'It Was Hard to Die Frae Hame'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symond Street Cemetery: Hobson Walk

Symonds Street Cemetery Hobson Walk Key D St Martins Lane Walkway 15 Trail guide for the Anglican andKarangahape General/Wesleyan Road sections Informal route Symonds Street14 Hobson Walk 1 Site in this trail guide 16 E B Cemetery entrance Known grave C 17 Grafton Cycleway/ walkway B 1 18 13 2 12 Upper Queen Street Grafton Bridge 3 4 Panoramic view looking along Grafton Gully from Symonds Street Cemetery, c1869. Sir George Grey Special Collections, 5 Auckland Libraries, 4-319. F The Hobson Walk - explore Symonds Street 6 11 our oldest public cemetery This trail guide will introduce you to some interesting parts of the Anglican and General/Wesleyan sections of the Symonds Street Cemetery. The Anglican Cemetery 7 was the first to be established here, so contains the oldest graves, and those of many prominent people. To do the Hobson Walk will take about 45 minutes. 10 Follow the blue markers. So Some of this trail does notu followth formed paths. Make ern 9 m sure you wear appropriate footwear,M especially in winter, a o e to r and please do not walk across the graves. rw t a S y 8 u r u From this trail, you can link to two more walks in r a p the lower section of the cemetery and gully - Bishop ai Selwyn’s Walk and the Waiparuru Nature Trail. W You can access more information on our mobile app (see back page). 25-9-19 S o u th e Alex Evans St rn M Symonds Street o to rw a y Their influence meant the Anglicans were given what was considered to be the best location in this multi- denominational cemetery site, with the most commanding views of the Waitematā Harbour and Rangitoto Island and beyond. -

Fifty Years of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand Page 1

Fifty Years of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand Page 1 Fifty Years of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand FIFTY YEARS Of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand. CONTENTS. PREFACE PART I.—INTRODUCTION. CHAPTER I.—NEW ZEALAND. 1. DISCOVERY 2. PIONEERS 3. THE MAORIS 4. MISSION WORK 5. SETTLEMENT CHAPTER II.—PRIMITIVE METHODISM. 1. ORIGIN 2. GROWTH AND DIFFICULTIES 3. CHURCH POLITY AND DOCTRINES PART II.—PRIMITIVE METHODISM IN NEW ZEALAND. CHAPTER I.—TARANAKI 1. NEW PLYMOUTH STATION 2. STRATFORD MISSION CHAPTER II.—WELLINGTON 1. WELLINGTON STATION 2. MANAWATU STATION 3. FOXTON STATION 4. HALCOMBE STATION 5. HUNTERVILLE MISSION CHAPTER III—AUCKLAND 1. AUCKLAND STATION 2. AUCKLAND II. STATION 3. THAMES STATION CHAPTER IV.—CANTERBURY 1. CHRISTCHURCH STATION Page 2 Fifty Years of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand 2. TIMARU STATION 3. ASHBURTON STATION 4. GREENDALE STATION 5. GERALDINE STATION 6. WAIMATE AND OAMARU MISSION CHAPTER V.—OTAGO 1. DUNEDIN STATION 2. INVERCARGILL STATION 3. SOUTH INVERCARGILL MISSION 4. BLUFF BRANCH CHAPTER VI—NELSON 1. WESTPORT AND DENNISTON MISSION CHAPTER VII.—GENERAL EPITOME. 1. CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY 2. SUMMARY ILLUSTRATIONS. REV. ROBERT WARD MAORIDOM GROUP OF MINISTERS AND LAYMEN DEVON STREET, NEW PLYMOUTH MOUNT EGMONT WELLINGTON GROUP OF MINISTERS QUEEN STREET, AUCKLAND FRANKLIN ROAD CHURCH, AUCKLAND CHRISTCHURCH CAMBRIDGE TERRACE CHURCH, CHRISTCHURCH GROUP OF LAYMEN DUNEDIN DON STREET CHURCH, INVERCARGILL Page 3 Fifty Years of Primitive Methodism in New Zealand PREFACE This book owes its existence to a desire to perpetuate the memory of those pioneer ministers and laymen who founded the Primitive Methodist Connexion in different parts of this Colony. The Conference of 1893 showed its approval of the desire by authorising the publication of a Memorial Volume in connection with our Jubilee Celebrations. -

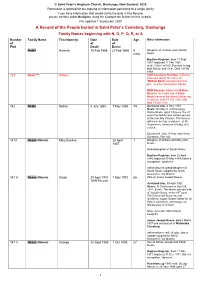

05 Family Names Beginning with N

© Saint Peter’s Anglican Church, Onehunga, New Zealand: 2020 Permission is granted for the copying of information pertaining to a single family If you have information that would clarify the data in this Record, please contact John McAlpine using the Contact Us Button on this website. File updated 1 September 2020 A Record of the People buried in Saint Peter’s Cemetery, Onehunga Family Names beginning with N, O, P, Q, R, or S Number Family Name First Name(s) Date Date Age Other Information of of of Plot Death Burial Nadin Hannah 18 Feb 1868 21 Feb 1868 5 Daughter of Thomas and Hannah mths Nadin. Baptism Register: born 13 Sept 1867; baptised 11 Feb 1868 at the ‘Clinic’ of A.G. Purchas, being both Doctor and Vicar. Died 18 Feb 1868. 267 Nash *** William 1898 Cemetery Plot Map: indicates that a person by the name of ‘William Nash’ was buried in this plot; no other information offered. BDM Records: Might this William Nash be the infant son of Ellen Nash (name of the infant’s father not recorded), born 17 Oct 1882, and died 19 Oct 1882. 142 Neate Selina 5 July 1880 7 May 1880 74 Auckland Star, 6 May 1880: Neate: On May 5, at Onehunga, Selina Neate; aged 74 years. For 27 years the faithful and valued servant of the late Mrs Churton. The funeral will leave her late residence, at Mr Oxenham’s, tomorrow (Friday) at 3 o’clock. Buried with John, Selina, and Henry Oxenham. Plot 142 141A Neave (Neeve) Mary Eveline 26 April 1 Daughter of William and Mary Ann 1887 Neave. -

Appendix 9.1 Schedule of Significant Historic Heritage Places 18 September 2015 Council's Proposed Changes Are Shown in Striket

Appendix 9.1 Schedule of Significant Historic Heritage Places 18 September 2015 Council's proposed changes are shown in strikethrough and underline Black text changes record amendments proposed in first mediation session Green text changes record amendments proposed and agreed to in mediation Red text changes record amendments proposed in rebuttal evidence Blue text changes record amendments proposed post hearing (e.g. right of reply) Yellow highlighted text changes record amendments that are considered to be outside the scope of submissions. Grey highlight text changes record consequential amendments. [all provisions in this appendix are: rcp/dp] Heritage values The sSchedule of Significant hHistoric hHeritage pPlaces identifies historic heritage places in Auckland which have significant historic heritage value. The heritage value evaluation criteria against which historic heritage places are evaluated are set out in the RPS - Historic Heritage. They are The evaluation criteria that are relevant to each scheduled historic heritage place are identified in the schedule using the following letters: A: historical B: social C: Mana Whenua D: knowledge E: technology F: physical attributes G: aesthetic H: context. The values that are evident within scheduled historic heritage places (at the time of scheduling) are identified in the column headed ‘Known heritage values’ in the schedule. Applicability of rules Rules controlling the subdivision, use, and development of land and water within scheduled historic heritage places are set out in the Historic Heritage overlay rules. - Historic Heritage. The rules in the historic heritage overlay activity tables apply to all scheduled historic heritage places. They apply to all land and water within the extent of the scheduled historic heritage place, including the public realm, land covered by water and any body of water. -

Symonds Street Cemetery

Symonds Street Cemetery St Martins Lane Karangahape Road Key Rose Trail Walkway Trail guide for the Jewish, Presbyterian and Catholic areas Symonds Street Informal route Rose Trail 1 A 3 2 A Cemetery entrance 4 1 Feature in trail guide Known grave 23 Labelled tree/plant 24 5 6 Grafton Cycleway/ 22 25 walkway 8 7 9 10 Upper Queen Street Auckland’s oldest public Grafton Bridge cemetery 11 H 12 This trail guide will show you many interesting parts of G 13 the Jewish, Presbyterian and Catholic sections of the Symonds Street Cemetery. F Symonds Street You’ll uncover the stories of many interesting people who were buried here, as well as those of significant 15 14 21 specimen trees and old roses in this part of the cemetery, which is is also an important urban forest.. 16 To walk the trail will take about 30 minutes. Follow the 20 19 red markers. It is the most accessible part of Auckland’s oldest public cemetery. 18 17 I Most of this trail follows formed paths. Please do not walk across the graves. J There are two more self-guided trails on the other side So uth of Symonds Street. The Hobson Walk covers many ern M m important graves in the Anglican and General/Wesleyan a o e to r sectors. Bishop Selwyn’s Path and the Waiparuru Nature rw t a S y u Trail have more detail about Grafton Bridge and the r u r ecology of the forested gully. You can access more a p ai information on our mobile app (see back page). -

Waitematā Local Board Achievements Report 1 July 2015 - 30 June 2016

Waitematā Local Board Achievements Report 1 July 2015 - 30 June 2016 Waitematā Local Board Achievements Report 1July 2015 – 30 June 2016 2 Table of Contents Message from the Chair ............................................................................................. 4 Waitematā Local Board Members .............................................................................. 5 Waitematā Local Board Governance.......................................................................... 6 Official Duties ........................................................................................................... 11 Waitematā – The Economic Hub .............................................................................. 15 Local Engagement…………………………………………………………………………15 Planning for Waitematā……………………………………………………………………18 Local Board Agreement………………………………………………………………18 Seismic Exemplar Guidebook ……………………………………………………….18 Auckland Domain Masterplan………………………………………………………..19 Becoming a Low Carbon Community……………………………………………….20 Newton and Eden Terrace Plan……………………………………………………..21 Major Projects and Initiatives…………………………………………………………......22 Weona-Westmere Coastal Walkway………………………………………………..22 Ellen Melville Centre Upgrade……………………………………………………….23 Myers Park Development…………………………………………………………….24 Newmarket Laneways………………………………………………………………...25 Symonds Street Cemetery…………………………………………………………...25 Low Carbon Initiatives………………………………………………………………...26 Ecological Restoration………………………………………………………………..27 Waipapa Stream Restoration………………………………………………………...28 -

'Each in His Narrow Cell for Ever Laid'

‘Each in his narrow cell for ever laid’: Dunedin’s Southern Cemetery and its New Zealand Counterparts ALEXANDER TRAPEZNIK AND AUSTIN GEE ew Zealand cemeteries,1 in international terms, are unusual in the fact that there are any historic burials or monuments at all. It tends to be only the countries of British and Irish settlement that N 2 burials are left undisturbed in perpetuity. New Zealand follows the practice codified by the British Burial Acts of the 1850s that specified that once buried, ‘human remains could never again be disturbed except by special licence’.3 This reversed the previous practice of re-using graves and became general in the period in which most of New Zealand’s surviving historic cemeteries were established. The concept of each individual being given a single grave or family plot had been established in the early decades of the nineteenth century, following the example of Public History Review Vol 20 (2013): 42-67 ISSN: 1833-4989 © UTSePress and the authors Public History Review | Trapeznik & Gee the hugely influential Père-Lachaise in Paris. In earlier periods, only the graves of the wealthy had been given permanent markers or monuments, as a reader of Gray’s Elegy will know. Family plots are often seen as an expression of the importance given to hereditary property ownership, and this extended further down the social scale into the middle classes in the nineteenth century than it had in previous generations.4 This article will examine in detail a representative example of this new type of cemetery and compare it with its counterparts elsewhere in New Zealand. -

Karangahape Road Streetscape Enhancement Project

Karangahape Road Streetscape Enhancement Project Public feedback received in late February and early March 2016. In late February and early March 2016 the Karangahape Road Streetscape Enhancement Project Team invited feedback from the public to find out what people love about K Road, and how they would make it even better. The project team set up a stall and displays inviting feedback at the Myers Park Medley and White Night events. Members of the public were asked to tell the team (by way of sticky notes on a large map of Karangahape Road) what they love about K Road, and what they would do to make it even better. Additionally, feedback was invited via an online feedback form. In total 368 comments were received, the key themes resulting from this feedback are outlined below. More detailed examples of feedback received and the project team’s responses are provided on the next page. Karangahape Road feedback themes 40.00% 36.41% 35.00% 30.00% 25.54% 25.00% 20.00% 17.66% 15.49% 15.00% 10.00% 8.70% Percentage Percentage of comments feedback in 5.00% 4.08% 3.26% 2.17% 2.17% 1.90% 0.82% 0.00% Theme identified in feedback Theme Sub-theme Number of times Illuminative quotes AT Response Actions for project team mentioned Aesthetics/ Like character of/ culture 70 I love the choices of restaurants and vibrancy, street art One of the project objectives is to reflect and Try to incorporate cultural Environment on K’Rd Always in the process of change - part of the charm complement the unique character and heritage, history and (137 total I love "free spirit" "bohemian" vibe heritage of K-Road. -

Symonds Street Cemetery

Symonds Street Cemetery D Key St Martins Lane Bishop Selwyn’sKarangahape RoadPath Walkway Waiparuru Nature Trail Symonds Street Trail guide for the lower Anglican and General sections, and the Informal route bush of Grafton Gully Bishop Selwyn’s Path Waiparuru Nature Trail E Hobson Walk C 1 Site in this trail guide 14 B Cemetery entrance B 13 Known grave Grafton Cycleway/ walkway Upper Queen Street 12 Grafton Bridge11 View of Grafton Gully with Symonds Street Cemetery on the left, c1840s. John Mitford, Alexander Turnbull Library, 10 Ref: E-216-f-041. 9 F Symonds Street A green heritage trail in the 8 15 central city This trail guide will help you explore the lower part of 7 the Anglican and General/Wesleyan sections of the Symonds Street Cemetery (yellow markers), and the Waiparuru Stream in Grafton Gully (green markers). To walk these trails will take about one hour. You can access these trails by extending Hobson’s Walk (the blue 6 markers, describedSo in a seperate Trail Guide), from either uth side of the Grafton Streete rBridgen or by starting from St m M a Martins Lane. o 16 e to r rw 1 t a S y u The lower paths are steep in places. Make sure you wear r u 2 r appropriate footwear. a p 3 5 ai There is also a trail guide for the Jewish, Presbyterian W and Catholic sections of the cemetery on the other side of Symonds Street – the Rose Trail. You can access more This trail starts at the information on our mobile app (see back page). -

Why Can't I Locate My Ancestor's Place of Burial? the 1882 Cemeteries Act

Why can't I locate my ancestor's place of burial? The 1882 Cemeteries Act and burial details, by David Verran. I have been researching Auckland's Symonds Street and other early Auckland cemeteries since the early 1990s, and, I believe that an understanding of the 1882 Cemeteries Act is crucial when trying to locate the burial places of early New Zealanders. In particular, it was that Act that brought local government into the administration of public cemeteries, which hitherto were largely the preserve of the various denominations represented in New Zealand. Note that while I am talking almost exclusively about New Zealand, some of the general principles may also apply to Australia and Britain/Ireland. Regarding Australia, and in particular early Sydney, I recommend Keith Johnson and Malcolm Sainty’s ‘Sydney burial ground 1819-1901 ... and history of Sydney’s early cemeteries from 1788’ (2001). In November 2004, Stephen Deed presented a Master of Arts Thesis to the University of Otago entitled ‘Unearthly landscapes: the development of the cemetery in nineteenth century New Zealand’. That thesis notes the nineteenth century was “a time of transition for British burial practices, with the traditional churchyard burial ground giving way to the modern cemetery”. Deed noted in his Thesis that Parish churchyard cemeteries had been the pattern in Britain for a thousand years. However, other sources describe private burial grounds as well – in 1835 there were around 14 such burial grounds in London alone. From 1832 (Kensal Green was the first) to 1841, there were seven commercially managed private garden cemeteries established on the then fringe areas of the London metropolitan area, Highgate for example was opened in 1839. -

Karangahape Road Loop

Cafés: Symonds Street, St Kevin's Arcade Public toilets: Myers Park and corner Grafton Bridge Children’s playgrounds: UA-S003 Myers Park Karangahape Road Loop Dogs: On leash only Description: A mix of level paths, steps and slightly inclined paths. Suitable for users of average fitness and mobility. May require boots in wet weather, running shoes suitable in dry Symonds Street Park, Myers Park, and Albert Park weather. To see: Symonds Street Cemetery, St Kevin's Arcade, Myers Park, Khartoum Place, Auckland Art Gallery, Albert Park Nearby Attractions: Auckland Art Gallery, Symonds Street Cemetery with Time: approx. 40 minutes. (about 3.67 kms) historical graves Supported by: www.walksinauckland.co.nz Unleashed Ventures Limited Copyright 2012 Start: Entrance, The University of Auckland, Recreation Centre (Building 314 Symonds Street) 1. Cross Symonds Street at the pedestrian lights towards the Faculty of Engineering 2. Turn right > along Symonds Street heading south 3. At the corner of St Martin’s Lane follow the path into the cemetery that runs parallel to Symonds Street, exit to the right > before the Grafton Bridge OR 4. Optional ** Turn left into St Martin’s lane, then turn next right > into Symonds Street cemetery 5. Take the next left < turn and then follow the path that goes under the Grafton Bridge and back around the outside the cemetery, returning to Symonds Street exit ** 6. Cross over Symonds Street at the Karangahape Road traffic lights, and turn left < along Symonds Street (heading south) 7. Take the second entrance on the right > into Symonds Street Cemetery, continue straight ahead. 8. -

Symonds Street Cemetery•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6

BC3735 Guide to repair and conservation of monuments Symonds Street Cemetery Find out more: phone 09 301 0101 or visit aucklandcouncil.govt.nz 24 September 2019 Contents Foreword •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 The heritage value of monuments in the Symonds Street Cemetery ••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 Monument designs ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 Monument types •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••12 Overview of policies in the Symonds Street Cemetery conservation plan •••••••••••••••••15 Condition of monuments ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••17 What to consider for the conservation of monuments ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••18 Maintenance and condition issues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••23 Useful contacts •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••31 Appendix 1: Process flow chart •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••32 Appendix 2: Memorial information form ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••35 Appendix 3: Proposed monument works form •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••37 3 Foreword The Symonds Street Cemetery is recognised as being of outstanding significance as one of New Zealand’s oldest urban cemeteries. This document relates