The Eleventh Season: from Bach Jul Y 18–August 10, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

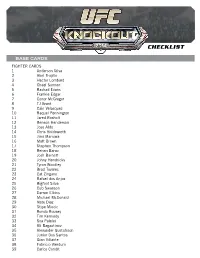

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

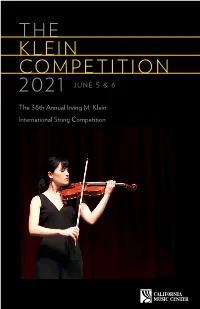

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE to BROOKLYN Judith E

L(30 '11 II. BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel, Ame Vennema, Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Harry W. Albright, Jr., Henry Bing, Jr., Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Judah Gribetz, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti; Hon. Henry Geldzahler, Member ex-officio. A STAR SPANGLED OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer SALUTE TO BROOKLYN Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and General Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development IN HONOR OF THE 100th ANNIVERSARY Micheal House Vice President for Marketing and Promotion ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF OF THE Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk BROOKLYN BRIDGE FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Tuesday, November 30, 1982 Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION Marketing Nancy Rossell Assistant to Vice President Susan Levy Director of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro Development Officer Philip Bither Development Officer Sharon Lea Lee Office Manager Aaron Frazier Administrative Assistant MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Jack L. -

Jeffrey Kahane

JEFFREY KAHANE Equally at home at the piano or on the podium, Jeffrey Kahane is recognized around the world for his mastery of a diverse repertoire ranging from Bach and Mozart to the music of our time. Kahane has appeared as soloist with major orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Chicago and San Francisco Symphonies, and is also a popular artist at all of the major US summer festivals, including Aspen, Blossom, Caramoor, Mostly Mozart, and Ravinia. In August 2016 he was appointed Music Director of the Sarasota Music Festival, which offers master classes and chamber music coaching by a distinguished international faculty, and features chamber music performances and orchestral concerts performed by highly advanced students and young professionals, as well as faculty members. Since making his Carnegie Hall debut in 1983, he has given recitals in many of the nation’s major music centers including New York, Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Atlanta. A highly respected chamber musician, Kahane collaborates with many of today’s most important chamber ensembles and was the Artistic Director of the Green Music Center Chamberfest during the summers of 2015 and 2016. Kahane made his conducting debut at the Oregon Bach Festival in 1988. Since then, he has guest conducted many of the major US orchestras including the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics; Philadelphia and Cleveland Orchestras; Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra; and the Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Baltimore, Indianapolis, and New World Symphonies. In May 2017 Kahane completed his 20th and final season as Music Director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. -

Universal Sales & Service Ltd

- ---' ','" ,- {C'.: ',,,_/. ,",:,.- _ .' c. " • .-~- - '-'~" . ".- I _t'r: ., ' Page Five . r-: 7""~~: --_._-----,------ --_ .. _.- "," " ','; ~ THE. JEWISH POST - ~ .. ~' Thur~day, July 5, 1951 .. Thursday, July 5, 1951 / highlighted hy the presentation of \ ports of activities. during the past c~rtificate awards and gifts and re- year.. (See page 6.) .- THE JEWISH POST Hold Annivesary Windup: Lorne Pearlman,. so'n of Mr. and - p~ge Four Consulate General at 1260 Univer Dr. C. D. Rusen Heads Mrs. J. Pearlman, has returned from the Israel Ministry Education, ~eabstone of sity Street, Montreal, so that tbe Shaarey Zedek Scene of Levy.Myers Wedding Alpha Omega Dental portland, Ore., to visit here for the thei Consulate General of Israel in Twin Chapters' Windup necessary fonns can be forwarde-d 1t summer. He is attending the Uni Canada requests all Israeli stu The Shaarey Zedek Fraternity Wnbeiling versity of Oregon Dental College. dents to contact the office of the to them. SOCIAL AND synagogue was the col .. At a recent meeting of the Alpha orful setting of the after Omega Dental fraternity, Dr. Chas. The Family 91 the Late Jsaac Y urman Passes , . "YOU'LL ENJOY SHOPPING .ATGOLDEN'S" noon wedding of Audrey Rusen was elected president for the Entirety Air Conditioned jar Your Comfort PERSONAL Roslyn, only daughter of coming year. Other officers elected Suddenly, Aged 68 MRS. ROSE Mrs. G. Myers, and ISAACOVITCH Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Robinson, are: Isaac Yunnan, 329 Burrows ave I. Sheldon, oniy son of' Immediate past president, Dr. H. 334 Wellington crescent, announce nue, passed· away Sunday night, requests all their relatives and Mrs. -

Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Guest Artist Cello Concert Bryan Hayslett Tuesday, October 28, 2014 • 7:30 p.m. Belhaven University Center for the Arts • Concert Hall There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performer. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM Please hold applause until intermission. Cello Suite No. 6 in D Major, BWV 1012 Johann Sebastian Bach • 1685 - 1750 I. Prelude Unlocked, 1. Make Me a Garment Judith Weir • b. 1954 Unlocked, 2. No Justice A Portrait in Greys Marissa Deitz Wall • b. 1990 Suite No. 6, 2. Allemande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 3. Courante Age of the Deceased (Six Months in Chicago) Drew Baker • b. 1978 INTERMISSION Suite No. 6, 4. Sarabande J.S. Bach Suite No. 6, 5. Gavotte A Portrait in Greys Keith Kusterer • b. 1981 Unlocked, 5. Trouble, trouble Judith Weir Suite No. 6, 6. Gigue J.S. Bach A Portrait in Greys by William Carlos Williams Will it never be possible to separate you from your greyness? Must you be always sinking backward into your grey-brown landscapes— And trees always in the distance, always against a grey sky? Must I be always moving counter to you? Is there no place where we can be at peace together and the motion of our drawing apart be altogether taken up? I see myself standing upon your shoulders touching a grey, broken sky— but you, weighted down with me, yet gripping my ankles,—move laboriously on, where it is level and undisturbed by colors. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996

BOSTON > V SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ft SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E O N The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLumlc Composition Fidelity Just as a Beethoven score is at its best when performed by a world- Pergonal class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Triittt a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. That's why Fidelity now offers a % managed trust or personalized estment management account or your portfolio of $400,000 or more/ For more information, visit Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Trust Services at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments' SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes Chairman-elect William F. -

Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-25-2006 Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury Debra Moree Elizabeth Simkin Jennifer Hayghe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Waterbury, Susan; Moree, Debra; Simkin, Elizabeth; and Hayghe, Jennifer, "Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III" (2006). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5058. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5058 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC FACULTY RECITAL MOZART/SHOSTAKOVICH III An evening of chamber music celebrating the 250th birth anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) and the 100th birth anniversary of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Susan Waterbury, violin Debra Moree, viola Elizabeth Simkin, cello Jennifer Hayghe, piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Monday, September 25, 2006 7:00 p.m. ITHACA I PROGRAM Piano Sonata No. 18 in D Major, Wolfgang Amadeus :Mozart K576 (1789) (1756-1791) Allegro Adagio Allegretto Sonata for Viola & Piano, Op. 147 (1975) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Moderato Allegretto Adagio INTERMISSION Trio for Violin, Cello & Piano, Dmitri Shostakovich No. 2 in e minor, Op. 67 (1944) Andante Allegro non troppo Largo Allegretto Program Notes Mozart and Shostakovitch III The pairing of Mozart and Shostakovich, born 150 years apart, is more natural than e might initially suspect. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756- 5 cember 1791), the seventh and last child born to Leopold Mozart and his wife Maria Anna, is the most famous musical prodigy in history. -

A Healing Return to the Stage for the Canton Symphony Orchestra by Tom Wachunas

A Healing Return to the Stage for the Canton Symphony Orchestra by Tom Wachunas Reasons to be cheerful: they’re back! The May 23 concert by the Canton Symphony Orchestra marked the first time in more than a year that the ensemble has performed live at Umstattd Performing Arts Hall. This occasion was certainly an important step on the road back to cultural “normalcy” as we recover from the dreadful pandemic shutdown. For a May 21 article by Ed Balint in The Repository (Canton’s daily newspaper), CSO president and CEO Michelle Charles said of the concert, “That’s what we do, that’s what we love and that’s why we exist, to perform music live. You do take for granted how readily available (classical music) is until it’s not. So I think it’s going to be very emotional.” Noting the special significance of the concert to Gerhardt Zimmermann, CSO music director and conductor since 1980, she added, “It’s been so long, and Canton has held a special place in his heart for many, many years. I think it’s going to be more emotional for him than anyone.” The emotional factor becomes even more resonant when considering Zimmermann’s own battle with coronavirus which led to weeks of hospitalization and rehabilitation in 2020. He’s still not at optimal strength, and consequently conducted the program while seated on a raised platform. This short concert (with no intermission) was an altogether unique sensory experience, and not a CSO business-as-usual affair. Zimmermann chose just two works to be on the program: Mendelssohn’s String Octet, and Mozart’s Symphony No. -

List of Works 2003

Christian Mason Full Works List 2003 – Present Date Piece Premiere Premiere Performer(s) / Subsequent Performances Date/Place Artist(s) ORCHESTRA In Preparation From Space the Earth is Blue… TBC Nathalie Forget, Ensemble Concerto for ondes martenot, soloist ensemble (8 l’Itinéraire, Orchestre players), chamber orchestra, female voice choice d’Auvergne and choir In Preparation New Commission 2021 - Lucerne Festival Academy c.20 mins. Donaueschingen Alumni Orchestra Symphony Orchestra, ondes martenot (tbc) Festival, Donaueschingen, Germany 2020 However long a time may pass…All things must 2020, June 4th, Konzerthausorchester Berlin 2020, June 5th – 6th, Berlin Konzerthaus, Germany yet meet again… Berlin Konzerthaus, (cond: Christoph Eschenbach) 21 mins. Berlin, Germany 2020, June 7th, Dortmund Konzerthaus, Germany Symphony Orchestra 2020, June 8th, Hamburg Elbphilharmonie, Germany 2020, June 20th, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Festival, Germany (tbc) 2019 Eternity in an hour 2019, April 27th, Wiener Philharmoniker (cond: 2019, April 28th, Musikverein, Golden Hall, Vienna, 15 mins. Musikverein, Golden Christian Thielemann) Austria Symphony Orchestra Hall, Vienna, Austria 2019, May 2nd, Berlin Dom, Berlin, Germany 2019 Eternal Return 2019, January 26th - hr-sinfonieorchester (cond: 7 mins. Breitkopf Festival Michal Nesterowicz) Symphony Orchestra Jubilee concert, Kurhaus Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, Germany 2018 Man Made 2018, May 24th, Royal Philharmonia, Anu Komsi 18 mins. Festival Hall (Music of (soprano) (cond: Gergely Soprano and Ensemble Today series),