How Do We Measure Standard of Living?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unescap Working Paper Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index

WP/09/02 UNESCAP WORKING PAPER FILLING GAPS IN THE HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: FINDINGS FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC David A. Hastings Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings from Asia and the Pacific David A. Hastings Series Editor: Amarakoon Bandara Economic Affairs Officer Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific United Nations Building, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, Thailand Email: [email protected] WP/09/02 UNESCAP Working Paper Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings for Asia and the Pacific Prepared by David A. Hastings∗ Authorized for distribution by Aynul Hasan February 2009 Abstract The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or carrying the endorsement of the United Nations. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. This publication has been issued without formal editing. This paper reports on the geographic extension of the Human Development Index from 177 (a several-year plateau in the United Nations Development Programme's HDI) to over 230 economies, including all members and associate members of ESCAP. This increase in geographic coverage makes the HDI more useful for assessing the situations of all economies – including small economies traditionally omitted by UNDP's Human Development Reports. The components of the HDI are assessed to see which economies in the region display relatively strong performance, or may exhibit weaknesses, in those components. -

Standard of Living in America Today

STANDARD OF LIVING IN AMERICA TODAY Standard of Living is one of the three areas measured by the American Human Development Index, along with health and education. Standard of living is measured using median personal earnings, the wages and salaries of all workers 16 and over. While policymakers and the media closely track Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and judge America’s progress by it, the American Human Development Index tracks median personal earnings, a better gauge of ordinary Americans’ standard of living. The graph below chronicles two stories of American economic history over the past 35 years. One is the story of extraordinary economic growth as told by GDP; the other is a story of economic stagnation as told by earnings, which have barely budged since 1974 (both in constant dollars). GDP vs. Median Earnings: Change Since 1974 STRIKING FINDINGS IN STANDARD OF LIVING FROM THE MEASURE OF AMERICA 2010-2011: The Measure of America 2010-2011 explores the median personal earnings of various groups—by state, congressional district, metro area, racial/ethnic groups, and for men and women—and reveals alarming gaps that threaten the long-term well-being of our nation: American women today have higher overall levels of educational attainment than men. Yet men earn an average of $11,000 more. In no U.S. states do African Americans, Latinos, or Native Americans earn more than Asian Americans or whites. By the end of the 2007-9 recession, unemployment among the bottom tenth of U.S. households, those with incomes below $12,500, was 31 percent, a rate higher than unemployment in the worst year of the Great Depression; for households with incomes of $150,000 and over, unemployment was just over 3 percent, generally considered as full employment. -

An Evaluation of Poverty Prevalence in China: New Evidence from Four

An Evaluation of Poverty Prevalence in China: New Evidence from Four Recent Surveys Chunni ZHANG, Qi XU, Xiang ZHOU, Xiaobo ZHANG, Yu XIE Abstract In this paper, we calculate and compare the poverty incidence rate in China using four nationally representative surveys: the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS, 2010), the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS, 2010), the Chinese Household Finance Survey (CHFS, 2011), and the Chinese Household Income Project (CHIP, 2007). Using both international and official domestic poverty standards, we show that poverty prevalence at the national, rural, and urban levels based on the CFPS, CGSS and CHFS are much higher than official estimation and those based on the CHIP. The study highlights the importance of using independent datasets to validate official statistics of public and policy concern in contemporary China. 1 An Evaluation of Poverty Prevalence in China: New Evidence from Four Recent Surveys Since the economic reform began in 1978, China’s economic growth has not only greatly improved the average standard of living in China but also been credited with lifting hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty. According to one report (Ravallion and Chen, 2007), the poverty rate dropped from 53% in 1981 to 8% in 2001. Because of the vast size of the Chinese population, even a seemingly low poverty rate of 8% implies that there were still more than 100 million Chinese people living in poverty, a sizable subpopulation exceeding the national population of the Philippines and falling slightly short of the total population of Mexico. Hence, China still faces an enormous task in eradicating poverty. -

The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life

Student Resource XIV The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life The ‘Human Development Index (HDI) is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development’ (UNDP). It is a measure closely related to quality of life, and is used to compare two or more countries. The United Nations developed the HDI based on three main dimensions: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living (see Image below). Figure 1: Indicators of HDI Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi In 2015, the United States ranked 8th among all countries in Human Development, ranking behind countries like Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany and Ireland (UNDP, 2015). The closer a country is to 1.0 on the HDI index, the better its standing in regards to human development. Maps of HDI ranking reveal regional patterns, such as the low HDI in Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2). Figure 2. The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) rankings for 2014 17 Use Student Resource XIII, Measuring Quality of Life Country Statistics to answer the following questions: 1. Categorize the countries into three groups based on their GNI PPP (US$), which relates to their income. List them here. High Income: Medium Income: Low Income: 2. Is there a relationship between income and any of the other statistics listed in the table, such as access to electricity, undernourishment, or access to physicians (or others)? Describe at least two patterns here. 3. There are several factors we can look at to measure a country's quality of life. -

The Connenction Between Global Innovation Index and Economic Well-Being Indexes

Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce – APSTRACT University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Debrecen SCIENTIFIC PAPER DOI: 10.19041/APSTRACT/2019/3-4/11 THE CONNENCTION BETWEEN GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX AND ECONOMIC WELL-BEING INDEXES Szlobodan Vukoszavlyev University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: We study the connection of innovation in 126 countries by different well-being indicators and whether there are differences among geographical regions with respect to innovation index score. We approach and define innovation based on Global Innovation Index (GII). The following well-being indicators were emphasized in the research: GDP per capita measured at purchasing power parity, unemployment rate, life expectancy, crude mortality rate, human development index (HDI). Innovation index score was downloaded from the joint publication of 2018 of Cornell University, INSEAD and WIPO, HDI from the website of the UN while we obtained other well-being indicators from the database of the World Bank. Non-parametric hypothesis testing, post-hoc tests and linear regression were used in the study. We concluded that there are differences among regions/continents based on GII. It is scarcely surprising that North America is the best performer followed by Europe (with significant differences among countries). Central and South Asia scored the next places with high standard deviation. The following regions with significant backwardness include North Africa, West Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean Area, Central and South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Regions lagging behind have lower standard deviation, that is, they are more homogeneous therefore there are no significant differences among countries in the particular region. -

The Human Development Index (HDI)

Contribution to Beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Name of the indicator/method: The Human Development Index (HDI) Summary prepared by Amie Gaye: UNDP Human Development Report Office Date: August, 2011 Why an alternative measure to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) The limitation of GDP as a measure of a country’s economic performance and social progress has been a subject of considerable debate over the past two decades. Well-being is a multidimensional concept which cannot be measured by market production or GDP alone. The need to improve data and indicators to complement GDP is the focus of a number of international initiatives. The Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission1 identifies at least eight dimensions of well-being—material living standards (income, consumption and wealth), health, education, personal activities, political voice and governance, social connections and relationships, environment (sustainability) and security (economic and physical). This is consistent with the concept of human development, which focuses on opportunities and freedoms people have to choose the lives they value. While growth oriented policies may increase a nation’s total wealth, the translation into ‘functionings and freedoms’ is not automatic. Inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth, unemployment, and disparities in access to public goods and services such as health and education; are all important aspects of well-being assessment. What is the Human Development Index (HDI)? The HDI serves as a frame of reference for both social and economic development. It is a summary measure for monitoring long-term progress in a country’s average level of human development in three basic dimensions: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. -

The Economic Foundations of Authoritarian Rule

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 The conomicE Foundations of Authoritarian Rule Clay Robert Fuller University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fuller, C. R.(2017). The Economic Foundations of Authoritarian Rule. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4202 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECONOMIC FOUNDATIONS OF AUTHORITARIAN RULE by Clay Robert Fuller Bachelor of Arts West Virginia State University, 2008 Master of Arts Texas State University, 2010 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2014 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: John Hsieh, Major Professor Harvey Starr, Committee Member Timothy Peterson, Committee Member Gerald McDermott, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright Clay Robert Fuller, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION for Henry, Shannon, Mom & Dad iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks goes to God, the unconditional love and support of my wife, parents and extended family, my dissertation committee, Alex, the institutions of the United States of America, the State of South Carolina, the University of South Carolina, the Department of Political Science faculty and staff, the Walker Institute of International and Area Studies faculty and staff, the Center for Teaching Excellence, undergraduate political science majors at South Carolina who helped along the way, and the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. -

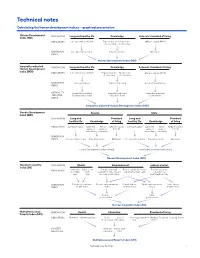

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity

A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity Discussion Paper for the International Congress on Ethnobiology University of Kent, U.K., June 2004 David Harmon and Jonathan Loh DRAFT DISCUSSION PAPER: DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE The purpose of this paper is to draw comments from as wide a range of reviewers as possible. Terralingua welcomes your critiques, leads for additional sources of information, and other suggestions for improvements. Address for comments: David Harmon c/o The George Wright Society P.O. Box 65 Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA [email protected] or Jonathan Loh [email protected] CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 BACKGROUND 6 Conservation in concert 6 What is biocultural diversity? 6 The Index of Biocultural Diversity: overview 6 Purpose of the IBCD 8 Limitations of the IBCD 8 Indicators of BCD 9 Scoring and weighting of indicators 10 Measuring diversity: some technical and theoretical considerations 11 METHODS 13 Overview 13 Cultural diversity indicators 14 Biological diversity indicators 16 Calculating the IBCD components 16 RESULTS 22 DISCUSSION 25 Differences among the three index components 25 The world’s “core regions” of BCD 29 Deepening the analysis: trend data 29 Deepening the analysis: endemism 32 CONCLUSION 33 Uses of the IBCD 33 Acknowledgments 33 APPENDIX: MEASURING CULTURAL DIVERSITY—GREENBERG’S 35 INDICES AND ELFs REFERENCES 42 2 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. IBCD-RICH, a biocultural diversity richness index. 46 Table 2. IBCD-AREA, an areal biocultural diversity index. 51 Table 3. IBCD-POP, a per capita biocultural diversity index. 56 Table 4. Highest 15 countries in IBCD-RICH and its component 61 indicators. -

Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-Country Evidence

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-country evidence Tripathi, Sabyasachi National Research University Higher School of Economics 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97474/ MPRA Paper No. 97474, posted 16 Dec 2019 14:18 UTC Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross- country evidence Dr. Sabyasachi Tripathi Postdoctoral Research Fellow Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge National Research University Higher School of Economics 20 Myasnitskaya St., 101000, Moscow, Russia Email: [email protected] Abstract: The present study assesses the impact of urbanization on the value of country-level Human Development Index (HDI), using random effect Tobit panel data estimation from 1990 to 2017. Urbanization is measured by the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, urban population growth rate, percentage of the population living in million-plus agglomeration, and the largest city of the country. Analyses are also separated by high income, upper middle income, lower middle income, and low-income countries. We find that, overall; the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, and percentage of urban population living in the million-plus agglomerations have a positive effect on the value of HDI with controlling for other important determinants of the HDI. On the other hand, urban population growth rate and percentage of the population residing in the largest cities have a negative effect on the value of HDI. Finally, we suggest that the promotion of urbanization is essential to achieving a higher level of HDI. The improvement of the percentage of urbanization is most important than other measures of urbanization. -

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam

Living Wage Report Urban Vietnam Ho Chi Minh City With focus on the Garment Industry March 2016 By: Research Center for Employment Relations (ERC) A spontaneous market for workers outside a garment factory in Ho Chi Minh City. Photo courtesy of ERC Series 1, Report 10 June 2017 Prepared for: The Global Living Wage Coalition Under the Aegis of Fairtrade International, Forest Stewardship Council, GoodWeave International, Rainforest Alliance, Social Accountability International, Sustainable Agriculture Network, and UTZ, in partnership with the ISEAL Alliance and Richard Anker and Martha Anker Living Wage Report for Urban Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam with focus on garment industry SECTION I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3 1. Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 2. Living wage estimate ............................................................................................................ 5 3. Context ................................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Ho Chi Minh City .......................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Vietnam’s garment industry ........................................................................................ 9 4. Concept and definition of a living wage ........................................................................... -

Is There Such a Thing As an Absolute Poverty Line Over Time?

Is There Such a Thing as an Absolute Poverty Line Over Time? Evidence from the United States, Britain, Canada, and Australia on the Income Elasticity of the Poverty Line by Gordon M. Fisher (An earlier version of this paper was presented October 28, 1994, at the Sixteenth Annual Research Conference of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management in Chicago, Illinois. A 9-page summary of this paper is available on the Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines Web site at http://aspe.os.dhhs.gov/poverty/papers/elassmiv.htm.) For a brief summary of the U.S. evidence in this paper, see Gordon M. Fisher, "Relative or Absolute--New Light on the Behavior of Poverty Lines Over Time," GSS/SSS Newsletter [Joint Newsletter of the Government Statistics Section and the Social Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association], Summer 1996, pp. 10-12. (This article is available on the Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines Web site at http://aspe.os.dhhs.gov/poverty/papers/relabs.htm.)) The views expressed in this paper are those of the author, and do not represent the position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. August 1995 (202)690-6143 [elastap4] CONTENTS Introduction....................................................1 Evidence from the United States--General Comment................2 Evidence from the United States--Quantitative Studies of Standard Budgets...........................................3 Evidence from the United States--Additional Quantitative Data on Standard