A Global Index of Biocultural Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unescap Working Paper Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index

WP/09/02 UNESCAP WORKING PAPER FILLING GAPS IN THE HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: FINDINGS FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC David A. Hastings Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings from Asia and the Pacific David A. Hastings Series Editor: Amarakoon Bandara Economic Affairs Officer Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific United Nations Building, Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200, Thailand Email: [email protected] WP/09/02 UNESCAP Working Paper Macroeconomic Policy and Development Division Filling Gaps in the Human Development Index: Findings for Asia and the Pacific Prepared by David A. Hastings∗ Authorized for distribution by Aynul Hasan February 2009 Abstract The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and should not necessarily be considered as reflecting the views or carrying the endorsement of the United Nations. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. This publication has been issued without formal editing. This paper reports on the geographic extension of the Human Development Index from 177 (a several-year plateau in the United Nations Development Programme's HDI) to over 230 economies, including all members and associate members of ESCAP. This increase in geographic coverage makes the HDI more useful for assessing the situations of all economies – including small economies traditionally omitted by UNDP's Human Development Reports. The components of the HDI are assessed to see which economies in the region display relatively strong performance, or may exhibit weaknesses, in those components. -

An Introduction to Biocultural Diversity

1 Biocultural Diversity To o l kit An Introduction to Biocultural Diversity Terralingua Biocultural Diversity: Earth’s Interwoven Variety he very reason our planet can be said to be T“alive” at all is because there exists here (and here alone, so far as we know) a profuse variety: of organisms, of divergent streams of human thought and behavior, and of geophysical features that provide a congenial setting for the workings of nature and culture. All three realms of difference have evolved so that they interact with and influence one another. Earth’s interwoven variety – what we call biocultural diversity - is nothing less than the pre-eminent fact of existence. David Harmon, Executive Director, The George Wright Society; Co-founder, Terralingua BIOCULTURAL DIVERSITY TOOLKIT Volume 1 - Introduction to Biocultural Diversity Copyright ©Terralingua 2014 Designed by Ortixia Dilts Edited by Luisa Maffi and Ortixia Dilts O 2 Biocultural Diversity Toolkit | BCD INTRO Table of Contents Introduction Biocultural Diversity: the True Web of Life Biocultural Diversity at a Glance The Biocultural Heritage of Mexico: a Case Study The World We Want: Ensuring Our Collective Bioculturally Resilient Future For More Information Image Credits: Cover and photo above © Cristina Mittermeier,2008; Montage left page © Cristina O Mittermeier , 2008 (photos 1, 2), © Anna Maffi, 2008 (photo 3), © Stanford Zent, 2008 (photo 4). BCD INTRO | Biocultural Diversity Toolkit 3 BIOCULTURAL DIVERSITY TOOLKIT VOL. 1. Introduction to Biocultural Diversity Introduction Luisa Maffi n the past few decades, people have become familiar Environmental degradation poses an especially Iwith the idea of biodiversity as the biological variety severe threat for these place-based societies. -

Exploring Agricultural Heritage Landscapes: a Journey Across Terra Incognita

Exploring Agricultural Heritage Landscapes: A Journey Across Terra Incognita Nora J. Mitchell and Brenda Barrett Authors’ note This article explores the values and challenges of agricultural heritage landscapes, which represent a journey across terra incognita as we venture onto less familiar terrain. Over the last several years, we have joined a group of colleagues—including other contributors to this issue—who are considering agricultural heritage landscapes in the wider context of conservation and sustainability. Discussions during the Nature–Culture Journey at the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) World Conservation Congress in Septem- ber 2016 inspired us to reflect further on what we can learn from this type of landscape, in particular, about the interconnections of nature and culture. We hope that this article will encourage further work to identify and recognize important agricultural heritage landscapes around the globe as well as in North America and will support efforts to sustain their multiple values and benefits. Introduction Conservation of agricultural heritage landscapes is receiving increased recognition and atten- tion worldwide. The term “agricultural heritage landscapes” is used here to describe produc- tive landscapes that are created and sustained by communities and have natural and cultural heritage values. These landscapes, shaped and sustained by communities, are rich in interre- lated cultural and natural heritage values and are often described as complex, dynamic bio- cultural systems. While agricultural heritage landscapes are receiving increased recognition by a variety of international and national programs, today they face many serious challenges. Several sessions in the Nature–Culture Journey1 provided an opportunity for an exchange of ideas on this type of landscape.2 This article reflects on that dialogue and, in particular, on some of the serious threats to the sustainability of these landscapes. -

The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life

Student Resource XIV The Human Development Index: Measuring the Quality of Life The ‘Human Development Index (HDI) is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development’ (UNDP). It is a measure closely related to quality of life, and is used to compare two or more countries. The United Nations developed the HDI based on three main dimensions: long and healthy life, knowledge, and a decent standard of living (see Image below). Figure 1: Indicators of HDI Source: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi In 2015, the United States ranked 8th among all countries in Human Development, ranking behind countries like Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany and Ireland (UNDP, 2015). The closer a country is to 1.0 on the HDI index, the better its standing in regards to human development. Maps of HDI ranking reveal regional patterns, such as the low HDI in Sub-Saharan Africa (Figure 2). Figure 2. The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) rankings for 2014 17 Use Student Resource XIII, Measuring Quality of Life Country Statistics to answer the following questions: 1. Categorize the countries into three groups based on their GNI PPP (US$), which relates to their income. List them here. High Income: Medium Income: Low Income: 2. Is there a relationship between income and any of the other statistics listed in the table, such as access to electricity, undernourishment, or access to physicians (or others)? Describe at least two patterns here. 3. There are several factors we can look at to measure a country's quality of life. -

The Connenction Between Global Innovation Index and Economic Well-Being Indexes

Applied Studies in Agribusiness and Commerce – APSTRACT University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Debrecen SCIENTIFIC PAPER DOI: 10.19041/APSTRACT/2019/3-4/11 THE CONNENCTION BETWEEN GLOBAL INNOVATION INDEX AND ECONOMIC WELL-BEING INDEXES Szlobodan Vukoszavlyev University of Debrecen, Faculty of Economics and Business, Hungary [email protected] Abstract: We study the connection of innovation in 126 countries by different well-being indicators and whether there are differences among geographical regions with respect to innovation index score. We approach and define innovation based on Global Innovation Index (GII). The following well-being indicators were emphasized in the research: GDP per capita measured at purchasing power parity, unemployment rate, life expectancy, crude mortality rate, human development index (HDI). Innovation index score was downloaded from the joint publication of 2018 of Cornell University, INSEAD and WIPO, HDI from the website of the UN while we obtained other well-being indicators from the database of the World Bank. Non-parametric hypothesis testing, post-hoc tests and linear regression were used in the study. We concluded that there are differences among regions/continents based on GII. It is scarcely surprising that North America is the best performer followed by Europe (with significant differences among countries). Central and South Asia scored the next places with high standard deviation. The following regions with significant backwardness include North Africa, West Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean Area, Central and South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Regions lagging behind have lower standard deviation, that is, they are more homogeneous therefore there are no significant differences among countries in the particular region. -

The Human Development Index (HDI)

Contribution to Beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Name of the indicator/method: The Human Development Index (HDI) Summary prepared by Amie Gaye: UNDP Human Development Report Office Date: August, 2011 Why an alternative measure to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) The limitation of GDP as a measure of a country’s economic performance and social progress has been a subject of considerable debate over the past two decades. Well-being is a multidimensional concept which cannot be measured by market production or GDP alone. The need to improve data and indicators to complement GDP is the focus of a number of international initiatives. The Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission1 identifies at least eight dimensions of well-being—material living standards (income, consumption and wealth), health, education, personal activities, political voice and governance, social connections and relationships, environment (sustainability) and security (economic and physical). This is consistent with the concept of human development, which focuses on opportunities and freedoms people have to choose the lives they value. While growth oriented policies may increase a nation’s total wealth, the translation into ‘functionings and freedoms’ is not automatic. Inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth, unemployment, and disparities in access to public goods and services such as health and education; are all important aspects of well-being assessment. What is the Human Development Index (HDI)? The HDI serves as a frame of reference for both social and economic development. It is a summary measure for monitoring long-term progress in a country’s average level of human development in three basic dimensions: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. -

Biocultural Diversity and Sustainability

18-Pretty-Ch18 6/22/07 3:18 PM Page 267 18 Biocultural Diversity and Sustainability Luisa Maffi with the environment and thus of the relationships INTRODUCTION between the state of the environment, the threats or pressures on it, and the response options to Conventional approaches to environmental con- counter or alleviate the threats. Three will be men- servation have tended to consider the role of tioned here in particular. humans only or mostly in terms of the threats that In the natural sciences, the field of ecosystem the intensification of human extractive and trans- health (Rapport, 1998, 2007) embraces a formative activities poses for the environment. “humans-in-environment” approach which, while From this perspective, finding solutions to envi- acknowledging that the global commons are ronmental problems largely means seeking to put severely imperiled by human action, takes as its a halt to those activities by “taking human hands main goal to address Aldo Leopold’s challenging off ” what is seen as the last remaining pristine question: how can we humanly occupy the Earth environments on the planet (Terborgh, 1999). without rendering it dysfunctional? In the social Underlying this perspective is a philosophical sciences, the field of biocultural diversity (Maffi, view that depicts humans as external to, and sepa- 2001a, 2005) – drawing from anthropological, rate from, nature, and interacting with it mostly in ethnobiological, and ethnoecological insights an effort to establish dominion over it (Eldredge, about the relationships of human language, 1995). Complementarily, nature is seen as sepa- knowledge, and practices with the environment – rate from humans and as existing in a primordial, takes as its fundamental assumption the existence “virgin” state unless and until they are encroached of an “inextricable link” between biological and upon by humans. -

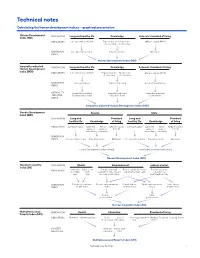

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

Exploring Biocultural Diversity Through Art

Copyright © 2017 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Polfus, J. L., D. Simmons, M. Neyelle, W. Bayha, F. Andrew, L. Andrew, B. G. Merkle, K. Rice, and M. Manseau. 2017. Creative convergence: exploring biocultural diversity through art. Ecology and Society 22(2):4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08711-220204 Research, part of a Special Feature on Reconciling Art and Science for Sustainability Creative convergence: exploring biocultural diversity through art Jean L. Polfus 1, Deborah Simmons 2,3, Michael Neyelle 2,4, Walter Bayha 5, Frederick Andrew 2, Leon Andrew 2, Bethann G. Merkle 6, Keren Rice 7 and Micheline Manseau 1,8 ABSTRACT. Interdisciplinary approaches are necessary for exploring the complex research questions that stem from interdependence in social-ecological systems. For example, the concept of biocultural diversity, which highlights the interactions between human diversity and the diversity of biological systems, bridges multiple knowledge systems and disciplines and can reveal historical, existing, and emergent patterns of variation that are essential to ecosystem dynamics. Identifying biocultural diversity requires a flexible, creative, and collaborative approach to research. We demonstrate how visual art can be used in combination with scientific and social science methods to examine the biocultural landscape of the Sahtú region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Specifically, we focus on the intersection of Dene cultural diversity and caribou (Rangifer tarandus) intraspecific variation. We developed original illustrations, diagrams, and other visual aids to increase the effectiveness of communication, improve the organization of research results, and promote intellectual creativity. For example, we used scientific visualization and drawings to explain complex genetic data and clarify research priorities. -

Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-Country Evidence

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross-country evidence Tripathi, Sabyasachi National Research University Higher School of Economics 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/97474/ MPRA Paper No. 97474, posted 16 Dec 2019 14:18 UTC Urbanization and Human Development Index: Cross- country evidence Dr. Sabyasachi Tripathi Postdoctoral Research Fellow Institute for Statistical Studies and Economics of Knowledge National Research University Higher School of Economics 20 Myasnitskaya St., 101000, Moscow, Russia Email: [email protected] Abstract: The present study assesses the impact of urbanization on the value of country-level Human Development Index (HDI), using random effect Tobit panel data estimation from 1990 to 2017. Urbanization is measured by the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, urban population growth rate, percentage of the population living in million-plus agglomeration, and the largest city of the country. Analyses are also separated by high income, upper middle income, lower middle income, and low-income countries. We find that, overall; the total urban population, percentage of the urban population, and percentage of urban population living in the million-plus agglomerations have a positive effect on the value of HDI with controlling for other important determinants of the HDI. On the other hand, urban population growth rate and percentage of the population residing in the largest cities have a negative effect on the value of HDI. Finally, we suggest that the promotion of urbanization is essential to achieving a higher level of HDI. The improvement of the percentage of urbanization is most important than other measures of urbanization. -

Empowering Indigenous Agency Through Community-Driven Collaborative Management to Achieve Effective Conservation: Hawai‘I As an Example

SPECIAL ISSUE CSIRO PUBLISHING Pacific Conservation Biology Perspective https://doi.org/10.1071/PC20009 Empowering Indigenous agency through community-driven collaborative management to achieve effective conservation: Hawai‘i as an example Kawika B. Winter A,B,C,D,N, Mehana Blaich VaughanB,E,F, Natalie KurashimaD,G, Christian GiardinaD,H, Kalani Quiocho B,I, Kevin ChangD,J, Malia AkutagawaE,K,L, Kamanamaikalani BeamerE,K and Fikret BerkesM AHawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Ka¯ne‘ohe, HI, USA. BNatural Resources and Environmental Management, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Honolulu, HI, USA. CNational Tropical Botanical Garden, Kala¯heo, HI, USA. DHawai‘i Conservation Alliance, Honolulu, HI, USA. EHui ‘Aina¯ Momona Program, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Honolulu, HI, USA. FUniversity of Hawai‘i Sea Grant College Program, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Honolulu, HI, USA. GNatural and Cultural Ecosystems, Kamehameha Schools, Kailua-Kona, HI, USA. HInstitute of Pacific Island Forestry, US Forest Service, Hilo, HI, USA. IPapaha¯naumokua¯kea Marine National Monument, Honolulu, HI, USA. JKua‘a¯ina Ulu Auamo, Ka¯ne‘ohe, HI, USA. KHawai‘inuia¯kea School of Hawaiian Knowledge – Kamakakuokalani% Center for Hawaiian Studies, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Honolulu, HI, USA. LWilliam S. Richardson School of Law – Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law, University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa, Honolulu, HI, USA. MNatural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. NCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) around the world are increasingly asserting ‘Indigenous agency’ to engage with government institutions and other partners to collaboratively steward ancestral Places. -

Exploring Biocultural Approaches to Education Terralingua Langscape Volume 3, Issue 1 Exploring Biocultural Approaches to Education

VOLUME 3, ISSUE 1 | SUMMER 2014 Langscape WITH GUEST EDITOR | YVONNE VIZINA Exploring Biocultural Approaches to Education Terralingua Langscape Volume 3, issue 1 Exploring Biocultural Approaches to Education here was a time with no schools—a time when nature and community were our teachers, and they taught us everything we needed to know Tin order to live respectfully and care for one another and for the land. We Langscape is an extension of the voice of Terralingua. It have come a long way from that. With the rise and spread of formal learning institutions, over time our concepts of “knowledge” and “education” have supports our mission by educating the minds and hearts become less and less associated with everyday-life, hands-on, holistic about the importance and value of biocultural diversity. experience and more and more with academic study and research—the body of systematic thought and inquiry that we call “science”. We aim to promote a paradigm shift by illustrating Science and its countless applications have permeated all realms of biocultural diversity through scientific and traditional human life. But, enclosed inside the walls of our learning institutions, knowledge, within an elegant sensory context of articles, compartmentalized within the silos of different, specialized disciplines, we have become insular and disconnected. We have lost sight of ourselves as stories and art. a part of—not separate from and dominant over—the natural world, and as inextricably linked with all other peoples and all other species on earth in a global web of interdependence: the web of life in nature and culture Langscape is a Terralingua publication that is now known as “biocultural diversity”.