A24 shows Riley Keough, (left), and Taylour Paige in a scene from ‘Zola.’ (AP) song of the summer. Despite the weak start, Doja Cat fulfi lls her promise on “Planet Her,” with an exciting, unpredictable style and a vocal ability that can switch from buttery sweet- Film ness to cutting raps. -

FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR

Southern California Public Radio- FCC Quarterly Programming Report Jan 1-March 31, 2017 KPCC-KUOR-KJAI-KVLA START TIME Duration min:sec Public Affairs Issue 1 Public Affairs Issue 2 Show & Narrative 1/2/2017 TAKE TWO: The Binge– 2016 was a terrible year - except for all the awesome new content that was Entertainment Industry available to stream. Mark Jordan Legan goes through the best that 2016 had to 9:42 8:30 offer with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: The Ride 2017– 2017 is here and our motor critic, Sue Carpenter, Transportation puts on her prognosticator hat to predict some of the automotive stories we'll be talking about in the new year 9:51 6:00 with Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Presidents and the Press– Presidential historian Barbara Perry says contention between a President Politics Media and the news media is nothing new. She talks with Alex Cohen about her advice for journalists covering the 10:07 10:30 Trump White House. TAKE TWO: The Wall– Political scientist Peter Andreas says building Trump's Immigration Politics wall might be easier than one thinks because hundreds of miles of the border are already lined with barriers. 10:18 12:30 He joins Alex Cohen. TAKE TWO: Prison Podcast– A podcast Law & is being produced out of San Quentin Media Order/Courts/Police State Prison called Ear Hustle. We hear some excerpts and A Martinez talks to 10:22 9:30 one of the producers, Nigel Poor. TAKE TWO: The Distance Between Us– Reyna Grande grew up in poverty in Books/ Literature/ Iguala, Mexico, left behind by her Immigration Authors parents who had gone north looking for a better life and she's written a memoir for young readers. -

Fresno-Commission-Fo

“If you are working on a problem you can solve in your lifetime, you’re thinking too small.” Wes Jackson I have been blessed to spend time with some of our nation’s most prominent civil rights leaders— truly extraordinary people. When I listen to them tell their stories about how hard they fought to combat the issues of their day, how long it took them, and the fact that they never stopped fighting, it grounds me. Those extraordinary people worked at what they knew they would never finish in their lifetimes. I have come to understand that the historical arc of this country always bends toward progress. It doesn’t come without a fight, and it doesn’t come in a single lifetime. It is the job of each generation of leaders to run the race with truth, honor, and integrity, then hand the baton to the next generation to continue the fight. That is what our foremothers and forefathers did. It is what we must do, for we are at that moment in history yet again. We have been passed the baton, and our job is to stretch this work as far as we can and run as hard as we can, to then hand it off to the next generation because we can see their outstretched hands. This project has been deeply emotional for me. It brought me back to my youthful days in Los Angeles when I would be constantly harassed, handcuffed, searched at gunpoint - all illegal, but I don’t know that then. I can still feel the terror I felt every time I saw a police cruiser. -

Black Capitalism’

Opinion The Real Roots of ‘Black Capitalism’ Nixon’s solution for racial ghettos was tax breaks and incentives, not economic justice. By Mehrsa Baradaran March 31, 2019 The tax bill President Trump signed into law in 2017 created an “opportunity zones” program, the details of which will soon be finalized. The program will provide tax cuts to investors to spur development in “economically distressed” areas. Republicans and Democrats stretching back to the Nixon administration have tried ideas like this and failed. These failures are well known, but few know the cynical and racist origins of these programs. The neighborhoods labeled “opportunity zones” are “distressed” because of forced racial segregation backed by federal law — redlining, racial covenants, racist zoning policies and when necessary, bombs and mob violence. These areas were black ghettos. So how did they come to be called “opportunity zones?” The answer lies in “black capitalism,” a forgotten aspect of Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy. Mr. Nixon's solution for racial ghettos was not economic justice, but tax breaks and incentives. This deft political move allowed him to secure the support of 2 white Southerners and to oppose meaningful economic reforms proposed by black activists. You can see how clever that political diversion was by looking at the reforms that were not carried out. After the Civil Rights Act, black activists and their allies pushed the federal government for race-specific economic redress. The “whites only” signs were gone, but joblessness, dilapidated housing and intractable poverty remained. In 1967, blacks had one-fifth the wealth of white families. ADVERTISEMENT Yet a white majority opposed demands for reparations, integration and even equal resources for schools. -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Spring 2018 34

The The James Weldon Johnson Institute James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference SPRING/SUMMER 2018 In this Issue Letter from the Director Meeting the Moment 2 About the 2017–2018 Visiting Scholars Amrita Chakrabarti Myers: The Freedom Writer 3 Ashanté Reese: Dreaming a More Just World 6 Ashley Brown: Illuminating Athletes’ Place in Society and History 9 Derek Handley: Sharing the History That Speaks to Him 11 Felipe Hinojosa: Church Takeovers and Their Impact on Latino Religion 13 Justin Hosbey: Back Home and Very Gainfully Employed 15 Kyera Singleton: Archival ‘Play’ Yields Dissertation Topic 18 Taína Figueroa: On the Road to Becoming a Latina Feminist Philosopher 20 Alison M. Parker: Righting a Historical Wrong 22 Taylor Branch Delivers JWJI Distinguished Lecture 24 Looking Back at the Race and Difference Colloquium Series 27 Major Programs Calendar: 2017–2018 32 Teaching Race and History: Institute Course Offerings, Spring 2018 34 1 The James Weldon Johnson Institute Director’s Letter: Meeting the Moment Dear Friends of the James Weldon Johnson beyond to disseminate important findings that Institute, can empower and uplift communities across the country. Thank you for your continued support. We have had an eventful and productive academic year and We cannot do this important work without your would like to use its end—and this newsletter—to support. We are always humbled at the number of reflect on where we have been and look forward people who faithfully support us by attending our to next year. events. And we are forever grateful for those who are able to sustain us financially. -

ED240217.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 240 217 UD 023 393 TITLE Selected Multicultural Instructional Materials. INSTITUTION Seattle School District 1, Wash.; Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Aug 83 NOTE 724p.; Light print. Published by the Office for Multicultural and Equity Education. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC29 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Class Activities; *Cultural Activities; Elementary Education; *Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Instructional Materials; *Multicultural Education IDENTIFIERS *Holidays ABSTRACT This is a compilation of ten multicultural instructional booklets that were prepared and published by the Seattle, Washington, School District. The first booklet, entitled "Selected Multi-ethnic/Multicultural Events and Personalities," lists and describes (1) major holidays and events celebrated in the United States, and (2) American ethnic minority and majority individuals and their achievements. Booklet 2, "Chinese New Year," contains background information and classroom activities about that holiday, as well as Korean and Vietnamese New Year's customs. Booklet 3 presents activities and assembly suggestions prepared to assist schools in commemorating January 15, the birthdate of Martin. Luther King, Jr. The information and activities in Booklet 4 focus on the celebration of Afro-American History Month. Booklet 5; "Lei Day," focuses on Hawaiian history, culture, and statehood. Booklet 6 is entitled "Cinco de Mayo," and presents information about the Mexican defeat of French troops in 1862, as well as other Mexican events and cultural activities. Booklet 7 centers around Japan and the Japanese holiday, "Children's Day." The Norwegian celebration "Styyende Mai" (Constitution Day, May 17), is described in Booklet 8, along with other information about and cultural activities from Norway.