Making Myanmar-Colonial Burma and Popular Western Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karen-Burmese Refugees

Karen-Burmese Refugees An orientation for health workers and volunteers Developed by Christine Dziedzic, Student Project Officer Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health Background Information • The Karen-Burmese live in mountainous jungle regions of Myanmar (southern and eastern), and Thailand • Myanmar is located in South- East Asia – Formally known as Burma – Developing and largely rural – Bordered by China, Tibet, Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh and India Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Myanmar - Background InformationWorld Health Organisation (2006) • Population: 50 519 000 • Life expectancy at birth: – 61 years • Infant mortality rate – Per 1000 live births: 106 – 4.7 / 1000 in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006) • Language: Burmese – Indigenous peoples have their own languages Flag of Myanmar – Over 126 dialects Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 History of Myanmar • 1886: Became a province of British India • 1948: Gained independence • 1962: Military dictatorship took power – Large outflow of refugees • 1988: Martial law declared – Increased refugee numbers • State of civil war for much of the past 50 years Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Ethnic Groups • Major ethnic group: Burmese • Largest indigenous population: Karen • Other indigenous races include: – Shans – Chins – Mon – Rakhine – Katchin • Ethnic tension -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

Roy Thomas ’Merry Mar vel Comics Fan zine No. 50 July 2005 $ In5th.e9U5SA Sub-Mariner, Thing, Thor, & Vision TM & ©2005 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Conan TM & ©2005 Conan Properties, Inc.; Red Sonja TM & ©2005 Red Sonja Properties, Inc.; Caricature ©2005 Estate of Alfredo Alcala Vol. 3, No. 50 / July 2005 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Roy Thomas Associate Editors Shamelessly Celebrates Bill Schelly 50 Issues of A/E , Vol. 3— Jim Amash & 40 Years Since Design & Layout Christopher Day Modeling With Millie #44! Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Contents Mike Friedrich Production Assistant Writer/Editorial: Make Mine Marvel! . 2 Eric Nolen-Weathington “Roy The Boy” In The Marvel Age Of Comics . 4 Cover Artists Jim Amash interviews Roy Thomas about being Stan Lee’s “left-hand man” Alfredo Alcala, John Buscema, in the 1960s & early ’70s. & Jack Kirby Jerry Ordway DC Comics 196 5––And The Rest Of Roy’s Cover Colorist Color-Splashed Career . Flip Us! Alfredo Alcala (portrait), Tom Ziuko About Our Cover: A kaleidoscopically collaborative combination of And Special Thanks to: three great comic artists Roy worked with and admired in the 1960s and Alfredo Alcala, Jr. Allen Logan ’70s: Alfredo Alcala , John Buscema , and Jack Kirby . The painted Christian Voltan Linda Long caricature by Alfredo was given to him as a birthday gift in 1981 and Alcala Don Mangus showed Rascally Roy as Conan, the Marvel-licensed hero on which the Estelita Alcala Sam Maronie Heidi Amash Mike Mikulovsky two had labored together until 1980, when R.T. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Burma – Myanmar

BURMA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Jerome Holloway 1947-1949 Vice Consul, Rangoon Edwin Webb Martin 1950-1051 Consular Officer, Rangoon Joseph A. Mendenhall 1955-1957 Economic Officer, Office of Southeast Asian Affairs, Washington DC William C. Hamilton 1957-1959 Political Officer, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel, Jr. 1957-1961 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Kenneth A. Guenther 1958-1959 Rangoon University, Rangoon Cliff Forster 1958-1960 Information Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton Smith 1958-1963 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton I. Abramowitz 1959 Temporary Duty, Economic Officer, Rangoon Jack Shellenberger 1959-1962 Branch Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Moulmein John R. O’Brien 1960-1962 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Robert Mark Ward 1961 Assistant Desk Officer, USAID, Washington, DC George M. Barbis 1961-1963 Analyst for Thailand and Burma, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington DC Robert S. Steven 1962-1964 Economic Officer, Rangoon Ralph J. Katrosh 1962-1965 Political Officer, Rangoon Ruth McLendon 1962-1966 Political/Consular Officer, Rangoon Henry Byroade 1963-1969 Ambassador, Burma 1 John A. Lacey 1965-1966 Burma-Cambodia Desk Officer, Washington DC Cliff Southard 1966-1969 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Edward C. Ingraham 1967-1970 Political Counselor, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel Jr. 1968-1971 Ambassador, Burma Robert J. Martens 1969-1970 Political – Economic Officer, Rangoon G. Eugene Martin 1969-1971 Consular Officer, Rangoon 1971-1973 Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Edwin Webb Martin 1971-1973 Ambassador, Burma John A. Lacey 1972-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Rangoon James A. Klemstine 1973-1976 Thailand-Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Frank P. Coward 1973-1978 Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Richard M. -

Merit-Making and Monuments: an Investigation Into the Role of Religious Monuments and Settlement Patterning Surrounding the Classical Capital of Bagan, Myanmar

MERIT-MAKING AND MONUMENTS: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE ROLE OF RELIGIOUS MONUMENTS AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNING SURROUNDING THE CLASSICAL CAPITAL OF BAGAN, MYANMAR A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfill of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada ã Copyright by Ellie Tamura 2019 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2020 ABSTRACT Merit-Making and Monuments: An Investigation into the Role of Religious Monuments and Settlement Patterning Surrounding the Classical Capital of Bagan, Myanmar Ellie Tamura Bagan, Myanmar’s capital during the country’s Classical period (c. 800-1400 CE), and its surrounding landscape was once home to at least four thousand monuments. These monuments were the result of the Buddhist pursuit of merit-making, the idea that individuals could increase their socio-spiritual status by performing pious acts for the Sangha (Buddhist Order). Amongst the most meritous act was the construction of a religious monument. Using the iconographic record and historical literature, alongside entanglement theory, this thesis explores how the movement of labour, capital, and resources for the construction of these monuments influenced the settlement patterns of Bagan’s broader cityscape. The findings suggest that these monuments bound settlements, their inhabitants, and the Crown, in a variety of enabling and constraining relationships. This thesis has created the foundations for understanding the settlements of Bagan and serves as a useful platform to perform comparative studies once archaeological data for settlement patterning becomes available. Keywords: Southeast Asia, Settlement Patterns, Bagan, Entanglement, Religious Monuments, Buddhism, Archaeology ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For the past three years, I have been incredibly fortunate in having the opportunity to do what I love, in one of the most wonderful countries, none of which would have been possible without the support of an amazing group of people. -

Fall 2020Fall 2020

HarE JoHn HarE Students dressed is a freelance illustrator and in deep-sea diving graphic designer who works on Field Trip suits travel to the a range of projects. He lives in ocean deep in a yellow Gladstone, Missouri, with his submarine school bus. wife and two children. When they get there, they are introduced to creatures like T PRAISE FOR Field Trip to the Moon o luminescent squids and giant T he isopods, and discover an old ocean deep shipwreck. But when it’s time to return to the submarine bus, one student lingers to take a photo of a treasure chest and A Junior Library Guild Selection falls into a deep ravine. Luckily, A School Library Journal Best Book of the Year the child is entertained by a The Horn Book Fanfare List mysterious sea creature until ★ “Hare’s picture book debut is a winner . being retrieved by the teacher. A beautifully done wordless story about BOOKS FERGUSON MARGARET In his follow-up to Field Trip to a field trip to the moon with a sweet and funny alien encounter.”—School Library the Moon, John Hare’s rich, Journal, starred review atmospheric art in this wordless “[An] auspicious debut presents a world picture book invites children where a yellow crayon box shines Holiday House to imagine themselves in the like a beacon.”—Booklist story—a story full of surprises. MARGARET FERGUSON BOOKS BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE US $17.99$17.99 / CAN / CAN $23.99 $23.99 ISBN: 978-0-8234-4630-8 Holiday House Publishing, Inc. 5 1 7 9 9 HolidayHouse.com EAN Fall 2020 Printed in China 9 780823 446308 0408 Reinforced Illustration © 2020 by John Hare from Field Trip to the Ocean Deep HOLIDAY HOUSE Apples Gail Gibbons Summary Find out where your favorite crunchy, refreshing fruit comes from in this snack-sized book. -

Back on the Tourist Trail After Almost 20 Years, Yangon

FLY MYANMAR ORNING COMES early here. By 5am, the streets are full of vendors, all getting ready to cook breakfast for the city’s hungry workforce. Chai is the country’s GOLDEN morning drink of choice and is served in small glass cups, steaming hot and very sweet. !e little wooden chairs outside the vendors’ stalls are soon filled, as men and sarong-clad women stop for a hot drink before getting on with their day. MOMENTS It is a familiar scene in many cities across Asia, but this is not one of the continent’s more well-known visi- Yangon tor locales, such as Bangkok, Hanoi or even Beijing. Rangoon !is is Yangon, formerly known as Rangoon and, not Myanmar TEXT/ CORI HOWARD so long ago, the capital of Myanmar, a country still Burma more familiar to many as Burma. 2006 Supplanted by Naypyidaw as the country’s capital in Back on the tourist trail after almost 2006, Yangon remains Myanmar’s busiest and most 20 populous city. It is getting used to welcoming visitors 20 years, Yangon offers a whole new again, with various political wranglings, both domesti- generation a wonderful taste of cally and internationally, keeping it off the tourist trail for almost 20 years. Myanmar’s culture, cuisine and history !e drive from the gleaming, new international air- port into Yangon takes you through dusty, bustling roads where street hawkers sell piles of old shoes and 20 women walk by balancing heavily laden baskets of fruit on their heads. Barefoot monks in saffron robes shade their shaved heads from the hot sun with rattan fans, while bare-chested men in sarongs pedal rickshaws alongside diesel-belching buses and the occasional, somewhat incongruous, brand-new SUV. -

Tarzan in the Early-20Th Century French Fantasy Landscape By

Wesleyan University The Honors College The Missing Link: Tarzan in the Early-20th Century French Fantasy Landscape by Medha Swaminathan Class of 2019 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in French Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Embracing the Invented in the “Benevolent” Colonial ................................................ 9 Imagining “Africa” ..................................................................................................... 19 Le Tour du Monde en Un Jour: Tarzan and the 1930s Paris Colonial Exhibitions .... 36 “Civilization” vs. “Civilized” vs. “Savage” ................................................................ 49 Homme Idéal or Missing Link? Fetish, Fascination, and Fear in French Eugenics ... 57 Sex, Youth, Beauty, Valor, and the Légionnaire ........................................................ 70 Saturnin Farandoul: Tarzan’s French Foil? ................................................................ 81 “Comment dit-on sites de rêve en anglais ?” .............................................................. 96 References ................................................................................................................. 100 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without an incredible amount -

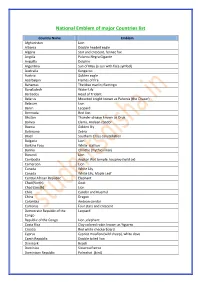

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

Animal Agency, Undead Capital and Imperial Science in British Burma

BJHS: Themes 2: 169–189, 2017. © British Society for the History of Science 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/bjt.2017.6 First published online 24 April 2017 Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma JONATHAN SAHA* Abstract. Elephants were vital agents of empire. In British Burma their unique abilities made them essential workers in the colony’s booming teak industry. Their labour was integral to the commercial exploitation of the country’s vast forests. They helped to fell the trees, transport the logs and load the timber onto ships. As a result of their utility, capturing and caring for them was of utmost importance to timber firms. Elephants became a peculiar form of capital that required particular expertise. To address this need for knowledge, imperial researchers deepened their scientific understanding of the Asian elephant by studying working elephants in Burma’s jungle camps and timber yards. The resulting knowledge was contingent upon the conscripted and constrained agency of working elephants, and was conditioned by the asymmetrical power relationships of colonial rule. Animal agency Writing in the interwar years about his life working in the timber industry of colonial Burma during the late nineteenth century, John Nisbet recalled how Mounggyi, having been one of the best-natured and tamest elephants he had known, became unmanageable due to a bout of musth. -

Buddhist Art of Myanmar Press Release FINAL.Pdf

News Communications Department Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9313; [email protected] E-mail [email protected] ASIA SOCIETY MUSEUM TO PRESENT FIRST EXHIBITION IN THE WEST FOCUSED ON LOANS FROM COLLECTIONS IN MYANMAR Buddhist Art of Myanmar on view in New York February 10 through May 10, 2015 Asia Society Museum presents a landmark exhibition of spectacular works of art from collections in Myanmar and the United States. Buddhist Art of Myanmar comprises approximately 70 works from the fifth through the early twentieth century and includes stone, bronze, and lacquered wood sculptures as well as textiles, paintings, and ritual implements. The majority of works in the exhibition on loan from Myanmar have never been seen in the West. On view in New York from February 10 through May 10, 2015, the exhibition showcases Buddhist objects created for temples, monasteries, and personal devotion, presented in their historical and ritual contexts. Exhibition artworks highlight the long and continuous presence of Buddhism in Myanmar since Plaque with image of seated Buddha. Pagan period, the first millennium, as well as the unique combination 11th -13th century . Gilded metal with polychrome. of style, technique, and religious deities that appeared 7 x 6.14 x 0.25 in . (17.8 x15.9 x 0.6 cm). Bagan Archaeological Museum. Photo: Sean Dungan. in the arts of Buddhist Myanmar. Buddhist Art of Myanmar includes loans from the National Museums in Yangon and Nay Pyi T aw, the Bagan Archaeological Museum, Sri Ksetra Archaeological Museum, and the Kaba Aye Buddhist Art Museum, as well as works from public and private collections in the United States. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................