GEE Paper 144 Portugal in the Global Innovation Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unescap Working Paper Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index

WP/09/02 UNESCAP WORKING PAPER FILLING GAPS IN THE HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: FINDINGS FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC David A. Hastings Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings from Asia and the Pacific David A. Hastings Series Editor: Amarakoon Bandara Economic Affairs Officer Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific United Nations Building, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, Thailand Email: [email protected] WP/09/02 UNESCAP Working Paper Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings for Asia and the Pacific Prepared by David A. Hastings∗ Authorized for distribution by Aynul Hasan February 2009 Abstract The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or carrying the endorsement of the United Nations. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. This publication has been issued without formal editing. This paper reports on the geographic extension of the Human Development Index from 177 (a several-year plateau in the United Nations Development Programme's HDI) to over 230 economies, including all members and associate members of ESCAP. This increase in geographic coverage makes the HDI more useful for assessing the situations of all economies – including small economies traditionally omitted by UNDP's Human Development Reports. The components of the HDI are assessed to see which economies in the region display relatively strong performance, or may exhibit weaknesses, in those components. -

The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life

Student Resource XIV The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life The ‘Human Development Index (HDI) is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development’ (UNDP). It is a measure closely related to quality of life, and is used to compare two or more countries. The United Nations developed the HDI based on three main dimensions: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living (see Image below). Figure 1: Indicators of HDI Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi In 2015, the United States ranked 8th among all countries in Human Development, ranking behind countries like Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany and Ireland (UNDP, 2015). The closer a country is to 1.0 on the HDI index, the better its standing in regards to human development. Maps of HDI ranking reveal regional patterns, such as the low HDI in Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2). Figure 2. The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) rankings for 2014 17 Use Student Resource XIII, Measuring Quality of Life Country Statistics to answer the following questions: 1. Categorize the countries into three groups based on their GNI PPP (US$), which relates to their income. List them here. High Income: Medium Income: Low Income: 2. Is there a relationship between income and any of the other statistics listed in the table, such as access to electricity, undernourishment, or access to physicians (or others)? Describe at least two patterns here. 3. There are several factors we can look at to measure a country's quality of life. -

The Connenction Between Global Innovation Index and Economic Well-Being Indexes

Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce – APSTRACT University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Debrecen SCIENTIFIC PAPER DOI: 10.19041/APSTRACT/2019/3-4/11 THE CONNENCTION BETWEEN GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX AND ECONOMIC WELL-BEING INDEXES Szlobodan Vukoszavlyev University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: We study the connection of innovation in 126 countries by different well-being indicators and whether there are differences among geographical regions with respect to innovation index score. We approach and define innovation based on Global Innovation Index (GII). The following well-being indicators were emphasized in the research: GDP per capita measured at purchasing power parity, unemployment rate, life expectancy, crude mortality rate, human development index (HDI). Innovation index score was downloaded from the joint publication of 2018 of Cornell University, INSEAD and WIPO, HDI from the website of the UN while we obtained other well-being indicators from the database of the World Bank. Non-parametric hypothesis testing, post-hoc tests and linear regression were used in the study. We concluded that there are differences among regions/continents based on GII. It is scarcely surprising that North America is the best performer followed by Europe (with significant differences among countries). Central and South Asia scored the next places with high standard deviation. The following regions with significant backwardness include North Africa, West Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean Area, Central and South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Regions lagging behind have lower standard deviation, that is, they are more homogeneous therefore there are no significant differences among countries in the particular region. -

The Human Development Index (HDI)

Contribution to Beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Name of the indicator/method: The Human Development Index (HDI) Summary prepared by Amie Gaye: UNDP Human Development Report Office Date: August, 2011 Why an alternative measure to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) The limitation of GDP as a measure of a country’s economic performance and social progress has been a subject of considerable debate over the past two decades. Well-being is a multidimensional concept which cannot be measured by market production or GDP alone. The need to improve data and indicators to complement GDP is the focus of a number of international initiatives. The Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission1 identifies at least eight dimensions of well-being—material living standards (income, consumption and wealth), health, education, personal activities, political voice and governance, social connections and relationships, environment (sustainability) and security (economic and physical). This is consistent with the concept of human development, which focuses on opportunities and freedoms people have to choose the lives they value. While growth oriented policies may increase a nation’s total wealth, the translation into ‘functionings and freedoms’ is not automatic. Inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth, unemployment, and disparities in access to public goods and services such as health and education; are all important aspects of well-being assessment. What is the Human Development Index (HDI)? The HDI serves as a frame of reference for both social and economic development. It is a summary measure for monitoring long-term progress in a country’s average level of human development in three basic dimensions: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. -

Technical Notes

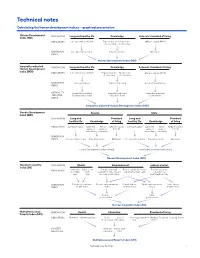

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity

A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity Discussion Paper for the International Congress on Ethnobiology University of Kent, U.K., June 2004 David Harmon and Jonathan Loh DRAFT DISCUSSION PAPER: DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE The purpose of this paper is to draw comments from as wide a range of reviewers as possible. Terralingua welcomes your critiques, leads for additional sources of information, and other suggestions for improvements. Address for comments: David Harmon c/o The George Wright Society P.O. Box 65 Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA [email protected] or Jonathan Loh [email protected] CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 BACKGROUND 6 Conservation in concert 6 What is biocultural diversity? 6 The Index of Biocultural Diversity: overview 6 Purpose of the IBCD 8 Limitations of the IBCD 8 Indicators of BCD 9 Scoring and weighting of indicators 10 Measuring diversity: some technical and theoretical considerations 11 METHODS 13 Overview 13 Cultural diversity indicators 14 Biological diversity indicators 16 Calculating the IBCD components 16 RESULTS 22 DISCUSSION 25 Differences among the three index components 25 The world’s “core regions” of BCD 29 Deepening the analysis: trend data 29 Deepening the analysis: endemism 32 CONCLUSION 33 Uses of the IBCD 33 Acknowledgments 33 APPENDIX: MEASURING CULTURAL DIVERSITY—GREENBERG’S 35 INDICES AND ELFs REFERENCES 42 2 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. IBCD-RICH, a biocultural diversity richness index. 46 Table 2. IBCD-AREA, an areal biocultural diversity index. 51 Table 3. IBCD-POP, a per capita biocultural diversity index. 56 Table 4. Highest 15 countries in IBCD-RICH and its component 61 indicators. -

Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-Country Evidence

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-country evidence Tripathi, Sabyasachi National Research University Higher School of Economics 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97474/ MPRA Paper No. 97474, posted 16 Dec 2019 14:18 UTC Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross- country evidence Dr. Sabyasachi Tripathi Postdoctoral Research Fellow Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge National Research University Higher School of Economics 20 Myasnitskaya St., 101000, Moscow, Russia Email: [email protected] Abstract: The present study assesses the impact of urbanization on the value of country-level Human Development Index (HDI), using random effect Tobit panel data estimation from 1990 to 2017. Urbanization is measured by the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, urban population growth rate, percentage of the population living in million-plus agglomeration, and the largest city of the country. Analyses are also separated by high income, upper middle income, lower middle income, and low-income countries. We find that, overall; the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, and percentage of urban population living in the million-plus agglomerations have a positive effect on the value of HDI with controlling for other important determinants of the HDI. On the other hand, urban population growth rate and percentage of the population residing in the largest cities have a negative effect on the value of HDI. Finally, we suggest that the promotion of urbanization is essential to achieving a higher level of HDI. The improvement of the percentage of urbanization is most important than other measures of urbanization. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 128 International Scientific Conference "Far East Con" (ISCFEC 2020) Cross-Country Comparison of the Level and Quality of Life of the Population: Modern Methods and Approaches P A Krasnokutskiy1, S S Zmiyak1, A M Kazakova1 1Department of World Economy and International Economic Relations, Don State Technical University, Gagarina sq. 1, Rostov-on-Don 344000, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Cross-country comparison of the level and quality of life at the present stage is implemented using a fairly significant number of indicators. However, certain ratings evaluate only certain parameters of the country's socio-economic development, level and quality of life. In this paper, based on the studies conducted by the authors, the methodological features of various indicators are characterized and their classification is carried out in accordance with four criteria: calculation frequency; measuring scale; coverage of world's economies; time lag. A comprehensive analysis of the socio-economic development of Russia is carried out using the ratings selected by the authors. The shortcomings of the proposed complex approach, as well as the author’s vision statement of the influence of these shortcomings on the final result are formulated. A comparison is made between Russia and the leading countries within the framework of the ratings used, as well as in dynamics with previously achieved positions. 1. Introduction The problem of cross-country comparison of the level and quality of life of the population at the present stage consists of multiple aspects. Despite the traditionally established approach, according to which cross-country comparisons are based on assessing the level of socio-economic development by calculation of GDP per capita, there are a number of alternative concepts designed to substantially supplement and expand this approach, as well as to focus on those aspects that are beyond the scope of its application. -

OECD Economic Surveys: Iceland 2021

OECD Economic Surveys Iceland OVERVIEW http://www.oecd.org/economy/iceland-economic-snapshot/ This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. OECD Economic Surveys: Iceland© OECD 2021 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected] of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 3 Table of contents Executive summary 8 1 Key policy insights 13 The economy is recovering 15 Monetary policy has been eased in response to the Covid-19 crisis 21 The financial system is considered to be sound but vigilance is warranted 23 Fiscal policy is supporting the economy 26 Policies to increase productivity and employment 33 References 42 FIGURES Figure 1. -

Population Dynamics and Human Development Indices in Selected African Countries: Trends and Levels

Population Dynamics and Human Development Indices in Selected African Countries: Trends and Levels By Nader Motie Haghshenas, MA, Arezo Sayyadi, MA, Sahel Taherianfard, MA , & Nahid Salehi, MA Population Studies and Research Center for Asia and the Pacific Tehran, IRAN Submitted to UAPS, 5th African Population Conference, Arusha, Tanzania, 10-14 December 2007 Abstract The low level of Human development Index (HDI) in African's countries has been affected by high population growth rate. World statistics show that African countries are in low level of HDI ranking, so that HDI for these countries in 2004 was 0.43 and the annual growth rate for 1975-2004 was % 2.7. In contrast in the other regions at high HDI ranking, HDI and annual growth rate were 0.89 and % 1.1, respectively. The aim of this study is to investigate the trends and levels of demographic variables and HDI in Niger, Sudan, Egypt and Morocco during 1975-2005. These are Muslim-majority countries (refer to countries in which Muslims constitute more than 50 percent of the total population). Data are taken from the United Nations Population Division and Human Development Report (HDR) for 2006. The results explained that there were differences in terms of population growth rates, fertility and mortality indices by their HDI ranking. The life expectancy and HDI have increased drastically and changed in selected African countries. On the other hand, population health indices among these countries, confirms a progress in medical care system. Yet, the level and trend of these indices are facing challenges. 2 Introduction Throughout history a variety of circumstances has proved to bring about unexpected changes in population trends. -

32Nd International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology

Human development indices Human Development Inequality-adjusted Gender Development Gender Inequality Multidimensional Index HDI Index Index Poverty Indexa Overall loss Difference from HDRO Value Value (%) HDI rankb Value Groupc Value Rank specificationsd Year and surveye HDI rank 2014 2014 2014 2014 2014 2014 2014 2014 Value 2005–2014 VERY HIGH HUMAN DEVELOPMENT 1 Norway 0.944 0.893 5.4 0 0.996 1 0.067 9 .. .. 2 Australia 0.935 0.858 8.2 –2 0.976 1 0.110 19 .. .. 3 Switzerland 0.930 0.861 7.4 0 0.950 2 0.028 2 .. .. 4 Denmark 0.923 0.856 7.3 –1 0.977 1 0.048 4 .. .. 5 Netherlands 0.922 0.861 6.6 3 0.947 3 0.062 7 .. .. 6 Germany 0.916 0.853 6.9 0 0.963 2 0.041 3 .. .. 6 Ireland 0.916 0.836 8.6 –3 0.973 2 0.113 21 .. .. 8 United States 0.915 0.760 17.0 –20 0.995 1 0.280 55 .. .. 9 Canada 0.913 0.832 8.8 –2 0.982 1 0.129 25 .. .. 9 New Zealand 0.913 .. .. .. 0.961 2 0.157 32 .. .. 11 Singapore 0.912 .. .. .. 0.985 1 0.088 13 .. .. 12 Hong Kong, China (SAR) 0.910 .. .. .. 0.958 2 .. .. .. .. 13 Liechtenstein 0.908 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 Sweden 0.907 0.846 6.7 3 0.999 1 0.055 6 .. .. 14 United Kingdom 0.907 0.829 8.6 –2 0.965 2 0.177 39 .. .. 16 Iceland 0.899 0.846 5.9 4 0.975 1 0.087 12 . -

How Do We Measure Standard of Living?

HOW DO WE MEASURE “standard of livin For most of us, standard of living is a know-it-when-I-see-it concept. We might not be able to express it in precise terms, but we think we know it when we see it. Ask us to define it, and we’ll reel off a list of things we associate with living well: a nice car, a pleasant place to live, clothes, furniture, appliances, food, vacations, maybe even education. Ask us to measure it, and we’ll probably look at whether or not we’re “doing better” than our parents. Yet there is a generally accepted measure for standard of living: average real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Let’s break it down piece by piece: • GDP measures annual economic output — the total value of new goods and services produced within a country’s borders. • Real GDP is the inflation-adjusted value. • Average GDP per capita tells us how big each person’s share of GDP would be if we were to divide the total into equal portions. In effect, we take the value of all goods and services produced within a country’s borders, adjust for inflation, and divide by the total population. If average real GDP per capita is increasing, there’s a strong likelihood that: (a) more goods and services are available to consumers, and (b) con- sumers are in a better position to buy them. And while buying more things won’t necessarily help us find true happiness, true love, or true enlighten- ment, it is a pretty good indicator of our material standard of living.