The Deification of Imperial Women: Second-Century Contexts a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17Th-First Half of the 18Th Century

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Siedina, Giovanna. 2014. The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13065007 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2014 Giovanna Siedina All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Author: Professor George G. Grabowicz Giovanna Siedina The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century Abstract For the first time, the reception of the poetic legacy of the Latin poet Horace (65 B.C.-8 B.C.) in the poetics courses taught at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (17th-first half of the 18th century) has become the subject of a wide-ranging research project presented in this dissertation. Quotations from Horace and references to his oeuvre have been divided according to the function they perform in the poetics manuals, the aim of which was to teach pupils how to compose Latin poetry. Three main aspects have been identified: the first consists of theoretical recommendations useful to the would-be poets, which are taken mainly from Horace’s Ars poetica. -

SMITH Archeologia Classica.Pdf (384.1Kb)

NUOVA SERIE Rivista del Dipartimento di Scienze dell’antichità Sezione di Archeologia Fondatore: GIULIO Q. GIGLIOLI Direzione Scientifica MARIA CRISTINA BIELLA, ENZO LIPPOLIS, LAURA MICHETTI, GLORIA OLCESE, DOMENICO PALOMBI, MASSIMILIANO PAPINI, MARIA GRAZIA PICOZZI, FRANCESCA ROMANA STASOLLA, STEFANO TORTORELLA Direttore responsabile: DOMENICO PALOMBI Redazione: FABRIZIO SANTI, FRANCA TAGLIETTI Vol. LXVIII - n.s. II, 7 2017 «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER - ROMA Comitato Scientifico PIERRE GROS, SYBILLE HAYNES, TONIO HÖLSCHER, METTE MOLTESEN, STÉPHANE VERGER Il Periodico adotta un sistema di Peer-Review Archeologia classica : rivista dell’Istituto di archeologia dell’Università di Roma. - Vol. 1 (1949). - Roma : Istituto di archeologia, 1949. - Ill.; 24 cm. - Annuale. - Il complemento del titolo varia. - Dal 1972: Roma: «L’ERMA» di Bretschneider. ISSN 0391-8165 (1989) CDD 20. 930.l’05 ISBN CARTACEO 978-88-913-1563-2 ISBN DIGITALE 978-88-913-1567-0 ISSN 0391-8165 © COPYRIGHT 2017 - SAPIENZA - UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA Aut. del Trib. di Roma n. 104 del 4 aprile 2011 Volume stampato con contributo di Sapienza - Università di Roma INDICE DEL VOLUME LXVIII ARTICOLI AMBROGI A. (con un’appendice di FERRO C.), Un rilievo figurato di età tardo- repubblicana da un sepolcro dell’Appia antica ............................................... p. 143 BALDASSARRI P., Lusso privato nella tarda antichità: le piccole terme di Palazzo Valentini e un pavimento in opus sectile con motivi complessi...................... » 245 BARATTA G., Falere tardo-antiche ispaniche con quattro passanti angolari: aggiornamenti e ipotesi sulla funzionalità del tipo ......................................... » 289 BARBERA M., Prime ipotesi su una placchetta d’avorio dal Foro Romano .......... » 225 COATES-STEPHENS R., Statue museums in Late Antique Rome ........................... » 309 GATTI S., Tradizione ellenistica e sperimentazione italica: l’Aula Absidata nel foro di Praeneste ............................................................................................ -

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 History of Rome You Will Find in This Packet

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 A e History of Rome A You will find in this packet three different readings. 1) Augustus’ autobiography. which he had posted for all to read at the end of his life: the Res Gestae (“Deeds Accomplished”). 2) A few passages from Vergil’s Aeneid (the epic telling the story of Aeneas’ escape from Troy and journey West to found Rome. The passages from the Aeneid are A) prophecy of the glory of Rome told by Jupiter to Venus (Aeneas’ mother). B) A depiction of the prophetic scenes engraved on Aeneas’ shield by the god Vulcan. The most important part of this passage to read is the depiction of the Battle of Actium as portrayed on Aeneas’ shield. (I’ve marked the beginning of this bit on your handout). Of course Aeneas has no idea what is pictured because it is a scene from the future... Take a moment to consider how the Battle of Actium is portrayed by Vergil in this scene! C) In this scene, Aeneas goes down to the Underworld to see his father, Anchises, who has died. While there, Aeneas sees the pool of Romans waiting to be born. Anchises speaks and tells Aeneas about all of his descendants, pointing each of them out as they wait in line for their birth. 3) A passage from Horace’s “Song of the New Age”: Carmen Saeculare Important questions to ask yourself: Is this poetry propaganda? What do you take away about how Augustus wanted to be viewed, and what were some of the key themes that the poets keep repeating about Augustus or this new Golden Age? Le’,s The Au,qustan Age 195. -

The Gabii Project: Field School in Archaeology Rome, Italy June 16- July 20, 2019

The Gabii Project: Field School in Archaeology Rome, Italy June 16- July 20, 2019 About the Gabii Project We are an international archaeological initiative promoted by the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan. We have been excavating the Latin city of Gabii since 2007 in order to study the formation and growth of an ancient city-state that was both neighbor, and rival to, Rome in the first millennium BCE. Our research tackles questions about the emergence of zoning and of proper city blocks, street layouts and their relationship to city walls, definition of élite and commoner neighborhoods, development of monumental civic architecture, abandonment and repurposing of public and private areas, and much else, through the integration of spatial data, architecture and stratigraphy, and a wide variety of finds spanning from the Iron Age to the Late Roman periods. What you will learn • The archaeology of Rome and Latium, including guided trips to select sites and museums and off-site lectures • Excavation and interpretation of ancient Gabii • Digital, cutting edge recording techniques • Scientific processes, including environmental and biological analysis What is included • Program costs: $4,950 for first time volunteers/ $4,450 for returners. • Accommodations in vibrant Trastevere, Rome. • Insurance, equipment, local transportation, weekday lunches, select museum fees. • 24/7 logistical support. APPLY NOW! • Apartments include: kitchen facilities, washing machines, wireless internet. Fill out the online application at Not included: international flights http://gabiiproject.org/apply-now. Applications must be submitted by March 1st, 2019. Questions? Contact us [email protected] . -

Servius, Cato the Elder and Virgil

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository MEFRA – 129/1 – 2017, p. 85-100. Servius, Cato the Elder and Virgil Christopher SMITH C. Smith, British School at Rome, University of St Andrews, [email protected] This paper considers one of the most significant of the authors cited in the Servian tradition, Cato the Elder. He is cited more than any other historian, and looked at the other way round, Servius is a very important source for our knowledge of Cato. This paper addresses the questions of what we learn from Servius’ use of Cato, and what we learn about Virgil ? Servius, Cato the Elder, Virgil, Aeneas Cet article envisage la figure du principal auteur cite dans la tradition servienne, Caton l’Ancien. C’est l’historien le plus cité par Servius et, à l’inverse, Servius est une source très importante pour notre connaissance de Caton. Cet article revient sur l’utilisation de Caton par Servius et sur ce que Servius nous apprend sur Virgile. Servius, Catone l’Ancien, Virgile, Énée The depth of knowledge and understanding icance of his account of the beginnings of Rome. underpinning Virgil’s approach to Italy in the Our assumption that the historians focused on the Aeneid demonstrates that he was a profoundly earlier history and then passed rapidly over the learned poet ; and it was a learning which was early Republic is partly shaped by this tendency in clearly drawn on deep knowledge and under- the citing authorities2. -

Vestal Virgins of Rome: Images of Power

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference 2013, 24th Annual JWP Conference Apr 20th, 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM Vestal Virgins of Rome: Images Of Power Melissa Huang Illinois Wesleyan University Amanda Coles, Faculty Advisor Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc Part of the History Commons Huang, Melissa and Coles, Faculty Advisor, Amanda, "Vestal Virgins of Rome: Images Of Power" (2013). John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference. 3. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc/2013/oralpres5/3 This Event is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. 1 The Power of Representation: The Vestal Virgins of Rome Melissa Huang Abstract: The earliest archaeological and literary evidence suggest that the Vestal Virgins began as priestesses primarily responsible for religious fertility and purification rituals. Yet from humble beginnings, the Vestals were able to create a foothold in political life through the turbulence of the transition from Republic to Principate. -

Saevae Memorem Iunonis Ob Iram Juno, Veii, and Augustus

Acta Ant. Hung. 55, 2015, 167–178 DOI: 10.1556/068.2015.55.1–4.12 PATRICIA A. JOHNSTON SAEVAE MEMOREM IUNONIS OB IRAM JUNO, VEII, AND AUGUSTUS Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris Italiam, fato profugus, Laviniaque venit litora, multum ille et terris iactatus et alto vi superum saevae memorem Iunonis ob iram. Aen. I 1–4 Summary: A driving force in Vergil’s Aeneid is the hostility of Juno to the Trojans as they approach, and finally arrive in Italy. The epic in some ways mirrors the opposition encountered by Augustus as the new ruler of Rome. Juno’s opposition to the Trojans has its origin not only in Greek mythology, but in the his- tory of the local peoples of Italy with whom early Romans had to contend. From the outset of the poem she becomes the personification of these opposing forces. Once the Trojans finally reach mainland Italy, she sets in motion a long war, although the one depicted in the Aeneid was not as long as the real wars Ro- mans waged with the Latin League and with the many of the tribes of Italy, including the Veii. The reality of the wars Rome had to contend with are here compared to the relatively brief one depicted in the Aeneid, and the pacification of Juno reflects the merging of the different peoples of Rome with their subjugator. Key words: Juno, saeva, MARS acrostic, Etruscan Uni, evocatio, Veii, Fidenae, Aventinus, Gabii, Prae- neste, Tibur, Tanit, Saturnia, Apollo, Cumae and Hera, asylum, Athena, Aeneas, Anchises’ prophecy An important part of Augustan Myth is found in Vergil’s depiction of Juno, who is named in the opening lines of the epic and is a persistent presence throughout the poem. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard

Coriolanus and Fortuna Muliebris Roger D. Woodard Know, Rome, that all alone Marcius did fight Within Corioli gates: where he hath won, With fame, a name to Caius Marcius; these In honour follows Coriolanus. William Shakespeare, Coriolanus Act 2 1. Introduction In recent work, I have argued for a primitive Indo-European mythic tradition of what I have called the dysfunctional warrior – a warrior who, subsequent to combat, is rendered unable to function in the role of protector within his own society.1 The warrior’s dysfunctionality takes two forms: either he is unable after combat to relinquish his warrior rage and turns that rage against his own people; or the warrior isolates himself from society, removing himself to some distant place. In some descendent instantiations of the tradition the warrior shows both responses. The myth is characterized by a structural matrix which consists of the following six elements: (1) initial presentation of the crisis of the warrior; (2) movement across space to a distant locale; (3) confrontation between the warrior and an erotic feminine, typically a body of women who display themselves lewdly or offer themselves sexually to the warrior (figures of fecundity); (4) clairvoyant feminine who facilitates or mediates in this confrontation; (5) application of waters to the warrior; and (6) consequent establishment of societal order coupled often with an inaugural event. These structural features survive intact in most of the attested forms of the tradition, across the Indo-European cultures that provide us with the evidence, though with some structural adjustment at times. I have proposed that the surviving myths reflect a ritual structure of Proto-Indo-European date and that descendent ritual practices can also be identified. -

Vespasian's Apotheosis

VESPASIAN’S APOTHEOSIS Andrew B. Gallia* In the study of the divinization of Roman emperors, a great deal depends upon the sequence of events. According to the model of consecratio proposed by Bickermann, apotheosis was supposed to be accomplished during the deceased emperor’s public funeral, after which the senate acknowledged what had transpired by decreeing appropriate honours for the new divus.1 Contradictory evidence has turned up in the Fasti Ostienses, however, which seem to indicate that both Marciana and Faustina were declared divae before their funerals took place.2 This suggests a shift * Published in The Classical Quarterly 69.1 (2019). 1 E. Bickermann, ‘Die römische Kaiserapotheosie’, in A. Wlosok (ed.), Römischer Kaiserkult (Darmstadt, 1978), 82-121, at 100-106 (= Archiv für ReligionswissenschaftW 27 [1929], 1-31, at 15-19); id., ‘Consecratio’, in W. den Boer (ed.), Le culte des souverains dans l’empire romain. Entretiens Hardt 19 (Geneva, 1973), 1-37, at 13-25. 2 L. Vidman, Fasti Ostienses (Prague, 19822), 48 J 39-43: IIII k. Septembr. | [Marciana Aug]usta excessit divaq(ue) cognominata. | [Eodem die Mati]dia Augusta cognominata. III | [non. Sept. Marc]iana Augusta funere censorio | [elata est.], 49 O 11-14: X[— k. Nov. Fausti]na Aug[usta excessit eodemq(ue) die a] | senatu diva app[ellata et s(enatus) c(onsultum) fact]um fun[ere censorio eam efferendam.] | Ludi et circenses [delati sunt. — i]dus N[ov. Faustina Augusta funere] | censorio elata e[st]. Against this interpretation of the Marciana fragment (as published by A. Degrassi, Inscr. It. 13.1 [1947], 201) see E. -

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 Am

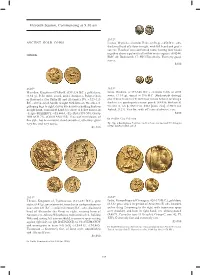

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30 am 2632* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Lesbos, Mytilene, electrum Hekte (2.56 g), c.450 B.C., obv. diademed head of a Satyr to right, with full beard and goat's ear, rev. Heads of two confronted rams, butting their heads together, above a palmette all within incuse square, (S.4244, GREEK BMC 40. Bodenstedt 37, SNG Fitz.4340). Fine/very good, scarce. $300 2630* 2633* Macedon, Kingdom of Philip II, (359-336 B.C.), gold stater, Ionia, Phokaia, (c.477-388 B.C.), electrum hekte or sixth (8.64 g), Pella mint, struck under Antipater, Polyperchon stater, (2.54 g), issued in 396 B.C. [Bodenstedt dating], or Kassander (for Philip III and Alexander IV), c.323-315 obv. female head to left, with hair in bun behind, wearing a B.C., obv. head of Apollo to right with laureate wreath, rev. diadem, rev. quadripartite incuse punch, (S.4530, Bodenstedt galloping biga to right, driven by charioteer holding kentron 90 (obv. h, rev. φ, SNG Fitz. 4563 [same dies], cf.SNG von in right hand, reins in left hand, bee above A below horses, in Aulock 2127). Very fi ne with off centred obverse, rare. exergue ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΥ, (cf.S.6663, cf.Le Rider 594-598, Group $400 III B (cf.Pl.72), cf.SNG ANS 255). Traces of mint bloom, of Ex Geoff St. Clair Collection. fi ne style, has been mounted and smoothed, otherwise good very fi ne and very scarce. The type is known from 7 obverse and 6 reverse dies and only 35 examples of type known to Bodenstedt.